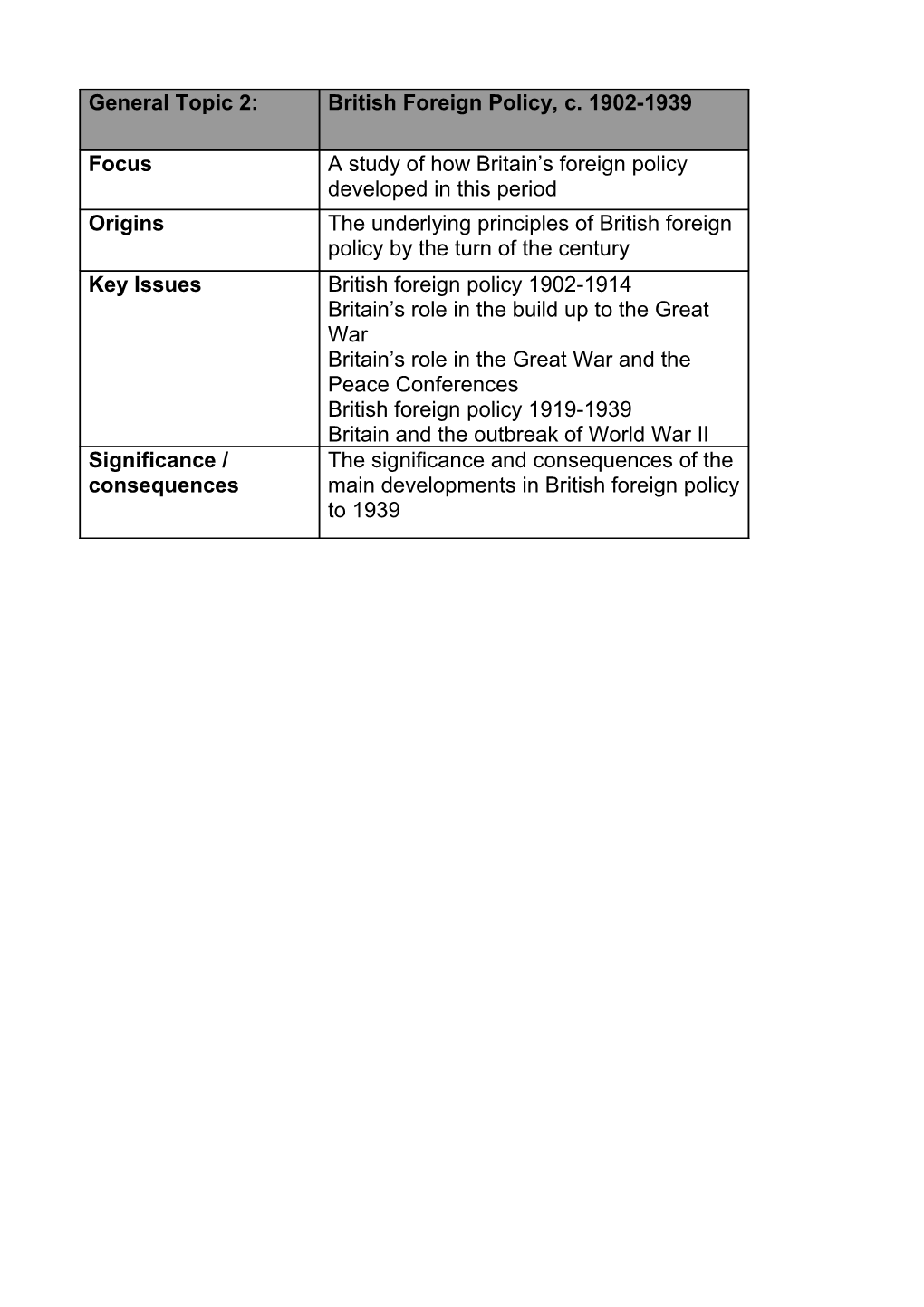

General Topic 2: British Foreign Policy, c. 1902-1939

Focus A study of how Britain’s foreign policy developed in this period Origins The underlying principles of British foreign policy by the turn of the century Key Issues British foreign policy 1902-1914 Britain’s role in the build up to the Great War Britain’s role in the Great War and the Peace Conferences British foreign policy 1919-1939 Britain and the outbreak of World War II Significance / The significance and consequences of the consequences main developments in British foreign policy to 1939 British foreign policy by the turn of the century

Lord Salisbury’s description of British foreign policy in the late nineteenth century was:

“….. to float lazily downstream, occasionally putting out a diplomatic boathook to avoid collisions.”

Britain did not commit itself to foreign countries. Salisbury, who had been Foreign Secretary and Prime Minister during this period, considered war to be “the final and supreme evil”. He hoped to solve disagreements with a diplomatic approach. He believed that membership of an alliance or aggressive behaviour would lead to war. The policy he adopted was called “splendid isolation”, or “limited liability” according to Robert Taylor. He was willing to form some pacts with other countries. In 1890, the borders between Mozambique and the areas under British control in Africa together with France’s control of Madagascar were confirmed. German sovereingty in Tanganyika and Heligoland was recognised. A pact was formed with the Italians regarding the borders between Eritrea and Sudan. Again, these pacts did not commit Britain to any military duty. Though it might be involved with other countries, Britain had no permanent link with them.

