DRAFT

COMMON FINANCIAL STATEMENT FRAUD SCHEMES

Jamal Ahmad, JD., C.P.A. David Jansen, C.A. Jonny J. Frank, J.D., LL.M.

Contents

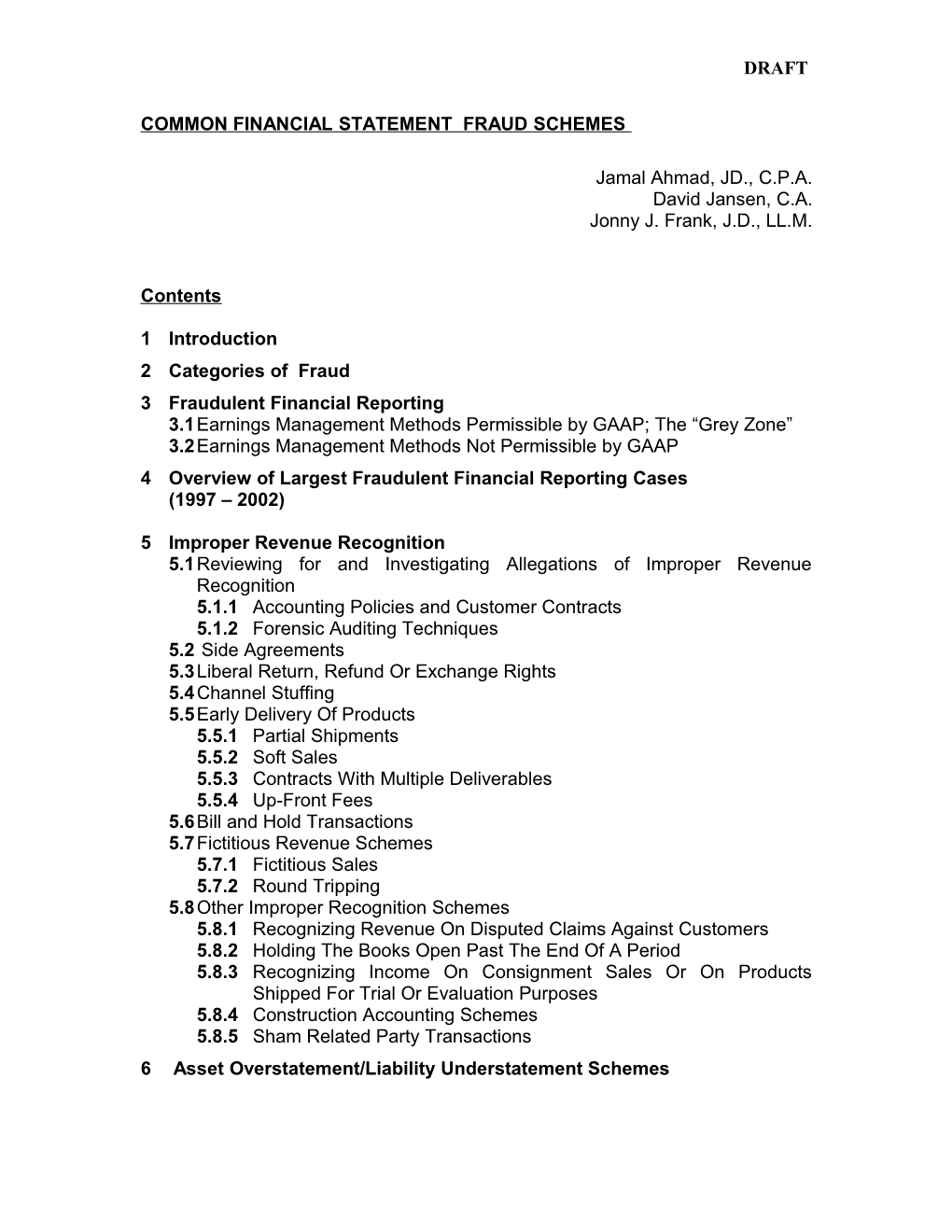

1 Introduction 2 Categories of Fraud 3 Fraudulent Financial Reporting 3.1Earnings Management Methods Permissible by GAAP; The “Grey Zone” 3.2Earnings Management Methods Not Permissible by GAAP 4 Overview of Largest Fraudulent Financial Reporting Cases (1997 – 2002)

5 Improper Revenue Recognition 5.1Reviewing for and Investigating Allegations of Improper Revenue Recognition 5.1.1 Accounting Policies and Customer Contracts 5.1.2 Forensic Auditing Techniques 5.2 Side Agreements 5.3Liberal Return, Refund Or Exchange Rights 5.4Channel Stuffing 5.5Early Delivery Of Products 5.5.1 Partial Shipments 5.5.2 Soft Sales 5.5.3 Contracts With Multiple Deliverables 5.5.4 Up-Front Fees 5.6Bill and Hold Transactions 5.7Fictitious Revenue Schemes 5.7.1 Fictitious Sales 5.7.2 Round Tripping 5.8Other Improper Recognition Schemes 5.8.1 Recognizing Revenue On Disputed Claims Against Customers 5.8.2 Holding The Books Open Past The End Of A Period 5.8.3 Recognizing Income On Consignment Sales Or On Products Shipped For Trial Or Evaluation Purposes 5.8.4 Construction Accounting Schemes 5.8.5 Sham Related Party Transactions 6 Asset Overstatement/Liability Understatement Schemes FIRST DRAFT

6.1Inventory Schemes 6.1.1 Inflating Inventory Quantity (Fictitious Inventory) 6.1.2 Inflating Inventory Value 6.1.3 Fraudulent Or Improper Inventory Capitalization 6.2 Accounts Receivable Schemes 6.2.1 Creating Fictitious Receivables 6.2.2 Artificially Inflating The Value Of Receivables 6.3 Investment Schemes 6.3.1 Fictitious Investments 6.3.2 Manipulating The Value Of Investments Misclassification of Investments Recording Unrealized Declines in Fair Market Value/Overvaluation 6.4 Improper Capitalization of Expenses 6.4.1 Software Development 6.4.2 Research and Development 6.4.3 Start Up Costs 6.4.4 Interest Costs 6.4.5 Advertising Costs 6.5 Recording Fictitious Fixed Assets 6.6g Depreciation and Amortization Schemes 7 Understatement of Liabilities 7.1General 7.2Off Balance Sheet Entity Schemes 7.2.1 Off Balance Sheet Treatment versus Consolidation 7.2.2 The Old Rules 7.2.3 The “New” Rules 7.3Overstatement of Liability Reserves (“Cookie Jar Reserves”)

8. Improper or Inadequate Disclosures 9. Materiality 10 Misappropriation of Assets 10.1 Misappropriation of Cash 10.1.1 Skimming of Cash Unrecorded or Understated Sales or Receivables Lapping 10.1.2Fraudulent Disbursements Billing Schemes - Creation of Fictitious Vendors or Shell Companies to Convert Monies Billing Schemes - False Credits, Rebates, Refunds and Kickbacks Billing Schemes - Over billing Billing Schemes - Pay and Return Schemes Theft of Company Checks Payroll Fraud - Ghost Employees

2 FIRST DRAFT

Payroll Fraud - Falsified Hours 10.2 Misappropriation of Inventory Conversion of Inventory 10.2.1Conversion of Inventory 10.2.2False Write-Off’s and Other Debits to Inventory 10.2.3False Sales of Inventory

11. Other Fraudulent Revenue and Expenditures 11.1 Revenue And Assets Obtained By Fraud 11.2 Expenditures and Liabilities For An Improper Purpose

3 FIRST DRAFT

1. Introduction

Statement on Auditing Standards No. 991 (“SAS 99”) requires auditors to focus on two broad areas of fraud: (i) fraudulent financial reporting and (ii) misappropriation of assets. Each of these has a multitude of fraud schemes. This chapter provides an overview of the most common financial statement fraud schemes, indicators of their occurrence, and methods of detection.

The focus is to familiarize the reader with certain fraud schemes, the various indicators which evidence that these schemes may be or are being perpetrated and how an auditor might detect those schemes. While this chapter discusses numerous fraud schemes, it does not contain a comprehensive list of all possible schemes. Similarly, with respect to the listed schemes, space constraints prevent discussion of all possible detection procedures the auditor can perform to determine whether the particular scheme exists.

