Peripheral Nerve Stimulation in Regional Anesthesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7,074,961 B2 Wang Et Al

US007074961B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7,074,961 B2 Wang et al. (45) Date of Patent: Jul. 11, 2006 (54) ANTIDEPRESSANTS AND THEIR 6.211,171 B1 4/2001 Sawynok et al. ANALOGUES AS LONG-ACTING LOCAL 6,545,057 B1 4/2003 Wang et al. ANESTHETCS AND ANALGESCS 2001/0036943 A1 11/2001 Coe et al. (75) Inventors: Ging Kuo Wang, Westwood, MA (US); FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS Peter Gerner, Weston, MA (US); Donald K. Verrecchia, Winchester, MA CH 534124 A 2, 1973 (US) WO WO95/17903 A1 7, 1995 WO WO95/1818.6 A1 7, 1995 (73) Assignee: The Brigham and Women's Hospital, WO WO 99.59.598 A1 11, 1999 Inc., Boston, MA (US) WO WO O2/060870 A2 8, 2002 (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this OTHER PUBLICATIONS patent is extended or adjusted under 35 U.S.C. 154(b) by 451 days. Luo et al., Xenobiotica, vol. 25, No. 3, pp. 291-301, 1995.* (21) Appl. No.: 10/117,708 Ehlert et al., The Interaction of Amitriptyline, Doxepin, Imipramine and Their N-Methyl Quaternary Ammonium (22) Filed: Apr. 4, 2002 Derivatives with Subtypes of Muscarinic Receptors in Brain (65) Prior Publication Data and Heart, The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, Apr. 1990, vol. 253, No. 1, pp. 13–19. US 2003/00968.05 A1 May 22, 2003 Gerner, P., et al., Anesthesiology (2002) 96:1435–42. Related U.S. Application Dat e pplication Uata Khan, M.A., et al., Anesthesiology (2002) 96:109–16. (63) stripps'965,138, filed on Sep. -

Femoral and Sciatic Nerve Blocks for Total Knee Replacement in an Obese Patient with a Previous History of Failed Endotracheal Intubation −A Case Report−

Anesth Pain Med 2011; 6: 270~274 ■Case Report■ Femoral and sciatic nerve blocks for total knee replacement in an obese patient with a previous history of failed endotracheal intubation −A case report− Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, School of Medicine, Catholic University of Daegu, Daegu, Korea Jong Hae Kim, Woon Seok Roh, Jin Yong Jung, Seok Young Song, Jung Eun Kim, and Baek Jin Kim Peripheral nerve block has frequently been used as an alternative are situations in which spinal or epidural anesthesia cannot be to epidural analgesia for postoperative pain control in patients conducted, such as coagulation disturbances, sepsis, local undergoing total knee replacement. However, there are few reports infection, immune deficiency, severe spinal deformity, severe demonstrating that the combination of femoral and sciatic nerve blocks (FSNBs) can provide adequate analgesia and muscle decompensated hypovolemia and shock. Moreover, factors relaxation during total knee replacement. We experienced a case associated with technically difficult neuraxial blocks influence of successful FSNBs for a total knee replacement in a 66 year-old the anesthesiologist’s decision to perform the procedure [1]. In female patient who had a previous cancelled surgery due to a failed tracheal intubation followed by a difficult mask ventilation for 50 these cases, peripheral nerve block can provide a good solution minutes, 3 days before these blocks. FSNBs were performed with for operations on a lower extremity. The combination of 50 ml of 1.5% mepivacaine because she had conditions precluding femoral and sciatic nerve blocks (FSNBs) has frequently been neuraxial blocks including a long distance from the skin to the used for postoperative pain control after total knee replacement epidural space related to a high body mass index and nonpalpable lumbar spinous processes. -

VHA/Dod CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE for the MANAGEMENT of POSTOPERATIVE PAIN