Initially it was possible to refer to the policy as a “splendid” one, but with time the policy became a burden and the isolation a disadvantage.

It was Britain’s prosperous position in industrial, military and commercial terms which allowed it to follow a policy of isolation in the late nineteenth century. By1900, Britain had the biggest empire ever seen. It included a quarter of the world’s population and covered more than twelve million square miles. Britain had by far the biggest navy and controlled the commerical world because of that. It was not practical for other countries to threaten it. Establishing an alliance was a sign of dependence on another country, and Britain did not need aid or support during this period. As Salisbury said:

“England does not solicit alliances; she grants them.” Britain believed that it was her responsibility to dominate other countries. Kipling’s description of this was “the white man’s burden” and it was its attitude towards foreigners, those people who were in his words “half-devil and half-child”, which kept them under strict control. Therefore, such a country was unlikely to acknowledge its need for assistance.

As British influence deteriorated, and as other countries overcame it in the commercial and military fields, Britain was forced to reconsider its foreign policy. As industrialisation swept through western countries, it was natural that there would be loss for Britain. Britain was no longer the only wealthy and prosperous power. Its contribution to world trade sank from 23% i 17%. Later on, it fell to 15%, as Germany’s percentage rose to 16% and that of the United States rose to 35%. The free trade policy was causing further problems. Chamberlain led a campaign in favour of protectionism. He felt that the rest of the world was gaining at Britain’s expense as other countries imposed tariffs on British goods whereas Britain refused to do the same to their goods.

Chamberlain introduced his new policy in May 1903. He said that it would lead to commercial prosperity and an increase in living standards. According to Milner, a campaigner for protectionism, “The ideals of our national strength and the confirmation of the empire would encourage domestic and social progress”. In his opinion contemporary patriotism was being:

“ choked in the squalor and shame of our large cities

But his ideas were opposed. Ordinary people thought that raising tariffs on other countries’ products would “tax our stomachs”. They would have to pay more for the goods that were tax-free at the time. Therefore, Britain rejected Chamberlain’s proposals, and its economy deteriorated. The country’s total exports fell from £234 million to £226 million in 1880. Another factor concerning the economy which caused much discontent and concern for Britain was its lack of mastery of the steel industry. In 1879, the two Welshmen, Gilchrist and Thomas, invented a method of using phosphoric minerals to produce steel. Before long 84 steelworks in Central and Western Europe were using the new method, and the process went over to the USA. After 1890, the USA was ahead of Britain in tems of its steel industry.

The USA was producing 9.3 million tons, and Britain only 8.0 million tons. By 1938, Britain’s total had risen to 10.5 million tons. But by then, output in the USA was 28.8 million tons, in Germany 23.2 million tons and in Russia 18.0 million tons. Clearly, Britain had lost hold of the reins. But, worse still, it was losing hold of its empire. As the power of the United States increased, Britain was alarmed at the idea of losing its naval bases in Canada and Latin America. As Russia extended its borders, Britain was afraid that its control of the Middle East and the Gulf would suffer. This could even lead to losing its control of India, the country described by David Omissi as “the jewel in the crown of the empire”. Certainly, British sovereignty was advantageous here because of the wealth of precious minerals, but it was even more important in that it confirmed British power outside the framework of Europe.

Britain also profited from Chinese trade, and any threat from another power in that country was a serious one. The “scramble” for colonies in Africa also meant that Britain would ultimately lose. Therefore Britain had fallen from its all-powerful and superior position, and it could acknowledge that other countries were equal to it. In order to stabilise its position, there was need to make agreements with other countries.

The power which appeared to be the greatest threat to Britain was Germany. Its contribution to world trade shot up from 8.5% in 1880 to 32% by 1913. The standard of education in Germany was exceptionally high, and this inevitably led to a growth in expertise. Even ordinary farmers were experimenting with chemicals in treating their plants to improve their fruitfulness. There were more crops per hectare in Germany than in any other country. AEG and Siemens were the most advanced electricity companies in the world. Bismarck described Germany as an “overloaded” country, a country without ambition which wanted to keep to the established order. But he later changed his attitude. It was clear that Germany could cope with the “burden of armament” more easily than any other country apart from Britain. By 1898, its navy had grown from being the sixth largest to being the second largest in the world.

The isolationism underlying British foreign policy was becoming unsuitable as Britain faced competition and threat from foreign countries.

Also, the tradition of moving further away from other countries had led to the isolation of Britain. All the other European powers belonged to an alliance. Bismarck, the German Chancellor, formed the Triple Alliance between Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy. Jameson’s raid in South Africa had caused much criticism in foreign countries. a member of the Hofmeyr family referred to this as a “crime”. Cecil Rhodes had led an attack on another state without a just reason. A telegram was sent by Kaiser Wilhelm II to Kruger congratulating him and his soldiers for resisting the British attack. If foreign countries were not angered by this case, they were angry following the Boer war. They sympathised with the Boers, especially after hearing of the “scorched earth” policy implemented in the country. This meant destroying the land in order to obstruct the Boers’ supply of food and establishing concentration camps for women and children to prevent them helping the men. The pugnacious Boers were referred to as “bitter-enders” in Britain, and these were admired abroad for their perseverance.

