Pelyvás Péter Performativity Talk 5, 05.12.2013.

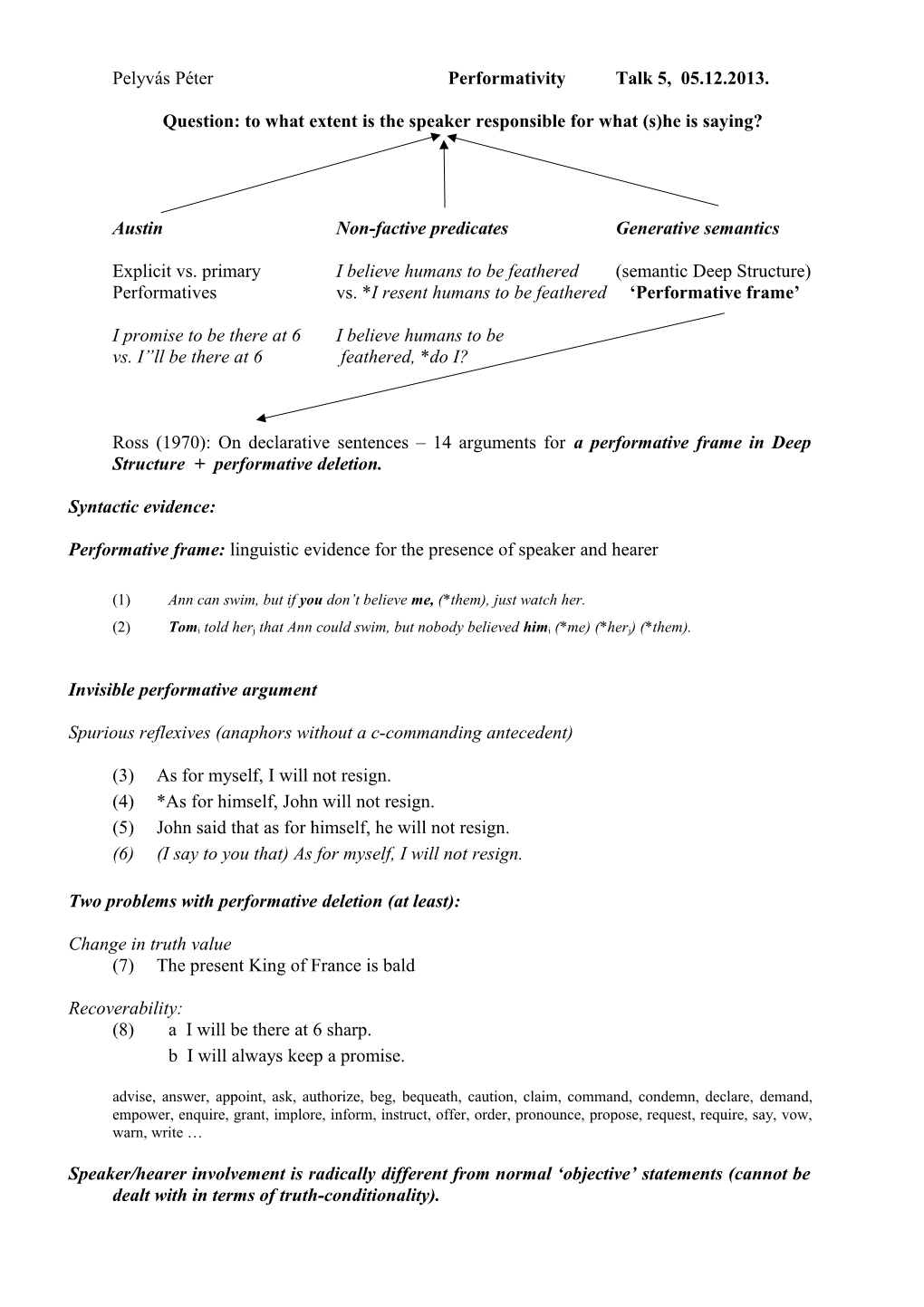

Question: to what extent is the speaker responsible for what (s)he is saying?

Austin Non-factive predicates Generative semantics

Explicit vs. primary I believe humans to be feathered (semantic Deep Structure) Performatives vs. *I resent humans to be feathered ‘Performative frame’

I promise to be there at 6 I believe humans to be vs. I”ll be there at 6 feathered, *do I?

Ross (1970): On declarative sentences – 14 arguments for a performative frame in Deep Structure + performative deletion.

Syntactic evidence:

Performative frame: linguistic evidence for the presence of speaker and hearer

(1) Ann can swim, but if you don’t believe me, (*them), just watch her.

(2) Tomi told herj that Ann could swim, but nobody believed himi (*me) (*herj) (*them).

Invisible performative argument

Spurious reflexives (anaphors without a c-commanding antecedent)

(3) As for myself, I will not resign. (4) *As for himself, John will not resign. (5) John said that as for himself, he will not resign. (6) (I say to you that) As for myself, I will not resign.

