Final Report for a Robotic Exploration Mission to Mars and Phobos Argos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phobos, Deimos: Formation and Evolution Alex Soumbatov-Gur

Phobos, Deimos: Formation and Evolution Alex Soumbatov-Gur To cite this version: Alex Soumbatov-Gur. Phobos, Deimos: Formation and Evolution. [Research Report] Karpov institute of physical chemistry. 2019. hal-02147461 HAL Id: hal-02147461 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02147461 Submitted on 4 Jun 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Phobos, Deimos: Formation and Evolution Alex Soumbatov-Gur The moons are confirmed to be ejected parts of Mars’ crust. After explosive throwing out as cone-like rocks they plastically evolved with density decays and materials transformations. Their expansion evolutions were accompanied by global ruptures and small scale rock ejections with concurrent crater formations. The scenario reconciles orbital and physical parameters of the moons. It coherently explains dozens of their properties including spectra, appearances, size differences, crater locations, fracture symmetries, orbits, evolution trends, geologic activity, Phobos’ grooves, mechanism of their origin, etc. The ejective approach is also discussed in the context of observational data on near-Earth asteroids, main belt asteroids Steins, Vesta, and Mars. The approach incorporates known fission mechanism of formation of miniature asteroids, logically accounts for its outliers, and naturally explains formations of small celestial bodies of various sizes. -

Mars Exploration: an Overview of Indian and International Mars Missions Nayamavalsa Scariah1, Dr

Taurian Innovative Journal/Volume 1/ Issue 1 Mars exploration: An overview of Indian and International Mars Missions NayamaValsa Scariah1, Dr. Mili Ghosh2, Dr.A.P.Krishna3 Birla Institute of Technology, Mesra, Ranchi Abstract- Mars is the fourth planet from the sun. It is 1. Introduction also known as red planet because of its iron oxide content. There are lots of missions have been launched to Mars is also known as red planet, because of the mars for better understanding of our neighboring planet. reddish iron oxide prevalent on its surface gives it a There are lots of unmanned spacecraft including reddish appearance. It is the fourth planet from sun. orbiters, landers and rovers have been launched into mars since early 1960. Sputnik was the first satellite The term sol is used to define duration of solar day on launched in 1957 by Soviet Union. After seven failure Mars. A mean Martian solar day or sol is 24 hours 39 missions to Mars, Mariner 4 was the first satellite which minutes and 34.244 seconds. Many space missions to reached the Martian orbiter successfully. The Viking 1 Mars have been planned and launched for Mars was the first lander reached on Mars on 1975. India exploration (Table:1) but most of them failed without successfully launched a spacecraft, Mangalyan (Mars completing the task specially in early attempts th Orbiter Mission) on 5 November, 2013, with five whereas some NASA missions were very payloads to Mars. India was the first nation to successful(such as the twin Mars Exploration Rovers, successfully reach Mars on its first attempt. -

25 Years of Indian Remote Sensing Satellite (IRS)

2525 YearsYears ofof IndianIndian RemoteRemote SensingSensing SatelliteSatellite (IRS)(IRS) SeriesSeries Vinay K Dadhwal Director National Remote Sensing Centre (NRSC), ISRO Hyderabad, INDIA 50 th Session of Scientific & Technical Subcommittee of COPUOS, 11-22 Feb., 2013, Vienna The Beginning • 1962 : Indian National Committee on Space Research (INCOSPAR), at PRL, Ahmedabad • 1963 : First Sounding Rocket launch from Thumba (Nov 21, 1963) • 1967 : Experimental Satellite Communication Earth Station (ESCES) established at Ahmedabad • 1969 : Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) established (15 August) PrePre IRSIRS --1A1A SatellitesSatellites • ARYABHATTA, first Indian satellite launched in April 1975 • Ten satellites before IRS-1A (7 for EO; 2 Met) • 5 Procured & 5 SLV / ASLV launch SAMIR : 3 band MW Radiometer SROSS : Stretched Rohini Series Satellite IndianIndian RemoteRemote SensingSensing SatelliteSatellite (IRS)(IRS) –– 1A1A • First Operational EO Application satellite, built in India, launch USSR • Carried 4-band multispectral camera (3 nos), 72m & 36m resolution Satellite Launch: March 17, 1988 Baikanur Cosmodrome Kazakhstan SinceSince IRSIRS --1A1A • Established of operational EO activities for – EO data acquisition, processing & archival – Applications & institutionalization – Public services in resource & disaster management – PSLV Launch Program to support EO missions – International partnership, cooperation & global data sets EarlyEarly IRSIRS MultispectralMultispectral SensorsSensors • 1st Generation : IRS-1A, IRS-1B • -