The issue of Venezuela also caused great discontent abroad. France felt hostile towards Britain anyway, because of its victories in Fashoda and West Africa. France was infuriated by Britain’s presence in Egypt. It looked as if Germany would be the only possible friend for Britain, but the arms race and Germany’s attitude towards Britain’s behaviour in relation to Jameson’s raid made any stable relationship unlikely.

Therefore, by the start of the twentieth century, the British felt that there was need to move away from the longstanding policy of isolationism.

Undoubtedly, by the start of the twentieth century it was neither practical nor wise for Britain to stand apart from other countries. Hatred abroad had intensified the need for Britain to commit itself to other powers. In abandoning its policy of “splendid isolation”, Britain was acknowledging its weakness.

Britain’s role in the build up to the First World War. The notes for this unit are on paper (reference 1) BRITAIN’S ROLE IN THE FIRST WORLD WAR

There is no doubt that the majority of the people at the start of the First World War felt that there was a short war ahead of them. They were thinking more in terms of weeks than years. The general belief was that “it would be over by Christmas”. The only person to state otherwise was the new Minister of War, Lord Kitchener, who told the Cabinet that he thought this war would take three years to win.

In fact when the Schlieffen Plan failed to overcome France quickly the outlook was black. Both sides began to “dig trenches” and any hopes of a short war were ended.

Initially the response to the war was very encouraging and people joined up in their thousands to receive “the king’s shilling”.

At the start of the war the Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith, refused to introduce military conscription in Britain. Kitchener knew that Britain needed a strong army, so he set about starting war propaganda in the hope of enticing young people to join the army voluntarily. Soon Britain was full of posters declaring “Your Country Needs You”, with the face of Kitchener himself staring at everybody.

The campaign was extremely successful and within a few days over 100,000 men had volunteered to enlist in the army. By September that figure had risen to over 500,000, and about a million had enlisted by February 1915. Britain was not on its own either as Canada and Australia sent 30,000 soldiers and New Zealand 8,500. This was the strong army Kitchener was going to sacrifice in order to achieve his task of winning the war.

The reasons why these men chose to join the war varied from person to person but on the whole the logic of the majority was quite weak.

Trench Warfare

As the men reached the western front they soon came to realise that it was not possible to defeat the German army quickly. Indeed it was seen that the armies were fairly equal and the warfare was quite immobile, in spite of the strenuous efforts of each side to gain an advantage over the other.

The trenches that were dug made traditional attack impossible really. With modern weapons, defending was much easier than attacking. The intention of the Germans was to defend the lands they had occupied, whereas Kitchener was trying to regain those lands and push Germany back towards the River Rhine. He knew from the start that the only way to do that was to attack and he set about trying to do that.

When the war began in August 1914, the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) was sent to France under the leadership of Sir John French to assist the French. Even though they were not large in numbers these soldiers were very important because the BEF managed to slow down the German attack on France. British soldiers fought their first battle at Mons in Belgium on 23 August 1914. The BEF faced the German 1 st Army under the leadership of General von Kluck, and even though the British were fewer in number they managed to prevent the Germans from capturing a large part of the Paris area. In the Battle of Marne in September, the French with British support managed to push the Germans back over the River Aisne and it was there that the Germans decided to dig the first trenches to ensure that they would not lose more ground.

That was the end of the quick war Germany had hoped to win, and the beginning of the fighting in the trenches which would cost so many lives.

The trenches spread from the banks of the Channel to the Alps, and the British Navy imposed a blockade on German ports. To defend the rest of the country the BEF went northwards to the region of Ypres in Belgium.

Ypres was facing attack by the German army which was advancing quickly towards it from the direction of Antwerp. This was the start of a series of huge and bloody battles at Ypres which would remain in the memories of so many soldiers who survived for the rest of their lives. In the first Battle of Ypres (October-November 1914) the British managed to halt the attack of the Germans but the losses were huge on both sides.

This in fact was the end of the BEF. Over half the soldiers were injured with one in ten of them being killed.

Kitchener set about trying to breach German lines at Neuve Chapelle in March 1915 and at Loos in September 1915 with little success. The Germans responded by attacking Ypres again (the second Battle of Ypres, April-May 1915). Neither side was able to break through and the reasons for this were obvious:

Why was victory so difficult?

A secret attack was impossible as there was need to bombard enemy lines constantly before attacking in order to clear the barbed wire in front of the trenches, and to create fear and terror among enemy soldiers ready for the attack. When that happened it was a clear signal to the other side that an attack was imminent.

Later came planes and balloons to be able to see the soldiers preparing behind the trenches. In some places the Germans had built an effective system of tunnels and the soldiers could hide in them until the bombardment was over.

At the time, however, the British did not know about these and so all the firing was often in vain.

