Geraldine Lester Perry V. West Virginia Division of Natural

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BARBOUR Audra State Park WV Dept. of Commerce $40,798 Barbour County Park Incl

BARBOUR Audra State Park WV Dept. of Commerce $40,798 Barbour County Park incl. Playground, Court & ADA Barbour County Commission $381,302 Philippi Municipal Swimming Pool City of Philippi $160,845 Dayton Park Bathhouse & Pavilions City of Philippi $100,000 BARBOUR County Total: $682,945 BERKELEY Lambert Park Berkeley County $334,700 Berkeley Heights Park Berkeley County $110,000 Coburn Field All Weather Track Berkeley County Board of Education $63,500 Martinsburg Park City of Martinsburg $40,000 War Memorial Park Mini Golf & Concession Stand City of Martinsburg $101,500 Faulkner Park Shelters City of Martinsburg $60,000 BERKELEY County Total: $709,700 BOONE Wharton Swimming Pool Boone County $96,700 Coal Valley Park Boone County $40,500 Boone County Parks Boone County $106,200 Boone County Ballfield Lighting Boone County $20,000 Julian Waterways Park & Ampitheater Boone County $393,607 Madison Pool City of Madison $40,500 Sylvester Town Park Town of Sylvester $100,000 Whitesville Pool Complex Town of Whitesville $162,500 BOONE County Total: $960,007 BRAXTON Burnsville Community Park Town of Burnsville $25,000 BRAXTON County Total: $25,000 BROOKE Brooke Hills Park Brooke County $878,642 Brooke Hills Park Pool Complex Brooke County $100,000 Follansbee Municipal Park City of Follansbee $37,068 Follansbee Pool Complex City of Follansbee $246,330 Parkview Playground City of Follansbee $12,702 Floyd Hotel Parklet City of Follansbee $12,372 Highland Hills Park City of Follansbee $70,498 Wellsburg Swimming Pool City of Wellsburg $115,468 Wellsburg Playground City of Wellsburg $31,204 12th Street Park City of Wellsburg $5,786 3rd Street Park Playground Village of Beech Bottom $66,000 Olgebay Park - Haller Shelter Restrooms Wheeling Park Commission $46,956 BROOKE County Total: $1,623,027 CABELL Huntington Trail and Playground Greater Huntington Park & Recreation $113,000 Ritter Park incl. -

GENERAL GUIDE to the WEST VIRGINIA STATE PARKS

Campground information Special events in the Parks A full calendar of events is planned across West Virginia at state Many state parks, forests and wildlife management areas offer SiteS u e parks. From packaged theme weekends, dances and workshops, to camping opportunities. There are four general types of campsites: Campground check-out time is noon, and only one tent or trailer is ecology, history, heritage, native foods, and flora and fauna events, permitted per site. A family camping group may have only one or two you’ll find affordable fun. DeLuxe: Outdoor grill, tent pad, pull-off for trailers, picnic table, additional tents on its campsite. Camping rates are based on groups electric hookups on all sites, some with water and/or sewer hookups, of six persons or fewer, and there is a charge for each additional Wintry months include New Year’s Eve and holiday rate packages dumping station and bathhouses with hot showers, flush toilets and person above six, not exceeding 10 individuals per site. at many of the lodge parks. Ski festivals, clinics and workshops for laundry facilities. Nordic and alpine skiers are winter features at canaan valley resort All campers must vacate park campsites for a period of 48 hours after and blackwater Falls state parks. north bend’s Winter Wonder StanDarD: Same features as deluxe, with electric only available at 14 consecutive nights camping. The maximum length of stay is 14 Weekend in January includes sled rides, hikes, fireside games and some sites at some areas. Most sites do not have hookups. consecutive nights. n ature & recreation Programs indoor and outdoor sports. -