2. Categories of Fraud

Fraud schemes can be grouped in various categories. For example, from a legal perspective, frauds can be distinguished between: frauds by the corporation and frauds against the corporation. Frauds committed by the corporation carry legal risk, that is, potential civil, regulatory, and criminal liability. Frauds committed against the corporation carry financial risk, that is, the loss of income or assets. External and internal misappropriations of assets are by far the most common fraud against the corporation.

This chapter groups, financial frauds into four broad categories: Fraudulent Financial Reporting Schemes; Misappropriation Of Assets; Revenue And Assets Obtained By Fraud and Expenditures and Liabilities For An Improper Purpose

4 FIRST DRAFT

Most auditors would consider only to the first two categories (fraudulent financial reporting and misappropriation of assets) to be financial statement frauds. The final two categories although financial in nature, are not generally considered to be financial statement frauds, as they do not impact upon the balances in the financial statements.

3. Fraudulent Financial Reporting

Most fraudulent financial reporting schemes involve “earnings management”, which the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) has defined as “the use of various forms of gimmickry to distort a company’s true financial performance in order to achieve a desired result.”2

Earnings management, however, does not always involve outright violations of Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (“GAAP”) - - more often than not, entities manage earnings by choosing accounting policies that bend GAAP to attain earnings targets. Thus, it is important to distinguish between earnings management techniques that are aggressive in nature but otherwise permitted by GAAP, and those that clearly violate GAAP.

Accountants working with public companies, however, take note. The SEC takes the position that compliance with GAAP will not necessarily protect an entity from an SEC enforcement action, if financial performance is distorted.3

3.1 Earnings Management Techniques Permissible Under GAAP: The “Grey Zone”

GAAP frequently allows management alternative ways to record the operations of an entity. For instance, GAAP allows any depreciation method, so long as it systemically and rationally allocates the cost of the asset over its useful life. 4 Similar instances in which management is provided wide latitude include:

5 FIRST DRAFT

Changing depreciation methods from an accelerated method to the more conservative straight-line method or vice versa; Changing the useful lives or the estimates of salvage values of assets; Determining the appropriate allowance required for uncollectible accounts receivable; Determining whether/when assets have become impaired and are required to be reserved against or written off; Choosing an appropriate method of inventory valuation (LIFO, FIFO, specific identification etc.); Determining whether a decline in the market value of an investment is temporary or permanent; and Estimating the write-downs required for investments.

Thus, in certain instances, GAAP “allows” a company to manage earnings by simply altering its accounting policy to select those accounting principles that benefit it most. The SEC itself has noted that accounting principles are not meant to be a straightjacket and that flexibility of accounting is essential to innovation.5 Abuses occur, however, when this flexibility is exploited to distort the true picture of the corporation.6

Entities have a host of reasons for selecting those principles that will paint the rosiest financial picture. Some would argue that the market demands it, as reflected by the stock price punishment for companies that differ by as little as one penny per share from prior estimates. External market pressures to “meet the numbers” conflicts with market pressure for transparency in financial reporting.

Often, it is difficult to distinguish between “aggressive”, but allowable accounting and that which is abusive and prohibited. How, for example, does one determine whether management’s reserve for uncollectible accounts is or is not reasonable?

The line between aggressive and fraudulent behavior hinges on management ‘s intent. Fraud rarely occurs if management’s intent is transparent and clearly

6 FIRST DRAFT understandable. What, however, if management selects a GAAP permissive policy to conceal a fraud or error? Does the selection of the otherwise allowed policy demonstrate intent to commit fraud? Consider also whether management selects a policy that it knows will have both a positive and negative effect on the financial picture. If management selects the policy but refuses to recognize the negative effect, does that demonstrate fraud in the selection of the policy?

Whether a fraud has been committed is fact-specific. For purposes of this chapter, we have assumed that management has acted with malicious intent. The case examples cited also involve instances where the company and/or its management was charged and most often found guilty of wilfully engaging in the alleged misconduct.

3.2 Earnings Management Methods Not Permissible by GAAP

Some financial frauds have no grey; that is, earnings management that are clearly not within the parameters of GAAP. These techniques can inflate earnings, create an improved financial picture, or conversely, mask a deteriorating one.

Examples cited by the SEC include: “Big Bath” charges; Creative acquisition accounting; “Cookie jar” liability reserves; Use of materiality to record small but intentional misstatements in the financial statements; and Revenue recognition irregularities.7

4. Overview of Largest Fraudulent Financial Reporting Fraud Cases (1997 – 2002)

To demonstrate the breadth of recent fraud cases, the table below outlines some of the larger and more publicized frauds and accounting scandals detected over the period 1997 – 2002. The schemes involved an array of industries and

7 FIRST DRAFT

included both frauds “by” and “against” the entity as well as corporate misconduct.

Company Fraud Scheme Result Adelphia Misappropriation of firm assets Declared bankruptcy in Communications by executives for personal use. January 2002. CEO and Concealment of $2.3 billion in family members charged with loans to cover losses by founder fraud. and family members. Cendant Corp. As a result of its merger of HFC Restated 1997 earnings with CUC International, it was decreased by more than $161 revealed that CUC overstated million. revenue by $500 million between Former CFO, VP, and 1995 and 1997 using assorted controller pled guilty to techniques such as recording numerous other charges. fictitious revenues and Company settled $3.2 billion understating liabilities. shareholder suit Ernst & Young paid $335 million to settle shareholder lawsuit. Enron Overstated income by Declared bankruptcy in intentionally understating December 2001. liabilities and concealing debt Lost more than $80 billion in through the creation of off market capitalization. balance sheet entities. Former CFO among others Inadequately disclosed Co.’s off convicted of money balance sheet transactions. laundering and securities, Possible tax evasion. wire and mail fraud. Additional charges brought against others. Resulted in dissolution of company and accountants Arthur Anderson. Global Crossing Charged with using "swap deals" Declared bankruptcy January with other telecom carriers to 2002. inflate sales. SEC investigations pending. K-Mart Inflated revenue by improperly Declared bankruptcy, January recognizing entire $42.3 million in 2002. revenue from a multiyear Two former VPs charged with contract in 2nd quarter of 2001. earnings fraud. MicroStrategy Improperly recognized revenue Restated earnings for fiscal from sales of software as years 1998 and 1999, which agreements were entered into caused revenues to be rather than as services were reduced by almost $66 provided. million.

8 FIRST DRAFT

Company Fraud Scheme Result Former CEO, COO, and CFO each fined $350,000. Sunbeam Corp. Created $35 million in Restated 1997 income from inappropriate restructuring $109 million to $38 million. reserves in 1996 that were CEO charged with violating reversed in 1997 to inflate federal securities laws by income thus creating the illusion misrepresenting material of a rapid turn around. information about the In 1997, reported over $70 company. CEO settled by million of revenue from bill and paying a piece of a $141 hold sales, channel stuffing and million fine. other inappropriate accounting Former controller and chief practices. accounting officer each agreed to pay $100,000 in fines. Former Arthur Anderson partner also settled for undisclosed amount. Tyco Misappropriation of $600 million Three former executives International by CEO and CFO for personal including CEO and general use through theft and the false counsel arrested for fraud. sale of securities. CEO also charged with Company also separately sued avoiding payment of over $1 former CEO seeking the return of million in sales taxes on $13 more than $100 million. Suit million of artwork alleges CEO gave himself unauthorized bonuses totalling $58 million and unauthorized loans of more than $43 million, and of taking personal credit for more than $43 million in charitable donations that actually were made by Tyco. WorldCom Intentionally improperly Declared bankruptcy, July capitalized billions of dollars of 2002. Former finance chief expenses as capital and finance and accounting expenditures. executives charged with Former CEO facing possible securities fraud. charges for allegedly profiting improperly from IPOs offered by brokerages in return for investment banking business. Xerox Overstated revenue for over 4 Co. agreed to pay $10 million years by accelerating the in fines and restate its income recognition of $3 billion in for the years 1997-2000.

