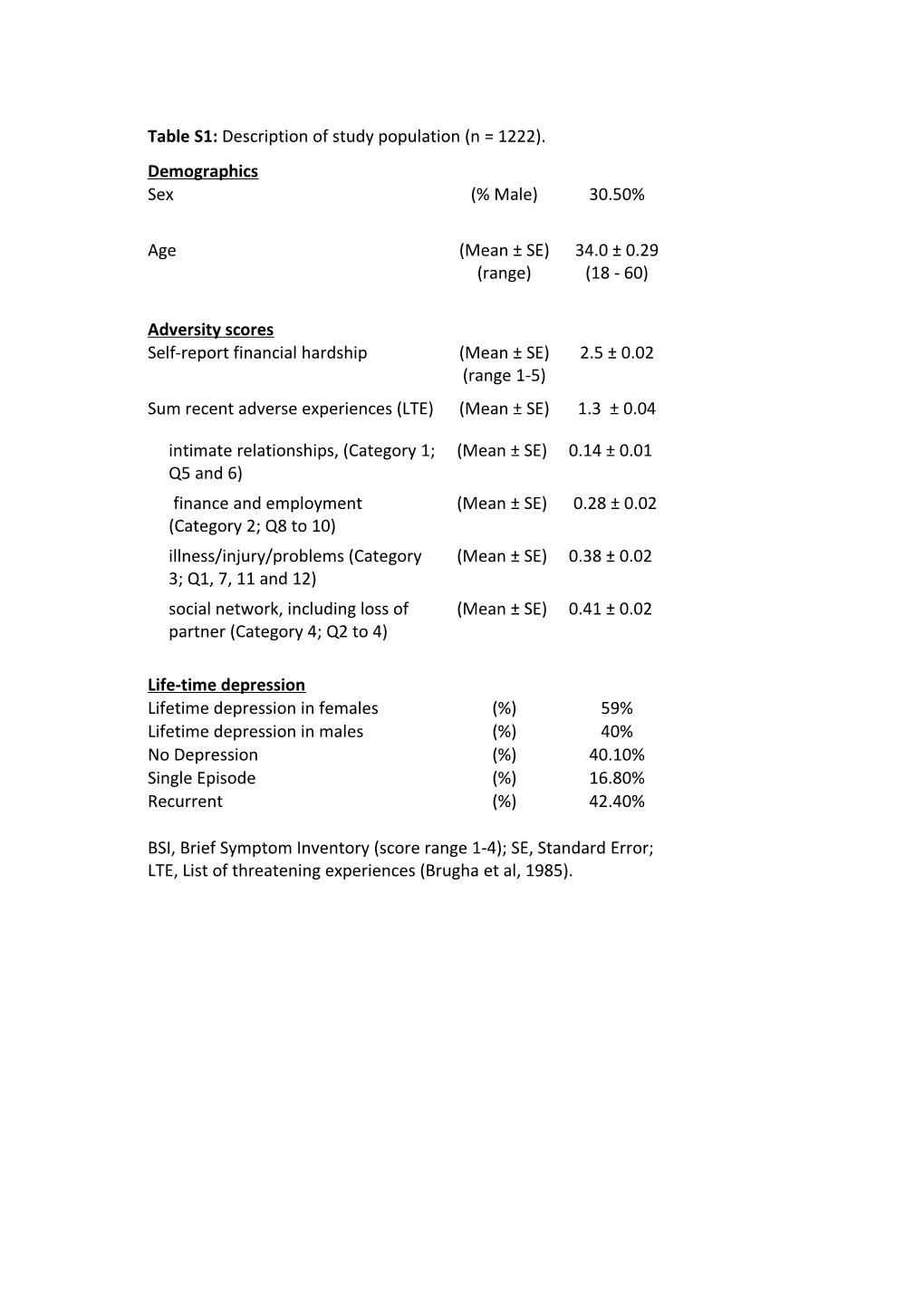

Table S1: Description of study population (n = 1222). Demographics Sex (% Male) 30.50%

Age (Mean ± SE) 34.0 ± 0.29 (range) (18 - 60)

Adversity scores Self-report financial hardship (Mean ± SE) 2.5 ± 0.02 (range 1-5) Sum recent adverse experiences (LTE) (Mean ± SE) 1.3 ± 0.04

intimate relationships, (Category 1; (Mean ± SE) 0.14 ± 0.01 Q5 and 6) finance and employment (Mean ± SE) 0.28 ± 0.02 (Category 2; Q8 to 10) illness/injury/problems (Category (Mean ± SE) 0.38 ± 0.02 3; Q1, 7, 11 and 12) social network, including loss of (Mean ± SE) 0.41 ± 0.02 partner (Category 4; Q2 to 4)