The Space-Based Global Observing System in 2010 (GOS-2010)

WMO Space Programme SP-7 The Space-based Global Observing For more information, please contact: System in 2010 (GOS-2010) World Meteorological Organization 7 bis, avenue de la Paix – P.O. Box 2300 – CH 1211 Geneva 2 – Switzerland www.wmo.int WMO Space Programme Office Tel.: +41 (0) 22 730 85 19 – Fax: +41 (0) 22 730 84 74 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.wmo.int/pages/prog/sat/ WMO-TD No. 1513 WMO Space Programme SP-7 The Space-based Global Observing System in 2010 (GOS-2010) WMO/TD-No. 1513 2010 © World Meteorological Organization, 2010 The right of publication in print, electronic and any other form and in any language is reserved by WMO. Short extracts from WMO publications may be reproduced without authorization, provided that the complete source is clearly indicated. Editorial correspondence and requests to publish, reproduce or translate these publication in part or in whole should be addressed to: Chairperson, Publications Board World Meteorological Organization (WMO) 7 bis, avenue de la Paix Tel.: +41 (0)22 730 84 03 P.O. Box No. 2300 Fax: +41 (0)22 730 80 40 CH-1211 Geneva 2, Switzerland E-mail: [email protected] FOREWORD The launching of the world's first artificial satellite on 4 October 1957 ushered a new era of unprecedented scientific and technological achievements. And it was indeed a fortunate coincidence that the ninth session of the WMO Executive Committee – known today as the WMO Executive Council (EC) – was in progress precisely at this moment, for the EC members were very quick to realize that satellite technology held the promise to expand the volume of meteorological data and to fill the notable gaps where land-based observations were not readily available. -

Design of the Wavefront Sensor Unit of ARGOS, the LBT Laser Guide Star System

UNIVERSITA` DEGLI STUDI DI FIRENZE Dipartimento di Fisica e Astronomia Scuola di Dottorato in Astronomia Ciclo XXIV - FIS05 Design of the wavefront sensor unit of ARGOS, the LBT laser guide star system Candidato: Marco Bonaglia arXiv:1203.5081v1 [astro-ph.IM] 22 Mar 2012 Tutore: Prof. Alberto Righini Cotutore: Dott. Simone Esposito A common use for a glass plate is as a beam splitter, tilted at an angle of 45◦ [:::] Since this can severely degrade the image, such plate beam splitters are not recommended in convergent or divergent beams. W. J. Smith, Modern Optical Engineering. Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 The Large Binocular Telescope . 2 1.2 LUCI . 4 1.3 First Light AO system . 5 1.3.1 Angular anisoplanatism . 8 1.4 Wide field AO correction . 9 1.5 Laser guide star AO . 10 1.5.1 Limits of LGS AO . 11 1.5.2 Rayleigh LGS . 13 1.6 LGS-GLAO facilities . 14 1.6.1 GLAS . 15 1.6.2 The MMT GLAO system . 15 1.6.3 SAM . 18 2 ARGOS: a laser guide star AO system for the LBT 21 2.1 System design . 22 2.2 Study of ARGOS performance . 29 2.2.1 The simulation code . 30 2.2.2 Results of ARGOS end-to-end simulations . 36 3 The wavefront sensor dichroic 43 3.1 Effects of a window in a convergent beam . 43 3.2 Aberration compensation with window shape . 47 3.2.1 Effects of a wedge between surfaces . 48 3.2.2 Effects of a cylindrical surface . -

Mars Exploration - a Story Fifty Years Long Giuseppe Pezzella and Antonio Viviani

