Download the Large Pdf File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dolly Parton's Imagination Library

Dolly Parton’s Imagination Library: Children & Youth Partnership for Dare County Frequently Asked Questions How do I register my child for Imagination Library? In order to sign your child up to receive books from Imagination Library, you must complete the registration form which is located on the back of the Imagination Library brochures. You can find these Imagination Library brochures at Dare County Libraries, Surf Pediatrics & Medicine, the Dare County Department of Public Health, or Children & Youth Partnership. You can also contact Carla Heppert at (252)441-0614 or [email protected] to receive a brochure by mail. Can I sign up online? At this time, we do not accept online registrations for Imagination Library. How much does it cost to sign up? Imagination Library books are completely FREE to enrolled children ages birth-5, although donations are always welcomed. How do I donate to Dolly Parton’s Imagination Library in Dare County? In Dare County, Dolly Parton’s Imagination Library is entirely funded by our generous community, through business, organization, and individual donations. It only costs $27 to support a child for a year in Dolly Parton’s Imagination Library, and anyone can donate! Donations can be made payable to Children & Youth Partnership for Dare County (Memo: Imagination Library) and sent to: Children & Youth Partnership for Dare County 534 Ananias Dare Street Manteo, NC 27954 You can also contact Carla Heppert at [email protected] or call (252) 441-0614 to receive a donor envelope by mail or visit www.darekids.org/donate to support the program via an online donation. -

Letter from the Mayor Our Hometown in the Smokies! - Mayor Bryan Atchley

Letter from the Mayor Our hometown in the Smokies! - Mayor Bryan Atchley What a truly exciting time to live and work in Sevierville! Over the past several years, our City has continued to grow in leaps and bounds. Being a life-long native of Sevierville, I have watched this city evolve from a quiet mountain town into a tourist destination and bustling county seat. Still, Sevierville has remained home to some of the warmest, friendliest people in Tennessee and the Southeast. My enthusiasm for Sevierville is most sincere and is a natural way of life for those of us fortunate enough to call this place home. Mayor Bryan Atchley The growth of Sevierville shows positive indicators for a city of its size. This progressive way of thinking and the desire for growth, not only from the city officials but also from the citizens I have been elected to represent, is what gives Sevierville its strength. The city is blessed with solid and forward-thinking leaders who are dedicated to improving our standard of living and maintaining our strong heritage. Operating as the county seat for Sevier County, Sevierville has developed as a diverse business community and serves as the area’s hub for banking and legal services. This diversity has provided Sevierville with a strong and stable economy built around industry, retail and professional services. The downtown area, home to many professional businesses, will be undergoing a facelift and will benefit from the planned development of a large parking facility and trolley system hub in the near future. Tourism in the area promises the most explosive growth. -

For Immediate Release We Are Family Foundation® To

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE WE ARE FAMILY FOUNDATION® TO HONOR DOLLY PARTON AND JEAN PAUL GAULTIER AT 2019 CELEBRATION New York, NY (September 9, 2019) – We Are Family FouNdatioN® (WAFF) will honor legendary artist Dolly Parton and iconic fashion designer Jean Paul Gaultier at its 2019 Celebration on Tuesday, November 5, 2019 at the Hammerstein Ballroom in New York City. WAFF, a not-for-profit organization founded by legendary multiple GRAMMY® Award winning musician Nile Rodgers, is dedicated to the vision of a global family. WAFF creates and supports programs that promote cultural diversity while nurturing the vision, talents and ideas of young people who are positively changing the world. “We’ve wanted to recognize and honor the extraordinary accomplishments of Dolly Parton for many years. Her exemplary work as an artist, businesswoman and philanthropist is an example for us all. She symbolizes everything that is great about music and America. Jean Paul Gaultier is someone who I’m happy to call a friend. His incomparable work as an iconic fashion designer and forward thinker has changed our culture in a way the world has greatly benefitted from. We are enormously grateful to our honorees for their exceptional work to improve humanity and we warmly welcome them into our WAFF family”, said Rodgers. Dolly Parton, legendary singer, songwriter, multi-instrumentalist, record producer, actress, author, businesswoman and humanitarian will receive the Mattie J.T. StepaNek Peacemaker Award. Over the years, Parton has supported many charitable efforts, particularly in the area of literacy, primarily through the Dollywood Foundation. Her literacy program, Dolly Parton's Imagination Library, a part of the Dollywood Foundation, mails one book per month to each enrolled child from the time of their birth until they enter kindergarten. -

