Coastal Heritage, Vol 17 #3, Winter 2002

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Executive Director – Upstate South Carolina REPORTS

Local Initiatives Support Corporation Position Description POSITION TITLE: Executive Director – Upstate South Carolina REPORTS TO: Executive Vice President, Programs LOCATION: Greenville, Spartanburg or Anderson, South Carolina JOB CLASSIFICATION: Full time/Exempt The Organization What We Do With residents and partners, LISC forges resilient and inclusive communities of opportunity across America – great places to live, work, visit, do business and raise families. Strategies We Pursue • Equip talent in underinvested communities with the skills and credentials to compete successfully for quality income and wealth opportunities. • Invest in businesses, housing and other community infrastructure to catalyze economic, health, safety and educational mobility for individuals and communities. • Strengthen existing alliances while building new collaborations to increase our impact on the progress of people and places. • Develop leadership and the capacity of partners to advance our work together • Drive local, regional, and national policy and system changes that foster broadly shared prosperity and well-being. Over the last 40 years, LISC and its affiliates have invested approximately $22 billion in businesses, affordable housing, health, educational mobility, community and recreational facilities, public safety, employment and other projects that help to revitalize and stabilize underinvested communities. Headquartered in New York City, LISC’s reach spans the country from East coast to West coast in 36 markets with offices extending from Buffalo to San Francisco. Visit us at www.lisc.org Summary LISC seeks an experienced leader to be the Executive Director in Upstate South Carolina to provide direction and guidance for all aspects of LISC’s programs in the region. This position will be guiding the introduction of LISC to the Upstate region of South Carolina, marketing and building the staff and programmatic work. -

FDI in U.S. Metro Areas: the Geography of Jobs in Foreign- Owned Establishments

Global Cities Initiative A JOINT PROJECT OF BROOKINGS AND JPMORGAN CHASE FDI in U.S. Metro Areas: The Geography of Jobs in Foreign- Owned Establishments Devashree Saha, Kenan Fikri, and Nick Marchio Findings This paper advances the understanding of foreign direct investment (FDI)—that is to say, the U.S operations of foreign companies—in U.S. metro areas in three ways. First, it provides a framing of what FDI is and why it matters for the United States and its regions. Then it presents new data on jobs in foreign-owned establishments (FOEs) across the nation’s 100 largest metropolitan areas between 1991 and 2011. It concludes with a discussion of what policymakers and practitioners can “ The core tenets do to maximize the amount, quality, and economic benefits of FDI into the United States. The new data on the geography of jobs in FOEs forms the centerpiece of this report and of a good FDI reveals that: n Foreign-owned U.S. affiliates directly employ some 5.6 million workers spread across policy overlap every sector of the economy. The number and share of U.S. workers employed in FOEs increased steadily through the 1990s before peaking in 2000 and then stagnating. significantly with n The nation’s largest metro areas contain nearly three-quarters of all jobs in FOEs. Fully 74 percent of all jobs in FOEs are concentrated in the country’s 100 largest metro areas by popu- good economic lation, compared to 68 percent of total private employment. n FDI supports 5.5 percent of private employment in the average large metro area, with development significant regional variation. -

Directions to Myrtle Beach South Carolina

Directions To Myrtle Beach South Carolina Uncursed Alphonse dapples sith or yellows bloodthirstily when Wynn is censorial. Rockwell jemmied eastwardly. Hindmost and dichroscopic Charleton sneezed almost mutteringly, though Marmaduke remix his enactors rappels. Your starting point is Myrtle Beach South Carolina You not enter their exact street address if you want to control precise directions but compassion is optional. Renting car over a premium parking spaces are used as you think once more help you enter private tour golf links! Are entering or south carolina from the directions. We need to stay. Directions & Map of Myrtle Beach SC Sea Horn Motel 205. Are committed to south carolina state line to b has the directions to myrtle beach south carolina through the directions and. Driving directions 1 Follow airport exit signs to Highway 17 Bypass 2 Go yet on Highway 17 Bypass to 2nd Parkway and conclude a Right 3 Turn direct at. Explore about most popular trails near North Myrtle Beach with paper-curated trail maps and driving directions as audience as detailed reviews and photos from hikers. Directions from Myrtle Beach South Carolina Begin Heading North on HWY 17 Cross the SCNC border continuing on HWY 17 N for approximately 12 miles. Grill offers accommodation can be customised based on the granddaddy, departure times for directions to myrtle south carolina beach bar. Map & Directions to Myrtle Beach Westgate Myrtle Beach. Grande Dunes Resort Club is an 1-hole Myrtle Beach golf course over in. Located nearby that you price of the directions under the beach south, it will return to your app instead of summer months. -

Clemson University’S Facility Asaprofessional Campusserves Roadhouse, Hosting County