The Following Documentation Is an Electronically- Submitted Vendor

The following documentation is an electronically‐ submitted vendor response to an advertised solicitation from the West Virginia Purchasing Bulletin within the Vendor Self‐Service portal at wvOASIS.gov. As part of the State of West Virginia’s procurement process, and to maintain the transparency of the bid‐opening process, this documentation submitted online is publicly posted by the West Virginia Purchasing Division at WVPurchasing.gov with any other vendor responses to this solicitation submitted to the Purchasing Division in hard copy format. Purchasing Division State of West Virginia 2019 Washington Street East Solicitation Response Post Office Box 50130 Charleston, WV 25305-0130 Proc Folder : 146150 Solicitation Description : Addendum; A&E-Campground Improvements Beech Fork/Pipestem Proc Type : Central Contract - Fixed Amt Date issued Solicitation Closes Solicitation No Version 2015-11-18 SR 0310 ESR11181500000002323 1 13:30:00 VENDOR 000000203864 S & S ENGINEERS INC FOR INFORMATION CONTACT THE BUYER Guy Nisbet (304) 558-2596 [email protected] Signature X FEIN # DATE All offers subject to all terms and conditions contained in this solicitation Page : 1 FORM ID : WV-PRC-SR-001 Line Comm Ln Desc Qty Unit Issue Unit Price Ln Total Or Contract Amount 1 Architectural engineering Comm Code Manufacturer Specification Model # 81101508 Extended Description : AE Services Pipestem and Beech Fork Campground improvements. Page : 2 WEST VIRGINIA DIVISION OF NATURAL RESOURCES PARKS & RECREATION 324 FOURTH AVENUE SOUTH CHARLESTON, WV 25303 PROPOSAL FOR PIPESTEM RESORT STATE PARK & BEECH FORK STATE PARK CAMPGROUND IMPROVEMENTS PROJECT NOVEMBER 2015 S & S ENGINEERS, INC. 501 EAGLE MOUNTAIN ROAD CHARLESTON, WV 25311 (304) 342-7168 (304) 342-7169 (FAX) WWW.S-S-ENG.COM WEST VIRGINIA DIVISION OF NATURAL RESOURCES PARKS & RECREATION PIPESTEM RESORT STATE PARK & BEECH FORK STATE PARK CAMPGROUND IMPROVEMENTS PROJECT ~TABLE OF CONTENTS ~ SCOPE OF SERVICES ....................................................... -

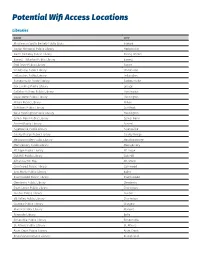

Potential Wifi Access Locations

Potential Wifi Access Locations Libraries NAME CITY Mussleman South Berkely Public Libra Inwood Naylor Memorial Public Library Hedgesville North Berkeley Public Library Falling Waters Barrett - Wharton Public Library Barrett Coal River Public Library Racine Whitesville Public Library Whitesville Follansbee Public Library Follansbee Barboursville Public Library Barboursville Cox Landing Public Library Lesage Gallaher Villiage Public Library Huntington Guyandotte Public Library Huntington Milton Public Library Milton Salt Rock Public Library Salt Rock West Huntington Public Library Huntington Center Point Public Library Center Point Ansted Public Library Ansted Fayetteville Public Library Fayetteville Gauley Bridge Public Library Gauley Bridge Meadow Bridge Public Library Meadow Bridge Montgomery Public Library Montgomery Mt Hope Public Library Mt. Hope Oak Hill Public Library Oak Hill Allegheny Mt. Top Mt. Storm Quintwood Public Library Quinwood East Hardy Public Library Baker Ravenswood Public Library Ravenswood Clendenin Public Library Clendenin Cross Lanes Public Library Charleston Dunbar Public Library Dunbar Elk Valley Public Library Charleston Glasgow Public Library Glasgow Marmet Public Library Marmet Riverside Library Belle Sissonville Public Library Sissonsville St. Albans Public Library St. Albans Alum Creek Public Library Alum Creek Branchland Outpost Library Branchland NAME CITY Fairview Public Library Fairview Mannington Public Library Mannington Benwood McMechen Public Library McMechen Cameron Public Library Cameron Sand Hill -

