Enhancing employability for students on vocational programmes at the University of Plymouth - Sarah Watson-Fisher

Introduction

This paper looks across the health professions to identify and explore the range of career pathways available to them and makes some recommendations to embed employability services and activities within Schools and curricula.

The outcomes of this paper are applicable to students on most vocational programmes.

Whilst the NHS is the largest employer of health professionals it is not the only one and in the increasingly competitive market for students, employability will continue to be a key driver of student choice about where to study.

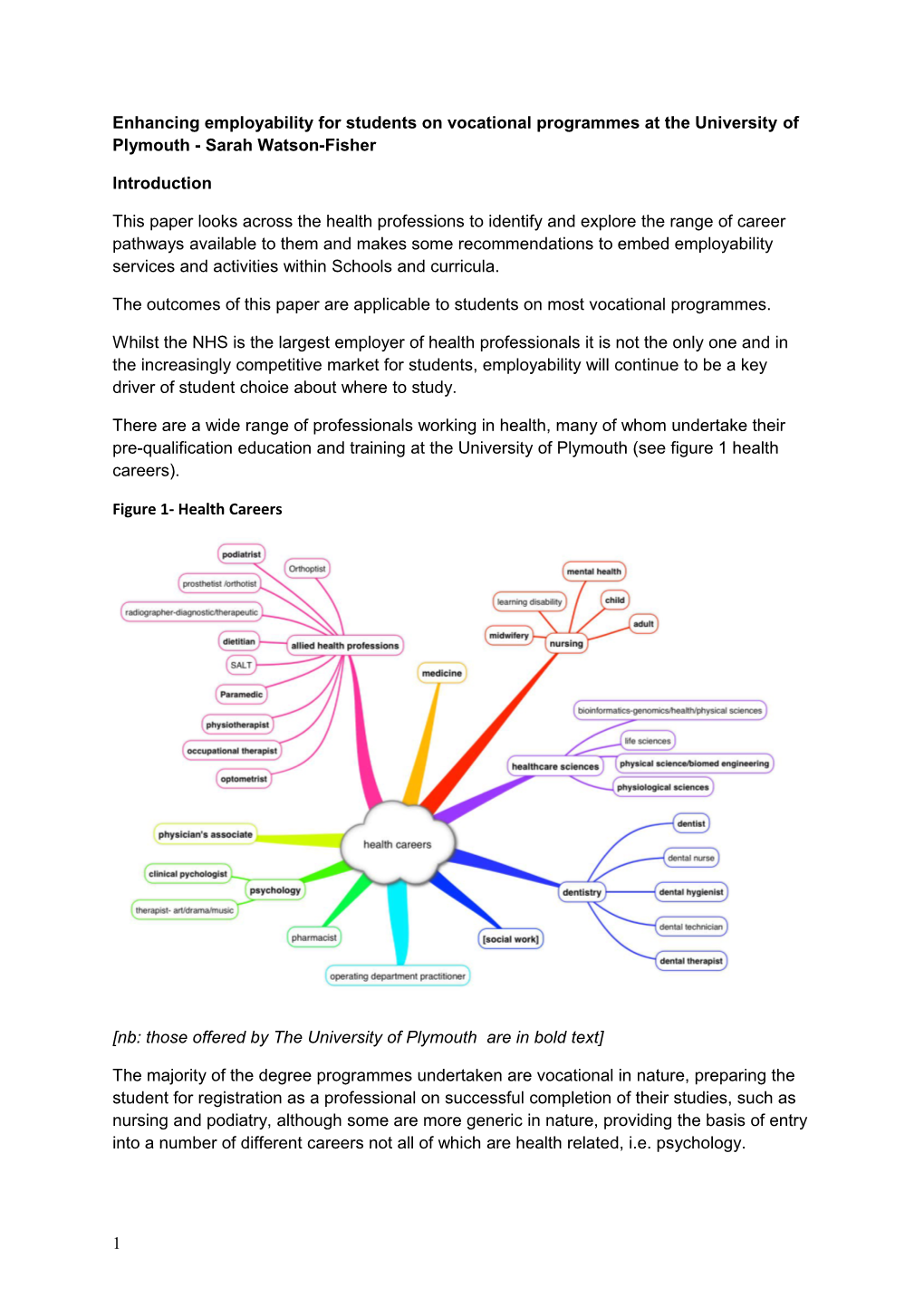

There are a wide range of professionals working in health, many of whom undertake their pre-qualification education and training at the University of Plymouth (see figure 1 health careers).

