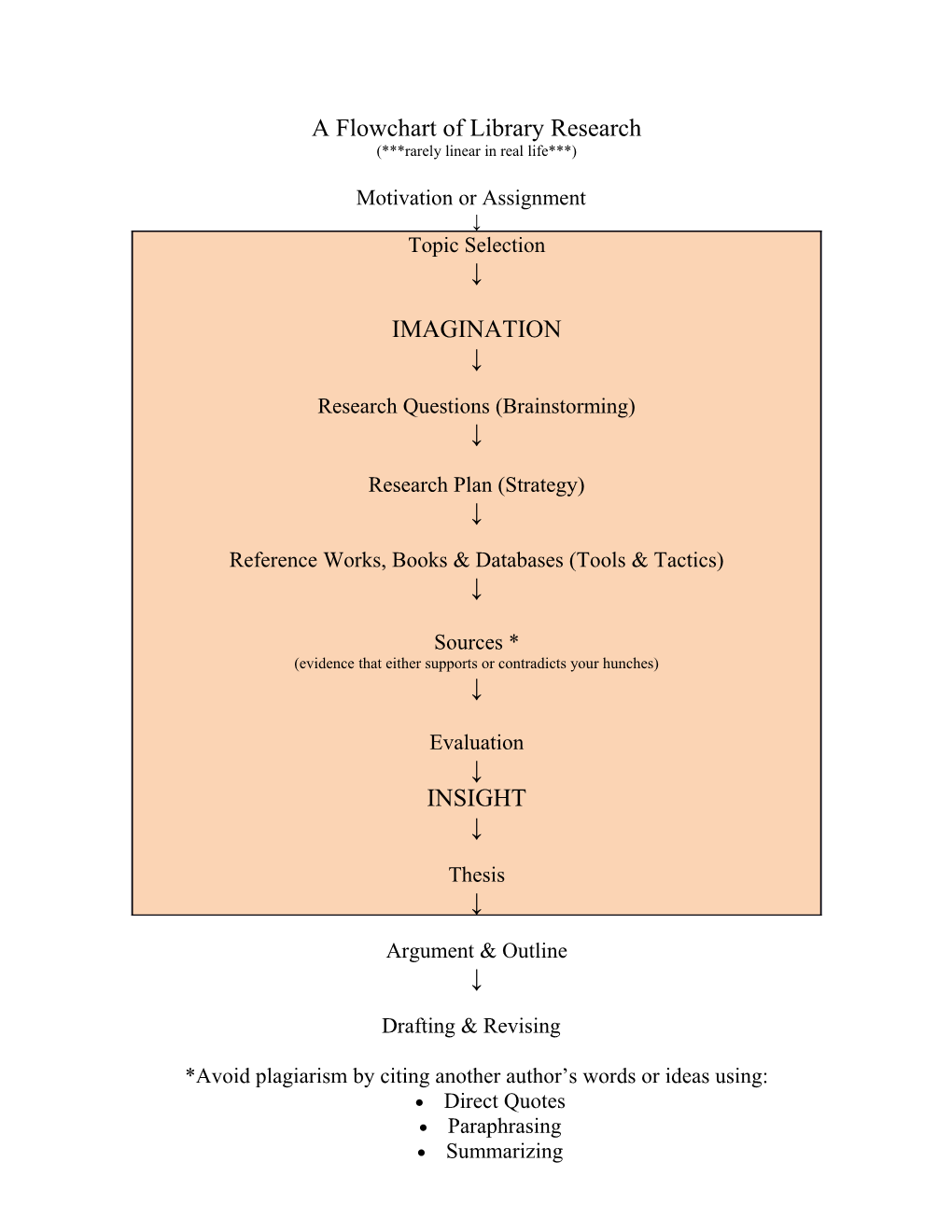

A Flowchart of Library Research (***rarely linear in real life***)

Motivation or Assignment ↓ Topic Selection ↓

IMAGINATION ↓

Research Questions (Brainstorming) ↓

Research Plan (Strategy) ↓

Reference Works, Books & Databases (Tools & Tactics) ↓

Sources * (evidence that either supports or contradicts your hunches) ↓

Evaluation ↓ INSIGHT ↓

Thesis ↓

Argument & Outline ↓

Drafting & Revising

*Avoid plagiarism by citing another author’s words or ideas using: Direct Quotes Paraphrasing Summarizing English 90/Library Workshop

Why are imagination and insight important in the research process?

You must allow time, starting early in the process, to consider your work from all angles, to speculate, ponder and dream about it. That is what is meant by imagination: when the conscious mind buddies up with the unconscious mind to help solve a research problem. You cannot force imagination to kick in, but you can schedule time for reflection that is likely to promote it.

As researchers, you can never predict when in the process you have have what is widely called the “Aha!” moment, the intuitive instant when you see a solution to your investigation. We’ve put insight between the evaluation and the thesis steps because that’s it is often experienced, but it can come at any point.

