http://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2011/11/20/the-long-unlikely-journey-cathy- greig/X7XXlhmjNYwtSQurlRmzKP/story.html

The long, unlikely journey of Cathy Greig

Who is the woman who lit out with Whitey Bulger, and stuck by him for all those years? Bookish, ambitious, she was no one’s image of a gangster’s moll — until she was one

By Sally Jacobs | G L O B E S T A F F

N O V E M B E R 2 0 , 2 0 1 1

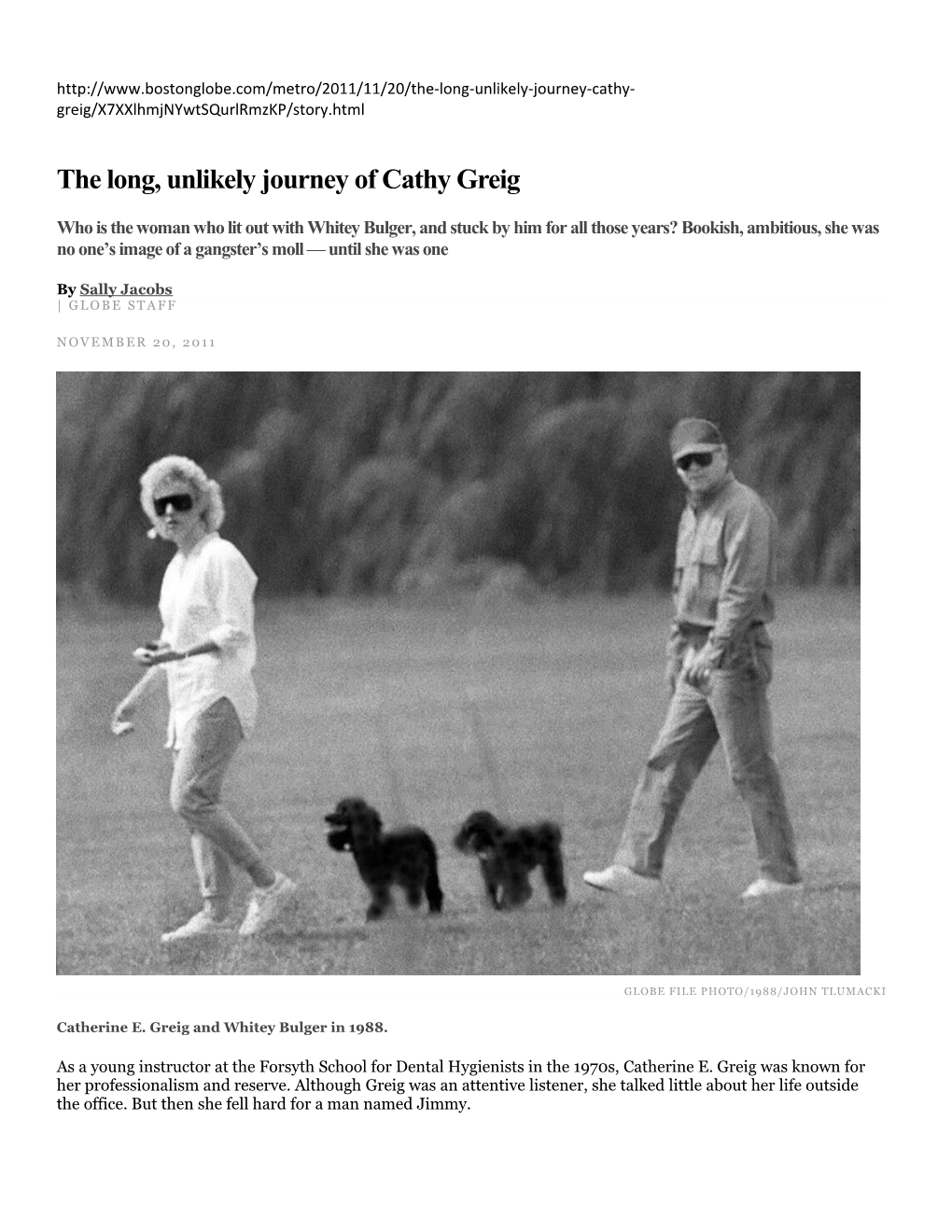

GLOBE FILE PHOTO/1988/JOHN TLUMACKI

Catherine E. Greig and Whitey Bulger in 1988.

