CYANOSIS

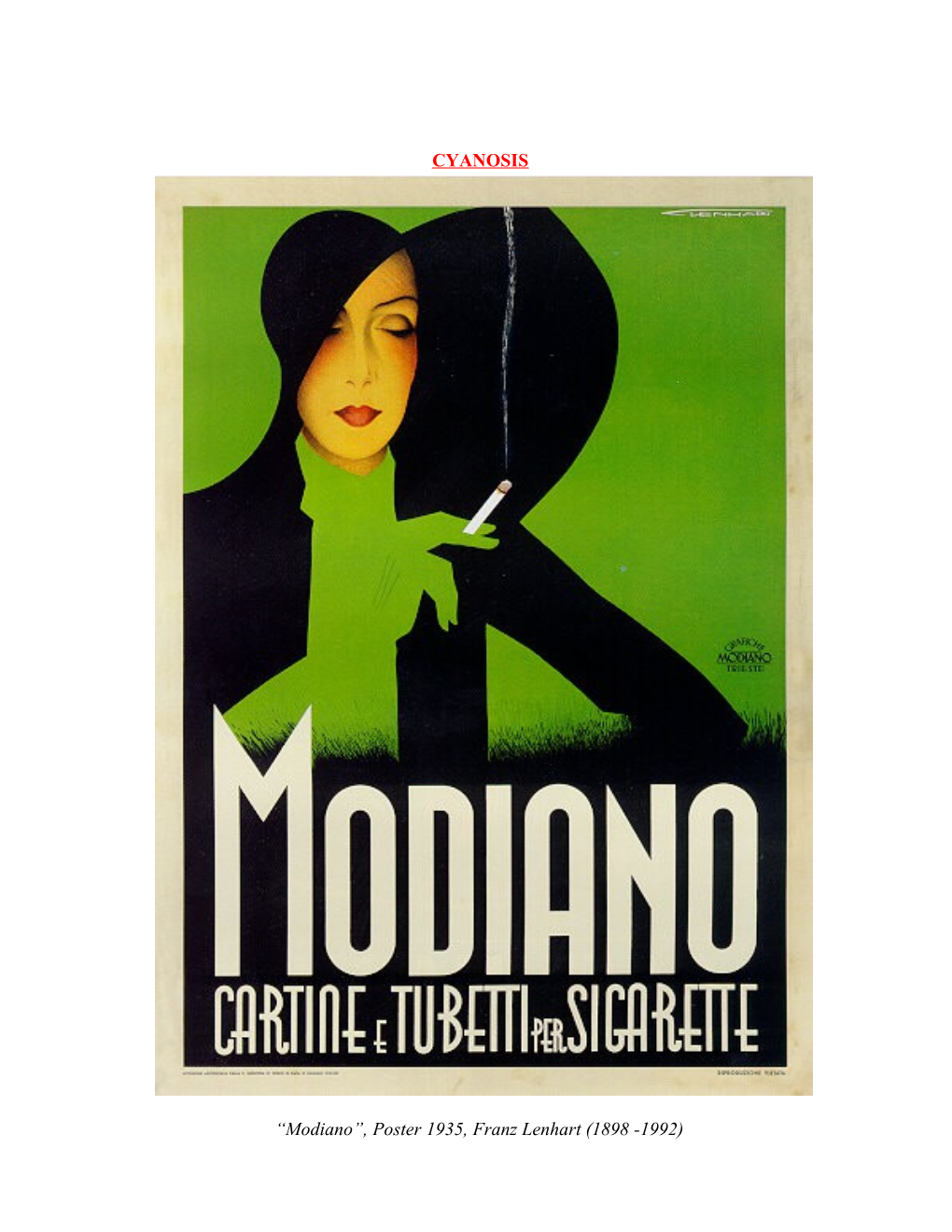

“Modiano”, Poster 1935, Franz Lenhart (1898 -1992) Franz Lenhart’s (admittedly) stunning Art Nouveau poster depicting the once widely held perception of the “sexiness” of smoking. Unfortunately it is now appreciated that the long term consequences of smoking may lead to the distinctly unsexy image of being cyanosed and strapped to a home oxygen unit. Whilst the ruby lipped appearance of Lenhart’s Modiano model will never be regained, a light shade of mauve may yet be possible with modern medical management.