Even if an attack managed to gain some ground, going further was often difficult as the bombardment had made the ground boggy and difficult to cross. In studying the plan of the trenches in France, it’s also clear that any ground gained would be a weak spot as it would be in the middle of a bend in the line of the trenches, or ‘salient’ as it was called, and so very open to attack from the side. In addition to this, more sophisticated fighting equipment made crossing no man’s land a difficult task if not impossible at times. The machine gun which could shoot 500-700 bullets a minute, the shells falling constantly, and poison gas were horrendous experiences soldiers had to face while walking through the mud towards enemy trenches. Very soon therefore the mobile warfare came to an end. In view of all this Lord Kitchener said, “I don’t know what to do. This isn’t war.”

It was at this time that Asquith decided to get rid of Sir John French as leader, appointing Sir Douglas Haig in his place. Haig knew full well what his task was, namely win the war, and he knew that would mean sacrifice and losses. This was a price he was willing to pay. The Trenches

During the first weeks of the war the generals on both sides were certain that the war would not last long. There was agreement on both sides that the war would be over by Christmas. The British newspapers were writing about soldiers on horseback annihilating the enemy and attacking Berlin within weeks.

That did not happen and to the soldiers old-fashioned warfare turned into the reality of modern warfare with weapons that could kill more quickly and in newer ways than ever before.

The trenches extended southwards from northern Belgium. The trenches were never straight, the soldiers realised very soon that if a shell exploded in a straight trench the damage would be huge, so the trenches were built in a zigzag manner. Between the British trenches and the enemy was No Man’s Land full of barbed wire to make attack difficult.

Life in these trenches was a nightmare to say the least.

The German trenches were usually quite a bit better than the British trenches. They were often linked by a system of underground tunnels and water pipes and there were fairly comfortable sleeping places in some of them. The aim of the Germans was to keep hold of the land they had won, so the trenches were designed for a long battle. On the other hand, Britain did not expect to be in the trenches very long, so the facilities were primitive at best.

The Battle of the Somme

One of the biggest battles during the war on the Western Front was the Battle of the Somme in 1916. In February 1916 the Germans decided to attack the French in the Verdun area. The response of the French was to promisie to defend the land to the last man if necessary. Sir Douglas Haig (Kitchener’s successor) decided that he would assist the French by organising his own attack on the Germans, thereby lessening the pressure on the French and also the Russians, as German soldiers moved from the Eastern Front to the Western Front. Therefore he organised an attack near the River Somme.

Haig’s campaign began on 1 July and it was a failure from the outset. The effort a fortnight before the attack to bombard German lines and clear the barbed wire was a failure. On that first day, British soldiers could not avoid the bullets of the Germans as they attacked. 21,000 soldiers died within a few hours and about 35,000 were injured. Nevertheless Haig decided to continue with the attacks until the middle of November. By then 418,000 British soldiers had been killed and 194,000 French soldiers, while Germany lost 650,000. Historians to this day continue to argue about the wisdom of these attacks. On the one hand Haig is called the “Butcher of the Somme”, but it must be remembered that the Battle of the Somme was a turning point in the war as it eventually broke German spirits.

The End

In December 1916 David Lloyd George became Prime Minister of Britain. From January 1917 onwards the war started to turn in Britain’s favour, and there are various reasons for this. The Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith, had introduced military conscription in February 1916 and that had been a strong psychological blow in favour of Britain. Britain had enough soldiers, but the purpose of military conscription was to send a clear message to Germany that Britain was going to fight to the end. This had a big impact on German spirits.

The Battle of the Somme (lesson 5)

By January 1917 Lloyd George had set up a special War Cabinet to deal with the war. The War Cabinet had 5 members – Lloyd George himself, Andrew Bonar-Law, Lord Curzon, Lord Milner and Arthur Henderson. This meant that Government decisions were more ordered and it was possible to co-ordinate policy much better, especially as Lloyd George created a secretariat for the Cabinet for the first time

In addition to this, Lloyd George arranged for talented individuals from outside the House of Commons to be appointed to important posts. Sir Joseph Maclay was made responsible for ships and Lord Beaverbook was the organiser of propaganda, while Lord Davenport was Director of Food and Sir George Prothero was responsible for increasing food production. These were businessmen and as organisers were second to none.

Germany had tried to starve Britain by using submarines to attack merchant ships which were bringing food into Britain. Although the plan was successful in the short term, it was not in the long term. Lloyd George organised escorts to protect the merchant ships. This, together with a little rationing in Britain, shattered Germany’s hopes of forcing Britain to ask for peace. Another result of Germany’s policy of sinking ships was its sinking of the Lusitania in 1915. This ship was travelling from New York to England and 1,198 people died when it was sunk by a German submarine. This incident played a leading part in the decision of the United States of America to join the war in February 1917. That country’s material contribution was critical and another psychological blow to Germany.

In April 1917 Canadian soldiers won an important battle at Vimy Ridge to the north of Arras, while British soldiers gained ground in the Ypres region. By then the British and French Generals had realised that there was no point attacking on an extended front and so started to fight for smaller peices of land at a time. This proved successful, and extensive use of the new weapon, the tank, in 1917 made that much easier too.

