Prosecutor, cop killer's lawyer make life- and-death arguments By Jose Luis Jiménez STAFF WRITER November 30, 2005

VISTA – The fabric that keeps the community together was ripped by the murder of a young Oceanside police officer and only can be repaired by executing the killer, a prosecutor told a Superior Court jury yesterday.

Acknowledging the crime was "horrible," the murderer's defense attorneys pleaded for leniency, arguing every life is precious and can be redeemed.

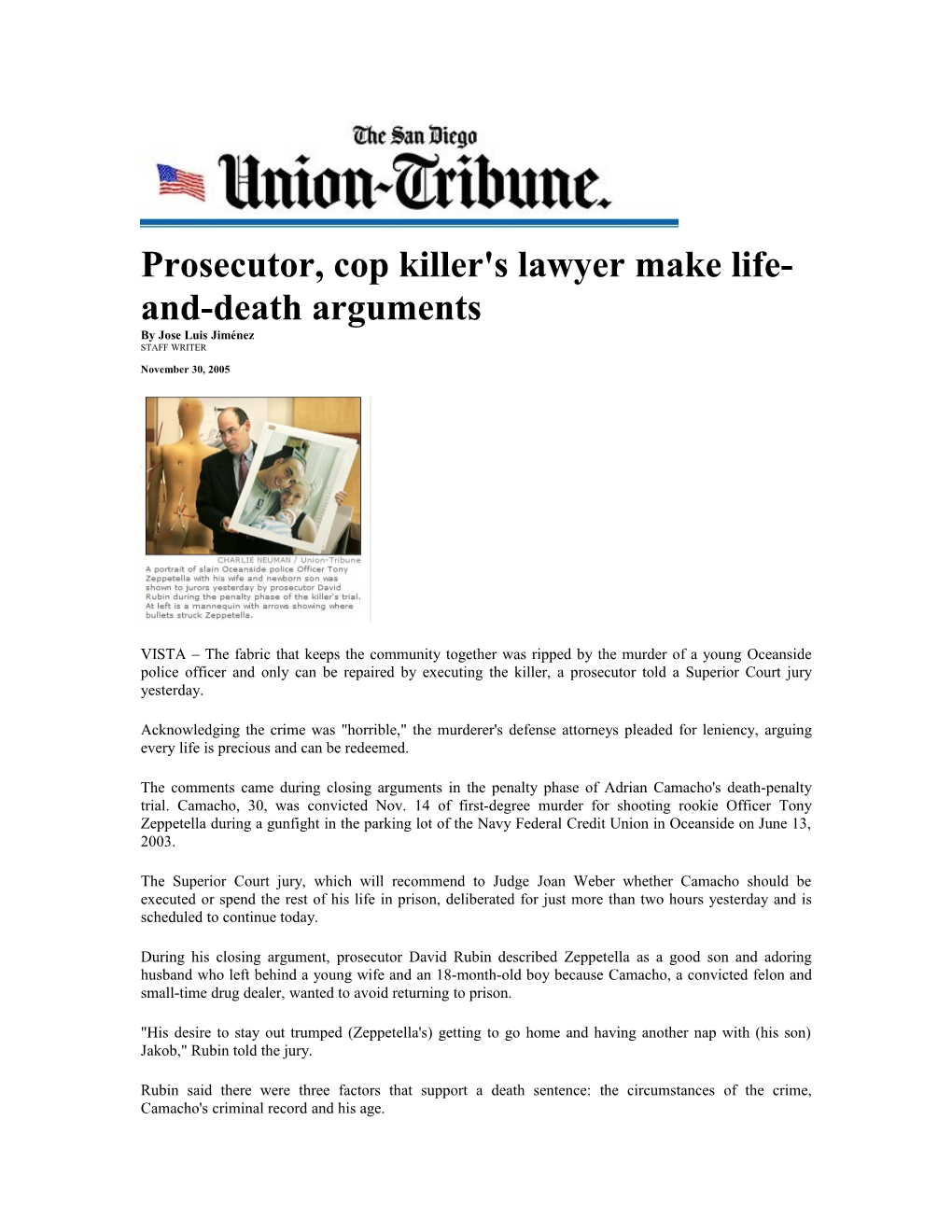

The comments came during closing arguments in the penalty phase of Adrian Camacho's death-penalty trial. Camacho, 30, was convicted Nov. 14 of first-degree murder for shooting rookie Officer Tony Zeppetella during a gunfight in the parking lot of the Navy Federal Credit Union in Oceanside on June 13, 2003.

The Superior Court jury, which will recommend to Judge Joan Weber whether Camacho should be executed or spend the rest of his life in prison, deliberated for just more than two hours yesterday and is scheduled to continue today.

During his closing argument, prosecutor David Rubin described Zeppetella as a good son and adoring husband who left behind a young wife and an 18-month-old boy because Camacho, a convicted felon and small-time drug dealer, wanted to avoid returning to prison.

"His desire to stay out trumped (Zeppetella's) getting to go home and having another nap with (his son) Jakob," Rubin told the jury.

Rubin said there were three factors that support a death sentence: the circumstances of the crime, Camacho's criminal record and his age. As for the crime, Rubin argued that Zeppetella could not know he would be ambushed after stopping Camacho for a traffic violation in the credit union parking lot on College Avenue. Further, Camacho did not just shoot the officer and flee. He shot him 13 times, including once with the officer's gun. A total of 34 rounds were fired by both men.

"Each shot is another decision by (Camacho) to rob and take from this community and those families this lovely young man," Rubin told the jury. "(Camacho) showed no remorse at the crime scene."

Camacho's criminal record contains five felony convictions in a six-year span, starting in 1993 with a charge of possessing methamphetamine to a 1999 conviction for driving recklessly while fleeing a police officer.

Further, Camacho was 28 when he murdered the officer, meaning he was mature enough to understand his actions were wrong, Rubin said.

"(Camacho) wants life. He wants you to grant leniency," Rubin said. "The man who took (Zeppetella) from us, from this community, deserves death."

Deputy Public Defender Kathleen Cannon, assisted by her colleague William Stone, showed the jury a pyramid topped by the death penalty. Cannon argued that executions should be reserved for only the worst criminals such as terrorists and men who snatch little girls from their bedrooms in the middle of the night.

Cannon said there were seven factors the jury could point to and send Camacho to prison for the rest of his life, where every day he would think about what he has lost.

The factors ranged from Camacho being impaired because of a mental disease or intoxication to suffering from extreme mental disease or emotional disturbance. Jurors also could offer Camacho mercy and leniency, she said.

Cannon said her client did not leave the house that morning looking to kill a police officer. He went to a North County neighborhood to deal drugs and was on his way home when he was spotted by Zeppetella, she said. At the time he was either high on methamphetamine or suffering from withdrawals when, in an instant, he decided to shoot the officer, Cannon said.

Afterward, he fled to his mother-in-law's home in Oceanside, where he tried to commit suicide and scrawled the words "I'm sorry" in his own blood on the bathroom wall. His actions at the home showed remorse and guilt, Cannon said.

"Morally, he couldn't live with it," Cannon said. "Morally, he was not the worst of the worst."

She said Camacho, who has a son and a daughter, struggled with his addiction to methamphetamine and heroin. He could have abandoned his family for a life of getting high on the streets, but instead struggled to beat the habit by going into drug rehabilitation and working construction jobs to support his family. As for his criminal record, they were for nonviolent crimes, the defense attorney said.

"This is about heart. This is about the preciousness of life," Cannon said. "It's not about vengeance or an eye for an eye."

The lawyer ended by singing the first verse of the song "Amazing Grace."