'Dolly Celebrates 25 Years of Dollywood' Talent Bios

‘DOLLY CELEBRATES 25 YEARS OF DOLLYWOOD’ TALENT BIOS DOLLY PARTON - "I've always been a writer. My songs are the door to every dream I've ever had and every success I've ever achieved," says Dolly Parton of her incredible career, which has spanned nearly five decades and is showing no signs of slowing down. An internationally renowned superstar, the iconic and irrepressible Parton has contributed countless treasures to the world of music entertainment, penning classic songs such as "Jolene," "Coat of Many Colors," and her mega-hit "I Will Always Love You." With 1977's crossover hit "Here You Come Again," she successfully erased the line between country and pop music without noticeably altering either her music or her image. "I'm not leaving country," she said at the time, "I'm just taking it with me." Making her film debut in the 1980 hit comedy “9 to 5,” Parton earned rave reviews for her performance and an Oscar nomination for writing the title tune, along with her second and third Grammy Awards. Roles in “Steel Magnolias,” “Best Little Whorehouse in Texas,” “Rhinestone,” and “Straight Talk” followed, along with two network television series, made for television movies, network and HBO specials, and guest-starring roles in series television. In 2006, Parton earned her second Oscar nomination for "Travelin' Thru," which she wrote for the film “Transamerica.” Dolly Parton's remarkable life began very humbly. Born January 19, 1946 on a farm in Sevier County, Tennessee, Parton is the fourth of twelve children. Her parents, Robert Lee and Avie Lee Parton struggled to make ends meet in the impoverished East Tennessee hills. -

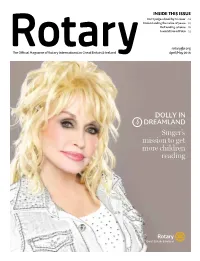

Full Digital Edition

INSIDE THIS ISSUE Don’t judge a book by its cover 04 Understanding the value of peace 20 Befriending scheme 26 A world free of Polio 32 rotarygbi.org The Official Magazine of Rotary International in Great Britain & Ireland April/May 2018 DOLLY IN 4 DREAMLAND Singer’s mission to get more children reading 4 ADVERT 8 12 4 38 36 CONTENTS REGULARS ROTARY IN ACTION GLOBAL IMPACT Rotary in Great Britain Rotary Innovation 12 Dolly Parton 4 & Ireland President 6 Tree Planting Challenge 14 Peace Conference 8 Talk from the Top Rotary Grand Tour 22 Peace Fellows 20 Rotary International President 14 Community Project 24 National Immunisation Day 30 Letters to the Editor 16 RAF Fellowship 26 Michel Zaffran 32 The Rotary Foundation Trustee Chair 22 Rotaract 50th Birthday 36 RI Director 28 Champions of Change 38 It's Gone Viral 34 People of Action 40 And Finally… 50 RAF Fellowship 26 w Get in touch Follo us Enjoy Rotary anywhere Rotary in Great Britain & Ireland Kinwarton Road, Alcester, Warwickshire B49 6PB t: 01789 765 411 rotarygbi.org Editor: Dave King e: [email protected] Look for us online at PR Officer:e: [email protected] rotarygbi.org or follow us: Designer: Martin Tandy e: [email protected] Facebook: /RotaryinGBI The Official Magazine of Rotary International in Great Britain & Ireland Advertising: Media Shed (Agent for Rotary) Twitter: @RotaryGBI Contact: Dawn Tucker, Sales Manager YouTube: Rotary International t: 020 3475 6815 e: [email protected] in Great Britain & Ireland Published by Contently Limited: contentlylondon.co.uk rotarygbi.org ROTARY // 3 ROTARY IN ACTION Imagination Library LUKE ADDISON Don’t judge a book by its cover ITH her tell-tale looks icon of country music has supported something good for kids, it would be to and sweet, sultry voice, many charities through her Dollywood make sure they could read. -

The Library That Dolly Built

DOLLYWOOD AND ABRAMORAMA IN ASSOCIATION WITH THE DOLLYWOOD FOUNDATION PARTNER ON THEATRICAL RELEASE OF THE LIBRARY THAT DOLLY BUILT One-night nationwide event in 325+ theaters on April 2, 2020 New York, NY, Pigeon Forge, TN – March 4, 2020 – Dollywood and Abramorama in association with The Dollywood Foundation have partnered to release THE LIBRARY THAT DOLLY BUILT, a behind-the-scenes look at Dolly Parton’s literacy-focused non-profit, Imagination Library. The one-night event will be integrated with Imagination Library affiliate partners in multiple communities around the country and is set for screenings in over 325+ locations on Thursday, April 2, 2020. Dolly Parton created the Imagination Library to inspire a love for books and reading amongst the nation’s preschool children. Since inception in 1995, the Imagination Library has gifted more than 135 million books to children and is currently gifting books to 1.45 million children around the world each month. The Imagination Library affiliates screening the film will receive 50% of box office proceeds to further their year-round efforts. Dolly Parton said, “I always felt we owed the world a better and deeper understanding of the Imagination Library but the stars never quite aligned. When Nick Geidner came to us with his unique vision and talent, I knew the time had come to make this film. I am a charter member of the Dream More Club so with the help of Abramorama, Dollywood and all of our community partners, we hope to make a big splash in theaters all across the country on April 2. -