As a young instructor at the Forsyth School for Dental Hygienists in the 1970s, Catherine E. Greig was known for her professionalism and reserve. Although Greig was an attentive listener, she talked little about her life outside the office. But then she fell hard for a man named Jimmy. Catherine Greig is shown as a senior high school student in a photo from the 1969 South Boston High School Yearbook, Reflections 69.

At the time she began dating Whitey Bulger in 1975, Greig, then 24, had already had her heart badly broken. Her first husband, a hotheaded firefighter and former Marine, had left her not long after they married for her own twin sister. But then there was “Jimmy’’ hotly pursuing her, delighting her with gifts of gold and furs and astonishing her with the breadth of his knowledge of history. For her cherished black poodles, there would be a pair of tiny diamond collars. That the ardent Jimmy happened also to be an ex-con and a notorious crime boss who was believed to have murdered her ex-husband’s brother didn’t seem to get in the way.

“She always talked about Jimmy. Jimmy this, and Jimmy that,’’ said Linda Hanlon, a former Forsyth dean who shared an office with Greig. “One day she came in and said, ‘Look what Jimmy gave me for my birthday!’ It was a beautiful Cartier watch, I mean really gorgeous. She liked it but she didn’t seem to realize what it really was or how valuable it was. I would say she was a little naive about some things.’’

Continue reading below Related

. Video: The Back Story - Catherine Greig . Special section: The pursuit and capture of Whitey Bulger

The relationship between Cathy and Jimmy has become the subject of intense interest not only among the teams of investigators who pursued the accused murderer and the inscrutable woman at his side for 16 years until their arrest in June, but also among the men and women of Southie who knew her before. Their Cathy Greig was no gunman’s moll but a bookish schoolgirl with a bent for numbers and later a dental hygienist in spotless white lab coat. How the mild-mannered high school senior who was voted the best-looking girl in her class ended up on the run with an alleged murderer wanted by the FBI, and with a $100,000 bounty on her head, is the subject of widespread speculation on Broadway, the boulevard that splices South Boston’s heart.

The questions heard on the street are much the same as those that have long intrigued law enforcement: What kind of a woman stays with a man like Bulger? What kind of a person launders his clothes and carefully writes his grocery list, enabling his life on the lam? Was she held by fear, or was she so besotted that she stayed of her own accord? Even if she was not initially aware of the deadly scope of his doings, as her lawyer maintains, surely she would have learned of the gruesome deaths with which he is accused when the charges were made public in 2000.

Greig, 60, is confined to the Wyatt Detention Facility in Rhode Island as she awaits trial on charges of harboring a federal fugitive. As prosecutors consider bringing additional charges against her, questions about her character have become central not only to the outcome of her case but potentially to that of Bulger’s as well. Greig has unique knowledge of their years on the run and perhaps of Bulger’s criminal reign.

Kevin Reddington, Greig’s lawyer, has declared that she is innocent of any criminal wrongdoing and will not assist prosecutors. Her only crime, he has declared, “is a crime of passion, falling in love with this gentleman.’’ Relatives of his victims, however, charge that Greig’s assistance enabled Bulger to remain at large and prolonged their suffering.

By the time the couple disappeared in 1995, just as prosecutors unveiled a lengthy indictment against him, Bulger and Greig had been together for two decades. During those years, Greig abandoned her career and became increasingly dependent upon her lover, more than 20 years her senior. Theirs was a relationship that seemed to gradually engulf her and erode her independence, transforming her from an ambitious professional into a self- effacing helpmate. And when she fled with him, some of her former colleagues were not entirely surprised. Catherine Greig with her two poodles.

“I figured she’d been with him for such a long while that maybe there was just no going back,’’ said Julia McCarthy, who attended Northeastern University a year behind Greig and later worked with her at Forsyth. “Maybe she was offered the chance to go and she found she didn’t have anything around here but him anymore so she decided to go. He was her life, you know.’’

. . .