Two problems with performative deletion (at least):

Change in truth value (7) The present King of France is bald

Recoverability: (8) a I will be there at 6 sharp. b I will always keep a promise.

advise, answer, appoint, ask, authorize, beg, bequeath, caution, claim, command, condemn, declare, demand, empower, enquire, grant, implore, inform, instruct, offer, order, pronounce, propose, request, require, say, vow, warn, write …

Speaker/hearer involvement is radically different from normal ‘objective’ statements (cannot be dealt with in terms of truth-conditionality). ● In the eyes of those who believe in the strict separation of the language system and language use, this can be evidence that language use need not (should not?) be discussed in linguistic theory.

BUT: Can you describe the system without its use, in the light of (9) a I believe humans to be feathered vs. b *I resent humans to be feathered (10) a Who do you believe to be innocent? vs. b * Who do you resent to be innocent? (11) a That John is a genius is tragic. vs. b *That John is a genius is likely. (12) a John’s stupidity is obvious vs. b *John’s stupidity is likely. (13) a It is likely that tomorrow he will arrive / Tomorrow it is likely that he will arrive (+ Tomorrow he is likely to arrive) vs. b *It is tragic that tomorrow he will arrive / *Tomorrow it is tragic that he will arrive (+ *Tomorrow he is tragic to arrive). (14) a John thinks that Mary knows the truth, does he? vs. b *I think that Mary knows the truth, do I? etc.

●Those who hold the view that these phenomena are not at the periphery of the language system try to account for the irregularities of cognitive predicates by postulating that they have a special status: they are non-propositional:

Hare (1970): Meaning and Speech Acts

Non-propositional elements

Neustic Tropic Phrastic Epistemic commitment deontic value (propositional core) 0 I-say-so it-is-so m I-don`t-know so-be-it

0 = unmarked m = marked

(9) It is raining. (0, 0) (10) Is it raining? / It may be raining. (m, 0) (11) Let it rain! / It must rain (0, m) (12) Shall it rain? (m, m)

A direct precursor to the cognitive notion of epistemic grounding The cognitive view (Langacker, Ronald W. 2004. Remarks on Nominal Grounding)

A. On the clause level

Speaker/hearer involvement: Epistemic grounding

The cognitive notion of epistemic grounding relates (the linguistic expression of) a process or thing (a verb or a noun) to the situation of its use: speaker/hearer knowledge, and time and place of utterance. The latter are subsumed under the term ground.

An entity is epistemically grounded when its location is specified relative to the speaker and hearer and their spheres of knowledge.

For verbs, tense and mood ground an entity epistemically; for nouns, definite/indefinite specifications establish epistemic grounding.

Epistemic grounding distinguishes finite verbs and clauses from nonfinite ones, and nominals (noun phrases) from simple nouns. (Langacker 1987: 489)

Linguistic relevance (e.g.) → (epistemic) modality: John is/must be an idiot. (Subjectivity/Modality, 19th Dec.)

(13) I believe John to be a genius.

(14) *I regret John to be a genius.

B. On the NP level

Reference in discourse – Grounding on the level of the NP

(anchored to speaker/hearer knowledge, etc.)

When used felicitously, a nominal singles out and identifies the intended referent. But what precisely does this mean? How and in what sense does a nominal identify its referent?

… an expression’s semantic value is not exclusively based on objective properties of its referent, but further reflects a conventionally established way of conceiving and portraying it for linguistic purposes … For linguistic purposes … the referents of concern are discourse referents, which may or may not be identified with actual individuals in a real or imagined world. In discussing a given world (even the one we consider “real”), we routinely invoke and describe a diverse array of mental spaces

(PP: e.g. PATIENT in the doctor – patient relationship)

[some of which may be]

distinct from actuality, and since entities confined to those spaces are only virtual, we often have occasion to refer to virtual instances of a type. It must first be emphasized that a nominal does not identify its referent in absolute terms, but only for discourse purposes in a particular discourse context. This is clearly shown by the fact that nominal referents are often virtual. Consider the statement I don’t have a cat so I don’t have to feed it. The first clause establishes a virtual cat as a discourse referent,which the pronoun it refers to anaphorically. Since the cat is only virtual—“conjured up” just in order to specify what does not obtain in actuality—there is no point in asking which particular cat it might be, nor any way to identify it independently of the discourse context, for it only exists in the virtual situation invoked by the discourse for discourse purposes.

Yet the speaker and hearer both identify the intended referent of both nominals: it refers to a cat, and the cat in question is the fictive creature conjured up to describe a situation not characteristic of actuality.

The point however is general. Even when the referent is an actual individual, a nominal only identifies it in discourse terms, not in any absolute way. For example, the statement Joe has a daughter establishes an instance of daughter as a discourse referent and portrays her as an actual individual. She is identified for discourse purposes, for if the speaker continues by saying She’s very smart, the listener knows precisely who is said to be intelligent. Yet the listener has no way to identify this individual independently of the discourse. He knows nothing about her except that she is Joe’s daughter and is smart. If he passed her on the street, he would not know who she was.

(The point can even be made in regard to proper names, which supposedly refer uniquely to specific, actual individuals. … )

Langacker, Ronald W. 2004. Remarks on Nominal Grounding. Functions of Language 11:77-113, emphases are mine -- PP.

Foucault: “practices that systematically form the objects of which they speak” → B.T.