CYANOSIS

Introduction

Cyanosis refers to the clinical sign of bluish discoloration of the skin and/ or mucous membranes due to hypoxia and/ or poor peripheral perfusion.

Cyanosis in a woman with severe hypoxia.

Historically this was used as a key clinical indicator of hypoxia.

This clinical sign was emphasized largely before the era of rapid arterial blood gas analysis and pulse oximetry.

The clinical assessment of hypoxia however is often unreliable and the specific sign of cyanosis is a late sign.

Therefore, although cyanosis is an important clinical observation, its absence does not rule out the possibility of significant hypoxia.

Pathology

At least 5 grams/dL of unoxygenated hemoglobin in the capillaries is required to clinically appreciate cyanosis. Patients who are anemic therefore may be hypoxic without showing any signs of cyanosis.

Further the appearance of hypoxia will also be influenced by: ● The total Hb of the patient:

♥ The lower the value, the more likely cyanosis will be missed

● The oxygen saturation of the blood:

♥ Higher values (eg patient on oxygen) will mask cyanosis

These relationships are demonstrated in the graph below.

Oxygen and hemoglobin values at which central cyanosis occurs: The threshold for central cyanosis is a capillary reduced hemoglobin content of 5 g/dL, which can occur at varying values of the 2 parameters that are measured most commonly, arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2) and arterial hemoglobin content. The vertical axis shows values for venous, capillary, and arterial reduced hemoglobin (RHB, g/dL blood), and the horizontal axis shows a percent saturation of hemoglobin in arterial blood (SaO2) along with corresponding PaO2 (mm Hg). Each diagonal line represents different hemoglobin content (g/dL).

For example, central cyanosis can manifest when SaO2 is 85% in a patient with a hemoglobin of 15 g/dL. Tissue hypoxia:

It is important to recognize that tissue hypoxia is not only caused by reduced partial pressures of oxygen. It may also be due to impaired tissue perfusion or reduced haemoglobin levels.

The total oxygen delivery (or “oxygen flux”) to the tissues is determined by the following equation:

O2 flux = CO x O2 content of the blood.

= Cardiac output x (O2 carrying capacity of Hb + dissolved O2 )

= CO (mls /min) x (1.39 Hb gm / 100 mls x SAT % + 0.3 / 100mls at PaO2 of 100 mmHg)

Cyanosis due to abnormal haemoglobin forms:

Abnormal haemoglobin forms may also cause a cyanotic picture. In these cases the patient may have a normal PaO2 and a relatively normal pulse oximetry reading, yet be severely hypoxic due to the presence of a non-functional haemoglobin.

Examples include:

1. Methemoglobin:

Methemaglobinemia refers to hemoglobin, which contains its iron in the oxidized Fe+++ (ferric) form, as opposed to the normal reduced Fe++ (ferrous) form. Unlike the Fe++ form the Fe+++ form cannot carry oxygen.

Normal adults have levels of methemaglobin of up to 1%.

Levels that are greater than 1% are referred to as methemaglobinemia

Methemoglobin results in an intense bluish tinge to the skin; therefore, giving the appearance of cyanosis. The patient is hypoxic due to the reduced carrying capacity of the affected hemoglobin, rather than a reduced PaO2 level.

See also separate guidelines for methemaglobinemia.

2. Sulfhemoglobinemia:

Sulfhemoglobinemia is a rare condition caused by sulfur binding with hemoglobin.

Sulfhemoglobin like, methemoglobin cannot bind oxygen. Unlike methemoglobin, the iron moiety remains in the reduced state (Hb Fe++).