Chapter Introductory Chapter: Mars Exploration - A Story Fifty Years Long Giuseppe Pezzella and Antonio Viviani 1. Introduction Mars has been a goal of exploration programs of the most important space agencies all over the world for decades. It is, in fact, the most investigated celestial body of the Solar System. Mars robotic exploration began in the 1960s of the twentieth century by means of several space probes sent by the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR). In the recent past, also European, Japanese, and Indian spacecrafts reached Mars; while other countries, such as China and the United Arab Emirates, aim to send spacecraft toward the red planet in the next future. 1.1 Exploration aims The high number of mission explorations to Mars clearly points out the impor- tance of Mars within the Solar System. Thus, the question is: “Why this great interest in Mars exploration?” The interest in Mars is due to several practical, scientific, and strategic reasons. In the practical sense, Mars is the most accessible planet in the Solar System [1]. It is the second closest planet to Earth, besides Venus, averaging about 360 million kilometers apart between the furthest and closest points in its orbit. Earth and Mars feature great similarities. For instance, both planets rotate on an axis with quite the same rotation velocity and tilt angle. The length of a day on Earth is 24 h, while slightly longer on Mars at 24 h and 37 min. The tilt of Earth axis is 23.5 deg, and Mars tilts slightly more at 25.2 deg [2]. -

+ Return to Flight Implementation Plan -- 12Th Edition (8.4 Mb PDF)

NASA’s Implementation Plan for Space Shuttle Return to Flight and Beyond A periodically updated document demonstrating our progress toward safe return to flight and implementation of the Columbia Accident Investigation Board recommendations June 20, 2006 Volume 1, Twelfth Edition An electronic version of this implementation plan is available at www.nasa.gov NASA’s Implementation Plan for Space Shuttle Return to Flight and Beyond June 20, 2006 Twelfth Edition Change June 20, 2006 This 12th revision to NASA’s Implementation Plan for Space Shuttle Return to Flight and Beyond provides updates to three Columbia Accident Investigation Board Recommendations that were not fully closed by the Return to Flight Task Group, R3.2-1 External Tank (ET), R6.4-1 Thermal Protection System (TPS) On-Orbit Inspection and Repair, and R3.3-2 Orbiter Hardening and TPS Impact Tolerance. These updates reflect the latest status of work being done in preparation for the STS-121 mission. Following is a list of sections updated by this revision: Message from Dr. Michael Griffin Message from Mr. William Gerstenmaier Part 1 – NASA’s Response to the Columbia Accident Investigation Board’s Recommendations 3.2-1 External Tank Thermal Protection System Modifications (RTF) 3.3-2 Orbiter Hardening (RTF) 6.4-1 Thermal Protection System On-Orbit Inspect and Repair (RTF) Remove Pages Replace with Pages Cover (Feb 17, 2006) Cover (Jun. 20, 2006 ) Title page (Feb 17, 2006) Title page (Jun. 20, 2006) Message From Michael D. Griffin Message From Michael D. Griffin (Feb 17, 2006) -

Getting to Mars How Close Is Mars?

Getting to Mars How close is Mars? Exploring Mars 1960-2004 Of 42 probes launched: 9 crashed on launch or failed to leave Earth orbit 4 failed en route to Mars 4 failed to stop at Mars 1 failed on entering Mars orbit 1 orbiter crashed on Mars 6 landers crashed on Mars 3 flyby missions succeeded 9 orbiters succeeded 4 landers succeeded 1 lander en route Score so far: Earthlings 16, Martians 25, 1 in play Mars Express Mars Exploration Rover Mars Exploration Rover Mars Exploration Rover 1: Meridiani (Opportunity) 2: Gusev (Spirit) 3: Isidis (Beagle-2) 4: Mars Polar Lander Launch Window 21: Jun-Jul 2003 Mars Express 2003 Jun 2 In Mars orbit Dec 25 Beagle 2 Lander 2003 Jun 2 Crashed at Isidis Dec 25 Spirit/ Rover A 2003 Jun 10 Landed at Gusev Jan 4 Opportunity/ Rover B 2003 Jul 8 Heading to Meridiani on Sunday Launch Window 1: Oct 1960 1M No. 1 1960 Oct 10 Rocket crashed in Siberia 1M No. 2 1960 Oct 14 Rocket crashed in Kazakhstan Launch Window 2: October-November 1962 2MV-4 No. 1 1962 Oct 24 Rocket blew up in parking orbit during Cuban Missile Crisis 2MV-4 No. 2 "Mars-1" 1962 Nov 1 Lost attitude control - Missed Mars by 200000 km 2MV-3 No. 1 1962 Nov 4 Rocket failed to restart in parking orbit The Mars-1 probe Launch Window 3: November 1964 Mariner 3 1964 Nov 5 Failed after launch, nose cone failed to separate Mariner 4 1964 Nov 28 SUCCESS, flyby in Jul 1965 3MV-4 No. -