9 FIRST DRAFT

Company Fraud Scheme Result revenue and inflating earnings by about $1.5 billion. Alleged SEC sued three current scheme included the recognition KPMG partners and one of revenue on its office copier former partner of securities leases too early in their cycles. fraud in the claiming the firm fraudulently let the Co. manipulate its accounting practices to fill a $3 billion gap and make it appear to be meeting market expectations.

5. Improper Revenue Recognition

Improper recognition of revenue - either prematurely or of fictitious revenue – is the most common form of fraudulent earnings management. Premature recognition of revenue involves the recording of revenue generated through legitimate means, at any time prior than would be allowed under GAAP. Premature recognition should be distinguished from recognition of fictitious revenue derived from false sales or to false customers.

The Report of the National Commission on Fraudulent Financial Reporting (hereinafter, “ the COSO Report”)8 found that improper revenue recognition was alleged in 47% of the cases reviewed by the Commission from 1981 to 1986. A second COSO Report found that the number of revenue recognition alleged matters accounted for 50% of all matters enforced by the SEC from 1987-1997.9

According to SEC figures, 32 of the 90 actions bought by the Commission in 1999 involved improper revenue recognition using such techniques as side letters, rights of return, consignment sales, and the shipping of unfinished products. Another 12 cases involved the booking of fictitious sales.10

A PricewaterhouseCoopers study revealed that in the year 2000, 66% of the shareholder actions filed alleged revenue recognition violations.11 In 2001, the number of revenue recognition actions jumped to 69% of all actions filed.12

10 FIRST DRAFT

Finally, of the approximately 140 earnings management/accounting cases brought by the SEC in 2002, more than half related to revenue recognition.13

With respect to premature recognition, SEC Staff Accounting Bulleting 101, Revenue Recognition in Financial Statements, (“SAB 101”) 14 spells out four basic criteria that must be met before a public company may recognize revenue. Specifically, these criteria require:

Persuasive evidence that an arrangement exists; Evidence that delivery has occurred or that services have been rendered; A showing that the seller's price to the buyer is fixed or determinable; and Ability to collect payment must be reasonably assured.

SAB 101 echoes the recognition requirements originally listed in AICPA Statement of Position (“SOP”) 97-2, Software Revenue Recognition15, which governs the software industry. Accountants should also refer to industry specific literature depending upon the client and circumstances.16 In fact, SAB 101 explains that where it exists, companies should apply industry specific authority over SAB 101.

Many of the schemes described in this chapter violate more than one of the SAB 101 recognition criteria. The indicia for each listed scheme are not mutually exclusive; that is; factors indicating the potential existence of one scheme can often be used to detect others.

Companies can use numerous methods to engage in premature or fictitious revenue recognition. Following are the most common techniques:

Agreements or policies which grant liberal return, refund or exchange rights; Side agreements; Channel stuffing; Early delivery of product . Contracts with multiple deliverables; . Soft sales; . Partial shipments; and . Up-front fees; Bill and hold transactions;

11 FIRST DRAFT

Recording false sales to existing customers and false sales to fictitious customers; Round tripping Other forms of improper recognition: . Recognizing revenue on disputed claims against customers; . Holding the books open past the end of a period; . Recognizing income on consignment sales or on products shipped for trial or evaluation purposes; and . Improper accounting for construction contracts ; and Sham related party transactions.

5.1 Reviewing For and Investigating Allegations of Improper Revenue Recognition

5.1.1 Accounting Polices and Customer Contracts

Inquiries into alleged improper revenue recognition usually begin with a review of the entity’s revenue recognition policies and customer contracts. The auditor considers the reasonableness of the company’s normal recognition practice and whether the company has done everything necessary to comply. For example, if the company customarily obtains a written sale agreement, the absence of a written agreement becomes a red flag.

The review should begin with a detailed reading of the contract terms and provisions. Particular attention should be focused upon terms governing (i) payment and shipment, (ii) delivery and acceptance, (iii) risk of loss, (iv) terms requiring future performance on the part of the seller before payment, (v) payment of up-front fees, and (vi) other contingencies. The auditor must consider timing – particularly as it relates to the company’s quarter and year-end periods. In which periods were the sales agreements obtained? When was the product or equipment delivered to the buyer’s site? When did the buyer become obligated to pay? What additional service(s) was required of the seller?

In the absence of a written agreement, the auditor should consider other evidence of the transaction, e.g. purchase orders, shipping documents, payment records, etc. He or she should also consider SAB 101 as well pronouncements

12 FIRST DRAFT specific to the particular business, as accounting literature often contains relevant examples and issues. For example, companies engaged in business over the internet face unique revenue recognition issues. The Emerging Issues Task Force Abstract (“EITF”) 99-19, Reporting Revenue Gross as a Principal versus Net as an Agent, 17 attempts to solve this problem by listing factors which are considered by the SEC in determining whether revenue should be reported on a gross or net basis. Similarly EITF 01-9, Accounting for Consideration Given by a Vendor to a Customer (Including a Reseller of the Vendor’s Products),18 addresses the issue of sales incentives, such as discounts, coupons, rebates, and "free" products or services offered by manufacturers to customers of retailers or other distributors. Being aware of the applicable authority governing the facts and circumstances can assist the auditor in his determination of recognition violations.

5.1.2 Forensic Auditing Techniques

The auditor should perform the following techniques when investigating revenue recognition allegations: Inquire of management and other relevant personnel as to the existence factors causing the auditor to believe the scheme exists19; Perform substantive analytics designed to detect the fraud being investigated; and Perform substantive testing to determine whether there is evidence to support the existence of a scheme or lack of evidence to support the validity of a transaction. Such substantive procedures include but are not limited to: - Request and review documents such as contracts and support for invoices and deliveries; - Confirmation with customers to the existence of accounts receivable and the amount of consigned goods; - Possible public records/background research/site visits conducted on customers/third parties to verify existence of the entity being billed; - Analyzing journal entry activity and supporting documentation in certain accounts, focusing on round dollar entries at the end of periods;

13 FIRST DRAFT

- If entries are accruals, obtaining support for the reversal and confirming the proper timing of the entries.

The following general indicators can often alert the auditor or auditor as to the potential existence of premature revenue recognition: Unexplained change in recognition policies; Unexplained improvements in gross margin; Increasing sales with no corresponding increase in cash from operations; Reported sales, revenue or accounts receivable balances which appear to be to high or are increasing too fast; Reported sales discount, sales returns or bad debts expenses which appear to be too low; Large, numerous or unusual sales transactions occurring shortly before the end of the period; Large amounts of returns or credits after the close of a period; or Inconsistent business activity – - Increased revenues with no corresponding increase in distribution costs or - Increased revenues with no offsetting increase in accounts receivable.

The use of analytics should also not be overlooked as a means of detecting fraud. Analytical procedures and relationships the auditor can perform or review to determine whether revenue is being recognized prematurely include: Comparing current period financial statement line item amounts with amounts from prior periods and inquiring as to significant changes in accounts between periods (Horizontal Testing, See Chapter ); Reviewing balances in revenue related accounts for unusual changes; Calculating the percent of sales and receivables to the total balance sheet in the current period, comparing it with prior periods and inquiring of any unusual changes (Vertical Testing, See Chapter ) ; Reviewing the statement of cash flows to determine if cash collected is in proportion to reported revenues; Reviewing sales activity for the period and note any unusual trends or increases such as increases towards the end of the period; Significant or unusual or unexplained changes in the following particular ratios (See Chapter XX for a detailed explanation of ratios): o Increases in Net Profit Margin (Net Income/Total Sales); o Increases in Gross Profit Margin (Gross Profit/Net Sales); o Increases in the Current Ratio (Current Assets/Current Liabilities); o Increases in the Quick ratio (Cash and Receivables and Marketable Securities/Current Liabilities);

14 FIRST DRAFT

o Increases in the Accounts Receivable Turnover (Net Sales/A/R); o Increases to Days Sales Outstanding (A/R Turnover/365); o Increases in Sales Return Percentages (Sales Returns/Total Sales); o Increase in Asset Turnover (Total Sales/Average Total Assets); o Increases in Working Capital Turnover (Sales/Average Working Capital); o Decrease in A/R Allowance as a % of A/R (Allowance/Total A/R); and o Decreases in the bad debt expense or allowance accounts.