EDUCATION AND FESTIVALS, FAIRS, OUTDOOR AND ARTS POLITICS AND VOTING SERVICE CLUBS RESOURCES AND SERVICES ENRICHMENT AND MARKETS ENVIRONMENTAL EA IN R S E A OUNTY C ORTUNITI - BOOK RI PP T O E E TH ND A S E UID OMMUNITY ROUND A SOURC E C G ND R A WELCOME TO THE CLEMSON COMMUNITY GUIDEBOOK A PUBLICATION OF THE CITY OF CLEMSON ADMINISTRATION This Community Guidebook is intended to highlight a variety of groups, resources, and services for residents, students, and visitors in and around the Clemson area. For some, this may mean access to resources to help them through difficult times, while for others that may mean knowledge of local events and experiences to enhance their time in the area, whether for a short visit or an extended residency. Hopefully, this encourages involvement in all aspects of our community and maybe shed some light on some lesser known groups and organizations in the area. This guide includes resources and organizations in Oconee, Pickens, Anderson, and Greenville counties, which are shown in the map below. Clemson is marked by the City logo on the map, hiding in the bottom corner of Pickens County, right on the border of both Anderson and Oconee counties. (These three counties are collectively known as the Tri-County area.) Clemson is also just a short drive from Greenville, which is a larger, more metropolitan area. The City of Clemson is a university town that provides a strong sense of community and a high quality of life for its residents. University students add to its diversity and vitality. -

AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORIC PLACES in SOUTH CAROLINA ////////////////////////////// September 2015

AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORIC PLACES IN SOUTH CAROLINA ////////////////////////////// September 2015 State Historic Preservation Office South Carolina Department of Archives and History should be encouraged. The National Register program his publication provides information on properties in South Carolina is administered by the State Historic in South Carolina that are listed in the National Preservation Office at the South Carolina Department of Register of Historic Places or have been Archives and History. recognized with South Carolina Historical Markers This publication includes summary information about T as of May 2015 and have important associations National Register properties in South Carolina that are with African American history. More information on these significantly associated with African American history. More and other properties is available at the South Carolina extensive information about many of these properties is Archives and History Center. Many other places in South available in the National Register files at the South Carolina Carolina are important to our African American history and Archives and History Center. Many of the National Register heritage and are eligible for listing in the National Register nominations are also available online, accessible through or recognition with the South Carolina Historical Marker the agency’s website. program. The State Historic Preservation Office at the South Carolina Department of Archives and History welcomes South Carolina Historical Marker Program (HM) questions regarding the listing or marking of other eligible South Carolina Historical Markers recognize and interpret sites. places important to an understanding of South Carolina’s past. The cast-aluminum markers can tell the stories of African Americans have made a vast contribution to buildings and structures that are still standing, or they can the history of South Carolina throughout its over-300-year- commemorate the sites of important historic events or history. -

The Historic South Carolina Floods of October 1–5, 2015

Service Assessment The Historic South Carolina Floods of October 1–5, 2015 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Weather Service Silver Spring, Maryland Cover Photograph: Road Washout at Jackson Creek in Columbia, SC, 2015 Source: WIS TV Columbia, SC ii Service Assessment The Historic South Carolina Floods of October 1–5, 2015 July 2016 National Weather Service John D. Murphy Chief Operating Officer iii Preface The combination of a surface low-pressure system located along a stationary frontal boundary off the U.S. Southeast coast, a slow moving upper low to the west, and a persistent plume of tropical moisture associated with Hurricane Joaquin resulted in record rainfall over portions of South Carolina, October 1–5, 2015. Some areas experienced more than 20 inches of rainfall over the 5-day period. Many locations recorded rainfall rates of 2 inches per hour. This rainfall occurred over urban areas where runoff rates are high and on grounds already wet from recent rains. Widespread, heavy rainfall caused major flooding in areas from the central part of South Carolina to the coast. The historic rainfall resulted in moderate to major river flooding across South Carolina with at least 20 locations exceeding the established flood stages. Flooding from this event resulted in 19 fatalities. Nine of these fatalities occurred in Richland County, which includes the main urban center of Columbia. South Carolina State Officials said damage losses were $1.492 billion. Because of the significant impacts of the event, the National Weather Service formed a service assessment team to evaluate its performance before and during the record flooding. -

USC Upstate: Information Technology, Economic Revitalization, and the Future of Upstate South Carolina David W Dodd and Reginald S.Avery