By early 1918 therefore Germany was facing intense problems. The biggest problem was that the soldiers’s spirits had been shattered. As well as the psychological blows against them, the naval blockade on the ports in German hands meant that food was getting more scarce for the soldiers at the front. In a final effort to change the situation General Ludendorff decided to organise one other huge attack. They managed to push Allied troops to within 40 miles of Paris. This was a temporary victory because the Allies organised a huge counterattack against the Germans, completely demolishing their lines.

The fighting continued for five weeks after that. The German leader, the Kaiser, fled to the Netherlands following the failure of Ludendorff’s plan, and when the German soldiers heard of that they had no desire to fight further. The German generals arranged a meeting with the chief generals of the Allies, and on 11 November 1918 an armistice was signed, and that without any British soldier setting foot on German soil.

The Peace Conferences and Foreign Policy 1919-1929 These notes are on paper (Reference 2)

Scan and place here Foreign Policy 1919-1939 Between 1919 and 1931, the international situation had improved gradually, and the hope of many people was that the world was on the verge of a period of permanent peace. Those hopes were shattered completely during the depression of the 1930s and in September 1939 war came to Europe again.

Why did this happen?

The first threat to international peace came in September 1931, when Japan began to extend its influence over Manchuria. The Chinese government appealed to the League of Nations and also to America as one of the countries that had signed the Briand-Kellogg Pact in 1928. This pact was signed by fifteen countries that agreed not to use war as a political weapon though they accepted that every country had the right to go to war to defend itself.

Neither America nor the League of Nations responded favourably to China’s case and Japan continued with its campaign to occupy Manchuria. In December 1931, the League of Nations decided to adopt economic sanctions against Japan. These steps were not very effective and in 1932 the troubles spread to Shanghai when the armed forces of China and Japan began a war. The war came to an end for a period because of the influence of America and Britain, but after Japan left the League of Nations in 1933 the League could do nothing to control its aggressive policies in China.

In the meantim, in January 1933 Hitler became Chancellor of Germany, beginning to extend the influence of the Nazi party over the lives of the Germans.

Once Hitler came to power, any hope that the Geneva disarmament conference would be successful disappeared. The western powers tried to form an agreement with Germany allowing it to re-arm under the control of the conference. Hitler refused to accept this offer and soon afterwards Gemrany decided to leave the conference in Geneva and also leave the League of Nations. In 1934 the disarmament conference was adjourned and any hopes of international disarmament ended.

In October 1935 Italy attacked Abyssinia (Ethiopia). Abyssinia appealed to the League of Nations, hoping that the League would take firm action to control Italy’s aggressive policies. Britain and France were aware at the time that Hitler had recommenced military conscription in Germany in 1935, and they were eager to gain Italy’s friendship in case Germany and Italy joined in a pact. In April 1935 a meeting was held between Britain, France and Italy at Stresa. The two western powers, Britain and France, hoped that Italy would be willing to join what was known as the Stresa Front. Because of this neither MacDonald nor Sir John Simon, Britain’s representatives, referred to Mussolini’s policy towards Abyssinia.

Ramsay MacDonald resigned because of ill health in 1935, and Stanley Baldwin became Prime Minister and Sir Samuel Hoare Foreign Secretary. In September 1935 Sir Samuel Hoare said in a speech in Geneva that Britain supported the League of Nations and the principle of collective security.

“The collective maintenance of the Covenant in its entirety and particularly for steady collective resistance to all acts of unprovoked agression.” In October 1935, Mussolini attacked Abyssinia. After Abyssinia appealed to the League, it was decided to use economic sanctions against Italy. Again the sanctions were a failure and had no effect on Italy.

The impression was given that the British government supported action through the League and this was welcomed in Britain.

During the 1935 election Stanley Baldwin and the National Government appealed for the support of the electorate by referring to the Government’s success in the economic field and the fact that the Government supported the League. It was announced that the League played an important role in the Government’s foreign policy, and Baldwin said, in referring to the League, “that it would continue as before to be a vital element of British foreign policy”.

At the same time he gave a promise that the Government would do its best to strengthen the League and make it more effective. He also said that Britain was going to begin a certain amount of re-armament, but that he strongly believed in the principle of disarmament and control of the military growth of the major powers. These policies appealed to the electorate and the National Government won 432 seats compared with 180 for the opposition parties.

Therefore, publicly, the Government supported the League, but L. S. Amery in his book, ‘My Political Life’, shows that the main leaders of the National Government were very unwilling to support the League. The following extract is an account of a conversation L. S. Amery had with Samuel Hoare and Neville Chamberlain:

“His view, like Sam’s was that we were bound to try out the League of Nations (in which he does not himself believe very much) for political reasons at home, and that there was no question of our going beyond the mildest economic sanctions, such as an embargo on the purchase of Italian goods or the sale of munitions to Italy. . . If things became too serious, the French would run out first and we could show that we had done our best.”

On 10 December 1935 it was announced that Samuel Hoare had met Pierre Laval, the French Prime Minister, in Paris while on his way to Switzerland. It was announced that the two had solved the problem of Abyssinia by transferring large parts of the country to Italy. There was much opposition to this proposal and it was a great disappointment to many in Britain, especially as the Prime Minister had announced before the 1935 election that the government intended to act through the League.

