The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Reality Creators

The Reality Creators An Epic Fairytale About Life On Earth By Christopher Hall The Reality Creators COPYRIGHT © 2021 BY CHRISTOPHER HALL ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ISBN: 978-1-7923-3330-9 (e-book) ISBN: 979-8-6183-2728-2 (paperback) Cover Design by Christopher Hall Goat photograph by Smuj Smujington Printed in the USA The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, write to the address below: [email protected] Upon a great scene has descended people who've come running to help from the right and the left, and no matter how they view the event and from what angle, they all care to be of service. This book is for them. We are like water drops that make up a watershed, a connected flow from the first drop wetting the soil to the millions more that make up a puddle and flow down a ditch, into a creek, that flows to the river, and out into the ocean that is all of us. That little drop is spread out everywhere and is one with all the other drops. Together they float up into the sky, rain down upon the earth, support life, water trees, plants, and animals, and fill the seas in a never-ending cycle. -

Narrative Spaces and Literary Landscapes in William Gilmore Simms’S Antebellum Fiction

GEOGRAPHIES OF THE MIND: NARRATIVE SPACES AND LITERARY LANDSCAPES IN WILLIAM GILMORE SIMMS’S ANTEBELLUM FICTION Kathleen Crosby A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature in the College of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: Philip F. Gura William L. Andrews Jennifer Larson Timothy Marr Ruth Salvaggio © 2015 Kathleen Crosby ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Kathleen Crosby: Geographies of the Mind: Narrative Spaces and Literary Landscapes in William Gilmore Simms’s Antebellum Fiction (Under the direction of Philip F. Gura) Genre affords a theoretical and conceptual framework for knowledge production and knowledge distribution. Rhetorically, genre affords a political, artistic, and ideological tool that enables a rhetor to respond to personal and cultural anxieties. Geographies of the Mind: Narrative Spaces and Literary Landscapes in William Gilmore Simms’s Antebellum Fiction examines ten of nineteenth-century American author William Gilmore Simms’s works, including three manuscript-only ones. Drawing upon rhetorical theory and narrative theory, this project uncovers the breadth of Simms’s rhetorical and literary practices within the confession narrative, the ghost story, the pirate romance, and the sentimental novel. I demonstrate that Simms’s texts both adhere to and subvert the boundaries of generic conventions and, in doing so, elucidate legal, psychological, and transnational concerns of the time. By focusing on the narrative spaces of Simms’s texts, I prove that Simms’s geographic spaces reverberate with hauntings that serve to mark moments of intellectual, personal, and historical disconnect, thereby voicing the disjunctive nature of antebellum southern spaces. -

Les Sophismes

Espaces Multimédia de la Copavo Stage « Traitement de texte » - Mars 2015 Les sophismes Oh ! un argument pour autoriser notre conduite ! Un sophisme, une argutie à attraper le diable ! William Shakespeare Définitions On appelle paralogisme et sophisme des raisonnements erronés ayant tous deux l’apparence d'un raisonnement logique. Mais contrairement au paralogisme qui n'est qu'une simple erreur de raisonnement, le sophisme est un raisonnement fallacieux, c'est-à-dire énoncé dans le but de tromper son interlocuteur. Le sophisme est donc en quelque sorte un paralogisme volontaire. Un peu d'histoire Dans la Grèce antique, les sophistes (de sophia, la « sagesse ») enseignaient l'éloquence et l'art de la persuasion. Orateurs prestigieux, leur but était de persuader l'auditoire des assemblées ou des tribunaux, même au mépris de la vérité ce qui leur valurent les critiques de Socrate, de Platon, puis d'Aristote qui fut le premier à établir une classification des raisonnements et, entre autres, à démonter les logiques fallacieuses à l'œuvre dans les sophismes. La Mort de Socrate (David, 1787) John Stuart Mill, dans son ouvrage Système de certains faits) ou de mal observation logique déductive et inductive (1843), a étudié les (dénaturation de certains faits) sophismes et proposé une classification en quatre • Le sophisme de généralisation provenant groupes : d'une fausse conception générale du • Le sophisme de simple inspection, ou procédé inductif, celle qui, selon Mill, sophisme a priori, quand la « solution » embrassant le plus grand nombre et la plus n'est pas démontrée mais présentée grande variété « d'inférences vicieuses ». comme évidente en soi. -