This is a story about love. But it is also a story about a place.

What developed between Bulger and Greig was deeply rooted in the tangle of gangland rivalries that prevailed in their native Southie at the time they came together. Southie is a place of beauty, offering sweeping vistas of Boston’s skyline. It is also a place of grit, steeped in a history of violence and a legendary aversion to outsiders that has become cliché. It has been called the most insular neighborhood in Boston, and maybe any American city. But it is a label that no longer fits - few sections of town have changed more rapidly.

Although Greig and Bulger were raised within a mile of each other, they were born into opposite ends of the local culture. Bulger started out in the scrappy Old Harbor housing project, one of the country’s first public housing developments. Greig grew up some blocks to the east in the more affluent Irish neighborhood known as City Point, just blocks from the curved arc of Pleasure Bay.

The daughter of a Scottish-born machinist and a Canadian housewife, according to her birth certificate, Greig was the firstborn of twins. With their demure smiles and sometimes matching outfits, the Greig girls were often hard to tell apart, and they did not hesitate to fool those trying to sort them out. As one longtime neighborhood resident describes them, “They were very neat, very pulled together. They were the good-looking Irish-scrubbed girls. You just couldn’t always tell which was which.’’

But to those who knew them, Cathy and Margaret could not have been less alike. Cathy was the more focused of the two, a gentle girl with her eye on a life beyond Southie’s tavern-studded streets. A passionate lover of animals, she possessed a sunny outlook that attracted many friends. Margaret was the mischievous twin, prone to antics and adventure with the boys. Cathy sought to expand her horizons through reading, her nose always deep in a book. By the time the twins were in South Boston High School, Cathy had earned a reputation for her facile mind and aptitude for numbers. In 1969, her senior year, Cathy was the co-business manager of the class yearbook, called Reflection, and she had already determined her professional path.

In her yearbook entry, Greig wrote that her personal ambition was “to have a medical career.’’ Her most prized possession was “my black teasing comb.’’ She described her legacy to the school as a determination “to live, laugh, love and learn.’’ Margaret yearned to be a secretary. She left for the school “all my forged absentee notes.’’

While many young men were attracted to Greig and her arresting blue eyes, more than a few kept an awed distance.

THE BOSTON GLOBE

The FBI announced a $1 million reward for information leading to the arrest of James 'Whitey' Bulger in November 2000. Catherine Greig is shown.

“A lot of us wanted to go out with her. But Cathy was from the Point and I was from the flat,’’ explained one classmate who asked not to be identified. “So there was no way.’’

The streets of South Boston have changed a great deal since the mid-1970s when the violent response to court- ordered busing cast the shattered neighborhood as a national symbol of racial intolerance. With the development of the sprawling Seaport district over the past few years, young urbanites are flooding in and the sound of hammers transforming the old three-decker homes into condominiums is a constant backdrop. Yet there is one tradition that remains largely unaffected by the tide of change, and that is the code of silence that has long prevailed in Southie. At least it remains the rule for some when the subject has anything to do with the infamous Whitey. Bulger is securely locked in the Plymouth County Correctional Facility, his criminal empire is long gone, and many of his former associates talk and write freely about him without apparent consequence. But many in the neighborhood, and even some who no longer live there, still don’t want to say a word about him. Or about Greig.

High school classmates of Greig’s abruptly hang up the phone when asked about her. Class officers, who still live in the area, brusquely turn away. Boston City Councilor Bill Linehan, who was a member of the class of 1969, declined to be interviewed. Those that are willing to talk about her insist that their names not be used.

“Are you kidding? Nobody wants to talk about her,’’ said one Southie resident who attended school with Greig.

By the time Greig and her classmates received their high school diplomas, Bulger had emerged as a ruthless enforcer for a local gambling and loan shark operation. Hardened by nine years in federal prison, the compact hood was fast becoming a feared figure in his trademark sunglasses and baseball cap. When a young man named Donald McGonagle was shot dead in the front seat of his car in November 1969, police attributed the killing to general warfare between rival gangs - but at least some in Southie blamed Bulger.

