The New York Times March 24, 2012 In Europe, Where Art Is Life, Ax Falls on Public Financing

By LARRY ROHTER

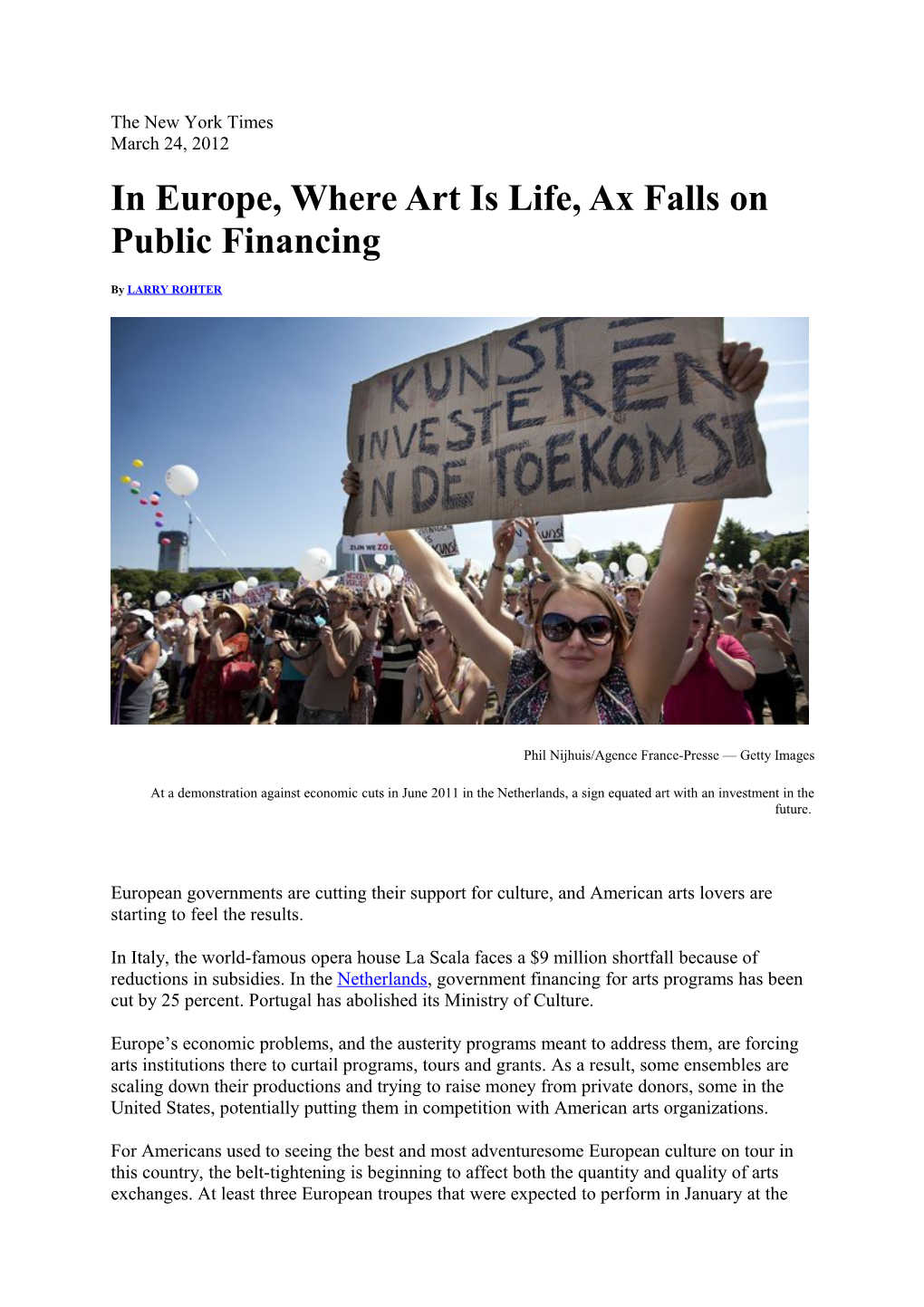

Phil Nijhuis/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

At a demonstration against economic cuts in June 2011 in the Netherlands, a sign equated art with an investment in the future.

European governments are cutting their support for culture, and American arts lovers are starting to feel the results.

In Italy, the world-famous opera house La Scala faces a $9 million shortfall because of reductions in subsidies. In the Netherlands, government financing for arts programs has been cut by 25 percent. Portugal has abolished its Ministry of Culture.

Europe’s economic problems, and the austerity programs meant to address them, are forcing arts institutions there to curtail programs, tours and grants. As a result, some ensembles are scaling down their productions and trying to raise money from private donors, some in the United States, potentially putting them in competition with American arts organizations.

For Americans used to seeing the best and most adventuresome European culture on tour in this country, the belt-tightening is beginning to affect both the quantity and quality of arts exchanges. At least three European troupes that were expected to perform in January at the Under the Radar theater festival in New York, for example, had to withdraw as they could not afford the travel costs, and the organizers could not either.

“It is putting a pretty serious crimp in international exchanges, especially with smaller companies,” said Mark Russell, artistic director of Under the Radar. “It’s a very frustrating environment we’re in right now, tight in part because of our own crash, but more generally because it seems to me now that every time we get around to the international question, we have a meltdown and go back to zero.”

For artists and administrators in Europe, such changes are deeply disquieting, even revolutionary. In contrast to the United States, Europe has embraced a model that views culture not as a commodity, in which market forces determine which products survive, but as a common legacy to be nurtured and protected, including art forms that may lack mass appeal.