Of course, good interviewing and sound analytics will not substitute for having a good understanding of the client’s business. Even seasoned auditors have been misled and thought revenue to be appropriate because they did not fully understand the business. Thus, after all the analytics and interviews, the auditor must ask him or herself whether the information and results obtained make sense in light of the client’s industry and business. The auditor should also to the extent applicable, benchmark performance results against other companies in the same industry.

5.2 Side Agreements

While SAB 101 requires a definitive sales or service agreement, agreements can and often are legitimately amended. Problems arise however when a company enters into such an arrangement and subsequently modifies, supplements, revokes, or otherwise amends the original agreement with a written or oral side agreement prepared and agreed to outside the normal reporting channels of the business.

Management often employ side arrangements or letters to boost sales figures. Sales force members also use them to meet sales targets or to obtain undeserved commissions. Side agreements created outside of the normal and proper recording channels are often used to perpetrate many of the schemes listed in this chapter.

15 FIRST DRAFT

The existence of numerous side agreements should raise red flags to the auditor and require further detailed inquiry as to the facts and circumstances surrounding how, when and why the agreements were entered into. Additional investigation is warranted if the inquiry points to preparation outside the normal reporting channels.

Common side agreement fraud schemes involve: Liberal or unconditional rights of return granted to customers; Rights to cancel orders at any time; Contingencies that nullify the sale, such as: o Re-sale; o Receipt of funding; Rights of continuing negotiations; and Extension of payment terms.

Case Illustration The case of Informix Corp illustrates the improper use of side-agreements. 20 Informix sold licensed software to companies, which, in turn, would resell the licenses to third parties. Consistent with then current GAAP for revenue recognition with respect to software21, the company’s written policy was to recognize revenue from the sale of licenses only upon receipt of a signed and dated license agreement. However, to meet the earnings expectations of the company and financial analysts, management entered into numerous written and oral side agreements containing different provisions, which caused them to violate GAAP revenue recognition principles. These provisions included: Allowing resellers to return and to receive a refund or credit for unsold licenses; Committing the company to use its own sales force to find customers for resellers; Offering to assign future end-user orders to resellers; Extending payment dates beyond twelve months; Committing the company to purchase computer hardware or services from customers under terms that effectively refunded all, or a substantial portion, of the license fees paid by the customer; Offering to pay for customer storage costs; Diverting the company's own future service revenues to customers as a means of refunding their license fees; and

16 FIRST DRAFT

Paying fictitious consulting or other fees to customers to be repaid to the company as license fees.

Auditors should perform inquiries of management, accounting and sales personnel as to whether they are made aware of all side agreements entered into by the other party that modify sales in any one of the methods mentioned or in any other fashion. The auditor should also inquire of sales people whether they are allowed or encouraged to use side letters or agreements to complete a sale and whether these agreements are made using proper reporting channels.

In addition to inquires, the auditor should review the company’s right of return policy and understand its rationale. The auditor should satisfy him or herself by reviewing a sample of contracts for side agreements and confirm with a sample of customers the major contract terms of their contracts, including the existence or absence of any side agreements.

5.3 Liberal Return, Refund, Or Exchange Rights

Most industries allow customers to return products to sellers for any number of reasons, and GAAP allows entities to recognize revenue in certain cases even though the customer may have a right of return. Specifically, Statement of Financial Accounting Standard (“SFAS”) No. 48, Revenue Recognition Where Right of Return Exists22 provides that when customers are given a right of return, revenue may be recognized at the time of sale if the: Sales price is substantially fixed or determinable at the date of sale; Buyer has paid or is obligated to pay the seller; Obligation to pay is not contingent on resale of the product; Buyer's obligation to the seller does not change in the event of theft or physical destruction or damage of the product; Buyer acquiring the product for resale is economically separate from the seller; Seller does not have significant obligations for future performance or to bring about resale of the product by the buyer; and Amount of future returns can be reasonably estimated.23

17 FIRST DRAFT

Sales revenue not recognizable at the time of sale is recognized either when the return privilege has substantially expired or if the above conditions are subsequently met. Companies can and often do run astray of SFAS 48 by establishing accounting policies or creating sales agreements which (i) grant customers vague or liberal rights of returns, refunds or exchanges, (ii) fail to fix the sales price, (iii) make payment contingent upon resale of the product or some other future event such as the receipt of funding from a lender.

Payment terms that extend over a substantial portion of the period in which the customer is expected to use or market the purchased products also create problems. These terms effectively create consignment arrangements inasmuch as no economic risk has been transferred to the purchaser. As will be discussed in Section 5.9.3, sales under consignment arrangements cannot be recorded as revenue.

Case Illustration In the case of Midisoft Corporation, 24 the SEC charged the company with overstating revenue on in the amount of $458,000 on transactions for which products were shipped, but for which, at the time of shipment, the company had no reasonable expectation that the customer would accept and pay for the products. The company eventually accepted back most of the product as sales returns during the first quarter of the subsequent period.

The SEC noted that Midisoft’s written distribution agreements generally allowed the distributor wide latitude to return product to Midisoft for credit whenever the product was, in the distributor's opinion, damaged, obsolete, or otherwise unable to be sold. In preparing Midisoft's financial statements for fiscal 1994, company personnel submitted a proposed allowance for future product returns that was unreasonably low in light of the large levels of returns Midisoft received in the first several months of 1995. Furthermore, various officers and employees in the company’s Accounting and Sales Departments knew the exact amount of returns

18 FIRST DRAFT the company had received prior to the end of March 1995, when the company’s independent auditors finished their field work on the 1994 audit. Had Midisoft revised the allowance for sales returns to reflect the returns information, it would have had to reduce accordingly the amount of net revenue reported for fiscal 1994. Instead, several Midisoft officers and employees devised schemes to prevent the auditors from discovering the true amount of the returns including preventing the auditors from touring that portion of the Midisoft headquarters where the returned goods were stored. In addition, Midisoft accounting personnel altered records contained in the computer accounting system to reduce falsely the level of returns.

Midisoft teaches that the auditor should carefully review the terms of the contracts and any side or extension agreements to determine what rights are afforded the customer with respect to returning and exchanging the delivered product. Only in those cases where the customer has limited or no right to return the product should revenue be recognized. The auditor should also inquire into the company’s refund and exchange policy: how it was derived, whether it is subject to override, by whom and how often it is overridden. Other relevant inquiries include sales personnel as to whether the company has offered customers price concessions, refunds, or new products.

Auditors should also inquire of accounting staff and financial personnel as to the returns policy and confirm with warehouse personnel who process returns that the policy is being followed. In addition to the inquiries, the auditor may also choose to perform the following analytics:

Compare returns in current period to prior periods and inquire as to any unusual increases; Determine whether returns are processed timely (this may require a visit an inquiry with warehouse personnel, an inquiry can also be made of customers on confirmations) o Companies may slow down the return processing process to avoid reducing sales in the current period.

19 FIRST DRAFT

Perform sales return percentage (Sales Returns/Total Sales) and inquire as to any unusual increase; and Compare returns subsequent to reporting period to both the return reserve and the monthly returns for reasonableness.

5.4 Channel Stuffing

Channel stuffing refers to the practice of offering deep discounts, extended payment terms or other concessions to customers to induce the sale of products in the current period, when they would not have not been otherwise sold until later periods, if at all.

Case Illustration The case against Sunbeam Corporation25 is illustrative. In December 1997, Sunbeam established a program offering discounts, favourable payment terms, guaranteed mark-ups and the right of return or exchange on unsold products to any distributor willing to accept the company’s products before year-end. The company failed to disclose this practice in its quarterly 10Q. As a result, the SEC charged that the company’s 10Q statement was misleading and that the company had eroded future sales and profit margins by pulling them into the current period.

Channel stuffing often is indicated by an increase in shipments, which is usually accompanied by an increase in shipping costs, at or near the end of period. Where these circumstances occur, the auditor or auditor should (i) inquire whether the goods were sold at steep discounts and (ii) review customer contracts and side agreements for unusual discounts in exchange for sales and rights of return provisions. The auditor should also inquire of sales personnel and shipping personnel regarding management influence to alter normal sales channel requirements.