Life-time depression Lifetime depression in females (%) 59% Lifetime depression in males (%) 40% No Depression (%) 40.10% Single Episode (%) 16.80% Recurrent (%) 42.40%

BSI, Brief Symptom Inventory (score range 1-4); SE, Standard Error; LTE, List of threatening experiences (Brugha et al, 1985). Table S2: Haplotype analysis of current depression Genotype * Financial Hardship Genotype * Recent LTE score Haplotype Z-value p-value p-valueFDR Z-value p-value p-valueFDR 1 4.17 3.0E-05 1.3E-04 ** 3.50 4.6E-04 1.0E-03 ** 2 -3.23 1.2E-03 1.8E-03 ** -1.15 2.5E-01 1.9E-01 3 -0.02 9.8E-01 4.4E-01 -0.76 4.5E-01 2.9E-01 4 -1.32 1.9E-01 1.9E-01 -0.42 6.7E-01 3.3E-01 5 -1.13 2.6E-01 1.9E-01 -0.65 5.2E-01 2.9E-01 Current depression is measured using the brief symptom inventory (BSI) depression subscale and all calculations include age and sex as covariates, and use an additive model. Haplotype composition can be found in Figure 2. p-valueFDR, False discovery rate significance value; *, p-valueFDR between 0.05 and 0.005; **, p-valueFDR < 0.005. Table S3: Single SNP analysis of current depression score by sex Male (n = 373) Female (n = 849) Marker Model Z-value p-value Z-value p-value rs41279104 Add 0.75 4.5E-01 0.46 6.5E-01 Dom 0.73 4.7E-01 0.96 3.4E-01 rs4767533 Add 1.06 2.9E-01 -1.62 1.1E-01 Dom 0.54 5.9E-01 -1.51 1.3E-01 rs693534 Add 1.41 1.6E-01 3.21 1.3E-03 ** Dom 0.93 3.5E-01 2.38 1.7E-02 * rs527590 Add 1.07 2.9E-01 -0.26 8.0E-01 Dom 0.59 5.5E-01 0.22 8.3E-01 rs10507279 Add -3.00 2.7E-03 * -3.30 9.6E-04 ** Dom -3.30 9.6E-04 * -2.96 3.1E-03 ** rs1004356 Add -2.40 1.6E-02 * -3.30 9.6E-04 ** Dom -2.65 8.0E-03 * -2.96 3.1E-03 ** rs579604 Add 1.54 1.2E-01 -0.87 3.8E-01 Dom 1.33 1.8E-01 -0.55 5.8E-01 rs3782218 Add -2.72 6.6E-03 * -3.06 2.2E-03 ** Dom -2.98 2.9E-03 * -2.65 8.0E-03 * rs816296 Add 1.32 1.9E-01 -1.14 2.5E-01 Dom 0.94 3.5E-01 -1.32 1.9E-01 rs9658281 Add -2.37 1.8E-02 * -2.48 1.3E-02 * Dom -2.62 8.9E-03 * -2.60 9.5E-03 * rs1520810 Add 1.39 1.6E-01 -1.44 1.5E-01 Dom 1.04 3.0E-01 -1.61 1.1E-01 rs561712 Add 1.65 9.8E-02 4.18 2.9E-05 ** Dom 1.11 2.7E-01 2.94 3.3E-03 ** rs522910 Add -0.28 7.8E-01 -4.26 2.1E-05 ** Dom -0.64 5.2E-01 -4.01 6.1E-05 ** rs3782202 Add 1.22 2.2E-01 -2.69 7.1E-03 * Dom 1.08 2.8E-01 -2.24 2.5E-02 * rs2293050 Add -2.06 3.9E-02 * -2.66 7.9E-03 * Dom -1.76 7.9E-02 -2.86 4.2E-03 * rs816357 Add -0.64 5.2E-01 -0.95 3.4E-01 Dom -0.64 5.2E-01 -1.13 2.6E-01 rs7959232 Add -0.33 7.4E-01 -1.18 2.4E-01 Dom -0.80 4.2E-01 -1.23 2.2E-01 rs1875140 Add -0.55 5.8E-01 -1.33 1.8E-01 Dom -1.20 2.3E-01 -1.60 1.1E-01 Current depression is measured using the brief symptom inventory (BSI) depression subscale and all calculations include age as covariates. Add, Additive model; Dom, Dominant model (minor homozygotes grouped with heterozygotes); *, p-value between 0.05 and 0.005; **, p-value < 0.005. Figure S1: Schematic of the pair-wise LD (D’) for this study cohort, with extremely low MAF SNPs (<5%) excluded. The SNP included in the regional haplotypes are indicated by a black line. Figure S2: Comparison of the impact of haplotype on current depression score with increasing financial hardship. All haplotype combinations with a frequency over 5% (1/1, 1/2, 1/3 and 1/4) are shown. Carriers of 2 copies of haplotype 1 showed the most increase in depressive symptoms as financial hardship increased and carriers of 1 copy of haplotype 1 and 1 copy of haplotype 2 (1/2) showed the least increase despite the highest initial score. The financial hardship score is condensed with questionnaire scores 1 and 2 = 1, score 3 = 2, and scores 4 and 5 = 3. A key to the haplotype numeric codes can be found in figure 2. The numbers in each subgroups according to financial instability level and haplotype combination are as follows; 1/1: 1 = 59, 2 = 28, 3 = 9; 1/2: 1 =47, 2 = 28, 3 =7; 1/3: 1 = 46, 2 = 33, 3 = 14; 1/4: 1 = 42, 2 = 27, 3 = 12. The graph contains standard error (SE) bars. Supplemental Materials and Methods