One of McGonagle’s brothers, Paul, was the head of a street gang called the Mullins that evoked fear on Southie’s streets. The McGonagle brothers believed that Bulger, affiliated with a rival group, was the triggerman, according to McGonagle family members, and his name became a household curse. In his 2006 book, “Brutal,’’ Kevin Weeks, one of Bulger’s closest associates, confirmed their suspicion: He wrote that Bulger had intended to kill Paul McGonagle but took out Donald by accident. Bulger allegedly corrected his error in 1974 and now stands accused of murdering Paul McGonagle as well.

How aware Greig was of such bloody matters is unclear. She certainly knew of the players. The McGonagles lived just one block away from her family home on Fourth Street, and a determined Robert A. McGonagle, another McGonagle brother, had eagerly pursued her. And Bulger’s notoriety was inescapable - despite his gangster doings, he was widely known and even admired as a kind of local Robin Hood. He routinely donated money to local sports teams or needy families and distributed turkeys in the housing projects over the holidays.

Greig trained her gaze beyond such local dramas. It was a career, not settling down with the boy down the street, that topped her list of ambitions. At the time of her graduation, Greig was undecided whether she wanted to be a veterinarian or a dental hygienist. But the following year she enrolled in a two-year program at the Forsyth School for Dental Hygienists, then affiliated with Northeastern University. Several former participants in the program remember that Greig swiftly earned recognition. In 1971, her second year of the program, Greig was one of a handful of students who were chosen by Dr. Sigmund S. Socransky, a prominent periodontist and scientist, to do research in his lab at the Forsyth Institute.

“It was a real feather in her cap,’’ recalled Patricia Connolly-Atkins, a former associate dean at the Forsyth school. “Sig was very particular about who he worked with and he chose Cathy. She was a very impressive person.’’

It was a pivotal year for Greig. Just before the second year of the dental program began, she married Bobby McGonagle in St. Brigid’s Catholic Church. Greig, just 20, was smitten by the headstrong McGonagle, three years older than her. Although McGonagle hung at the periphery of his elder brother’s doings, he frequently wound up in bar fights and scrapes of his own, according to family members.

As she would confide to her hairdresser in California decades later, Greig had a taste for “bad boys’’ when she was young. But the marriage between the gregarious McGonagle and the bookish Greig got off to an uneven start. On the day the couple returned from their honeymoon, as one McGonagle family member who asked not to be identified recalls it, “Bobby threw up his hands and said Cathy had sat on the beach and read books the whole time. They were just very different people.’’

McGonagle was temperamentally more attuned to Margaret, the more boisterous of the Greig sisters, according to former classmates and McGonagle family members. Once, when he was found in a compromising situation with Margaret, he joked to family members that he had confused the twins. By the middle of 1973, McGonagle had moved out, according to the couple’s divorce papers, leaving Greig with their pair of miniature Schnauzers. At some point he began a relationship with her sister, then named Margaret McCusker. McCusker had married James McCusker while in high school but the relationship collapsed in 1974, according to their divorce papers. When McGonagle signed a summons relating to his divorce from Greig in 1976, it was Margaret McCusker who signed as the witness.

Although McGonagle and McCusker never married, their relationship endured until he died in 1987. His death notice mentioned her as his “dear friend.’’

Greig was heartbroken by her husband and twin sister’s betrayal, according to family and friends. Although she divorced McGonagle in 1977 and eventually rekindled her relationship with her sister, some say Greig never fully recovered from the blow.

“Cathy never had much confidence,’’ recalled one of Greig’s high school classmates who asked not to be identified. “You’d tell her how beautiful she was and she’d say, ‘Oh, no, I am not.’ And you could tell that she actually meant it. So how was she going to survive this?’’

She survived by immersing herself in her work. Although Greig mentioned her turbulent domestic life to some at Forsyth, she did not go into detail. After earning an associate’s degree in dental hygiene in 1972, Greig began working on a bachelor’s degree in health science at Northeastern’s University College, which let her take classes at night while she taught at Forsyth during the day.

Like many of the other young women employed at Forsyth, Greig worked long hours, and she was well-liked by the collegial group. In Greig they found someone who was not only deeply committed to the dental program but sensitive in her dealings with faculty and students. One of her teachers describes her as “an exceptional person. She had a great deal of integrity in what she did.’’