VHA/DoD CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF POSTOPERATIVE PAIN Veterans Health Administration Department of Defense Prepared by: THE MANAGEMENT OF POSTOPERATIVE PAIN Working Group with support from: The Office of Performance and Quality, VHA, Washington, DC & Quality Management Directorate, United States Army MEDCOM VERSION 1.2 JULY 2001/ UPDATE MAY 2002 VHA/DOD CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF POSTOPERATIVE PAIN TABLE OF CONTENTS Version 1.2 Version 1.2 VHA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Postoperative Pain TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION A. ALGORITHM & ANNOTATIONS • Preoperative Pain Management.....................................................................................................1 • Postoperative Pain Management ...................................................................................................2 B. PAIN ASSESSMENT C. SITE-SPECIFIC PAIN MANAGEMENT • Summary Table: Site-Specific Pain Management Interventions ................................................1 • Head and Neck Surgery..................................................................................................................3 - Ophthalmic Surgery - Craniotomies Surgery - Radical Neck Surgery - Oral-maxillofacial • Thorax (Non-cardiac) Surgery.......................................................................................................9 - Thoracotomy - Mastectomy - Thoracoscopy • Thorax (Cardiac) Surgery............................................................................................................16 -

FDA Briefing, Joint Meeting of Anesthetic and Analgesic Drug

1 FDA Briefing Document Joint Meeting of Anesthetic and Analgesic Drug Products Advisory Committee and Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee January 15, 2020 (AM Session) 2 DISCLAIMER STATEMENT The attached package contains background information prepared by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the panel members of the advisory committee. The FDA background package often contains assessments and/or conclusions and recommendations written by individual FDA reviewers. Such conclusions and recommendations do not necessarily represent the final position of the individual reviewers, nor do they necessarily represent the final position of the Review Division or Office. The new drug application (NDA) 213426 for tramadol 44mg and celecoxib 56mg tablet, which contains a fixed dose combination of an opioid and an NSAID for the management of acute pain in adults that is severe enough to require an opioid analgesic and for which alternative treatments are inadequate, has been brought to this Advisory Committee in order to gain the Committee’s insights and opinions. The background package may not include all issues relevant to the final regulatory recommendation and instead is intended to focus on issues identified by the Agency for discussion by the advisory committee. The FDA will not issue a final determination on the issues at hand until input from the advisory committee process has been considered and all reviews have been finalized. The final determination may be affected by issues not discussed at the advisory committee meeting. 3 FOOD AND DRUG ADMINISTRATION Center for Drug Evaluation and Research Joint Meeting of the Anesthetic and Analgesic Drug Products Advisory Committee and Drug Safety & Risk Management Advisory Committee January 15, 2020 Table of Contents 1 Division Memorandum ....................................................................................................... -

Running Head: ANESTHETIC MANAGEMENT in ERAS PROTOCOLS 1

Running head: ANESTHETIC MANAGEMENT IN ERAS PROTOCOLS 1 ANESTHETIC MANAGEMENT IN ERAS PROTOCOLS FOR TOTAL KNEE AND TOTAL HIP ARTHROPLASTY: AN INTEGRATIVE REVIEW Laura Oseka, BSN, RN Bryan College of Health Sciences ANESTHETIC MANAGEMENT IN ERAS PROTOCOLS 2 Abstract Aims and objectives: The aim of this integrative review is to provide current, evidence-based anesthetic and analgesic recommendations for inclusion in an enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol for patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty (TKA) or total hip arthroplasty (THA). Methods: Articles published between 2006 and December 2016 were critically appraised for validity, reliability, and rigor of study. Results: The administration of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), acetaminophen, gabapentinoids, and steroids result in shorter hospital length of stay (LOS) and decreased postoperative pain and opioid consumption. A spinal anesthetic block provides benefits over general anesthesia, such as decreased 30-day mortality rates, hospital LOS, blood loss, and complications in the hospital. The use of peripheral nerve blocks result in lower pain scores, decreased opioid consumption, fewer complications, and shorter hospital LOS. Conclusion: Perioperative anesthetic management in ERAS protocols for TKA and THA patients should include the administration of acetaminophen, NSAIDs, gabapentinoids, and steroids. Preferred intraoperative anesthetic management in ERAS protocols should consist of spinal anesthesia with light sedation. Postoperative pain should be -