Study design

Assesment of the population cohort was split into 2 levels. Level 1 used self-rating questionnaires, the accuracy of the self-rating questionnaire was then validated in

Level 2 participants which also had a face-to-to interview with a trained researcher.

Level-1 questionnaires

The Level-1 Questionnaire Booklet contained a Background Questionnaire (BGR) that was adapted from a version developed by the Epidemiology Unit of the

University of Manchester (Hunt et al, 1999) and was used in two previous studies

(Lazary et al, 2008, Juhasz et al, 2009). This well-structured self-rating questionnaire contained 22 items and collected information about age, sex, ethnicity, socio-economic background, personal medical history and family psychiatric history. Reported lifetime depression was derived from this questionnaire using 6 questions relating to personal psychiatric disorder history: 1.

Have you ever had emotional or psychiatric problem? 2. If yes, was it depression?

3. Have you ever had professional help for it? 4. Have you sought or needed help for depression in the last year? 5. If you have ever suffered from depression, how many times has this happened in your life? 6. Have you ever had any medication/treatment because of depression? The self-reported lifetime depression rates seen in this population are higher than rates previously reported in the UK biobank population samples, which used similar self-report methods with 16.8% vs 6.4% reporting single episodes and 42.4% vs 19.4% recurrent (Smith et al,

2013) (Table S1). As the cohort was recruited to study mood disorders enrichment for depression is not unexpected due to self-selection by those with either experience or interest in depression. The derived BGR lifetime depression category was further validated in the Level-2 interview phase of this study (see below).

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) was an exclusion criteria as these subjects were more likely to report depression (or score higher on the depression scale) secondarily to OCD, which has non-shared familial risk with major depressive disorder (MDD) (Bartz et al, 2006, Fineberg et al, 2007).

Other anxiety disorders were not exclusion criteria as they share a high proportion of genetic risk factors with MDD (Hettema et al, 2008). Subjects with reported manic or hypomanic episodes or psychotic disorder were also excluded.

Current depressive symptoms were measured using the 53-item Brief

Symptom Inventory (BSI) (Derogatis, 1993). The BSI is a 53-item self-report symptom inventory was developed to be an acceptable short alternative of the

SCL-90-R and is designed to reflect the psychological symptom patterns of psychiatric and medical patients and non-patients. This inventory reports profiles of nine primary symptom dimensions and three global indices of distress, including a depression subscale, which was used as the primary outcome measure in this study. Both test--retest and internal consistency reliabilities are shown to be very good for the primary symptom dimensions of the BSI, and it correlates well with the comparable dimensions of the Symptom Checklist-90-R (SCL-90-R;

Derogatis and Savitz, 2000). Participants are asked to rate how much specific symptoms have distressed or bothered them during the last week, using a 0 to 4 scale, which runs from ‘not at all’ to ‘extremely’, which when summed produced a continues variable for each symptom dimension.

A continuous weighted dimension score (sum of item scores on the dimension divided by the number of items completed) of depression was calculated and used in an analysis similar to that we have reported previously (Juhasz et al, 2009,

Juhasz et al, 2011). As would be expected in a population sample the BSI depression score has a non-normal distribution with 19% of participants reporting no depressive symptoms. The List of Life Threatening Experiences (LTE) was used to measure negative life events occurring in the last year related to intimate relationships, financial difficulties, illnesses/injuries and network problems (Brugha et al, 1985).

The sum of life event items was used in the analysis. Previously we reported a 5-

HTTLPR x stressful life events interaction (Lazary et al, 2008) and a cannabinoid receptor 1 gene CNR1 x stressful life events interaction (Juhasz et al, 2009) using this questionnaire. Current financial hardship was assessed using a self-report 5- point scale (1 = living very comfortably, 2 = living quite comfortably, 3 = just getting by, 4 = finding it difficult to make ends meet, 5 = not able to make ends meet).