Because of the opposition to the Hoare-Laval plan, the Foreign Secretary had to resign, and Anthony Eden, one of the supporters of the League, became Foreign Secretary in his place

After this the League of Nations was completely worthless and there is no doubt that Ramsay MacDonald and Stanley Baldwin should shoulder much of the blame for its failure.

It cannot be said that Britain alone was responsible for the failure of the League, but as one of its leading members, Britain probably had more responsiiblity than many others. Nevertheless, the responsibility for the failure of the League fell on the shoulders of all the members. In a speech in the House of Commons in November 1936, after Winston Churchill had condemned his foreign policies, Stanley Baldwin said that it was British residents who were responsible for the government’s policy in 1935-36.

During his speech Baldwin said that pacifism was strong in Britain during these years, and he went on to draw the attention of the House of Commons to political events which proved this statement. He said that the National Government candidate had been defeated in the East Fulham by-election in October 1933 because he was in favour of re-armament. Before the by-election the previous representative of the National Government had a majority of 14,521 but the National Government candidate lost his majority as the opposition representative won by 4,840 votes. Baldwin said that it was best for the National Government to talk as little as possible of re-armament in case the electorate turned to the Labour Party, a party which opposed any steps towards re-armament.

In February 1933, members of the Oxford Student Union had supported the motion:

“That this House will in no circumstances fight for its King and Country”.

Actually this decision was not a particularly important one, but it was part of the pacifist feeling which was strong in Britain at the time. Many books were published condemning war, such as “All Quiet on the Western Front” by Erich Maria Remarque, “Goodbye to all That”, by Robert Graves, “Memoirs of a Foxhunting Man” by Siegfried Sassoon and the play “Journey’s End” by R. C. Sherriff. In 1934 the Peace Pledge Union was established and by the end of the year some 80,000 people had signed the Peace Pledge.

During his speech Baldwin said that he had refused to mention re-armament as he was afraid that the elecotrate would turn against the National Government.

“Supposing I had gone to the country and said that Germany was re-arming and said that we must re-arm, does anybody think that this pacific democracy would have rallied to that cry at that moment? I cannot think of anything that would have made the loss of the election from my point of view, more certain.”

After Winston Churchill heard this answer, he took it that Baldwin was talking of what he did during 1935, and so he accused him of putting party interests before the interests of the country. By today many historians accept that Baldwin was describing some imaginary event rather than referring specifically to the 1935 election.

Looking back at the years 1935-39, it is seen that neither party had any definite policy in favour of re-armament. The Labour Party believed that the country should co-operate with other members of the League of Nations to disarm, whereas the Conservative Party was in favour of acting separately from the League and re-arming gradually to make this policy possible.

While the Conservatives said this, they acted differently. At times willing to co-operate wih the League and at other times acting independently.

The main purpose of the National Government’s foreign policy was to try and keep Hitler and Mussolini apart. In David Thompson’s opinion, such a policy was more likely to draw the two together. There is no doubt that the majority of the British people were keen for Britain to remain a member of the League and use economic sanctions to try to control the dictators. During the winter of 1934, the Peace Vote was held (as an opinion poll) and when the results were announced in June 1935, it was seen that some 11 million Britons thought that Britain should continue as a member of the League working to convince other countries to accept disarmament. About 11 million thought that economic sanctions and other peaceful methods should be used to control the dictators, but it was also seen that about 6¾ million people were willing to support the use of armed force to control the dictators.

David Thompson is very critical of Stanley Baldwin’s policies and says in his book, “England in the 20th Century”, that the Government’s policies during the 1935-37 period reflected the country’s feelings in the same period:

“ In its shirking of unpalatable risks, its mental and moral inertia, the national government, fully represented the mass of British opinion in the Baldwin Age.”

It can be proved that this was true because in 1936, when Hitler sent his soldiers to the Rhineland, Birtain did nothing to oppose him.

THE PERIOD OF NEVILLE CHAMBERLAIN 1937-40

After solving the problems of the monarchy, Stanley Baldwin decided to resign. George VI was crowned on 12 May 1937 and Baldwin resigned on 27 May. Chamberlain became Prime Minister with Sir Anthony Eden as Foreign Secretary (until February 1938) and Sir Samuel Hoare as Home Secretary. Before becoming Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain had said that he would abolish the economic sanctions used against Italy because of Mussolini’s policy towards Abyssinia.

Neville Chamberlain belonged to the same generation as MacDonald and Baldwin but was a completely different character and less likeable than the other two. In David Thompson’s opinion,

“(He was) lacking their warmth and generosity of mind; he drew upon larger resources of energy, will-power and process of thought. . . .(but) he was not born to suffer fools gladly”.

During his political career he had been a successful Health Minister from 1924 to 1929 and then between 1931 and 1937 he had been a strong and determined Chancellor. Unfortunately this did not make him a suitable Prime Minster for the problems facing Britain in 1937. He may have had the ability to be a successful Prime Minister under different circumstances, but it was a personal disaster for him to have to be Prime Minister when international issues were more important than domestic issues.