Greig was a good listener and some of the other staffer members confided in her. But she offered little in return.

“Cathy was a very private person, very close to the vest about many things,’’ said Connolly-Atkins, the former associate dean at Forsyth.

By 1975, that had changed. By then, Greig was dating “Jimmy.’’ Charles “Chip’’ Fleming, a retired Boston police detective and former member of the Bulger Task Force, says that he was told that Greig had deliberately sought Bulger out, had even tracked him down at one of his favorite bars, The Triple O’s Lounge. Her motive, at least in part, may have been to get back at her unfaithful husband.

“Cathy knew Jimmy hung out there and she knew she had to go there to create a relationship,’’ said Fleming. “I received information that she did it to get back at her former husband, plain and simple.’’

However the relationship began, some of her dental school colleagues were pleased to see her so enamored.

“After all she had been through with her ex-husband, I think she just wanted to be loved,’’ said Linda Hanlon, the former Forsyth dean. “And Jimmy was very good to her. Certainly, in a material way he was.’’

After the two had been dating for a while, some of Greig’s colleagues invited the couple over for dinner or suggested a double date. They wanted to meet this Jimmy fellow who seemed to have an unending supply of jewelry and furs for Cathy. But Greig always declined, always had some other engagement. Hanlon, who considered Greig a friend, was perplexed until one day, another teacher pulled her aside and said, “Don’t you know who Jimmy is?’’ Hanlon recalled. “I said, ‘I don’t have a clue.’ And they said, ‘Jimmy Bulger; you know, Whitey Bulger.’ I knew who that was of, course. I think my first thought was that she could have done better.’’

Forsyth staffer members soon learned that there were two versions of the man. While the Whitey Bulger that they knew from news stories was a rising gangster involved in the Southie rackets, Greig portrayed him as a local hero.

“She told how he had paid to have someone’s teeth fixed, how he gave money and things to people who needed them, on and on,’’ recalled one former colleague who asked not to be identified. “She was totally and completely enthralled with him. I guess in the culture of South Boston he is either God or the devil and to her he was God.’’ Just as some of Greig’s colleagues had given up on the idea of having the couple over for dinner, now some surrendered hopes of having much of a friendship with Greig. Although Greig did not say so explicitly, now that she was with Bulger there were certain rules to be observed. You were not to call her at home. You were certainly not to drop in on her on a weekend. And if you happened to see Bulger waiting for her outside of Forsyth, you kept right on walking.

“A lot of us socialized outside of work, but Cathy did not,’’ said Connolly-Atkins. “I didn’t find it particularly odd. It was just the way it was.’’

By the end of the decade, Greig could be proud of several achievements. In 1978, after six years of classes, Greig was awarded a bachelor’s degree of science with honors and was working at Forsyth as the clinic coordinator for second-year students. She had also been instrumental in the development of an innovative computerized grading system called “The Clinic Manual.’’ As Julia McCarthy describes it, “Cathy was the driving force behind the manual. . . . It was brilliant.’’

Bulger, however, was not happy about Greig’s blossoming career. Greig confided in some of her colleagues that he had urged her to stop working, in part because he wanted her to devote more time to him. Bulger, as usual, eventually got what he wanted.

In 1982, Bulger and Greig began sharing a three-story condominium in a Quincy apartment complex called Louisburg Square South. Although Greig is listed as the former owner of the unit in city property records, investigators believe that Bulger put down the $96,000 in cash to purchase the unit. There was no mortgage.

By that time, Bulger had established himself as a preeminent figure in Boston’s organized crime scene. Having been recruited as an FBI informant in 1975, Bulger had allegedly embarked on a string of brutal killings that ultimately left 19 people dead. One body was buried just a few hundred yards from the couple’s new condo on the banks of the Neponset River. He would not be charged with the killings for more than two decades.

At the same time, Bulger had expanded his criminal empire southward into Quincy and the rest of the South Shore, and authorities struggled to keep track of his doings. Local detectives maintained a steady surveillance of the couple’s unit - No. 101 - and routinely went through their trash, which included grocery lists written in Greig’s elegant script. For a brief period in 1984 the US Drug Enforcement Administration placed a bug in the condominium window and got an earful of Bulger’s legendary temper.