20 FIRST DRAFT

In addition, customers offered deep discounts often purchase inventory in excess of required needs to take advantage of the reduced prices. This excess, inventory is often returned by the customer after the close of the period as it cannot be resold. The auditor thus should consider the amount of returns shortly after the close of a period as compared to prior periods and margins on sales recorded immediately before the end of a reporting period.

5.5 Early Delivery of Product

Companies can circumvent the SAB 101 delivery requirement in a variety of ways including: Shipping unfinished or incomplete products to customers, or at a time prior to when customers are ready to accept them; Engaging in “soft sales” (shipping of products to customers who have not agreed to purchase); Recognizing the full amount of revenue on contracts where services are still due to the client, and/or Recognizing the full amount of revenue on fees collected up front.

Based on the provisions of SAB 101, income should not be recognized under these circumstances because delivery has not actually occurred.

Customers on the other side of early delivery schemes often return the unfinished product or demand more completion before payment is rendered. Analytics that may reveal the existence of an early delivery scheme include: Comparing returns in the current period and prior periods; Comparing shipping costs in current period and prior periods; and Comparing shipping costs as a percentage of revenue in the current period and prior periods.

Careful scrutiny of the sales contract will also assist to detect these schemes. When must payment be made in relation to delivery? Which party bears the risk of loss on shipment? The audit or investigative team should then compare these contract terms with the requirements of SAB 101 and other accounting literature.

21 FIRST DRAFT

The auditor should also make broad inquiries of non-financial personnel such as:

Shipping department personnel: Were shipments earlier than normal for customers? Is inventory stored in the warehouse documented as shipped? Was there inventory shipped to addresses other than customer sites? Were there any adjustments to shipping dates? Whether there exists consigned goods and their location. Sales force personnel: Are shipments of any products designed to arrive ahead of the customer’s required delivery date? Do sales personnel pick up product and deliver to customers? Are there sales personnel with excessive “samples”? Do sales personnel have free reign in access to the warehouse? Warehouse personnel: - Are there any misstatements in the amount of merchandise the company ships or receives? - Has there been destruction, concealment, predating, or postdating of shipping and/or inventory documents? - Has there been an acceleration of shipments prior to month or year- end? - Have there been shipments to a temporary or holding warehouses prior to final shipment to the customers’ premises? - Are there any other unusual, questionable, or improper practices?

Additional audit procedures include: Comparing the purchase order date with the shipment date; Determine whether sales personnel are paid commissions based on the sale of product or upon collection; Inquiring of outside related business interests of key/sales personnel that may be suspected in an improper revenue recognition scheme; Performing public records searches on certain entities and individuals; Determining whether shipments have been made to these outside business interests; Reviewing amounts and trends of shipping costs at or near the end of a period even to legitimate customers; Reviewing rate of returns; Inspecting shipping documents for missing, altered or incorrect information; and Reviewing customer complaint logs or e-mail correspondence for complaints of shipments of goods prior to the customer’s readiness to accept.

22 FIRST DRAFT

5.5.1 Partial Shipments

Many companies will prematurely recognize 100% of revenue on partial or incomplete shipments of customer orders. The delivery requirement is not met, if the unshipped portion constitutes a substantial portion of the total deliverable.

Case Illustration The SEC’s enforcement action against FastComm Communications Corp is illustrative.26 In 1999, the SEC charged FastComm with recognizing revenue on the sale of products that were not fully assembled or functional. The SEC charged that it was improper because delivery had not yet occurred.

Auditing for partial shipments is similar to auditing for early product delivery. The auditor must consider: Numerous returns of incomplete products after the close of period by customers seeking the full product; Large, numerous or unusual transactions occurring shortly before the end of the period; Examining product details on the invoices; Is the invoice cut with all products ordered whether shipped or not? . Obtain understanding of drop shipments to customers; if a drop shipment is partial, is the invoice to the customer also partial? . How does the company ensure all drop shipped products are properly accounted for in the sales invoice process and also in paying for the goods to the supplier? Reviewing customer complaints regarding lack of completeness in shipments.

In addition, the auditor will want to inquire of management and sales personnel regarding the policy and process for billing partially filled orders. A review of the shipping documents and comparison to the sales journal will also often reveal what was booked as sales and what was actually shipped. The auditor may also consider talking to customers or reviewing correspondence from customers to see if there are numerous complaints from customers regarding partial shipments.

23 FIRST DRAFT

5.5.2 Soft Sales

Case Illustration In 1996, the SEC charged Advanced Medical Products employees with recognizing revenues on “soft sales” or sales for which the customer had expressed interest but not actually committed to purchasing. The company shipped the products to its field representatives, who held them while the customer decided whether to purchase the product.

The company however, recognized the revenue as of the date of the shipment to the field representative. Employees withheld sending invoices and monthly statements to prevent customer complaints resulting from being invoiced for equipment that they had not agreed to purchase.

To detect this scheme, the auditor may wish to review customer complaint logs and correspondence for complaints of goods shipped prior to the customer’s readiness to accept or when the customer was merely making inquiry into the goods.

5.5.3 Contracts With Multiple Deliverables

Another common scheme occurs when companies ship product or equipment to customers who are not obligated to pay for such equipment until it is “accepted.” Acceptance typically requires a seller to substantially complete or fulfil all the terms of an arrangement before delivery is deemed to have occurred. Common customer acceptance provisions included in contracts that, if not satisfied by the seller, would preclude recognition include: Seller’s obligation to perform additional services subsequent to the delivery, e.g., product installation and activation; Product testing prior to payment; and Training of personnel with respect to produce use.

24 FIRST DRAFT

If a contract requires the seller to provide “multiple deliverables” or elements, the delivery is not deemed complete unless substantially all elements or deliverables are delivered. The sales revenue should be recognized only if inconsequential elements remain to be delivered.

When assessing whether revenue can be recognized prior to delivery of all required elements or deliverables, the criteria under GAAP is whether the undelivered portion is “essential to the functionality” of the total deliverable. 27 SAB 101 enumerates several factors that should be considered in determining whether remaining performance obligations are substantial or inconsequential.28

Case Illustration The SEC action against Advanced Medical Products is a classic example of improperly recognizing revenue on contracts with multiple deliverables. 29 Rather than shipping the product to the customer, Advanced Medical Products shipped products to company’s field representatives, who were responsible for installing the product and training the customer’s employees. The SEC charged that the company incorrectly recognized revenue upon shipment to the field representatives. This policy contravened GAAP as there was no economic exchange and risk of loss had not passed to the customer because the products were still in the control of the company.

In addition to the general indicators listed above, this scheme, which has been prevalent in the software industry, can possibly be uncovered by confirming with major customers whether all services have been performed with respect to the products purchased and received. For companies that deal with distributors of their product, auditors should obtain an understanding as to whether the company “forces” a pre-determined listing of SKUs to its distributors, without an order from the distributors. If this is the case, there may be a culture of forcing product out to distributors to ‘meet the numbers.’ A rash of returns from the

25 FIRST DRAFT distributors in subsequent months might also reveal this practice. Further manipulation of the books and records can occur by the entity when these returns are not processed in a timely fashion.

5.5.4 Up-Front Fees

Some firms will collect up-front fees for services provided over an extended period, e.g., maintenance contracts. SAB 101 provides that up-front fees should generally be recognized over the life of the contract or the expected period of performance.

5.6 Bill and Hold Transactions

“Bill and Hold” schemes are another common method of bypassing the delivery requirement. As its name implies, a legitimate sales order is received, processed, and ready for shipment. The customer however, for whatever reason, may not be ready, willing, or able to accept delivery of the product at that particular point in time. The seller holds the goods in its facility or ships them to a different location, such as a third party warehouse for storage until the customer is ready to accept shipment.