Accent Accent Is a Form of Fallacy Through Shifting Meaning. in This Case, the Meaning Is Changed by Altering Which Parts Of

FALLACIES Accent Accent is a form of fallacy through shifting meaning. In this case, the meaning is changed by altering which parts of a statement are emphasized. For example: "We should not speak ill of our friends" and "We should not speak ill of our friends" Be particularly wary of this fallacy on the net, where it's easy to misread the emphasis of what's written. Ad hoc As mentioned earlier, there is a difference between argument and explanation. If we're interested in establishing A, and B is offered as evidence, the statement "A because B" is an argument. If we're trying to establish the truth of B, then "A because B" is not an argument, it's an explanation. The Ad Hoc fallacy is to give an after-the-fact explanation which doesn't apply to other situations. Often this ad hoc explanation will be dressed up to look like an argument. For example, if we assume that God treats all people equally, then the following is an ad hoc explanation: "I was healed from cancer." "Praise the Lord, then. He is your healer." "So, will He heal others who have cancer?" "Er... The ways of God are mysterious." Affirmation of the consequent This fallacy is an argument of the form "A implies B, B is true, therefore A is true." To understand why it is a fallacy, examine the truth table for this implication. Here's an example: "If the universe had been created by a supernatural being, we would see order and organization everywhere. -

Appendix 1 a Great Big List of Fallacies

Why Brilliant People Believe Nonsense Appendix 1 A Great Big List of Fallacies To avoid falling for the "Intrinsic Value of Senseless Hard Work Fallacy" (see also "Reinventing the Wheel"), I began with Wikipedia's helpful divisions, list, and descriptions as a base (since Wikipedia articles aren't subject to copyright restrictions), but felt free to add new fallacies, and tweak a bit here and there if I felt further explanation was needed. If you don't understand a fallacy from the brief description below, consider Googling the name of the fallacy, or finding an article dedicated to the fallacy in Wikipedia. Consider the list representative rather than exhaustive. Informal fallacies These arguments are fallacious for reasons other than their structure or form (formal = the "form" of the argument). Thus, informal fallacies typically require an examination of the argument's content. • Argument from (personal) incredulity (aka - divine fallacy, appeal to common sense) – I cannot imagine how this could be true, therefore it must be false. • Argument from repetition (argumentum ad nauseam) – signifies that it has been discussed so extensively that nobody cares to discuss it anymore. • Argument from silence (argumentum e silentio) – the conclusion is based on the absence of evidence, rather than the existence of evidence. • Argument to moderation (false compromise, middle ground, fallacy of the mean, argumentum ad temperantiam) – assuming that the compromise between two positions is always correct. • Argumentum verbosium – See proof by verbosity, below. • (Shifting the) burden of proof (see – onus probandi) – I need not prove my claim, you must prove it is false. • Circular reasoning (circulus in demonstrando) – when the reasoner begins with (or assumes) what he or she is trying to end up with; sometimes called assuming the conclusion. -

Confirmation Bias!

Kritisk tenkning og utredningsmetodikk ved sakkyndige/vitenskapelige rapporter av Rune Fardal 01.01.2008 Sist oppdatert 06.04.2020 Side 2 av 356 INNHOLD: Innledning ...................................................................................................................................... 12 Fra Helsepersonelloven: ...................................................................................................................... 14 Forord .............................................................................................................................................. 15 Jussprofessor ........................................................................................................................................... 16 Hvorfor sakkyndige psykologer? ...................................................................................................... 16 Veiledende mal for oppbygging av den sakkyndige rapporten ................................... 17 Forside ....................................................................................................................................................... 18 Innholdsfortegnelse .............................................................................................................................. 18 1 Innledning ............................................................................................................................................. 19 1.1 Gjengivelse av mandatet med eventuelle tillegg ................................................................. -