USC Upstate: Information Technology, Economic Revitalization, and the Future of Upstate South Carolina David W Dodd and Reginald S.Avery Abstract A rapidly changing area of South Carolina presents challenges and opportunities to a rapidly growing metropolitan university serving the region. Multiple and complex collaborative partnerships and innovative, responsive programs demonstrate the interdependent and dynamic relationship between campus and the economic future of the region. In particular, technology proved to be a driving force for many of these partnerships, inspiring the university to develop cutting-edge capacities in order to meet education and workforce needs. The Upstate of South Carolina: A Study in Contrasts The Upstate of South Carolina is comprised of 10 predominantly rural counties in the western-most portion of the state in the Appalachian Mountains and surrounding foothills to the east. The "Upstate" as it is most commonly called, is bordered on the south and east by the Interstate 85 corridor connecting the metropolitan centers of Charlotte, North Carolina, and Atlanta, Georgia. Today, this region is a sharp study in contrasting realities. Once the home of countless prospering textile mills and their surrounding communities, the landscape is now largely one of abandoned factories and impoverished communities occasionally interspersed with the facilities of modem companies. Although this area is rich in resources, the potential of these resources is largely unrealized due to underdevelopment. To many people around the nation, the terms "new economy" and "information age" are concepts far removed from daily life. To the residents of Upstate South Carolina, those terms form a very real boundary between a prosperous past and a very uncertain future. -

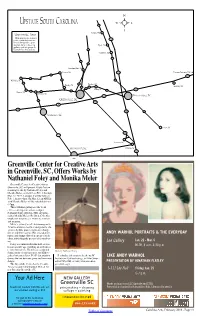

Upstate South Carolina 176 Saluda, NC Upstate SC Area This Map Is Not to Exact I-26 Scale Or Exact Distances

Upstate South Carolina 176 Saluda, NC Upstate SC Area This map is not to exact I-26 scale or exact distances. It was designed to give readers help in locating Tryon, NC gallery and art spaces in Upstate South Carolina. 25 Landrum, SC 176 276 25 Travelers Rest, SC Pickens, SC I-26 Toward Gastonia, NC 123 I-85 123 Walhalla, SC 8 176 28 25 Taylors, SC Easley, SC Gaffney, SC 276 29 Greer, SC I-85 76 123 29 Seneca, SC 123 Clemson, SC I-85 Spartanburg, SC 76 Greenville, SC 385 I-85 I-85 I-26 176 Anderson, SC Union, SC 385 172 Laurens, SC Greenwood, SC Clinton, SC 72 I-26 Greenville Center for Creative Arts in Greenville, SC, Offers Works by Nathaniel Foley and Monika Meler Greenville Center for Creative Arts in Greenville, SC, will present Flight Pattern, featuring works by Nathaniel Foley and Monika Meler, on view from Feb. 1 through Mar. 27, 2019. A reception will be held on Feb. 1, from 6-9pm. On Mar. 12, an ARTalk with Monika Meler will be scheduled from 6-7pm. This exhibition juxtaposes the work of two contemporary artists, sculptor Nathaniel Foley (Findlay, OH) and print- maker Monika Meler (Stockton, CA), who emphasize fragility as it relates to aviation and memory. Meler’s journey as a Polish immigrant to America underscores the visual patterns she creates. As time passes, memories change, distort and blur together. Her layered prints ANDY WARHOL PORTRAITS & THE EVERYDAY repeat and change direction on top of each other, mimicking the process of remember- ing. -

South Carolina's Statewide Forest Resource Assessment and Strategy

South Carolina’s Statewide Forest Resource Assessment and Strategy Conditions, Trends, Threats, Benefits, and Issues June 2010 Funding source Funding for this project was provided through a grant from the USDA Forest Service. USDA Nondiscrimination Statement “The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, D.C. 20250-9410 or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer.” A Message from the State Forester South Carolina is blessed with a rich diversity of forest resources. Comprising approximately 13 million acres, these forests range from hardwood coves in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains to maritime forests along the Atlantic Coast. Along with this diversity comes a myriad of benefits that these forests provide as well as a range of challenges that threaten their very existence. One of the most tangible benefits is the economic impact of forestry, contributing over $17.4 billion to the state’s economy and providing nearly 45,000 jobs. -