“It was the middle of the night and Bulger had come home in a rage,’’ recalled one former member of the task force. “He was screaming at Cathy that she cares more about the dogs than she does about him. He says if she doesn’t stop, if she doesn’t pay more attention to him, the walls will be covered in blood. She yelled right back at him. It was just a long crazy night.’’

There were other crazy nights. During his years in prison, Bulger had participated in a government study of the effects of LSD in return for a slight reduction in his sentence. An apparent side effect for Bulger was the horrifying nightmares that tortured him for years and left him sweating and sleepless in the middle of the night. Notoriously nocturnal, he often worked through the night, and when he arrived at the condominium in the early morning hours he insisted that Greig be waiting for him fully dressed and made up.

“Cathy had to be perfect all the time,’’ said Fleming, the task force member. “If he was up in the middle of the night, then she was up. And she better look good.’’

Greig wasn’t the only one waiting for the sound of Bulger’s boots at the door. Although Bulger had been a legendary womanizer in his younger years, by the 1980s he had reduced the number of his girlfriends to two. One was Greig. The other was Teresa Stanley, a single mother of four children with whom Bulger had been involved since the 1960s. While Bulger was famously unpredictable as he evaded law enforcement investigators, he reportedly maintained a predictable routine with the women in his life. Each afternoon, he left the condo he shared with Greig and headed to Stanley’s for an early supper. He spent the evening moving around the city until he returned to No. 101 in the early morning. Greig was aware of Stanley but Stanley did not know of her competition until Greig informed her in 1994. A decade younger than Stanley, the best-looking girl in the class of 1969 was nonetheless not quite good-looking enough. In 1982, just after she turned 31, Greig had breast implants, according to a 2010 ad placed in the newsletter “Plastic Surgery News’’ by the FBI. The ad, crowned by the headline, “Have you treated this woman?’’ says that Greig also had eyelid reconstruction, a facelift, and liposuction. Whether it was Bulger or Greig who desired such enhancements is unclear. Either way, it was Bulger, according to a member of the task force, who paid for it all.

As she lived with Bulger in the early 1980s, it seems unlikely that Greig could have been unaware that her Jimmy was far from the Robin Hood of her vision. By then, Bulger was living with a vivid awareness of his growing list of enemies. During the four years that the couple lived in the unit, the shades were often pulled down and cardboard was taped to the windows of the outside door. Bulger installed a sophisticated alarm system and when he returned home at night, he carefully parked his car at the condo’s door in case he needed a quick getaway.

Some investigators question why Greig didn’t leave then, when it must have become starkly obvious what sort of man she was with.

“The big question about Greig was and always will be: Was she trapped or was she truly devoted to this man?’’ said Pamela Hay, a former member of the Bulger task force and now a private investigator. “I believe she was devoted, because this woman had a gazillion opportunities to leave and she chose not to. Love can do strange things to a person.’’

As Bulger continued to expand his empire, Greig was confronted with more turbulence in her sometimes chaotic family life. Early on a May morning in 1984, her brother, David S. Greig Jr., shot himself in the head in the family’s South Boston home, according to his death certificate. Greig, then 26, had a history of drug and alcohol abuse, according to a police report of the death.

Greig was so devastated by her brother’s death that she left her job. Invited to return some time later, she was still obviously grief-stricken. When colleagues offered their condolences, some recall, Greig broke down in tears. Unable to fully focus on her job, Greig left Forsyth for good at the end of the semester.

“Cathy chose what she chose,’’ sighed Hanlon, the Forsyth dean. “She was having a lot of stress in her family life, and Whitey was there to take care of her, and so she just left.’’

At some point during the 1980s, Greig began working as a part-time hygienist for Milton dentist Dan Sweeney. Like her Forsyth colleagues, Sweeney was impressed with Greig’s work, which he describes as, “A plus. Triple A- plus.’’ The other hygienists were impressed as well with her fur coat.

“We knew that Cathy lived in Louisburg Square and she always had a nice car,’’ said Sweeney. “Cathy just lived well.’’