Philosophism, Logic, Ethics, and Fallacies

Philosophism, Logic, Ethics, and Fallacies Periander A. Esplana January 2010 Abstract The primary objective of logic is the pursuit of truth. To attain truth by means of logic, one must determine the validity and expose the fallacy of a proposition or argument. The relationship and distinction between truth and validity play a vital role in the realm of logic to achieve truth that will delve the field of Ethics to avoid the illogical system called Philosophism. Ultimately, logic must not be separated to reality. What is Philosophism? It came from two Greek words: philos which means filial love and sophizo which means cunning device. The Greek word philos is the prefix word of PHILOSOPHY which means love (Gr. philos ) of wisdom (Gr. sophia ). The Greek word sophizo is the derivative of the Latin word sophisma which is the root word of sophism and sophistry. These words signify plausible but false reasoning. The synonymous word for sophism in terms of logic is FALLACY which means deceptive argument. It came from fallere the Latin word for “to deceive”. PHILOSOPHISM, then, simply means “love of deceptive reasoning” [1]. Even though modern logicians try to restrict logic within the bound of formal correctness or validity of an argument irrespective of the truth or falsity of its premises [2], yet when comes to the discussion of fallacy they inevitably addressed the question of the agreement or disagreement of a term, proposition and syllogism to fact and truth. Moreover, it must be pointed out that logic does not deals only with our internal thought through deductive inference (from universal to particular) but also with the external world through inductive inference (from particular to universal). -

Bingo Card 5

2020 Presidential-Debate B I NGO Appeal to Porcinocephalic Argumentum self-evident Psittacism Rodomontade refusal ad invidiam (44) (45) (43) truth (17) (5) Argumentum Choplogic Ipse dixit Argumentum ad Argumentum ad ignorantiam (26) (37) misericordiam ad hominem (19) (16) (15) Illeism Hyperbole Argumentum Erotesis ad crumenam (36) (34) Free (32) Space (14) Inoratio Argument Sloganeering Epiplexis Tapinosis elenchi from normality (46) (28) (47) (35) (7) Appeal to the Caconym Argumentum Argumentum Asteism common (25) ad judicium in terrorem (24) (18) (23) person (6) For entertainment purposes only. 2020 Presidential-Debate BINGO by Bryan A. Garner As you watch the candidates Tuesday, pay attention to their modes of ar- gument. Try to identify as many modes and rhetorical devices as you can. Some but not all of these arguments are fallacious. Each statement you isolate can qualify in only one category. Here are your categories: 1. Apophasis /uh-POF-uh-sis/: mentioning 11. Argumentum ad baculum: depending on something while disclaiming to mention it. (“I physical force. (“The military will intervene if I won’t even mention the lie you told last week decide it’s necessary.”) about . .”) 12. Argumentum ad antiquitatem: the wisdom of 2. Aporia: professing not to know where to the ancients. (“Our forebears were much wiser begin. (“I don’t even know where to start in than people today are, and they said [X].”) answering that point.”) 13. Argumentum ad captandum: appealing to the 3. Appeal to definition: use of dictionary defi- audience’s emotions. (“Most of us know people nitions. (“The dictionary defines [milksop, who have died unnecessarily.”) autocrat, sociopath] as X. -

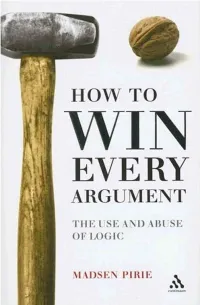

How to Win Every Argument: the Use and Abuse of Logic (2006)