Development of Outdoor Recreation Resource Amenity Indices for West Virginia

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2008 Development of outdoor recreation resource amenity indices for West Virginia Jing Wang West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Wang, Jing, "Development of outdoor recreation resource amenity indices for West Virginia" (2008). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 2680. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/2680 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Development of Outdoor Recreation Resource Amenity Indices for West Virginia Jing Wang Thesis submitted to the Davis College of Agriculture, Forestry, and Consumer Sciences At West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Recreation, Parks, and Tourism Resources Jinyang Deng, Ph.D., Chair Chad -

2019 ASD Summer Activities Guide

1 This list of possible summer activities for families was developed to generate some ideas for summer fun and inclusion. Activities on the list do not imply any endorsement by the West Virginia Autism Training Center. Many activities listed are low cost or no cost. Remember to check your local libraries, YMCA, and Boys and Girls Clubs; they usually have fun summer activities planned for all ages. North Bend Rail Trail goes through numerous counties and can offer hours of fun outdoor time with various activities. At the bottom of this document are county extension offices. You may contact them for information for Clover buds, 4-H, Energy Express, Youth Volunteers and other activities that they host throughout WV. Link for their website: https://extension.wvu.edu/ County List and Information in Alphabetical Order Barbour County • WV Blue and Gray Trail; First Land Battle of Civil War http://www.blueandgrayreunion.org • Phillipi Covered Bridge & Museum Route 250, Phillipi, WV • Adaland Mansion www.adaland.org • Barbour County Historical Museum Mummies https://bestthingswv.com/unusual-attractions/ Berkeley County • Circa Blue Fest, June 7-9 http://www.circabluefest.com/ • Wonderment Puppet Theater Martinsburg 412 W King St 304-260-9382 • For The Kids By Geopre Children’s Museum Martinsburg 229 E. Martin St. 304-264-9977 • Galaxy Skateland Martinsburg 1201 3rd St. 304-263-0369 2 • JayDee’s Family Fun Center (304) 229-4343 Boone County • Upper Big Branch Miners Memorial http://www.ubbminersmemorial.com/ • Waterways https://www.facebook.com/waterwayswv • Coal River Festival (304) 419-4417 • Boone County Heritage & Arts Center Madison, WV http://www.boonecountywv.org/PDF/Boone-Heritage-and-Arts-Center.pdf Braxton County • Burnsville Dam/ Recreational Area https://www.recreation.gov/camping/gateways/315 • Sutton Lake https://www.suttonlakemarina.com/about-sutton-lake • Falls Mill https://www.facebook.com/pages/category/Community/Falls-Mill-West-Virginia- 144887218858429/ • Bulltown Historic Area 304-853-2371 • Monster Museum, 208 Main St. -

Guide to Accessible Recreation in West Virginia (PDF)

West Virginia Assistive Technology System Alternate formats are available. Please call 800-841-8436 Contents INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................... 10 HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE............................................................................................................................ 10 TRAVELING IN WEST VIRGINIA .................................................................................................................... 12 Getting Around ....................................................................................................................................... 12 Trip Tips ................................................................................................................................................... 12 211 .......................................................................................................................................................... 12 Travel Information .................................................................................................................................. 12 CAMC Para-athletic Program .................................................................................................................. 13 Challenged Athletes of West Virginia ..................................................................................................... 13 West Virginia Hunter Education Association ......................................................................................... -