The seller however, recognizes revenue immediately upon shipment. The auditor must consider whether the seller has met (or is seeking to circumvent) enumerated specific criteria established by the SEC30, including whether: Risk of ownership has passed to the buyer; Customer has made a fixed commitment to purchase the goods, preferably in written documentation; Buyer must request that the transaction be on a bill and hold basis; Buyer must have a substantial business purpose for ordering the goods on a bill and hold basis; Delivery must be fixed and on a schedule that is reasonable and consistent with the buyer's business purpose; Seller must not retain any specific performance obligations under the agreement such that the earning process is not complete;

26 FIRST DRAFT

Ordered goods must be segregated from the seller's inventory and not be subject to being used to fill other orders; and Product must be complete and ready for shipment.

In addition to the above factors, the SEC also recommends preparers of financial statements to consider:

The date by which the seller expects payment, and whether the seller has modified its normal billing and credit terms for this buyer; The seller's past experiences with and pattern of bill and hold transactions; Whether the buyer has the expected risk of loss in the event of a decline in the market value of goods; Whether the seller's custodial risks are insurable and insured; and Whether extended procedures are necessary in order to assure that there are no exceptions to the buyer's commitment to accept and pay for the goods sold (i.e., that the business reasons for the bill and hold have not introduced a contingency to the buyer's commitment).31

Auditors coming across agreements that do not meet the above criteria should be wary of potential bill and hold schemes. Auditors should consider whether: Bills of lading are signed by a company employee rather than shipping company; Review of shipping documents indicates excessive shipments made to warehouses rather than to a customer's regular address (which could mean that shipments are made to the seller’s warehouses rather than customer locations); Shipping information is missing on invoices; High shipping costs incurred near the end of the accounting period; Large, numerous or unusual sales transactions occurring shortly before the end of the period; or Decrease in current year monthly sales from the prior year that may indicate the reversal of fraudulent bill and hold transactions in a subsequent period.

When confronted with the above indicators, the auditor should first inquire of management regarding any bill and hold policies and any customers with bill and hold arrangements. The auditor should also make inquiry of warehouse personnel regarding “customer” inventory being held on the premises in a third party warehouse, or shipped to another company facility. Finally, the auditor should inquire of shipping department or finance personnel if they have ever been asked to falsify or alter shipping documents.

27 FIRST DRAFT

If additional investigation is warranted, the auditor should review the customer contracts to determine whether they meet the requirements of SAB 101 enumerated above. The auditor should also: Review underlying shipping documents for accuracy and verify existence of transactions; Compare shipping costs to prior periods for reasonableness. Review warehouse costs and understand the business purpose of all warehouses owned/used by the company; Confirm special bill and hold terms with customers directly including transfer of risk of loss and liability to pay for the bill and hold goods; Test reconciliation of goods shipped to goods billed for accuracy; Select a sample of sales transactions from the sales journal, obtain the supporting documentation and - Inspect the sales order for approved credit terms; - Compare the details among the sales orders, shipping documents and sales invoices for inconsistencies; - Compare the prices on sales invoices against published prices; and - Re-compute any extensions on sales invoices; and In conjunction with the physical inventory, tour the facility or warehouse and inquire of warehouse personnel about any held customer products.

Case Illustration

In 2003, the SEC charged Anika Therapeutics with improperly recognizing approximately $1.5 million in revenue form a bill and hold transaction. A distributor placed orders with Anika for a total of approximately 15,000 units of a particular product in April and July 1998. As part of the agreement with the distributor, Anika invoiced the distributor for the total 15,000 units for over $500,000 in September 1998 but held the product at Anika’s refrigerated facility until the distributor requested the product, which did not occur until March 1999. However, Anika recorded the revenue for this sale in the quarter ended September 30, 1998. 32

28 FIRST DRAFT

5.7 Fictitious Revenue Schemes

Schemes to create fictitious revenues, as opposed to prematurely recognize revenue, cross the line between the potentially defensible and the completely indefensible.

5.7.1 Fictitious Sales to Existing or Non Existent Customers

A common technique to overstate revenues is to create fictitious orders either for existing or fictitious customers. These schemes involve the preparation of false supporting documentation to provide “backup” to non-existing sales or services never rendered.

Fictitious revenue schemes can and often will be detected by the same methods used to detect premature revenue recognition schemes. Auditors should consider: Discovery of significant revenue adjustments to revenue at the end of the reporting period; Unexpected increases in sales by month at period end; Customers with unknown names or addresses or which have no apparent business relation to the business; Increased sales accompanied by stagnant or decreasing cost of sales and corresponding improvement in gross margins; Improvement in bad debts as a percentage of sales; and/or Decrease of shipping costs compared with sales.

Fictitious revenue schemes are relatively easy to investigate, once detected. The audit or investigative team should focus on accounting personnel and inquire whether:

Revenues are recorded outside of the normal invoicing process, or standard monthly journal entries; Journal entries have adequate, proper and bona fide supporting documentation; Accounting personnel have been pressured to make or adjust journal entries; and

29 FIRST DRAFT

Accounting or sales personnel have been pressured to create false invoices for existing or fictitious customers.

The auditor should also inquire whether sales or shipping personnel have noted any unusually high sales or shipments to customers with no reasonable explanation or noted any significant sales or shipments to unfamiliar new customers.

Auditors should also consider the following detection procedures:

Send confirmations to customers who may be associated with suspicious transactions; Perform alternative procedures for confirmations not returned or returned with material exceptions such as: - Including other matters on the confirmations such as any consigned inventories held at the customer location or held for the customer; and - Including amount of pending returns on the confirmation as a blank line for the customer to complete. Review journal entries and supporting documentation, and verify their accuracy; Identify amount of returns in subsequent period; Look for sales which reverse in the subsequent period; and Conduct research of publicly available information (e.g., on-line database, manual record and Internet) to verify existence and legitimacy of customers. Follow up physical visits may also be prudent.

Case Illustration Consider the case of medical device supplier, Boston Japan33, which during fiscal years 1997-1998 recognized over $75 million dollars of revenue from fraudulent sales. Company sales managers leased commercial warehouses, recorded false sales to distributors, and shipped the goods to the leased warehouses. The company masked the fact that the distributors never paid for the goods by issuing credits to the distributors and then recording false sales of the same goods to other distributors, without ever moving the goods out of the leased warehouses.

Company employees even recorded sales to distributors that were not involved in the medical device business, but that had agreed with company sales managers to collude in the fraud. Some of the false sales were made to

30 FIRST DRAFT distributors that never resold any of the goods and never paid Boston Japan for any purported sales. The sales managers and cooperating independent distributors further colluded to cover up false sales by falsely confirming the legitimacy of the sales to the company’s auditors.

5.7.2 Round Tripping

Round tripping consists of recording transactions that occur between companies for which there is no economic benefit to either company. For example, a company that provides a loan to a customer so that the customer can purchase the product engages in round tripping if the loan was issued with no real prospect that the customer will ever repay the loan. These transactions are deemed completed for the sole purpose of inflating revenue and creating the appearance of strong sales.

Round tripping recently has occurred extensively in the telecommunications and oil and gas industries. For example, numerous telecommunication companies boosted their sales volume by exchanging the indefeasible rights of use on their fiber-optic networks to other telecommunications companies (this practice was known in the industry as “capacity swaps.”) These transactions were sometimes booked as income even though the swaps generated no net cash for either company.

Case Illustration

In 2002, the SEC began investigating the way telecom giant Qwest Communications International Inc. and some of its competitors, such as Global Crossing accounted for sales of fiber-optic capacity and whether it was proper for the company to recognize the revenue right away immediately.

Qwest sold capacity on their fiber-optic network to carriers and also purchased capacity from them. Both companies recognized revenue from capacity swaps

31 FIRST DRAFT and indefeasible rights of use (“IRU”) that allowed another carrier or company the unfettered use of the capacity over a long period of time. In some cases, the amount of the sale and purchase were almost identical. Qwest booked the revenue from these sales all at one time instead of deferring part of it over many years. GAAP however, requires companies to record the revenue generated by an IRU over the time of the contract. The effect was to boost Qwest's revenue by $1 billion in 2001 and $465 million in 2000.