How to Win Every Argument The Use and Abuse of Logic Also available from Continuum What Philosophers Think - Julian Baggini and Jeremy Stangroom What Philosophy Is - David Carel and David Gamez Great Thinkers A-Z - Julian Baggini and Jeremy Stangroom How to Win Every Argument The Use and Abuse of Logic Madsen Pirie •\ continuum • ••LONDON • NEW YORK To Thomas, Samuel and Rosalind Continuum International Publishing Group The Tower Building 15 East 26th Street 11 York Road New York, NY 10010 London SE1 7NX © Madsen Pirie 2006 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Madsen Pirie has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: 0826490069 (hardback) Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. Typeset by YHT Ltd, London Printed and bound in Great Britain by MPG Books Ltd, Bodmin, Cornwall Contents Acknowledgments viii Introduction ix Abusive analogy 1 Accent 3 Accident 5 Affirming the consequent 7 Amphiboly 9 Analogical fallcy 11 Antiquitam, argumentum ad 14 Apriorism 15 Baculum, argumentum ad 17 Bifurcation 19 Blinding with science 22 The -

Garybrodskymindcontrotechniq

MIND CONTROL TECHNIQUES Un-leash hell Edited by Gary Brodsky This book is compiled in no specific order, just like the human mind or situation follows no specific order. This book is powerful, frightening and deadly effective. CIA and other mind control experts works are all gathered here, they work- with no option of failure. MIND CONTROL TECHNIQUES: • Tell the Truth, the Whole Truth, and Nothing But the Truth. This can be highly effective and very convincing, if you know your subject material well, and are a good speaker. ... And IF the truth is really what you want your audience to hear and believe. The Truth, as a matter of habit, has some disadvantages: You have to learn and remember a whole lot of facts, and keep them straight in your head. The facts might not always be what you wish them to be. And, alas, the truth is sometimes very boring... • Lie This one is simple, straight-forward, and obvious. Just lie and say whatever you want to. It has the advantages that you don't need to memorize so many facts, and you can make up new facts when the currently-existing ones don't suit your purposes. The disadvantages are that you might get caught in a lie, and that would destroy your credibility. "You're never going to make it in politics. You just don't know how to lie." Richard M. Nixon Secret Lives of the U.S. Presidents, Cormac O'Brien, page 228. • Lie By Omission and Half-Truths This is also known as Suppressed Evidence. -

05. Phylogeny

Phylogeny Darwin deserves credit for the theory of natural selection, but the concept of phylogeny is the null hypothesis and thus a no-brainer. As observed in an earlier essay, phylogeny is the correct presumption regardless of the mechanism used to explain it. If natural selection is an unsatisfactory explanation, then let phylogeny be explained by something else. If creationists have issues with Darwin, then let them criticize Hennig and Kauffman. Darwin’s cardinal insight was the recognition of recursive environmental feedback. As cited in a previous essay, Daniel Dennett notes in Darwin’s Dangerous Idea that Paley asserted that the observed order in nature required intelligent design. Darwin then demonstrated that consciousness is not necessary for an intelligent design process. Adaptation can emerge and accumulate even without the help of foresight. There exists a creationist t-shirt that reads, “By Design and Not By Chance,” as if this were controversial. Actually, and apparently unbeknownst to creationists, there is no significant Darwinian dispute about this. In accordance with the second law of thermodynamics, species spontaneously decay into fragments incapable of mutual genetic communication. The resulting reproductively isolated sibling species are free to adapt independently. The resulting adaptations will be natural reactions to natural forces, like falling downhill, or the mutual forces of attraction and repulsion of magnetic poles. However, they will not necessarily be the best possible solutions under the circumstances because, as noted in a previous essay, complex systems are easily trapped in suboptimal modes (see Waldrop). Adaptation relies heavily on plagiarism and recruitment, such that the wheel need not always be reinvented. -

The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman 1 the Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman

The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman 1 The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman Project Gutenberg EBook, Tristram Shandy, by Laurence Sterne Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook. This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **EBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These EBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers***** Title: The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman Author: Laurence Sterne Release Date: October, 1997 [EBook #1079] [This file was first posted on October 25, 1997] [This file was last updated on October 23, 2003] Edition: 10 Language: English Character set encoding: ISO−8859−1 *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK, TRISTRAM SHANDY *** This eBook was produced by Sue Asscher with thanks to Stephen Radcliffe for the kind loan of his books! The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman. A work by Laurence Sterne (two lines in Greek) To the Right Honourable Mr.