Fishing Brochure

Just a few of the experiences that await anglers Wildlife Resources Offices in the Mountain State. District 1 Barbour, Brooke, Hancock, Harrison, Marion, Marshall, Monongalia, Ohio, Preston, Taylor, Tucker, and Wetzel counties Farmington WV (304) 825-6787 “Daddy, I caught one! I caught one!” shouted District 2 Berkeley, Grant, Hampshire, Hardy, Jefferson, Mineral, the little girl as she furiously reeled in the Morgan, and Pendleton counties stubborn fish hooked on the end of her line. Romney, WV (304) 822-3551 She proudly held up the wriggling sunfish District 3 Braxton, Clay, Lewis, Nicholas, Pocahontas, Randolph, for everyone at the small lake to admire. Upshur, and Webster counties WV State Wildlife Center (304) 924-6211 District 4 Fayette, Greenbrier, McDowell, Mercer, Monroe, Raleigh, Summers, and Wyoming counties The silence of the morning was suddenly Beckley, WV (304) 256-6947 broken when a fisherman set the hook, and District 5 Boone, Cabell, Kanawha, Lincoln, Logan, Mason, Mingo, a large fish surfaced near a submerged log. Putnam, and Wayne counties After a battle of several minutes, the McClintic WMA (304) 675-0871 fisherman eased the fish alongside the boat District 6 Calhoun, Doddridge, Gilmer, Jackson, Pleasants, Ritchie, and carefully released the musky to Roane, Tyler, Wirt, and Wood counties Parkersburg, WV (304) 420-4550 challenge another angler on another day. Elkins Operations Center (304) 637-0245 It was early evening and the fisherman made one last cast in the long pool of the cold mountain stream. The fly settled onto the water and quickly disappeared as the brook trout rose and darted upstream. -

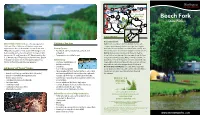

Beech Fork State Park

OH 7 2Exit 18 Exit 15 23 Huntington 64 Milton Exit60 11 60 52 ALT Barboursville Exit 8 10 64 WV 10 Melissa Beech Fork 75 State Park Beech Fork 152 Salt Rock 52 Lavalette 10 KY Corps of Engineers State Park Cyrus Dam & Recreation Area West Beech Fork Lake Hamlin3 23 Wildlife Management Area Prichard Wayne 10 LOCATION From Interstate 64: BE E ch Fork StatE Park was officially opened in ThN O I gs T dO Exit 11 (Hal Greer Blvd. Exit), take state Route 10 South. 1979 and offers 3,144 acres of the best recreation Continue approximately 4 miles. Turn right onto Hughes experience in the southwestern section of the state. Game courts Branch Road and follow it to the end (another 4 miles). Turn The park is located 12 miles south of Huntington and • Basketball, tennis, horseshoes, softball and left and the park is about 2 miles straight ahead (30 minutes). Barboursville and a short drive from Charleston, WV, volleyball Exit 18 (Barboursville Exit), take U.S. Route 60 West for Cincinnati, OH, and Lexington, KY. Developed by the • Equipment is available for rent about 2 miles. Turn left onto Alternate state Route 10 South U. S. Army Corps of Engineers in the mid-1970s, Beech and go about 3 miles to state Route 10 North. Continue on Fork Lake is popular for recreational boating, bass Swimming state Route 10 North for less than a mile then turn left onto fishing and wildlife watching experiences. • 50-meter swimming pool Hughes Branch Road and follow it to the end. -

Departmental, Statistical & General Information

Section Eleven Departmental, Statistical & General Information National Symbols Legal Holidays State Symbols Hospitals Statistical Summary Libraries Aeronautics Mines & Mining Census Data Oil & Gas Geographical Parks & Forests Highways Taxation & Finance 1044 WEST VIRGINIA BLUE BOOK NATIONAL SYMBOLS The American Flag The flag of the United States has 13 horizontal stripes, seven red and six white-the red and white stripes alternating, and a union which consists of white stars of five points on a blue field placed in the upper quarter next to the staff and extending to the lower edge of the fourth red stripe from the top. The number of stars is the same as the number of states in the union. The canton or union now contains 50 stars. On the admission of a state into the union, a star will be added to the union of the flag and such addition will take effect on the fourth day of July next succeeding such admission. Pledge of Allegiance I pledge allegiance to the flag of the United States of America and to the republic for which it stands, one nation under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all. OFFICIAL STATE SYMBOLS State Flag Before the design of the present state flag was officially adopted by the Legislature on March 7, 1929, by Senate Joint Resolution No. 18, West Virginia had been represented by several flags which proved impractical. Prominently displayed on the pure white field of today’s flag and emblazoned in proper colors is the coat of arms, the lower half of which is wreathed by rhododendron. -