Mars Insight Launch Press Kit

Introduction National Aeronautics and Space Administration Mars InSight Launch Press Kit MAY 2018 www.nasa.gov 1 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents Introduction 4 Media Services 8 Quick Facts: Launch Facts 12 Quick Facts: Mars at a Glance 16 Mission: Overview 18 Mission: Spacecraft 30 Mission: Science 40 Mission: Landing Site 53 Program & Project Management 55 Appendix: Mars Cube One Tech Demo 56 Appendix: Gallery 60 Appendix: Science Objectives, Quantified 62 Appendix: Historical Mars Missions 63 Appendix: NASA’s Discovery Program 65 3 Introduction Mars InSight Launch Press Kit Introduction NASA’s next mission to Mars -- InSight -- will launch from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California as early as May 5, 2018. It is expected to land on the Red Planet on Nov. 26, 2018. InSight is a mission to Mars, but it is more than a Mars mission. It will help scientists understand the formation and early evolution of all rocky planets, including Earth. A technology demonstration called Mars Cube One (MarCO) will share the launch with InSight and fly separately to Mars. Six Ways InSight Is Different NASA has a long and successful track record at Mars. Since 1965, it has flown by, orbited, landed and roved across the surface of the Red Planet. None of that has been easy. Only about 40 percent of the missions ever sent to Mars by any space agency have been successful. The planet’s thin atmosphere makes landing a challenge; its extreme temperature swings make it difficult to operate on the surface. But if a spacecraft survives the trip, there’s a bounty of science to be collected. -

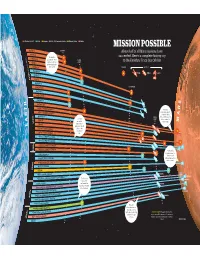

MISSION POSSIBLE KORABL 4 LAUNCH About Half of All Mars Missions Have

Russia/U.S.S.R. U.S. Japan U.K./ESA member states Russia/China India MISSION POSSIBLE KORABL 4 LAUNCH About half of all Mars missions have KORABL 5 ) The frst U.S. succeeded. Here’s a complete history, up s KORAB e L 11 to Mars t spacecraft EARTH a to the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter d mysteriously lost ORBIT MARS 1 h power eight hours c n KORA after launch u BL 13 FAILURE SUCCESS a L ( MARINER 3 s Flyby Orbiter Lander 0 MA 6 RINER 4 9 1 ZOND 2 MARINER 6 IN TRANSIT MARS 1969A MARINER 7 MARS 1969B MARINER 8 S H KOSMOS 419 MA R T RS 2 ORBITER/LANDER The frst man-made object MARS 3 ORBITER/LAN DER A R to land on Mars. s MARINER 9 MARS But contact was lost 0 The frst 7 ORBIT 20 seconds after A MARS 9 4 successful touchdown M 1 Mars surface MARS 5 E exploration found all elements MARS 6 FLYBY/LAND ER essential to MARS 7 FLYBY/LANDER life VIKING 1 ORBITER/LANDER VIKING 2 ORBITER/LANDER s 0 PHOBOS 1 ORBITER/LANDER 8 9 PHOBOS 2 ORBITER/LANDER 1 Pathfinder’s Sojourner was the MARS OBSERVER frst wheeled MARS GLOBAL SURVEYOR vehicle deployed on another planet s MARS 96 ORBITER/LANDER 0 9 MARS PATHFINDER 9 1 NOZOMI MARS CLIMATE ORBITER ONGOING ONGOING 2 PROBES/MARS POLAR LANDER The Phoenix ONGOING DEEP SPACE ONGOING lander frst MARS ODYSSEY confrmed the ONGOING presence of water /BEAGLE 2 LANDER MARS EXPRESS ORBITER in soil samples s RIT MARS EXPLORATION ROVER–SPI ONGOING 0 0 OVER–OPPORTUNITY 0 MARS EXPLORATION R ONGOING 2 ITER MARS RECONNAISSANCE ORB ENIX MARS LANDER PHO Curiosity descended on the -GRUNT/YINGHUO-1 PHOBOS frst “sky crane,” a s B/CURIOSITY highly precise landing DID YOU KNOW? The early missions had 0 MARS SCIENCE LA 1 system for large up to seven diferent names. -

