Name ______1-3-2 The Basis of Cuneiform

The term "cuneiform" is very deceptive, in that it tricks people into thinking that it's some type of writing system. The truth is that cuneiform denotes not one but several kinds of writing systems, including logosyllabic, syllabic, and alphabetic scripts. In fact, "cuneiform" came from Latin cuneus, which means "wedge". Therefore, any script can be called cuneiform as long as individual signs are composed of wedges. Many languages, including Semitic, Indo- European, and isolates, are written in cuneiform.

Clay Tokens: The Precursors of Cuneiform

The earliest examples of Mesopotamian script date from approximately the end of the 4th millennium B.C.E., coinciding in time and in geography with the rise of urban centers such as Uruk, Nippur, Susa, and Ur. These early records are used almost exclusively for accounting and record keeping.

However, these cuneiform records are really descendents of another counting system that had been used for five thousand years before. Clay tokens have been used since as early as 8000 B.C.E. in Mesopotamia for some form of record-keeping.

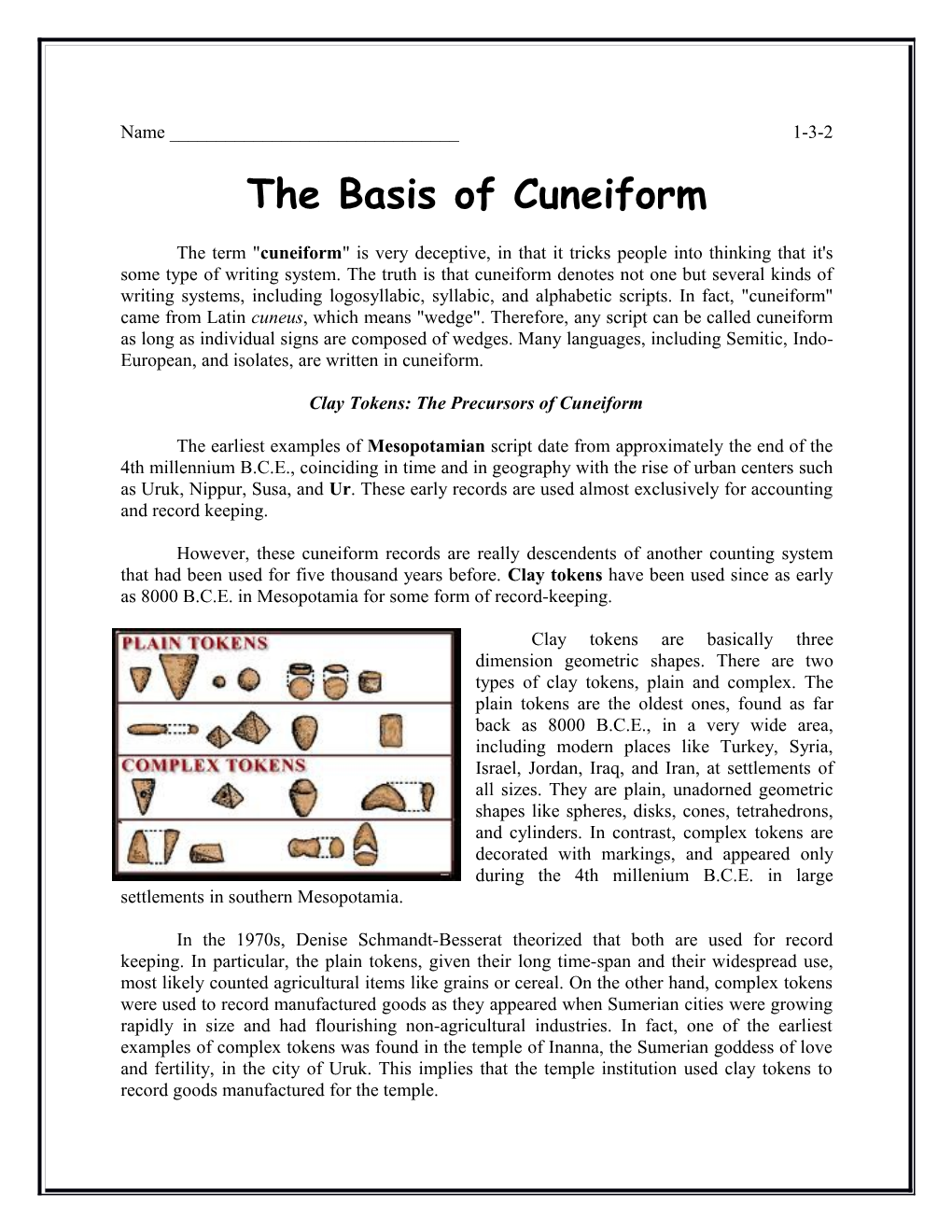

Clay tokens are basically three dimension geometric shapes. There are two types of clay tokens, plain and complex. The plain tokens are the oldest ones, found as far back as 8000 B.C.E., in a very wide area, including modern places like Turkey, Syria, Israel, Jordan, Iraq, and Iran, at settlements of all sizes. They are plain, unadorned geometric shapes like spheres, disks, cones, tetrahedrons, and cylinders. In contrast, complex tokens are decorated with markings, and appeared only during the 4th millenium B.C.E. in large settlements in southern Mesopotamia.

In the 1970s, Denise Schmandt-Besserat theorized that both are used for record keeping. In particular, the plain tokens, given their long time-span and their widespread use, most likely counted agricultural items like grains or cereal. On the other hand, complex tokens were used to record manufactured goods as they appeared when Sumerian cities were growing rapidly in size and had flourishing non-agricultural industries. In fact, one of the earliest examples of complex tokens was found in the temple of Inanna, the Sumerian goddess of love and fertility, in the city of Uruk. This implies that the temple institution used clay tokens to record goods manufactured for the temple. Often there would be more than one tokens, and in fact more than one type of token, in a single transaction. So how did the ancient Mesopotamians kept multiple tokens together without losing them? One answer was envelopes, where tokens are sealed inside a large clay hollow sphere. This was used primarily for plain tokens. Another solution, mostly used for complex tokens, was to string the tokens to a solid oblong piece of clay called a bulla which usually had seal impressions on it.

How do archaeologists know what these tokens actually represent? Well, many of the tokens, especially the complex ones, can be shown to evolve into cuneiform signs. For instance, the token with a disk space and cross markings evolved into the sign for sheep.

One key event that led to the transition of 3-D tokens to 2-D signs is that sealing plain tokens inside an envelop made it impossible to count how many tokens there are. The solution was to impressing the tokens onto the outside of the envelope (while the clay is still soft) before sealing them inside. So three impressions mean three tokens inside. Eventually, the process of putting tokens inside envelopes was abandoned and impression of tokens was used exclusively. Complex tokens got incorporated as well, but instead of making impressions of the tokens on the clay, the ancient Sumerian scribes used stylus to make wedge-like shapes into the clay to represent the token. However, instead of making the same sign three times to represent three items, the scribes used the sign for grain, which eventually became just a wedge, to denote quantity. A wedge came to represent "one", and a circle denotes "ten". So to write five sheep, the scribe impressed a wedge five times, and then made the sign for sheep. From this beginning the Sumerian writing system grew to become more than just an accounting device.