Micah Stephens Anthony ART 499 May 1, 2016 Dollywood Or Bust: a Theme Park and Its Community Dollywood Is a Theme-Park Set in T

Micah Stephens Anthony ART 499 May 1, 2016 Dollywood or Bust: A Theme Park and its Community Dollywood is a theme-park set in the mountains of East Tennessee. Located in Sevier County, Tennessee, Dollywood is right next door to Smoky Mountain National Park and is one of the most visited attractions in the state of Tennessee. Dollywood has grown an industry of tourism around Sevier County, specifically on the Pigeon Forge strip, that has made a huge impact on the community. While there are differing opinions on what tourism does to a community, the economy that it builds in this particular area allows the community to sustain itself. Dolly Parton, the namesake and figure head of the park, has often said of herself, “It takes a lot of money to look this cheap” (N.p.). Similarly, some say that the tourism on the strip looks cheap, but it takes substantial funding to support a community sustained by tourism. While Dollywood’s opening season was in 1986, the park has a history dating back to 1961. Dollywood as we know it now has taken many different names through the years, beginning in 1961 as Rebel Railroad. Rebel Railroad, owned and operated by the Robins Brothers opened for its first season in 1961(“Historic Attractions”). The park focused on local heritage with a coal fired steam train and saloon, but didn’t have many other attractions at this stage in its development. It had a successful opening season and continued with its success until 1970. The park was bought by then owner of the NFL’s Cleveland Browns, Art Modell, in 1970. -

Page 223 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION § 403K

Page 223 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION § 403k National Forest, located within and adjacent to State of Tennessee of legislative jurisdiction the right-of-way for section 8A of the Foothills over the lands and notification of such accept- Parkway between Tennessee Highway Numbered ance being given to the Secretary of the Inte- 32 and the Pigeon River. rior, such jurisdiction is retroceded to the State. Upon publication in the Federal Register of an (Pub. L. 91–57, § 3, Aug. 9, 1969, 83 Stat. 100.) order of transfer by the Secretary of Agri- culture, the lands so transferred shall be a part § 403i. Secretary of the Interior authorized to of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park purchase necessary lands and available for the scenic parkway as author- ized by section 403h–11 of this title. The Secretary of the Interior is authorized to acquire on behalf of the United States by pur- (Pub. L. 88–415, Aug. 10, 1964, 78 Stat. 388.) chase, at prices deemed by him to be reasonable, § 403h–15. Conveyances to Tennessee of lands the lands needed to complete the Great Smoky within Great Smoky Mountains National Mountains National Park in the State of Ten- Park nessee, in accordance with the provisions of sec- tions 403 and 403a to 403c of this title; and the The Secretary of the Interior is authorized to Secretary of the Interior is further authorized, convey to the State of Tennessee, subject to when in his opinion unreasonable prices are such conditions as he may deem necessary to asked for any of such lands, to acquire the same preserve the natural beauty of the adjacent park by condemnation under the provisions of section lands, approximately twenty-eight acres of land 3113 of title 40. -

Great Smoky Mountains NATIONAL PARK Great Smoky Mountains NATIONAL PARK Historic Resource Study Great Smoky Mountains National Park

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Service National Park Great Smoky Mountains NATIONAL PARK Great Smoky Mountains NATIONAL PARK Historic Resource Study Resource Historic Park National Mountains Smoky Great Historic Resource Study | Volume 1 April 2016 VOL Historic Resource Study | Volume 1 1 As the nation’s principal conservation agency, the Department of the Interior has responsibility for most of our nationally owned public lands and natural resources. This includes fostering sound use of our land and water resources; protecting our fish, wildlife, and biological diversity; preserving the environmental and cultural values of our national parks and historic places; and providing for the enjoyment of life through outdoor recreation. The department assesses our energy and mineral resources and works to ensure that their development is in the best interests of all our people by encouraging stewardship and citizen participation in their care. The department also has a major responsibility for American Indian reservation communities and for people who live in island territories under U.S. administration. GRSM 133/134404/A April 2016 GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK HISTORIC RESOURCE STUDY TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME 1 FRONT MATTER ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................. v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................... -