Figure 1- Health Careers

[nb: those offered by The University of Plymouth are in bold text]

The majority of the degree programmes undertaken are vocational in nature, preparing the student for registration as a professional on successful completion of their studies, such as nursing and podiatry, although some are more generic in nature, providing the basis of entry into a number of different careers not all of which are health related, i.e. psychology.

1 The majority of these professions are also professionally regulated and students apply for full registration either upon completion of their undergraduate studies, ie nursing, physiotherapy, or after an additional period of post-graduate training, i.e. medicine, pharmacy.

Funding

There are currently a number of different approaches to funding undergraduate health professions’ degrees:-

1) NHS funding- Nursing, Midwifery and Allied Health Professions/Student Bursaries The NHS has funded the education of these professions. Students receive an NHS bursary to cover their fees, and the universities are contracted to work with local NHS employers to provide these programmes, receiving receive funding to deliver the education and support clinical placement learning.

The NHS also sets annual commissioning numbers (based on local workforce forecasts) for each university and professional group as part of its annual contracting.

The key disadvantages of this approach have been that it overlooks the significant staffing needs of non-NHS employers and only covers some professions, leaving the rest to take out a loan to pay their course fees (see below).

2) HEFCE funding- Medicine, Dentistry/Student Loans

Undergraduate medicine and dentistry is funded via HEFCE who allocate annual funding to those universities providing training, whilst students obtain a loan from the Students’ Loan Company (SLC) to cover their fees. HEFCE in partnership with the NHS agrees annual intake numbers for each professional with each university medical and dental school1.

3) HEFCE funding- general- Paramedicine, Pharmacy, Healthcare Sciences, Optometry, Psychology/Student Loans

HEFCE also provides annual grants to universities as a contribution towards teaching and research activities; The proportion of an institution’s total income that comes from HEFCE will also depend on the fees it charges, its activities and the money it raises from other sources2.

Students on these programmes are not eligible for an NHS Bursary and so obtain a loan from the SLC. Professions including pharmacy, social work, paramedicine fall into this category. Significantly, there are no annual commissioning numbers set for these subject areas, with universities free to recruit to their own capacity, despite concerns raised by both the NHS and HEFCE about potential oversupply.3

1 Healthcare, medical and dental education and research- HECE’s role. hefce.ac.uk (accessed 03/09/16)

2 Guide to funding 2016-17. How HEFCE allocates its funds. HEFCE (2016)

2 Funding Changes

The NHS funding model outlined above in point 1 ceases in August 20174. Student nurses, midwives and allied health professions will then need to apply for student loans, bringing them in line with other health professions. This will also see the end of Universities’ NHS contracts and funding for teaching, although placement funding will remain for the current time.

These changes will create a more competitive the market for the education and training of health professionals56 and will raise expectations from students who will now all be fee- paying about securing meaningful employment upon qualification, and having access to resources to help them do so.

It is important that universities can articulate the added value that students can obtain from studying with them, and support them to develop their employability by identifying the full range of careers that are open to them, not just those within the NHS (see figure 2- career options) and provide them with opportunities to develop the additional skills and experiences that will equip them for these careers, ie developing business management skills for those considering becoming self-employed.

Figure 2:- Career options- health professionals

3 Healthcare, medical and dental education and research- Pharmacy graduates. hefce.ac.uk (accessed 03/09/16)

4 Reforming healthcare education funding: creating a sustainable future workforce. DH Workforce Development Team (July 2016)

5Innovative new degree programme for Nursing- January 2015 bolton.ac.uk (accessed 03/09/16)

6 New School of Nursing announced for the North East. June 2016 sunderland.ac.uk (accessed 03/09/16)

3 Graduate Employment

The ability of students to obtain ‘graduate level’ jobs is an important determinant of a successful degree programme, and will become more so with the introduction of the Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF), which will measure graduate employment as a key metric7.