Since most roundtrip transactions involve counterparties in the same line of business, an auditor should review a list of the company’s significant customers. If there is a customer in the same line of business, the auditor should scrutinize the transactions for evidence of any round tripping. The auditor should also review the vendor list and compare it to the customer list. The same company appearing on both lists might indicate round tripping. There is always the possibility of an intermediary being involved in the transaction, so an auditor should be aware of companies that appear on the two lists but would not be valid customers or vendors. Round tripping often takes place with related parties so the auditor should be aware of related party transactions and follow the steps outlined in Section 5.9.5

5.8 Other Improper Recognition Schemes

5.8.1 Recognizing Revenue On Disputed Claims Against Customers

Reasonable assurance of payment is basic to revenue recognition. Companies sometimes circumvent this requirement by recognizing the full amount of revenue even though the customer has for some reason disputed payment. Auditors should inquire as to all receivables that are in dispute and, if necessary, confer with legal counsel for the company to assess whether collection of the revenue is sufficiently certain to be able to be properly recognized.

32 FIRST DRAFT

5.8.2 Holding The Books Open Past the End of a Period

Improperly holding open the books beyond the end of an accounting period can enable companies to record additional end of period sales that are invoiced and shipped after the end of a reporting period. While standard cut-off testing will often discloses these schemes, auditors should be cognizant and skilled in detecting manipulation of information systems to achieve this result. Direct inquiry of accounting personnel, billing clerks and warehouse personnel may assist in determining whether the books are held open past the end of the period. Computer forensics can also be used to ferret out these schemes.

Case Illustration In 1993, the management of Platinum Software Corp., was concerned about the company’s "days sales outstanding" ("DSO") – the measure of the time a company takes to collect its receivables. The company’s DSO had increased throughout 1993, in part because it had improperly recognized revenue on contingent or cancelled license agreements. One of the company’s responses to the increasing DSO was to hold open the company’s open for cash received after period-end. Management recorded checks received by the company in July 1993, on the company’s balance sheet as an increase in cash and a reduction in receivables as of June 30. Holding the books open resulted in a cash overstatement and associated receivable understatement. Similarly, for the quarter ending September 1993, management included cash that the company received for about a week into October, resulting in a cash overstatement and accounts receivable understatement of $724,000. The same pattern continued through December 1993, resulting in a cash overstatement and accounts receivable understatement of $3,463,000. The company was ultimately ordered to cease and desist in this practice by the SEC.

5.8.3 Recognizing Income on Consignment Sales or Products Shipped for Trial/Evaluation Purposes

33 FIRST DRAFT

SAB 101 prohibits revenue recognition from consignment arrangements until completion of actual sale. The same criteria apply to products delivered for demonstration purposes. 34 The reason for this is that in a typical consignment arrangement, neither title nor the risks and rewards of ownership pass from the seller to the buyer. Consignment sales and sales shipped under trial or evaluation purposes are thus merely specific examples of contingent events which must be satisfied before revenue can be recognized. Particular attention must be paid to the terms, facts and circumstances of any agreement in which: The buyer has the right to return the product and - Buyer does not pay the seller at the time of sale, and the buyer is not obligated to pay the seller at a specified date or dates; - Buyer does not pay the seller at the time of sale but rather is obligated to pay at a specified date or dates, and the buyer’s obligation to pay is contractually or implicitly excused until the buyer resells the product or subsequently consumes or uses the product; - Buyer’s obligation to the seller would be changed (e.g., the seller would forgive the obligation or grant a refund) in the event of theft or physical destruction or damage of the product; - Buyer acquiring the product for resale does not have economic substance apart from that provided by the seller; or - Seller has significant obligations for future performance to directly bring about resale of the product by the buyer; and - The product is delivered for demonstration purposes.35

Case Illustration

In the second quarter of 1998, FLIR Systems inappropriately recognized $225,000 in revenue relating to a consignment sale. The purchase order submitted by the FLIR’s customers stated “…payment for each system to be made when a system is sold by [the customer] to an outside customer.” Despite these words, FLIR recognized revenue from this sale, even though no end-user was ever identified at the time of the purchase order.36

5.8.4 Contract Accounting Schemes

GAAP provides for contract revenue to be recognized using either the percentage of completion or completed contract method. The percentage of

34 FIRST DRAFT completion method applies only if management can reliably estimate progress toward the completion of a contract; that is; management must be able to estimate reliably the total costs required to complete the contract. 37 Conversely, GAAP requires the "completed contract" method when management cannot reliably estimate progress toward completion. The completed contract method requires the company to postpone recognizing revenue until the contractual obligations have been met.38

The percentage of completion is the method that is most often subject to abuse. Some companies will use the percentage of completion method notwithstanding that they do not qualify for that method. Companies can artificially inflate revenue by increasing the costs incurred toward completion, underestimating the costs of completion, or overestimating the percentage completed.

The auditor should perform the following procedures when performing an audit or investigation of contracts: Select a sample of contracts and confirm: o Original contract price; o Total approved change orders; o Total billings and payments; o Details of claims; o Back charges or disputes; and o Estimated completion date. Ensure that all incurred costs are supported with adequate documentation detailing the nature and amount of expense; Audit estimated costs to complete by reviewing estimates and comparing with actual costs incurred after the balance sheet date; Ensure that all estimated costs to complete the contract should be supported by reasonable assumptions; Ensure that all contracts are approved by appropriate personnel; Review unapproved change orders; Identify unique contracts and retest the estimates of cost and progress on the contract; Test contract costs to ensure costs are matched with appropriate contracts and costs are not shifted from unprofitable contracts to profitable ones; Ensure that losses are recorded as incurred;

35 FIRST DRAFT

Review all disputes and claims; Visit the construction contract site to view the progress of a contract; and/or Interview project managers, subcontractors, engineering and technical personnel to get additional information on the progress of an engagement and the assumptions behind the contract.

Case Illustration In 1996, the SEC charged 3Net Systems with improperly recognizing over $1 million of revenue in both 1991 and 1992, by misrepresenting to its outside auditors the degree to which certain work had been completed under certain contracts with existing customers. In fact, 3Net had not completed any of the contracts, and in addition, had not even determined the costs to complete. Further, 3Net had no other means of reliably estimating progress toward completion for these contracts, as it lacked the systems necessary to estimate and track progress on their development. Because 3Net could not reliably estimate progress toward completion, the contracts in question did not qualify for the percentage of completion method. The SEC charged 3Net should have used the completed contract method for the contracts. Had it done so, 3Net would not have reported revenue in fiscal 1991 because it completed none of these contracts by the end of fiscal 1991.39

5.8.5 Sham Related Party Transactions

Sham related party transactions are transactions between related parties where either little or no consideration is given for the product or service. The existence of related party transactions cuts to the very first criteria of SAB 101 that there be persuasive evidence of an arms length arrangement. Sales transactions should stem from express or implied contracts and represent exchanges between independent parties at arm’s-length prices and terms. Accordingly, arms-length transactions cannot be achieved in those situations where the parties are related or where one party can exercise substantial control over the other.

36 FIRST DRAFT

Related party transactions carry the presumption that one or both parties have received a benefit that they would not have otherwise received had the transactions been truly arms length. Related party schemes can take place in the context of any of the schemes listed in this chapter.

Transactions between related parties are often difficult to audit as these transactions are not always accounted for in a manner that communicates their substance and effect with transparency. The possibility of collusion always exists given that the parties are, by definition, related. Internal controls, moreover, might not identify the transactions as involving related parties.

An auditor may encounter related parties that are known by some members of the company; however, the relationships are not properly disclosed in the books and records. The auditor should inquire as to outside business interests and then try to determine whether they are properly disclosed, and the volume of transactions, if any, that are occurring between the entities.