3Rd International Congress on Ambulatory Surgery April 25–28, 1999

Ambulatory Surgery 7 (1999) S1–S108 Abstracts 3rd International Congress on Ambulatory Surgery April 25–28, 1999 suitable and consistent information about the disease, its treatment Organization and Management and possible consequences both of the disease and of its treatment. Lack of information can make the contract null and void causing a physician to act against the law. For the consent to be valid it has to Severity of symptoms following day case cystoscopy be given by a Subject in full possession of his/her faculties or aged to be as such. The surgeon’s obligation so established in the contract is M Cripps the obligation of means or diligence in his/her performance and not Lecturer Practitioner, Day Surgery Unit, Salisbury District Hospital, an obligation to results. A surgeon therefore acts within the limits of Wiltshire, England a behaviour obligation and not of an obligation to results. Neverthe- less this is an apparent distinction, as a fact, considered as a mean in INTRODUCTION: This is the result of a collaborative study under- respect of a subsequent aim, will be a result when assessed as such, taken by six Day Surgery Units around South West England looking and as the final stage of a limited sequence of facts. at the morbidity following day case cystoscopy. Critical management factors (CMF) in an ambulatory surgery center METHODS: The study investigated, through patient questionnaire, the patients’ experience in the first 48 hours post surgery of pain, RC Williams sickness, presence of haematuria, burning on micturition, frequency of micturition and contacts with health care professionals. -

Anesthetic Requirements Measured by Bilateral Bispectral Analysis and Femoral Blockade in Total Knee Arthroplasty

Rev Bras Anestesiol. 2017;67(5):472---479 REVISTA BRASILEIRA DE Publicação Oficial da Sociedade Brasileira de Anestesiologia ANESTESIOLOGIA www.sba.com.br SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE Anesthetic requirements measured by bilateral bispectral analysis and femoral blockade in total knee arthroplasty ∗ Maylin Koo , Javier Bocos, Antoni Sabaté, Vinyet López, Carmina Ribes Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge, Servicio de Anestesia y Medicina Intensiva, Barcelona, Spain Received 14 January 2016; accepted 20 July 2016 Available online 28 August 2016 KEYWORDS Abstract Nerve block; Background and objectives: A continuous peripheral nerve blockade has proved benefits on Pain management; reducing postoperative morphine consumption; the combination of a femoral blockade and Bispectral index general anesthesia on reducing intraoperative anesthetic requirements has not been studied. monitor; The objective of this study was to determine the relevance of timing in the performance of Levopubicaine femoral block to intraoperative anesthetic requirements during general anesthesia for total hydrochloride; knee arthroplasty. Knee arthroplasty Methods: A single-center, prospective cohort study on patients scheduled for total knee arthro- plasty, were sequentially allocated to receive 20 mL of 2% mepivacaine throughout a femoral catheter, prior to anesthesia induction (Preoperative) or when skin closure started (Postopera- tive). An algorithm based on bispectral values guided intraoperative anesthetic management. Postoperative analgesia was done with an elastomeric pump of levobupivacaine 0.125% con- nected to the femoral catheter and complemented with morphine patient control analgesia for 48 hours. The Kruskall Wallis and the chi-square tests were used to compare variables. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Results: There were 94 patients, 47 preoperative and 47 postoperative. -

Treatment for Acute Pain: an Evidence Map Technical Brief Number 33

Technical Brief Number 33 R Treatment for Acute Pain: An Evidence Map Technical Brief Number 33 Treatment for Acute Pain: An Evidence Map Prepared for: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 5600 Fishers Lane Rockville, MD 20857 www.ahrq.gov Contract No. 290-2015-0000-81 Prepared by: Minnesota Evidence-based Practice Center Minneapolis, MN Investigators: Michelle Brasure, Ph.D., M.S.P.H., M.L.I.S. Victoria A. Nelson, M.Sc. Shellina Scheiner, PharmD, B.C.G.P. Mary L. Forte, Ph.D., D.C. Mary Butler, Ph.D., M.B.A. Sanket Nagarkar, D.D.S., M.P.H. Jayati Saha, Ph.D. Timothy J. Wilt, M.D., M.P.H. AHRQ Publication No. 19(20)-EHC022-EF October 2019 Key Messages Purpose of review The purpose of this evidence map is to provide a high-level overview of the current guidelines and systematic reviews on pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatments for acute pain. We map the evidence for several acute pain conditions including postoperative pain, dental pain, neck pain, back pain, renal colic, acute migraine, and sickle cell crisis. Improved understanding of the interventions studied for each of these acute pain conditions will provide insight on which topics are ready for comprehensive comparative effectiveness review. Key messages • Few systematic reviews provide a comprehensive rigorous assessment of all potential interventions, including nondrug interventions, to treat pain attributable to each acute pain condition. Acute pain conditions that may need a comprehensive systematic review or overview of systematic reviews include postoperative postdischarge pain, acute back pain, acute neck pain, renal colic, and acute migraine. -