Fusion of Wildlife Tracking and Satellite Geomagnetic Data for the Study of Animal Migration Fernando Benitez-Paez1,2 , Vanessa Da Silva Brum-Bastos1 , Ciarán D

Benitez-Paez et al. Movement Ecology (2021) 9:31 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40462-021-00268-4 METHODOLOGY ARTICLE Open Access Fusion of wildlife tracking and satellite geomagnetic data for the study of animal migration Fernando Benitez-Paez1,2 , Vanessa da Silva Brum-Bastos1 , Ciarán D. Beggan3 , Jed A. Long1,4 and Urška Demšar1* Abstract Background: Migratory animals use information from the Earth’s magnetic field on their journeys. Geomagnetic navigation has been observed across many taxa, but how animals use geomagnetic information to find their way is still relatively unknown. Most migration studies use a static representation of geomagnetic field and do not consider its temporal variation. However, short-term temporal perturbations may affect how animals respond - to understand this phenomenon, we need to obtain fine resolution accurate geomagnetic measurements at the location and time of the animal. Satellite geomagnetic measurements provide a potential to create such accurate measurements, yet have not been used yet for exploration of animal migration. Methods: We develop a new tool for data fusion of satellite geomagnetic data (from the European Space Agency’s Swarm constellation) with animal tracking data using a spatio-temporal interpolation approach. We assess accuracy of the fusion through a comparison with calibrated terrestrial measurements from the International Real-time Magnetic Observatory Network (INTERMAGNET). We fit a generalized linear model (GLM) to assess how the absolute error of annotated geomagnetic intensity varies with interpolation parameters and with the local geomagnetic disturbance. Results: We find that the average absolute error of intensity is − 21.6 nT (95% CI [− 22.26555, − 20.96664]), which is at the lower range of the intensity that animals can sense. -

Spacecraft Navigation Using X-Ray Pulsars

JOURNAL OF GUIDANCE,CONTROL, AND DYNAMICS Vol. 29, No. 1, January–February 2006 Spacecraft Navigation Using X-Ray Pulsars Suneel I. Sheikh∗ and Darryll J. Pines† University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland 20742 and Paul S. Ray,‡ Kent S. Wood,§ Michael N. Lovellette,¶ and Michael T. Wolff∗∗ U.S. Naval Research Laboratory, Washington, D.C. 20375 The feasibility of determining spacecraft time and position using x-ray pulsars is explored. Pulsars are rapidly rotating neutron stars that generate pulsed electromagnetic radiation. A detailed analysis of eight x-ray pulsars is presented to quantify expected spacecraft position accuracy based on described pulsar properties, detector parameters, and pulsar observation times. In addition, a time transformation equation is developed to provide comparisons of measured and predicted pulse time of arrival for accurate time and position determination. This model is used in a new pulsar navigation approach that provides corrections to estimated spacecraft position. This approach is evaluated using recorded flight data obtained from the unconventional stellar aspect x-ray timing experiment. Results from these data provide first demonstration of position determination using the Crab pulsar. Introduction sources, including neutron stars, that provide stable, predictable, and HROUGHOUT history, celestial sources have been utilized unique signatures, may provide new answers to navigating through- T for vehicle navigation. Many ships have successfully sailed out the solar system and beyond. the Earth’s oceans using only these celestial aides. Additionally, ve- This paper describes the utilization of pulsar sources, specifically hicles operating in the space environment may make use of celestial those emitting in the x-ray band, as navigation aides for spacecraft.