“Culture is a basic need,” said Andreas Stadler, director of the Austrian Cultural Forum in New York and president of the New York branch of the European Union National Institutes for Culture. “People should have the right to go to the opera.”

Over all, he added, “Culture is much higher on our political agenda than it is here, because it is so linked to our identities.”

Germany and France, the largest and most stable economies in Europe, are suffering the least and can even point to increases in financing for some officially favored programs, genres and ensembles that are seen as promoting the countries’ images abroad, like film.

But other countries with governments that are led by conservatives or technocrats — like Italy, Hungary, the Netherlands and Britain — have had their culture budgets slashed. So have others that are being forced to cut public spending to remain in the euro zone, including Greece, Portugal, Spain and Ireland.

In the case of the Netherlands, the culture budget is being cut by about $265 million, or 25 percent, by the start of 2013, and taxes on tickets to cultural events are to rise to 19 percent from 6 percent, although movie theaters, sporting events, zoos and circuses are exempted. The state secretary of education, culture and science, Halbe Zijlstra, has described his focus as being “more than quality, a new vision of cultural policy,” in which institutions must justify what they do economically and compete for limited funds.

In practical terms, that has meant that smaller companies, especially those engaged in experimental and avant-garde efforts, bear the brunt of the projected cuts. Large, established institutions, like the Rijksmuseum, the van Gogh Museum, the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra and the Dutch National Ballet, are in a better position to fend for themselves.

“The economy is not that good any more, so to get support, you have to be a large company with an international reputation,” said Michael Nieuwenhuizen, the senior project manager for international affairs of the Netherlands Music Center. “Plus, the government wants to see value for the money and links that to the markets, so that if you have an audience, you get rewarded.”

As a result, he added, “we’re going to lose some orchestras and choirs.” And in the dance field, said Sophie Lambo, managing director of the Internationaal Danstheater, of Amsterdam, “it’s going to be a tsunami.”

In the boom years before the economic crisis hit late in 2008, it was not uncommon for touring European orchestras, ballet and opera companies and theater troupes to travel beyond New York, to cities like Minneapolis and San Diego. That has now become more difficult, and when it occurs, the European performers expect their American hosts to cover more of the costs.

“We have less money and have changed our concept of cooperation,” said Mr. Stadler of the group of European cultural institutes, which has 44 members. “We expect more from our partners and we will negotiate tougher.”

The cutbacks are hitting so hard that some of the cultural institutes in New York that have been intermediaries for arts companies in their home countries have experienced reductions of staff or salary, or both.

The crisis is also affecting what kind of art is performed and how it is made. After returning from Europe last month, Nigel Redden, director of the Lincoln Center and Spoleto arts festivals, said that a trend toward new work with fewer characters or players, especially with commissioned pieces, seemed to be growing.

“Many playwrights are writing things for three performers instead of eight, and if you are a composer, you may be writing for a chamber group rather than a symphony,” he said. “That also is a factor of the current climate: artists want to have their work performed, and smaller productions are inevitably less expensive to put on.”

Some of those scaled-down works are now beginning to find their way to the United States. The lineup for this summer’s Lincoln Center Festival, announced last week, includes “Émilie,” a 2010 “monodrama” opera for a single singer, written by the Finnish composer Kaija Saariaho, which had its American premiere last year at Spoleto.

In New York, European arts institutions are also looking for smaller, less expensive places to present their offerings. “Why spend so much money on Carnegie Hall when there are cheaper places available?” one organizer of cultural exchanges said, insisting on anonymity so as not to jeopardize business ties.

Others are trying to forge closer ties to American institutions. The Romanian Film Festival, which has done much to promote awareness of the Romanian new wave of prizewinning directors and actors, was presented last year at Lincoln Center with the Film Society of Lincoln Center as a co-sponsor.

“Compared to five years ago, we no longer think of doing things alone, on our own” said Corina Suteu, of the Romanian Cultural Institute. “All of a sudden, you have to become creative, you need to look for partners, whether American, European or even from other continents. I’m doing this, and all of my colleagues are doing the same.”

As they scramble to stay afloat, affected institutions in Europe are also cultivating private donors anywhere they can be found. But with little experience with, or understanding of, that kind of fund-raising, they often turn for advice to the American institutions with which they have built longstanding affiliations. “I can tell you that across the board, they are talking about their governments saying that they are going to have to move toward an American model,” said Joseph V. Melillo, executive producer of the Brooklyn Academy of Music. “But there’s no tradition of individual philanthropy in many of these cultures, and so they lack both the motivation and tax incentives to give.”

As a result, some European arts institutions have begun looking for financial support in the United States, courting American companies or wealthy Americans with emotional ties to an ancestral homeland. But that means, as Mr. Stadler acknowledged, that “we are also competing with American institutions, which are also hit hard.”

Artists worry that money will flow to established entities that tend to be more conservative, rather than to more experimental companies that have served as incubators of new talents. That, they say, has profound implications for the artistic process.

The established companies “need to refresh their work by working with younger artists, and it’s the small and middle-sized companies that bring diversity and innovation,” said Ivana Müller, a choreographer based in Amsterdam. “You’ve created a different dynamic of production now,” she added, “and A lot of good work will disappear because it can’t sustain itself.”

Even when the crisis subsides, many fear that the impact of the cuts could permanently affect every stage of the artistic process, from creation to consumption.

“Perhaps instead of doing Brian Friel, one does Noël Coward, because the box office is important,” said Mr. Redden, the festival director, trying to put himself in the place of his European counterparts. “Some of these trade-offs are inevitable, but I think that if it becomes all drawing room comedies and not gritty theater, it would be devastating. It has not gotten to that yet, but there is definitely a kind of calibration going on.”