By the late 1980s, Greig was living well enough that she no longer needed to work at all. She left her job with Sweeney and in 1987 her hygienist’s license expired. By then, Greig and Bulger had moved to a trim gray ranch house in Quincy’s Squantum section, just blocks from the ocean. Once again, Greig’s name went on the deed when the house was purchased for $160,000 in cash in 1986. Once again, there was no mortgage.

Four months before the couple moved to their new home that fall, Greig’s father died of cirrhosis of the liver caused by “chronic ethanolism,’’ or alcoholism, according to his death certificate. With two members of her immediate family now dead and no job to preoccupy her, Greig seemed to grow increasingly dependent on Bulger. Often the two of them could be seen walking their black poodles, Nikki and Gigi, in South Boston or lounging in deck chairs at Columbia Park. Neighbors noticed that Greig rarely left the house by herself. The only visitors she seemed to receive were her mother and sister and the dog groomer.

“She was always with him,’’ noted one neighbor who asked not to be identified. “She didn’t seem frightened of him. She was just never without him.’’

Neighbors could hardly ignore the new arrivals to Squantum. Within weeks of their purchase of the house, Bulger launched a renovation project that included removing the front door from its position near the road. Visitors - or enemies - had to walk the length of the house to the back door in order to get inside. Bulger also had all the windows replaced, a cathedral ceiling installed in the living room, and two bathrooms remodeled, according to a city renovation permit.

One neighbor, watching as the workmen toiled on the project for weeks, could not resist walking down the street and introducing herself to the man whose identity she well knew.

“I went up to him and said the neighborhood was going to have a tea for him,’’ recalled the neighbor. “He said, ‘No, no! Don’t do that.’ I said, ‘We are going to have a welcome to the neighborhood party for you, then. What day would be good for you?’ He said, ‘Oh my God! No.’ ’’

While some neighbors found Bulger prickly, they considered Greig a welcome addition. Always ready with a smile, Greig knew her neighbors well enough to be aware of special occasions such as a wedding or birthday and invariably left small gifts of chocolate and garden tomatoes on their doorstep.

“One thing she always did was make sure the neighborhood dogs were comfortable,’’ said one neighbor. “If she had an extra dog bed and she saw that a dog was lying outside on a hard stoop, she dragged it over and gave it to the dog.’’

. . .

In January 1995, federal law enforcement officials who had investigated Whitey Bulger for years unveiled a sweeping indictment that charged Bulger with two counts of extortion and ten counts of racketeering. There was no mention of murder.

Tipped off to the indictment two weeks before it was unveiled, Bulger fled not with Greig but with his longtime girlfriend, Stanley. Police looking for Bulger first checked Stanley’s home and then headed to Squantum, armed with a search warrant. But before they could get to the back door, Greig stopped them in their tracks. Alone in the driveway, Greig declared that police were not coming into her house. And, according to testimony given by an FBI agent in July, it was an expletive-laced rebuff.

One month later, Bulger was back. Stanley was homesick and tired of the road. This time, Bulger wanted Greig to go with him. Greig, seemingly untroubled that she was his second choice, agreed and they arranged to meet at Malibu Beach in Dorchester at night. Greig would take no luggage, just the clothes on her back. Nikki and Gigi would have to stay behind with her sister.

In testifying at Greig’s detention hearing, Kevin Weeks, Bulger’s longtime criminal associate, described picking Greig up in Thomas Park on the night that she was to meet up with Bulger and flee. Greig, Weeks recalled, arrived with only her purse in hand.

She was clearly nervous. The two exchanged small talk but said little of substance. As Weeks drove around the city for more than an hour to make sure he was not being followed, he urged Greig to remain calm.

“I told her, you know - I kept on driving around and stuff and I told her, you know, to relax,’’ said Weeks.

Finally, Weeks pulled the car to a stop at Malibu Beach. Within minutes, Bulger approached the car on foot.

“She smiled when she saw him,’’ Weeks testified. “And he come - he come walking out of the dark and walked up and then shook my hand and gave her a hug.’’

Greig got into Bulger’s car. And then they were gone.

Sally Jacobs can be reached at [email protected].