Health professionals enjoy good levels of graduate employment, earning a salary above the average for a graduate (£25,000 p.a v £20,637 p.a), with nursing and medical practitioners taking the first and third place of top ten professional and managerial jobs held by first degree graduates in the UK8.

The NHS sector is the main employer of health graduates, although there are also job opportunities available in other non-NHS providers so unemployment is generally low

The picture is slightly different for psychology graduates with 63% in employment 6 months after graduating, whilst 15% go onto further study, the majority (60% of whom opted to for Masters degrees in psychology specialisms or mental health9. This reflects the more generic nature of the undergraduate degree, and the requirement for a post-graduate qualification as the route into a health/clinical career role.

7 ‘Teaching Excellence Framework. Technical Consultation for Year Two’. BIS. May 2016’

8 What do graduates do? HECSU (October 2015)

9 What do graduates do? HECSU. 2015

4 Dental graduates have a higher mean starting salary than any other discipline (more than £30,348 P.a) plus the highest employment rate of any UK degree course10. A recent strategic review of the future workforce has found that the supply of dentists was forecast to significantly exceed future demand and recommended changes be made to reduce the student intake to avoid over-supply and under-employment.11 The increasing competition for both training places and jobs as a result of this oversupply mean that, diversification and marketing have become important.

Employment Sectors (See figure 2)

The NHS has traditionally been the main employer for health professional graduates, given that given that the practice placement component of most health professions programmes are undertaken in NHS settings of care and that the NHS is the largest employer of health professionals in the UK.

It not surprising then that much careers information is focused on mainstream NHS service delivery roles12 and career progression, and an assumption that most health professionals will apply for these upon qualification.

The majority of newly qualified professionals usually obtain an entry-level service delivery role, either as a period of consolidation/preceptorship, or as a condition to obtaining full professional registration (i.e. medicine, pharmacy and general NHS dentistry), although some may opt to work in a different field from the outset, i.e. a physiotherapist with an interest in sports medicine may go straight into this field upon qualification, or go onto do further specialist post-graduate qualifications.

Medicine is unique in that it there are clear career pathways with formal training routes into a wide range of specialties, with all newly qualified doctors undertaking a 2 year common foundation programme before they can register as an independent practitioner and then choose their specialty training route.

It is worth noting that NHS services are increasingly being delivered by a wide range of organisations, for example

Hospices that provide end of life and palliative care Charities that provide Neurorehabilitation services Independent providers that provide psychiatric services or children’s services Community Interest Companies that provide community, mental health and learning disability services

10 What Do Graduates Earn? Thecompleteuniversityguide.co.uk accessed 12/09/16

11 A strategic review of the future of dentistry workforce. Informing dental student intakes. CfWI. 2012

12 ‘Health Careers ’ https://www.healthcareers.nhs.uk accessed 13/09/16

5 The distinction is an important one to understand, as each organisation may have different values, terms and conditions of employment or approaches to continuing development which may influence their employment choices of students.

Other key employers of health professionals are local authorities and the social care sector, with approximately 50,000 nurses working in the care sector for private care home providers.13

Indeed some services such as palliative care, or neurorehabilitation care which are often are frequently provided by charities, are key areas of employment, particularly for physiotherapists and occupational therapists.

The NHS also employs significant numbers of health professionals in its more corporate activities such as service and workforce commissioning/redesign and public health, although these roles usually require extensive professional experience and expertise

In addition, some professions are more likely to be working commercially rather than in the NHS, i.e. pharmacists and optometrists often work for either corporates or run their own high-street dispensing services as independent contractors.

Physiotherapists too, often work independently or within the sports and leisure industry where their skills are highly sought after.