One more point about the flowchart: it’s rarely linear in real life. Typically some of the stages will overlap, and seasoned researchers will tell you that occasionally they step aside to explore another angle, pause briefly, or even double back to a previous point. It might help to envision the process as a spiral ramp, or as a flexible chain of elastic links where the whole can expand or contract or loop around itself, depending on the complexity of the inquiry and the energy you apply to it.

Vocabulary

Librarian – College and university librarians have at least one graduate degree: a master’s in information science from a university. Most librarians on a 4-year campus will also have other advanced degree as well, so you may confer with an economics librarian who has an MBA or a life sciences librarian who has an MS in biochemistry or some other science.

Source - the evidence that supplies at least a partial answer to your inquiry. Every source must be evaluated by you in light of other sources and your own insights. You can evaluate any source (print or digital) based on the CRAP test (see attachment).

Tool - anything that either encapsulates common knowledge or points you to a source. Here are some examples:

o the Library’s SNAP online catalog indicates what books and other materials you will find in the collection.

o An encyclopedia article summarizes informaton on a topic and offers a few good sources in a list of further readings.

o An online database article that goes into depth on your topic.

Think of a tool as the appropriate utensil for the job at hand.

The logic of the library research process is the movement from what exists to what is worth using.

→

How do you decide on a topic?

Choose something that interests you and Read. Read. Read to get background on the topic. You can read summaries of the general area or issue your assignment covers in an encyclopedia or textbook. Feel free to start with Google or Wikipedia, but don’t stop there! Check out the references at the end of a Wikipedia article. Look at a general encyclopedia like World Book, or an electronic encyclopedia like Britannica or a subject- specific encyclopedia. You can ask a reference librarian for help in locating these.

On Plagiarism

Jump-start your research by taking notes from reference works, articles and books (or textbooks), websites, etc.

Front of 3x5 card

“The U.S. Navy played a vital role in the Normandy landings. The Navy was instrumental in getting the troops and equipment from America to England, and then across the Channel to the Normandy Beach.”

The key tactic to avoid plagiarism is to use quotation marks to indicate that you are transcribing someone else’s words verbatim.

Back of 3x5 card template for print source:

Author’s name Title of the specific entry in the encyclopedia or chapter in a book (or textbook) Title of encyclopedia or textbook as a whole City of publication, publisher’s name, year of publication Page(s) from which you copied or summarized text.

So, it looks like this:

Gawne, Jonathon “Lower All Landing Craft” Spearheading D-Day Santa Barbara, CA, ABC- CLIO, 2011 40-41

When you paraphrase or summarize information, you put it into your own words. Be aware, however, that neither the ideas nor their expression are your own! Give credit to the original author:

When you write the information onto a card, note whether it is a paraphrase or summary! paraphrase

During World War II, the U.S.Navy played a central role in moving troops along with their equipment and supplies across the Atlantic. Once in England, it was an easy trip to the Normandy Beach via the English Channel.

Gawne, Jonathon “Lower All Landing Craft” Spearheading D-Day Santa Barbara, CA, ABC- CLIO, 2011 40-41

For more help in using direct quotes, paraphrasing or summarizing, see the following PowerPoint: http://www.napavalley.edu/Library/Pages/WritingandCiting.aspx

Scroll down on the page to view: How to Incorporate Other Writer’s Work into Your Own. Sources & their Evaluation

Where can I find good sources of information for my research?

@NVC library of course!

Reference books Circulating books Online database articles (periodicals and scholarly articles)

At the start of the library research process, as you gather background information on your chosen topic, brainstorm about it, and begin to discover and review sources, it is your initial idea – expressed as a research question – that keeps you moving forward. It’s too soon to know where your inquiry will lead, so you will need patience.

Provided you keep working and thinking, you will have an unpredictable flash of insight that will transform how you view your topic. Your interesting, but probably vague notion will suddenly become the gem of a compelling, supportable and clear argument!

Evaluating Your Sources

The unexamined life is not worth living, said Socrates (in Plato, Apology 28a). So too, the unexamined source is not worth finding! When it comes to the library research process, this means you need to judge tools and sources as you go and expect to modify your thoughts, your subsequent steps, and sometimes even your research question based on your judgements.

Ready for Your Thesis?

Only after your insight can you write a thesis, one true sentence that explains your insight and that you can craft into an argument.

Here’s a few examples of a thesis statement: The Normandy Invasion was the key strategic move that led the German Army to retreat out of France. Had it not occurred, the the German Army would have taken Paris and could have conceivably won the war against the allies.

Or:

The coming of the railroads tranformed the everyday experience of people: instead of being confined by the limits of the horse, it expanded people’s notions of distance, time and even height! Insight feels terrific; it is a good feeling to recognize how your research question can be answered convincingly using sources.

Writing Your Paper

For some helpful tips on writing a research paper, check out:

Writing a Research Paper in 15 Easy Steps at: http://www.napavalley.edu/Library/Pages/WritingandCiting.aspx