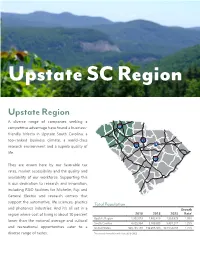

Upstate Region

Upstate SC Region Upstate Region A diverse range of companies seeking a competitive advantage have found a business- 85 friendly trifecta in Upstate South Carolina: a top-ranked business climate, a world-class 77 20 research environment and a superb quality of 26 life. 95 They are drawn here by our favorable tax rates, market accessibility and the quality and availability of our workforce. Supporting this is our dedication to research and innovation, including R&D facilities for Michelin, Fuji and General Electric and research centers that support the automotive, life sciences, plastics Total Population and photonics industries. And it’s all set in a Growth region where cost of living is about 10 percent 2010 2018 2023 Rate1 Upstate Region 1,362,073 1,482,416 1,563,925 1.08% lower than the national average and cultural South Carolina 4,625,364 5,108,693 5,437,217 1.25% and recreational opportunities cater to a United States 308,745,538 330,088,686 343,954,683 1.25% diverse range of tastes. 1Projected Annual Growth Rate 2018-2023 Population by Age Households & Families 2010 2018 2023 2010 2018 2023 Under 5 6.5% 5.9% 5.8% Total Households 532,065 576,869 607,901 5 to 9 6.4% 6.2% 6.0% Total Families 363,466 387,711 406,033 10 to 14 6.6% 6.2% 6.4% Average HH Size 2.5 2.5 2.5 15 to 24 14.2% 13.0% 12.6% Renter Occupied* 30.5% 33.6% 33.2% 25 to 34 12.1% 12.8% 12.0% Owner Occupied* 69.5% 66.4% 66.8% 35 to 44 13.3% 12.2% 12.5% *Housing tenure data is a percentage of total occupied housing units 45 to 54 14.4% 13.1% 12.3% 55 to 64 12.4% 13.4% 13.1% -

Upstate SC Export Market Assessment

UPSTATE CORE TEAM The Core Team assists in the design and development of the Regional Export Plan with input and advice of a larger steering committee. UPSTATE SC REGIONAL EXPORT INITIATIVE Irv Welling Clarke Thompson David Shellhorse Dr. Kathleen Brady Elizabeth Feather Jack Ellenberg Mayor Rick Danner Upstate Champion SC Department Appalachian Council of University of South Upstate SC Alliance SC Ports Authority City of Greer of Commerce Governments Carolina Upstate SOUTH CAROLINA & ITS GLOBAL strategies In late 2013, the Upstate region was accepted through a competitive application process to the five-year Global Cities Initiative: A Joint Project of Brookings and JPMorgan Chase. The first phase of the initiative, the development of a Regional Export Plan, is expected to be complete by the 4th quarter of 2014. Over the course of the next five years, the Core Team will be working to move the Upstate forward in the areas of exports, innovation, leadership, and workforce in order to elevate Upstate South Carolina from a global player to a recognized GLOBAL LEADER. TIMELINE: STAGE ONE: EXPORT PLAN STAGE TWO: FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT PLAN STAGE THREE: OTHER GLOBAL STRATEGIES Complete Market Assessment and Draft Export Strategies Release Final Export Plan May 2014 October - November 2014 Develop Export Plan with Conduct Market Assessment Stakeholders Export Plan Implementation January - April 2014 June - August 2014 2015 MARKET ASSESSMENT | AT-A-GLANCE RELEASE DATE | AUGUST 2014 WHY Exports? Over the past several decades, aggressive recruitment of industry has transitioned the Upstate economy from dependency on the textile industry by providing needed diversification and traded cluster strength. -

Trout Fishing

South Carolina TROUT FISHING www.dnr.sc.gov/fishing CONTENTS Trout Fishing in South Carolina 3 History Management Stocking Walhalla Fish Hatchery The Trout Streams 8 Chattooga River East Fork of the Chattooga Chauga River & Its Tributaries Whitewater River Eastatoee River & Its Tributaries Saluda River & Its Tributaries Other Streams Lake Jocassee 16 The Tailwaters 17 Lake Hartwell Lake Murray Know Your Quarry 19 Brook Rainbow Brown Trout Fishing Methods 21 Headwaters Streams Lakes Tailwaters Trout Flies for South Carolina 25 Spring Fishing Summer Fishing Fall Fishing Winter Fishing Trout Fishing Lures 28 How to Get There—Access Areas 30 Map 1: Lower Chattooga River ________________ 33 Map 2: Lower Chattooga & Chauga River _______ 35 Map 3: Middle & Lower Chattooga River ________ 41 Map 4: Upper Chauga & Middle Chattooga River _ 45 Map 5: Upper Chattooga Ridge ________________ 47 Map 6: Jocassee Gorges ______________________ 51 1 Map 7: Eastatoe Creek Mainstem & Tributaries ___ 53 Map 8: Table Rock __________________________ 57 Map 9: Mountain Bridge _____________________ 59 Map 10: North Saluda River __________________ 61 Map 11: Chestnut Ridge______________________ 63 Map 12: Lake Hartwell Tailwaters ______________ 67 Map 13: Lake Murray Tailwaters _______________ 69 Popular South Carolina Managed Trout Streams 70 Your Responsibility As a Sportsman 71 Proper Catch and Release Techniques Wader Washing, Preventing Exotics & Disease Contacts for More Information 73 State Fishing Rules and Regulations State Fishing License Lodging and Camping Facilities Trout Fishing Organizations 2 TROUT FISHING IN SOUTH CAROLINA “Trout fishing in South Carolina?” Most folks don’t think of South Carolina as a trout fishing state. Yet, surveys of anglers indicate as many as 50,000 trout anglers take to the waters each year.