Health professionals such as pharmacists, healthcare scientists, podiatrists, dentists and doctors can also be employed in companies involved in the design, development and marketing of medical devices such as prostheses and digital health technologies, and research and development in areas such as the pharmaceutical sector or biomedical engineering.

A study by the British Neuroscience Association showed that neuroscience graduates worked in research, clinical sciences, biotechnology, the pharmaceutical industry, medical devices industry, contract research organisations, regulatory affairs, policy and research administration, publishing and the media14

Some health professionals also have a strong track record of self-employment/private practice, i.e. dentists, optometrists, physiotherapists, doctors, paramedics and clinical psychologists15.

Dental graduates have a number of career pathways to choose from, including specialist training in one of 13 clinical dental specialties, although the majority are likely to choose to work for corporates or setup their own practices. It is not surprising that a survey of newly

13 The state of the adult social care sector and workforce in England. Skills for Care. 2015

14 Career Options with a neuroscience degree. Careers & Employability Service. Univ of Nottingham 2015

15 ‘Careers: Your journey into psychology’ careers.bps.org.uk. accessed 13/09/16

6 qualified dentists identified that curricula need to have a greater emphasis was non-clinical subjects such as business management and communication skills16.

As health professionals gain more experience they may diversify their roles and work in other sectors.

Some may go onto to roles as advisors or expert practitioners responsible for developing and monitoring standards of practice, either for their own professional representative bodies/ regulators, or service regulators.

There are also opportunities for health professionals to consider non-health related career changes, and seek to re-train or move into roles where they can apply their professional knowledge in a different sector, i.e. medico-legal work, healthcare journalism, the travel industry, management consultancy.

There are a growing number of resources aimed at medical professionals who wish to diversity their careers in this way17’18, including the NHS careers website19.

Working overseas

Registered health professionals are also highly sought after to work in other countries’ health systems.

Demand for health workers has continued to increase in all OECD countries, with health and social sector jobs accounting for 10% of total employment in these countries20, although for UK health professionals there are 4 key destinations-Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the USA21.

The two biggest staff groups to work overseas are doctors and nurses/midwives which reflects their size in relation to the other professions.

The number of doctors applying to the GMC for a Certificate of Good Standing (CGS, required to register overseas), has remained steady at about 4,700 applications a year22,

16 ‘What I wish I’d learned at dental school’ Oliver G et al. British Dental Journal 221: 2016

17 ‘career opportunities’ medicfootprints.org accessed 13/09/16

18 ‘Alternative career paths for doctors’ medicalsuccess.net accessed 13/09/16

19 ‘Alternative roles for doctors’ healthcareers.nhs.uk accessed 13/09/16

20 Focus on Health Workforce Policies in OECD Countries. March 2016. www.oecd.org/health

21 ‘A decisive decade. The UK nursing labour market review 2011.’Buchan J & Seccombe RCN Labour Market Review. 2011

22 ‘5,000 doctors a year considering leaving the UK to emigrate abroad.’ Kenny C. Pulse. July 2014

7 although it is not known how many of those obtaining a CGS actually go nor for how long. The annual career destination survey for doctors completing the foundation programme shows that 13 % were taking a career break and 10% were seeking appointments outside the UK, rather than go directly onto speciality training23, with the majority planning to return upon completion of their posts.

It is not known how many UK nurses work overseas, but in 2010, 6,357 nurses requested verification of their UK registration as part of the process of applying to work in another country24. However, there has been a marked decrease in the number of overseas nurses being recruited in the USA following a marked increase in the numbers of nurses being trained domestically25.

Factors identified as key drivers for health workers migrating include26:-

Better working conditions Better resourced health systems Career opportunities Higher pay Provision of CPD

There have been suggestions that the impact of austerity on public sector finances in the UK, including impact on salaries and continuing professional development funding, coupled with increased demands being made of the workforce will lead to more overseas migration of health professionals from the UK27, particularly amongst doctors28.

Conclusion

Health professionals will continue to enjoy high graduate employment levels as workforce planning only accounts for the NHS sector 29.