Immediately after he became Prime Minister, Japan went to war against China in July 1937. The Chinese armies could not withstand the Japanese armies and by the end of 1937 Japan had occupied the cities of Nanking and Shanghai. Although the League of Nations condemned Japan, neither Britain nor France nor the United States made any effort to use economic sanctions to punish Japan. By 1938 Japan had ocuppied Canton and Neville Chamberlain decided not to do anything that would draw Britain into the troubles of the far east. He was keen to maintain peace at any price more or less as that was the USA’s policy too. In March 1938 Hitler sent his troops to invade Austria implementing the Anchluss which was forbidden by the Treaty of Versailles. Before sending his troops to invade Austria, Hitler made himself head of the army in case they refused to accept his command to invade the country. The Chancellor of Austria, Anton Schuschnigg, had tried to persuade Hitler not to invade his country. Hitler refused to listen to Schuschnigg’s appeal and on 12 March 1938 he sent his troops over the border and occupied Vienna, the Austrian capital. Neither Britain nor any other European power was willing to do anything to oppose him.

Meanwhile in February 1938, Anthony Eden had resigned as he opposed Neville Chamberlain’s foreign policy and as the Prime Minister refused to accept his advice. Lord Halifax succeeded him as Foreign Secretary, so after the Spring of 1938 appeasement became part of British foreign policy. At the time that meant taking steps to solve international problems through discussion. Indeed, this method was used to solve a problem that had developed between Britain and Ireland.

It’s possible that the success of conciliation in solving the problem between Brtiain and Ireland had shown Chamberlain that it was possible to solve international problems by discussion. Therefore Chamberlain may have thought it would be wise to try to be conciliatory with Hitler to solve the problem of Czechoslovakia.

In March 1938 Neville Chamberlain said that Czechoslovakia’s geographical position made it impossible for Britain to assist it.

“You have only to look at the map to see that nothing that France or we could do could possibly save Czechoslovakia from being over-run by the Germans if they wanted to do it. . . I have therefore abandoned any idea of giving guarantees to Czechoslovakia and the French in connection with her obligation to that country”.

Hitler was not aware of this and he tried to justify the occupation of Czechoslovakia by saying that the Czechoslovakian government had mistreated the Germans in the Sudetenland. In a speech in the House of Commons on 24 March, Neville Chamberlain said that the use of military force to assist Czechoslovakia against Germany would have to be considered if France decided to do so.

Chamberlain was very keen to avoid war if that was possible and so he sent Lord Runciman to the Sudetenland to see if the Germans were being mistreated by the Czechoslovakian government. Runciman did not see anything that would confirm the German arguments, but it was obvious that Hitler was determined to occupy the Sudetenland.

Chamberlain travelled to Germany twice to meet Hitler in Berchtesgaden and Bad Godesberg, trying to ensure conciliation with Hitler and giving parts of Czechoslovakia to him. This was not successful and war in Europe became more likely. War was avoided when there was a proposal from Mussolini to hold a conference in Munich. On 29 September 1938 Chamberlain went there to meet Hitler, Mussolini and Daladier, the Prime Minister of France. There was nobody there to represent Czechoslovakia or Russia, and the four came to the decision to hand over the Sudetenland to Germany. Chamberlain returned to Britain and was given a hero’s welcome as he had secured peace in Europe He showed a piece of paper to the public signed by himself and Hitler promising that the two countries would not go to war against each other. At the time Chamberlain was a hero not only in Britain but also in the United States. One newspaper in Norway thought that Chamberlain deserved the Nobel peace prize. The New York Daily News wrote: “In Chamberlain’s actions in the last couple of weeks there is something Christ-like. . . Chamberlain showed more of the spirit of the founder of Christianity than any English speaking politician we can remember since Abraham Lincoln”.

Very few MPs opposed the Munich Settlement and only one member of the government, Duff Cooper the War Secretary between 1935 and 1937, was willing to resign because of his opposiiton to the scheme.

In 1938 Germany spent £1,710 million on its armed forces, 25% of the country’s national income. There is little doubt that war was close in 1938, and that the Czechoslovakian government opposed the Munich agreement and was therefore willing to fight. France had called on 600,000 reserve soldiers to join the army. Talks were held between the military leaders of Britain and France. It was clear that Chamberlain was very keen to avoid war at the time, as he said before going to Munich:

“How horrible, fantastic, incredible it is that we should be digging trenches and trying on gas masks here because of a quarrel in a far away country between people of whom we know nothing”.

As a result of the Munich Agreement Hitler had given a promise that the Sudetenland was the last territory he was going to invade, but within six months he had invaded Bohemia and Moravia. After Munich Britain had given a subsidy of £30 million to Czechoslovakia, and as Hitler occupied these territories he took that money too. After this Neville Chamberlain came to the decision to oppose Hitler, realising that no notice could be taken of Hitler’s promises.

Britain agreed to defend Romania and Poland and war in Europe came closer. However Chamberlain was still keen to avoid war, but by September 1939 when Hitler sent his troops to invade Poland, war was inevitable. Public opinion regarding war had changed during the 1930s, and by 1939, many more were willing to listen to Winston Churchill’s arguments. Britain joined the War on 3 September 1939 and Chamberlain remained as Prime Minister until May 1940 when Churchill was appointed in his place.