Like methemoglobinemia, sulfhemoglobinemia causes an intense bluish tinge to the skin and mucous membranes. The patient is hypoxic due to the reduced carrying capacity of the affected hemoglobin, rather than a reduced PaO2 level.

Hypoxia where cyanosis may not be apparent:

1. Carboxyhemoglobin:

This is an abnormal haemoglobin due to the presence of carbon monoxide, COHb.

The patient can be significantly hypoxic, because of the reduced oxygen carrying capacity of their poisoned haemoglobin, and providing PaO2 /SaO2 levels are normal, cyanosis may not be apparent.

See also separate guidelines for carbon monoxide poisoning.

2. Cyanide poisoning:

The patient can have profound tissue hypoxia here without any sign of cyanosis. Their haemoglobin is normally oxygenated, but the tissue cytochromes cannot utilize this oxygen

Differential diagnoses:

Pseudocyanosis is a bluish tinge to the skin and/or mucous membranes that is not caused by tissue hypoxia or poor perfusion.

Causes may include:

Metals, in particular:

● Silver nitrate, silver iodide, silver, lead

Drugs, in particular:

● Phenothiazines, amiodarone, chloroquine hydrochloride

Chemicals:

● Some food coloring agents.

Pseudocyanosis is considered when the patient demonstrates no cardiopulmonary symptoms and the skin does not blanch under pressure. Pulse oximetry or arterial blood gas measurement may be required to confirm the suspicion. Co-oximetry for methemoglobin should also be checked.

Clinical Assessment

Clinical classification of cyanosis:

Cyanosis is generally divided into central or peripheral Central cyanosis:

● Central cyanosis also results in peripheral cyanosis and indicates hypoxia.

Peripheral cyanosis:

● Peripheral cyanosis is a bluish tinge to the periphery (fingers and toes predominantly) and may occur with or without central cyanosis (ie, with or without hypoxemia).

● When unaccompanied by central cyanosis (hypoxemia, as determined by blood gas analysis), peripheral cyanosis is due to poor tissue perfusion, (of whatever causation).

Although cyanosis is an important clinical observation, its absence does not rule out the possibility of significant hypoxia.

Other clinical signs, (though non-specific) will be more important in suggesting the possibility of hypoxia, including:

● Pulse oximeter readings

♥ This is a far more sensitive indicator of hypoxia, than the late clinical sign of cyanosis.

♥ If the cyanosis is due to an abnormal haemoglobin form, (carboxyhemoglobin, methemoglobin, sulfhemoglobin) the pulse oximeter readings will be unreliable.

● Tachycardia

● Tachypnea

● Mental status changes: confusion, agitation.

Note however that if a patient is chronically hypoxic they may not appear to be “unwell”!

Factors making the assessment of cyanosis difficult:

Factors making the detection of cyanosis problematic include:

● Room lighting conditions

● Skin pigmentation

● Nail polish, (peripheral cyanosis)

● The clinical experience and skill of the observer will also be an important factor in the detection of cyanosis. Investigations

The type and extent of investigation undertaken for a patient who presents with cyanosis will depend on the clinical suspicion for the particular underlying pathology on a case by case basis

1. ABGs:

● This will be the most useful investigation, to both confirm the diagnosis of hypoxia, due to a lowered PaO2 and to assess its degree of severity.

● A normal PaO2 however will not rule out significant tissue hypoxia, as this may also be due to perfusion problems or hemoglobin pathology.

2. Co-oximetry:

● Co-oximetry, done on routine blood gas analysis, can directly measure COHb and MetHb levels

Other more specific investigations are done according to the index of clinical suspicion for any condition.

Management

Specific management will obviously depend on:

● How unwell the patient is.

● The underlying pathology.

References

1. From Martin L, Khalil H: How much reduced hemoglobin is necessary to generate central cyanosis? Chest 1990 Jan; 97(1): 182-5.

Dr J. Hayes June 2011.