Vacation Guide 2018

2018 VACATION GUIDE GATLINBURG.COM DON’T MISS OUT ON ALL THAT GATLINBURG HAS TO OFFER Download our app at GATLINBURG.COM The GatLinburg App • Find special offers and deals • Explore lodging options and book your stay • Discover special events, attractions and entertainment • Experience the wonder of the Smokies with stories and trip guides Install the official Gatlinburg app on your Android or iPhone device at Gatlinburg.com/app, and you’ll know exactly where to go, and how to get there. Join the Conversation gatlinburgtn @TravelGburg @visitgatlinburg Visit Gatlinburg gatlinburgtn +gatlinburg @visitgatlinburg TABLE j CONTENTS 2 THE BEST VIEWS OF THE SMOKIES 4 EVENTS CALENDAR 6 FROM ALL WALKS OF WILDLIFE 7 A SCENE FOR EVERY SEASON And there’s no 8 GETTING TO GATLINBURG IS EASY better time to go 9 GREAT WAYS TO Whether it’s a week-long vacation or a just a long weekend GET AROUND away, Gatlinburg is the perfect getaway for every member of 10 ATTRACTIONS the family. You’ll find a variety of amazing attractions, outdoor adventures, shopping, restaurants and family-friendly activities 20 WHITEWATER RAFTING in this charming mountain town. 22 DISTILLERIES It’s the kind of place that brings families together – where & WINERIES memories are made around every corner. And no matter how 26 DINING long you stay, it’ll stay with you for years to come. 32 ARTS & CRAFTS 36 SHOPPING 40 WEDDINGS SPECIAL FEATURES 44 ACCOMMODATIONS BEST VIEWS OF THE SMOKIES 62 SERVICES Amazing views from all over the Smoky Mountains. See page 2 68 GATLINBURG FROM ALL WALKS OF WILDLIFE CITY MAP The facts about about our furry friends. -

It's Like Living in a National Park

It’s like living in a National Park. Did you ever want to live in a National Park? The Preserve is the next best thing. The Preserve is a 700-acre mountain sanctuary that providies upscale remote living and modern amenities. The homes are nestled within a lush deciduous and evergreen Appalachian forest which presents magnificent views of it’s neighbor the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. The development is surrounded by the beauty of Smoky Mountain flora and fauna and greatly enhances the owners investment. The Great Smoky Mountains are known for their vast diversity of plant and animal life and boast far more species, both common and rare, than any other national park. Dan Barnett Blue Ridge Development, LLC 865-719-1455 [email protected] Click here to watch our movie. Pinnacle View, the community near the crest of English Mountain, provides a view over the valley to a All the homes are wide-angle vista of the magnificent bound by a covenant Smoky Mountains. designed to protect the wildness and beauty of the area. There has never been a community built like this one. Every care has been taken to step lightly and to repair any damage done by building roads and homes. No tree is taken unnecessarily, and extreme caution has been taken to ensure that the forest is left as pristine as possible. The middle mountain homesteads are known as Stillhouse Branch and look across the rolling valley to the Great Smoky Mountains. Trillium Ridge is the first neighborhood on the lower portion of the mountain. -

Required to Be Included Pursuant to Subsection (A) (13). Any Increase in the Formula Or Other Standard for Determining Payments

100 PUBLIC LAW 91-57-AUG. 9, 1969 [83 STAT. 81 Stat. 902. 42 use 1396a. required to be included pursuant to subsection (a) (13). Any increase in the formula or other standard for determining payments for those types of care or services which, after such modification, are provided under the State plan shall be made only after approval thereof by the Secretary." Approved August 9, 1969. Public Law 91-57 August 9, 1969 AN ACT [H.R. 2785] To auithorize the Secretary of Uie Interior to convey to the State of Tennessee certam lands within Great Smoky Mountains National Park and certain lands comprising the Gatlinburg Spur of the Foothills Parkway, and for other purposes. Be it enacted hy the Senate and House of Representatives of the state of United States of America in Congress assembled^ That the Secretary L^a^nd convey- ^^ the Interior is authorized to convey to the State of Tennessee, subject ^"'=^®' to such conditions as he may deem necessary to preserve the natural beauty of the adjacent park lands, approximately twenty-eight acres of land comprising a portion of the right-of-way of Tennessee State Route 72 (U.S. 129), and approximately forty-one acres comprising portions of the right-of-way of Tennessee State Route 73 east of Gatlinburg, which are Avithin the boundary of Great Smoky Mountains National Park. SEC. 2. The Secretary is further authorized to convey to the State of Tennessee, subject to such conditions as he may deem necessary to assure administration and maintenance thereof by the State and to preserve the existing parkway