Ultrasound-Guided Popliteal Nerve Block with Short-Acting Lidocaine in the Surgical Treatment of Ingrown Toenails

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Ultrasound-Guided Popliteal Nerve Block with Short-Acting Lidocaine in the Surgical Treatment of Ingrown Toenails Beom Suk Kim 1,2 , Kyungho Kim 3,4, Jonathan Day 5,6, Jesse Seilern Und Aspang 5,7 and Jaeyoung Kim 3,5,* 1 Uijeongbu Eulji Medical Center, Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Eulji University, Daejeon 11759, Korea; [email protected] 2 Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Korea University College of Medicine, Seoul 02841, Korea 3 Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Armed Forces Daejeon Hospital, Daejeon 34059, Korea; [email protected] 4 Samsung Medical Center, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Seoul 06351, Korea 5 Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, NY 10021, USA; [email protected] (J.D.); [email protected] (J.S.U.A.) 6 School of Medicine, Georgetown University, Washington, DC 20007, USA 7 Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA 30322, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Background: Digital nerve block (DB) is a commonly utilized anesthetic procedure in ingrown toenail surgery. However, severe procedure-related pain has been reported. Although the popliteal sciatic nerve block (PB) is widely accepted in foot and ankle surgery, its use in ingrown toenail surgery has not been reported. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the safety and Citation: Kim, B.S.; Kim, K.; Day, J.; effectiveness of PB in the surgical treatment of ingrown toenails. Methods: One-hundred-ten patients Seilern Und Aspang, J.; Kim, J. surgically treated for an ingrown toenail were enrolled. Sixty-six patients underwent DB, and 44 un- Ultrasound-Guided Popliteal Nerve derwent PB. -

Continuous Sciatic Nerve Block Anesthesia (

BOEZAART AP © 2006 THE JOURNAL OF THE NEW YORK SCHOOL OF REGIONAL CONTINUOUS SCIATIC NERVE BLOCK ANESTHESIA (WWW.NYSORA.COM) CONTINUOUS SCIATIC NERVE BLOCK BY ANDRÉ P BOEZAART MD, PHD Author Affiliation: Department of Anesthesia, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA INDICATIONS Due to the intricacy of the nerve supply of the joints of the lower extremity, sciatic nerve block on its own is almost never adequate as sole anesthetic for lower limb joint surgery. It is almost always necessary to block of the other peripheral nerves to the lower extremity as well. Sciatic nerve block is therefore usually performed in conjunction with femoral nerve block, or at least saphenous branch of the femoral nerve block at the level of the knee or ankle. The sensory distribution of the sciatic nerve supply is outlined in figure 1. “Single shot” sciatic nerve blocks are numerous because the sciatic nerve has a long course in the upper leg. Numerous “sciatic nerve blocks” have been described and most carry the name of some or other author. This communication will describe the subgluteal approach to the sciatic nerve, since it is the belief of the current author that this is the most appropriate approach for continuous sciatic nerve block. Other approaches have been described and are being used successfully, but we feel that the catheter for continuous sciatic blocks, as for all continuous nerve blocks, should be where surgical tourniquets are usually not placed and tourniquets for lower leg surgery is usually applied in the mid-femoral area. Figure 1a. Somatic neurotomal distribution of the lower extremity. -

Clinicians United to Resolve the Epidemic (CO's CURE)