Hitler had broken his promises and by September 1939, nobody was willing to listen to him. Chamberlain was aware that Hitler had deceived him and so in 1940 when the vote went against him in the House of Commons he was a sad man who had failed to maintain peace in Europe amd had lost Parliament’s support. In the opinion of most historians, Chamberlain had made a mistake in his policy of appeasing Hitler in trying to treat Hitler and Mussolini as ordinary politicians and that he had been deceived by them every time.

However, it must be agreed that Britain had had an opportunity to re-arm during his time as Prime Minister and according to his defenders this was the purpose of his policy of appeasement. This argument is not very strong because Chamberlain had been Chancellor of the Exchequer before becoming Prime Minister and he had refused to spend on re-armament. At one time Baldwin proposed that Britain should borrow money in order to re-arm but Chamberlain refused to consider the idea.

HOW READY WAS BRITAIN TO FACE HITLER IN 1939?

Britain started to re-arm from about 1935 onwards, when the government announced its intention to strengthen the RAF and the Navy. It intended to re-establish Britain’s naval strength and create an air force that was as strong as the German Luftwaffe. When Winston Churchill became head of the navy in 1939, he saw that the British navy was much stronger than the German navy. Unfortunately the governments of the period 1935- 39 had ignored the army, taking it for granted that the army’s purpose was to defend the country rather than intervene in international affairs.

In 1938 Germany spent £1,710 million on its armed forces, 25% of the country’s national income. At the same time Britain was spending £35 million a year, 7% of the national income, France was spending less than Britain. After Munich Britain started to pay more attention to re-armament and in the year 1939-40 it spent £580 million on arms and for the first time the country’s economy was channelled towards military preparations. In 1938, 2,827 planes were built in Britain and 7,940 were built in 1939. At the same time arrangements were made under the leadership of Sir John Anderson to protect the public from the effects of war. Gas masks were distributed and arrangements made to move children and people from the cities On the other hand Germany was not as strong as the impression it gave. Through the Munich agreement, however, it had been able to occupy many important industrial centres in Czechoslovakia including the factories of the Skoda company which produced lorries, tanks and so on. It had also managed to gain ground without any armed force and had managed to make the Czechoslovakian army totally powerless.

The Labour Party had turned its back on disarmament in June 1937, though there were still some pacifists left in the party’s ranks officially. After the Munich Agreement more and more of the Labour Party came to accept that there had to be re-armament as they could not have any faith in Hitler’s promises. It is seen therefore that the most pacific element in Britain was accepting that re-armament was a matter of necessity as it could foresee war against Hitler. While most people were coming to accept that war was more or less inevitable, Chamberlain was still dreaming of peace. He said on 10 March 1939, five days before Germany invaded the remainder of Czechoslovakia, that he could foresee a period of peace in Europe.

The remainder of Czechoslovakia was invaded by Germany in March 1939 and war in Europe became more or less inevitable. After this Chamberlain realised that Britain had to be ready to face European dictators, and while he had previously been very unwilling to promise military support to any of the other European powers, he began to promise support to all after this including Poland, Greece, Romania and Turkey.

Hitler sent his troops to invade Poland on 1 September 1939, hoping that Britain and the western powers would be willing to appease him again. That did not happen and on 3 September 1939 Chamberlain announced that Britain was going to war against Germany.

Before this, on 23 August 1939, Britain and the other Western countries were surprised when it was announced that Germany and Russia had agreed what was called a non- aggression treaty. This was not a military treaty between the two countries, but both countries agreed not to go to war against each other. It was later discovered that there was a secret clause in this treaty and that the two countries had divided large parts of eastern Europe into spheres of influence. Germany was to get western Poland and Lithuania, while Russia was to occupy eastern Poland, Finland, Estonia and Latvia.

David Thompson’s view is that this Treaty was similar to the Munich agreement for Russia. Russia had signed the treaty in order to gain time to prepare for a clash with Germany sometime in the future. Stalin was fiercely criticised in the West for signing this treaty, particularly considering that Communist Rusia was the natural enemy of Nazi Germany. By 17 September Germany had occupied western Poland, and Russia had occupied the east, believing that Germany would give its whole attention to the west from now on.

When the war began Neville Chamberlain led a war cabinet of nine members; he had appointed Winston Churchill to be responsible for the navy and Anthony Eden as Secretary of State for War. These were wise changes, but the country and Parliament had lost faith in Chamberlain, associating him with the disaster of Munich. The Labour Party was not prepared to serve in a government under Chamberlain’s leadership and after a debate and vote in the House of Commons on 10 May 1940, Chamberlain resigned and Winston Churchill became Prime Minister.

Chamberlain has much responsibilty for Britain’s lack of preparation for this war, but as Ernest Bevin said in 1941, “the whole country was responsible for the state of Britain in 1939”.

“If anyone asks me who was responsible for the British policy leading up to the war, I will, as a Labour man myself make a confession and say “All of us”. We refused absolutely to face facts . . . but what is the use of blaming anybody”.