Validation of questionnaires data at Level-2 interviews

The Level-2 BGR questionnaire was the same as that used for Level-1 and the answers were elaborated during the face-to-face interview.

To assess the participants’ lifetime psychiatric history we used the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (First et al, 2002). The interviews with subjects, except of straightforward controls, were reevaluated during team meetings by using audiotapes and notes of the interviews. The final diagnosis was confirmed by a senior consultant psychiatrist in every case.

As we published previously (Juhasz et al, 2009, Juhasz et al, 2011), based on these diagnoses, our BGR questionnaire has 91.7% sensitivity to identify lifetime major depression with 89.8% specificity (false positive cases: 3.4% for depression reported in the BGR but not meeting with SCID major depression criteria; false negative cases: 4.2% for absence of depression in the BGR but meeting SCID major depression criteria; 1.5% for hypomanic episodes, 0.7% for other psychiatric disorder).

Depressive symptom severity was rated by trained interviewers using the

Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (Montgomery and

Asberg, 1979) and also measured by self-reported BSI. There were highly significant (p < 0.001) correlations between the BSI symptom scores (scored in the same way as in Level-1) and the interview ratings (Pearson R = 0.77, n = 255; subjects who came for interview and also provided a Level-2 Questionnaire).

Interviewers were blind to the BSI data at the time of the interview. Supplemental References

Brugha T, Bebbington P, Tennant C, Hurry J (1985). The List of Threatening

Experiences: a subset of 12 life event categories with considerable long-term

contextual threat. Psychol Med 15:189-194.

Bartz JA, Hollander E (2006). Is obsessive-compulsive disorder an anxiety

disorder? Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 30:338-352.

Derogatis L (1993). BSI: Brief Symptom Inventory: Administration, Scoring, and

Procedures Manual. Minneapolis: National Computer Systems Pearson, Inc.

Derogatis, LR & Savitz, KL (2000). The SCL-90-R and the Brief Symptom

Inventory (BSI) in Primary Care In: Maruish ME (eds). Handbook of

psychological assessment in primary care settings, Volume 236 Mahwah,

NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp 297-334

Dohrenwend BS, Krasnoff L, Askenasy AR, Dohrenwend BP (1978).

Exemplification of a method for scaling life events: the Peri Life Events

Scale. J Health Soc Behav 19:205-229.

Fineberg NA, Saxena S, Zohar J, Craig KJ (2007). Obsessive-compulsive

disorder: boundary issues. CNS Spectr 12:359-375.

First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW (2002). Structured Clinical

Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version. Biometrics

Research (ed). Non-patient Edition (SCID-I/NP) ed. New York: New York

State Psychiatric Institute.

Hettema JM (2008). What is the genetic relationship between anxiety and

depression? Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 148C:140-146.

Hunt IM, Silman AJ, Benjamin S, McBeth J, Macfarlane GJ (1999). The

prevalence and associated features of chronic widespread pain in the community using the 'Manchester' definition of chronic widespread pain.

Rheumatology (Oxford) 38:275-279.

Juhasz G, Chase D, Pegg E, Downey D, Toth ZG, Stones K, et al. (2009). CNR1

Gene is Associated with High Neuroticism and Low Agreeableness and

Interacts with Recent Negative Life Events to Predict Current Depressive

Symptoms. Neuropsychopharmacology 34:2019-2027.

Juhasz G, Dunham JS, McKie S, Thomas E, Downey D, Chase D, Lloyd-Williams

K, et al (2011). The CREB1-BDNF-NTRK2 pathway in depression:

multiple gene-cognition-environment interactions. Biol Psychiatry.

69(8):762-71.

Lazary J, Lazary A, Gonda X, Benko A, Molnar E, Juhasz G, et al. (2008). New

evidence for the association of the serotonin transporter gene (SLC6A4)

haplotypes, threatening life events, and depressive phenotype. Biol

Psychiatry 64:498-504.

Montgomery SA, Asberg M (1979). A new depression scale designed to be

sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry 134:382-389.

Paykel ES, Prusoff BA, Uhlenhuth EH (1971). Scaling of life events. Arch Gen

Psychiatry 25:340-347.

Paykel ES, McGuiness B, Gomez J (1976). An Anglo-American comparison of

the scaling of life events. Br J Med Psychol 49:237-247.

Smith DJ, Nicholl BI, Cullen B, Martin D, Ul-Haq Z, Evans J, Gill JMR, et al.

(2013). Prevalence and Characteristics of Probable Major Depression and

Bipolar Disorder within UK Biobank: Cross-Sectional Study of 172,751

Participants PLoS One. 8(11): e75362.