23 F2 Career Destination report 2015. The UK Foundation Programme Office. 2015

24 ‘A decisive decade. The UK nursing labour market review 2011.’Buchan J & Seccombe RCN Labour Market Review. 2011

25 Focus on Health Workforce Policies in OECD Countries. March 2016. www.oecd.org/health

26 Policy Brief: How can the migration of health service professionals be managed so as to reduce any negative effects on supply? Buchan J. 2008. WHO

27 ‘Ch3: Economic crisis in the EU: Impact on health workforce mobility’ Dussault G & Buchan J in Health Professional Mobility in a Changing Europe. Ed. Buchan J et al. WHO 2014

28 ’5,000 doctors a year considering leaving the UK to emigrate abroad’ Kenny C. Pulse. July 2014

29 ‘HEE commissioning and investment plan - 2016/17’ health Education England www.hee.nhs.uk

8 Whilst the NHS has traditionally been the universities’ main customer for their health graduates, the graduates themselves are now becoming customers as they will want value for money from their degree programmes and objective careers advice about job opportunities/career choices beyond those traditionally offered within the NHS.

Universities need to ensure that students have access to a comprehensive picture of employment opportunities across a wide range of sectors, with opportunities to gain additional skills and experiences to help them make decisions about possible pathways.

Universities have rich resources to call on from their existing alumni as well as their existing networks and relationships both at strategic level and at faculty/School level to help them develop these resources.

Recommendations

Recommendations Rationale Map the full range of employment To provide students with a detailed picture of options available to students employment options and routes into and qualifications required for each Identify skills and experiences To help students understand what additional skills they required to work in non-traditional may need to develop in order to successfully apply for roles/sectors (other than NHS) roles Encourage students to research their Encourage students to gain a broader picture of an potential employers. employer, and opportunities for career progression, and also its geographical location. Is it well connected, is accommodation readily available and affordable. Ie Signpost to online resources Employer websites Geographical location of employer Profession-specific recruitment websites Continue to develop/grow Develop more detailed networks and relationships to relationships with wide range of increase range of employment opportunities for students employers across Devon/Cornwall Ie biotech, pharma, R&D, independent care sector, both at Careers Service level and at charity sector, sport, opticians faculty level (sector/industry specific)

Consider opportunities for Give students more insight into working in non-NHS placements/work experience in wide roles, ie working alongside a physiotherapist in private range of employers practice Consider cross-faculty/School Develop new linkages initiatives that would enhance networks and create synergies for tie Incorporate entrepreneurship/ business management alternative career pathways, skills into curricula

Look to strengthen careers and Incorporate Careers activities into undergraduate employability initiatives more fully programmes/modules within Faculty and Schools encourage contribution of industry experts to learning programmes through sessional lecturing, guest lecturing and curriculum review;

Develop core units dedicated to employability skill development; use of e-portfolios to provide students with a tool to catalogue their development of professional competencies and employability skills; Develop and strengthen alumni Develop alumni networks across professions and

9 networks Increase number and range of employment sectors, and involve in careers activities to alumni across health professions, and provide students with detailed information about consider grouping into alternative career options. ‘employment/sector clusters’30 Create opportunities for alumni mentoring for students to gain understanding of role requirements/opportunities

Identify additional skills that would help students gain employment and signpost students to activities where they can develop these

Develop resources to signpost/ Health professionals are highly sought after by many identify overseas opportunities overseas countries available to health professionals:- -qualifications and experience required -areas to consider- language, culture, work environment -advice from professional bodies and regulators -experience of alumni that have worked overseas -key recruitment resources

Utilise existing School/Faculty staff national/international networks to help identify career opportunities nationally and internationally International opportunities for graduates 31

Paper prepared by: Sarah Watson-Fisher, September 2016

30 Plymouth Connect Development Project (Employability SIP Project)- Student Services, Plymouth University- June 2016

31 International Student Employability, Mobility and Industry Benchmarking Peer Review Workshop and Global Think Tank Summit. Final Report- Outcomes and Actions for Future Collaboration. Booth S & Read S, Univ of Tasmania. 2016

10