Auditors should also focus on the relationship and identity of the other party to the transaction and whether the transaction emphasizes form over substance. Common indicators of such related party, sham transactions include but are not limited to:

Borrowing or lending on an interest-free basis or at a rate of interest significantly above or below market rates; Selling real estate at prices that differ significantly from appraised value; Exchanging property for similar property in a non-monetary transaction; Loans with no scheduled terms for when or how the funds will be repaid.40 Loans with accruing interest differing significantly from market rates; Loans to parties lacking the capacity to repay; Loans advanced for valid business purpose and later written off as uncollectible;41 Non-recourse loans to shareholders; Agreements requiring one party to pay the expenses on the other’s behalf; Round tripping sales arrangements (seller has concurrent obligation to purchase from the buyer); Business arrangements where the entity pays or receives payments of amounts at other than market values;

37 FIRST DRAFT

Failure to adequately disclose the nature and amounts of related party relationships and transactions as required by GAAP42; Consulting arrangements with directors, officers or other members of management; Land sales and other transactions with buyers of marginal credit risk; Monies transferred to or from the company from a related party for goods or services that were never rendered; Goods purchased or sent to another party at less than cost; Material receivables or payables from to or from related parties such as officers, directors and other employees;43 Discovery of a previously undisclosed related party; Large, unusual transactions with one or a few other parties on or at period end; and Sales to high-risk jurisdictions or jurisdictions where the entity would not be expected to conduct business. . If related party transactions are detected or suspected, the auditor should consider further inquiry, including: Conducting public records searches/background investigations on customers, suppliers and other individuals to identify related parties and confirm legitimacy of business; Performing data mining to determine whether transactions appear on computerized files; Performing document review of identified transactions to obtain additional information for further inquiry; Searching for unusual or complex transactions occurring close to the end of a reporting period; Searching for significant bank accounting or operations for which there is no apparent business purpose; Reviewing the nature and extent of business transacted with major suppliers, customers, borrowers and lenders to look for previously undisclosed relationships; Reviewing confirmations of loans receivable and payable for indications of guarantees; Performing alternative procedures if confirmations are not returned or returned with material exceptions; Reviewing material cash disbursements, advances and investments to determine if the company is funding a related entity; Testing related party sales to supporting documentation (i.e., contract and sales order) to ensure appropriately recorded; Discussing with counsel, prior auditors and other service providers the extent of their knowledge of parties to material transactions; and Inquiring about side agreements with related parties for right of return or contract cancellation without recourse

38 FIRST DRAFT

6. Asset Overstatement/Liability Understatement Schemes

Improper reporting of assets is another way for companies to overstate earnings. A direct relationship exists between overstatement of assets/understatement of liabilities on the balance sheet and the inflation of earnings. The WorldCom scandal for example, exemplifies how expenses improperly capitalized as assets on the balance sheet can serve to inflate income. In many cases, perpetrators are looking for a place on the balance sheet to place the debit. Overstating an asset or understating a liability usually occurs with this scheme. Accounts such as inter-company and foreign currency exchange gain/loss should not be overlooked as potential places to hide the debit.

Common asset overstatement fraud schemes include: Creating fictitious assets; Manipulating balances of legitimate assets with the intent to overstate value; Understating liabilities or expenses, including failing to record (or deliberately under estimating) accrued expenses, environmental litigation liabilities and other business problems; Misstating inter-company expenses; and Manipulating foreign currency exchanges.

An auditor can often become alert to the possibility of fictitious or over inflated assets by inquiring as to whether the entity intends to secure financing. If the answer is yes and if that financing is contingent on the value of particular assets such as receivables or inventory, that should lead the auditor to ask more questions and perform additional procedures to verify the existence, and location and value of these assets. As with certain other schemes, the auditor can most often detect these schemes by observing the company’s operations and inquiring as to unusual items.

6.1 Inventory Schemes

39 FIRST DRAFT

The original COSO Report found that fraudulent asset valuations comprised nearly half of the cases of financial fraud statements. Misstatements of inventory, in turn, comprised the majority of asset valuation frauds.

Generally, when inventory is sold, the amounts are transferred to cost of goods sold and included in the income statement as a direct reduction of sales. An overvaluation of ending inventory will understate cost of goods sold and in turn, overstate net income.

Inventory schemes can generally fall into three categories: Artificially inflating the quantity of inventory on hand; Inflating the value of inventory by - Postponing write-downs for obsolescence); - Manipulating unit of measurement to inflate value; - Under-reporting reserves for obsolete inventory, especially in industries where products are being updated or have a short shelf life; and - Changing between inventory reporting methods (average costing, last invoice price, LIFO, FIFO, etc.); Fraudulent or improper inventory capitalization.

Following are indicators an auditor can look for to detect possible inventory manipulation: A gross profit margin which is higher than expected; Inventory that increases faster than sales; Inventory turnover that decreases from one period to the next; Shipping costs that decrease as a percentage of inventory; Inventory as a percentage of total assets that rise faster than expected; Decreasing cost of sales as a percentage of sales; Cost of goods sold per the books that do not agree with the company's tax return; Falling shipping costs while total inventory or cost of sales have increased; and Monthly trend analyses that indicate spikes in inventory balances near year-end.

6.1.1 Inflating Inventory Quantity (Fictitious Inventory)

40 FIRST DRAFT

The simplest way to overstate inventory is to add fictitious items to inventory. Companies can accomplish this by creating fake or fictitious: Journal entries; Shipping and receiving reports; Purchase orders; and Quantities on cycle counts or physical counts.

Some companies even go as far as maintaining empty boxes in a warehouse.

The most effective way for the auditor or auditor to confirm the inventory balance is physically to observe the client’s inventory, particularly at times when an inventory count is being performed. In fact, Generally Accepted Auditing Standards (“GAAS”) require auditors to physically observe, test, and inquire as to the amount of inventory on hand and to satisfy themselves with respect to the methods of inventory taking and the measure of reliance placed upon the client’s representations about the quantities and physical condition of inventories.44 When the auditor cannot be satisfied as to the inventories he or she must physically count the inventory and test transactions in that account.45 Where inventory is stored outside the company site, such as public warehouses, auditors should conduct additional procedures to confirm balance.

Case Illustration Fraud history is filled with names of companies made famous or infamous by fictitious inventory schemes including McKesson and Robbins, ZZZ Best and Crazy Eddie. The most famous bogus inventory fraud perhaps is the “Salad Oil Swindle” of the 1960s. In that case, management of the company rented petroleum tanks and filled them with seawater. The company was able to convince the auditors that the tanks contained over $100 million in vegetable oil because the oil rose to the top of banks. In fact, the little oil that was present was pumped from one tank to the next depending on the company’s advance knowledge of the auditor’s inventory observation plan.46

41 FIRST DRAFT

The auditor should look for the following operational factors may arouse suspicions of fictitious inventory: Inventory that cannot be easily physically inspected; Unsupported inventory, cost of sales or accounts payable journal entries; Unusual or suspicious shipping and receiving reports; Unusual or suspicious purchase orders; Large test count differences; Inventory that does not appear to have been used for some time or that is stored in unusual locations; Large quantities of high cost items in summarized inventory; Unclear or ineffective cut-off procedures or inclusions in inventory of merchandise already sold or for which purchases are not recorded; Adjusting entries which have increased inventory over time; Material reversing entries to the inventory account after the close of the accounting period; Inventory that is not subject to a physical count at year end; Improper or “accidental” sales that are reversed and included in inventory but not counted in physical observation (for example a company “accidentally” delivers a specifics product to a customer, tells the customer it was a mistake and requests the customer to send the product back); and Excessive inter-company and interplant movement of inventory with little or no related controls or documentation.

Even physical observation however, is not fail-proof. Even when an auditor can observe inventory, a company can still perpetrate fraud by: Following the auditor during the course of the count and adding fictitious inventory to the items not tested; Obtaining advance notice of the timing and location of the inventory counts thereby permitting the company to conceal shortages at locations not visited; Stacking empty containers at the warehouse which are not checked during the count; Entering additional quantities on count sheets, cards, scanners, etc. that do not exist or adding a digit in front of the actual count; Falsifying shipping documents to show that inventory is in transit from one company location to another; Falsifying documents to show that inventory is located at a public warehouse or other location not controlled by the company; Including consigned items as part of the inventory count; and Including items being held for customers as part of the inventory count.

42 FIRST DRAFT

To deter management from inflating inventory during physical counts, the auditor should consider: Reviewing company policy for inventory counts (frequency and procedures); Inquiring of management and internal audit as to the dollar adjustment of the book to physical counts and the reasons for the significant differences; Inquiring as to whether all inventory shrinkages have been reported; Inquiring and observe inventory at third-party locations/off-site storage locations; Observing a physical inventory unannounced; and Conducting physical inventories for multi –locations all on the same date.

6.1.2 Inflating Inventory Value