Colorado’s Opioid Solution: Clinicians United to Resolve the Epidemic (CO’s CURE) The Colorado Chapter of the American College of Emergency Physicians 2020 Opioid Prescribing and Treatment Guidelines Developed by Colorado ACEP in partnership with Colorado Hospital Association, Colorado Medical Society and Colorado Consortium for Prescription Drug Abuse Prevention CO’s CURE is a proud collaboration of the following sponsoring and participating societies and organizations. The CO’s CURE initiative’s leadership thanks each for its contributions, expertise and commitment to ending the opioid epidemic together. SPONSORING ORGANIZATIONS COLORADO EST. 1871 MEDICAL SOCIETY PARTICIPATING ORGANIZATIONS FUNDED BY Colorado Department of Human Services, Office of Behavioral Health SPECIAL THANKS TO Support for Hospital Opioid Use Treatment (Project SHOUT) and BridgetoTreatment.org Dedicated to the clinicians across Colorado and the patients for whom they care Page 1 Contributors Editor-in-Chief Donald E. Stader III, MD, FACEP Copy Editors Emergency Physician Editors Paula Benson Dylan Luyten, MD, FACEP Julie Denning Ashley Morse, MD Rachel Donihoo Erik Verzmeniks, MD, FACE Steve Young, MD Task Force Chair Erik Verzmeniks, MD, FACEP Associate Editors Elizabeth Esty, MD Task Force Members, Volunteers and Other Contributors John Spartz Travis Barlock, MD Kevin Boehnke, PhD Section Editors Jon Clapp, MD Robert Valuck, PhD, RPh, FNAP Will Dewispelaere Introduction and The Opioid Epidemic in Colorado Kenneth Finn, MD Erik Verzemnieks, MD, FACEP Chris Johnston, MD Limiting Opioid Use in the Emergency Department Kevin Kuachar, PharmD Rachael Duncan, PharmD, BCCCP Emily Lampe, MD Charleen Gnisci Melton, PharmD, BCCCP Judy Lane, MD Donald E. Stader III, MD, FACEP Julia Luyten Alternatives to Opioids for the Treatment of Pain Rachael Rzasa Lynn, MD Martin Krsak, MD Jeffrey Wagner, MD Donald E. -

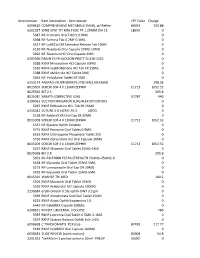

Item Master CPT Code Charge 6090610 COMPREHENSIVE

Item Number Item Description - Item Master CPT Code Charge 6090610 COMPREHENSIVE METABOLIC PANEL w/ Reflex- 80053 103.88 6202327 WIRE SYNT TIT KIRS TROC PT 1.25MM DIA 15 L8699 0 5387 NF-Premarin Oral Tablet 0.9MG 0 5398 NF-Falmina Tab 0.2MF-0.1MG 0 5517 NF-LaMICtal XR Extended Release Tab 100M 0 6130 NF-Nuedexta Oral Capsule 20MG-10MG 0 5992 NF-Terazosin HCl Oral Capsule 2MG 0 6203390 DRAIN 19 FR JACKSON-PRATT SU130-1325 0 5288 RXNF Minocycline HCl Capsule 50MG 0 5310 RXNF oxyMORphone HCl Tab ER 15MG 0 5388 RXNF aMILoride HCl Tablet 5MG 0 5564 NF- Felodipine Tablet ER 5MG 0 6213174 ANSPACH BURR 6MM FLUTED BALL MIA166B 298.36 8015007 SCREW SOF 4 X 11MM ZEPHIR C1713 1052.52 8025916 BIT 2.3 205.8 8026081 SA6AT5 CORRECTIVE LENS V2787 440 6200062 SUCTION IRRIGATOR SURGIFLEX 007200-903 0 5287 RXNF PARoxetine HCL Tab ER 25MG 0 6215042 SUTURE 3-0 VICRYL PS-2 J497G 0 6138 NF-Adderall XR Oral Cap ER 30MG 0 8015008 SCREW SOF 4 X 13MM ZEPHIR C1713 1052.52 5337 NF-Systane Ophth Solution 0 3774 RXNF Premarin Oral Tablet 0.9MG 0 6162 RXNF Chloroquine Phosphate Tablet 250 0 5756 RXNF Ziprasidone HCl Oral Capsule 20MG 0 8015009 SCREW SOF 4 X 15MM ZEPHIR C1713 1052.52 5427 RXNF Glyxambi Oral Tablet 25MG-5MG 0 8025918 BIT 2.5 205.8 5959 NF-EXCEDRIN EXTRA STRENGTH 250MG-250MG-6 0 5428 NF-Glyxambi Oral Tablet 25MG-5MG 0 5273 NF-Lansoprazole Oral Cap DR 30MG 0 5429 NF-Glyxambi Oral Tablet 25MG-5MG 0 8015391 WASHER TRI MED 180.2 5504 RXNF Movantik Oral Tablet 25MG 0 5336 RXNF Acebutolol HCl Capsule 200MG 0 2290384 erythromycin 0.5% ophth OINT 3.5 gm 0 5399 RXNF