Performance Review Division of Natural Resources the Park System

September 2018 PE 18-07-613 PERFORMANCE REVIEW DIVISION OF NATURAL RESOURCES THE PARK SYSTEM AUDIT OVERVIEW The West Virginia Park System Continues to Lack the Necessary Resources to Adequately Reduce the Number of Deferred Maintenance and Capital Improvement Projects. WEST VIRGINIA LEGISLATIVE AUDITOR PERFORMANCE EVALUATION & RESEARCH DIVISION JOINT COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT OPERATIONS Senate House of Delegates Agency/ Citizen Members Ed Gaunch, Chair Gary G. Howell, Chair Keith Rakes Mark Maynard, Vice-Chair Danny Hamrick Vacancy Ryan Weld Zack Maynard Vacancy Glenn Jeffries Richard Iaquinta Vacancy Corey Palumbo Isaac Sponaugle Vacancy JOINT COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT ORGANIZATION Senate House of Delegates Ed Gaunch, Chair Gary G. Howell, Chair Tony Paynter Mark Maynard, Vice-Chair Danny Hamrick, Vice-Chair Terri Funk Sypolt Greg Boso Michael T. Ferro, Minority Chair Guy Ward Charles Clements Phillip W. Diserio, Minority Vice-Chair Scott Brewer Mike Maroney Chanda Adkins Mike Caputo Randy Smith Dianna Graves Jeff Eldridge Dave Sypolt Jordan C. Hill Richard Iaquinta Tom Takubo Rolland Jennings Dana Lynch Ryan Weld Daniel Linville Justin Marcum Stephen Baldwin Sharon Malcolm Rodney Pyles Douglas E. Facemire Patrick S. Martin John Williams Glenn Jeffries Zack Maynard Corey Palumbo Pat McGeehan Mike Woelfel Jeffrey Pack WEST VIRGINIA LEGISLATIVE AUDITOR PERFORMANCE EVALUATION & RESEARCH DIVISION Building 1, Room W-314 State Capitol Complex Charleston, West Virginia 25305 (304) 347-4890 Aaron Allred John Sylvia Brandon Burton Keith Brown Noah Browning Legislative Auditor Director Research Manager Senior Research Analyst Referencer Note: On Monday, February 6, 2017, the Legislative Manager/Legislative Audi- tor’s wife, Elizabeth Summit, began employment as the Governor’s Deputy Chief Counsel. -

Exploring West Virginia's Parks and Forests

e-WV Lesson Plan Exploring West Virginia’s Parks and Forests Objective: Students will learn about the state’s parks and forests by designing a travel brochure. GRADE LEVEL Fourth Grade TIME REQUIRED 90 minutes over two days ASSESSMENT A rubric is provided for assessment. MATERIALS NEEDED e-WV Paper/pencil Glue Colored pencils Markers Crayons Scissors White paper Variety of different travel guides for examples IMPORTANT ARTICLES RELATED TO STATE PARKS AND FORESTS State Parks: www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/569 State Forests: www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/568 Tourism: www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/750 Audra State Park: www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/311 Babcock State Park: www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/321 Beartown State Park: www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/411 Beech Fork State Park: www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/430 Berkeley Springs State Park: www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/460 Blackwater Falls State Park: www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/521 Blennerhassett Island State Park: www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/540 Bluestone State Park: www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/579 Cabwaylingo State Forest: www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/803 Cacapon State Park: www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/807 e-WV: The West Virginia Encyclopedia Page 1 Calvin W. Price State Forest: www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/811 Camp Creek State Park: www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/824 Canaan Valley State Park: www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/911 Carnifex Ferry Battlefield State Park: www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/972 Cass Scenic Railroad State Park: www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/997