A Descriptive Cultural Study of Children's Play

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thesis Draft

! ! ! ! ! The Mobile Citizen: Canada’s Treatment of Mobility in Immigration, Citizenship, and Foreign Policy ! Alex M. Johnston ! ! Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Political Science ! ! School of Political Studies Faculty of Social Science University of Ottawa ! ! © Alex M. Johnston, Ottawa, Canada, 2017. The Mobile Citizen ii Abstract ! Mobility, as the ability among newcomers and citizens to move temporarily and circularly across international borders and between states, has become a pervasive norm for a significant portion of Canada’s population. Despite its pervasive nature and the growing public interest, however, current research has been limited in how Canadian policies are reacting to the ability of citizens and newcomers to move. This thesis seeks to fill that gap by analyzing Canada’s treatment of mobility within and across policies of immigration, citizenship and foreign affairs. An analytical mobility framework is developed to incorporate interdisciplinary work on human migration and these policy domains. Using this framework, an examination of policy developments in each domain in the last decade reveals that they diverge in isolation and from a whole-of-government perspective around the treatment of mobility. In some instances policy accommodates or even embraces mobility, and in others it restricts it. The Mobile Citizen iii Table of Contents Abstract i Table of Contents and List of Table and Figures ii Introduction -

Not Quite White: Lebanese and the White Australia Policy, 1880 to 1947 by Anne Monsour (Review)

Not Quite White: Lebanese and the White Australia Policy, 1880 to 1947 by Anne Monsour (review) Catriona Elder Mashriq & Mahjar: Journal of Middle East and North African Migration Studies, Volume 1, Number 2, 2013, (Review) Published by Moise A. Khayrallah Center for Lebanese Diaspora Studies For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/779776/summary [ Access provided at 28 Sep 2021 06:18 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] Mashriq & Mahjar 1, no. 2 (2013), 125-129 ISSN 2169-4435 ANNE MONSOUR, Not Quite White: Lebanese and the White Australia Policy, 1880 to 1947 (Brisbane: Post Pressed, 2010). Pp. 216. $45.65 paper. REVIEWED BY CATRIONA ELDER, Department of Sociology and Social Policy, University of Sydney, email: [email protected] After receiving Anne Monsour’s book Not Quite White to review, I put it on my bookshelf at work to read a little further down the track. Taking it home one day a few weeks later, I discovered I mistakenly had picked up the wrong book. I also had on the shelf a copy of a book by Matt Wray with the same main title, but the sub-title “white trash and the boundaries of whiteness.”1 Since I was not going to get to read Monsour’s book that evening, I flicked through Wray’s monograph instead. Though exploring a different topic – the emergence of the pejorative term “white trash” to describe a segment of the American population – there were sections of this book, that I discovered later, resonated with Monsour’s work. In setting out the theoretical framework for his argument Wary returns to the eugenics and scientific material of the late nineteenth century, where the “classifying impulse” was on show. -

The Land of Glory and Beauties

IRAN The Land of Glory and Beauties Iranian Cultural Heritage, Handicrafts and Tourism Organization www.tourismiran.ir Iran is the land of four seasons, history and culture, souvenir and authenticity. This is not a tourism slogan, this is the reality inferred from the experience of visitors who have been impressed by Iran’s beauties and amazing attractions. Antiquity and richness of its culture and civilization, the variety of natural and geographical attractions, four - season climate, diverse cultural sites in addition to different tribes with different and fascinating traditions and customs have made Iran as a treasury of tangible and intangible heritage. Different climates can be found simultaneously in Iran. Some cities have summer weather in winter, or have spring or autumn weather; at the same time in summer you might find some regions covered with snow, icicles or experiencing rain and breeze of spring. Iran is the land of history and culture, not only because of its Pasargad and Persepolis, Chogha Zanbil, Naqsh-e Jahan Square, Yazd and Shiraz, Khuzestan and Isfahan, and its tangible heritage inscribed in the UNESCO World Heritage List; indeed its millennial civilization and thousands historical and archeological monuments and sites demonstrate variety and value of religious and spiritual heritage, rituals, intact traditions of this country as a sign of authenticity and splendor. Today we have inherited the knowledge and science from scientists, scholars and elites such as Hafez, Saadi Shirazi, Omar Khayyam, Ibn Khaldun, Farabi, IRAN The Land of Glory and Beauties Ibn Sina (Avicenna), Ferdowsi and Jalal ad-Din Muhammad Rumi. Iran is the land of souvenirs with a lot of Bazars and traditional markets. -

Are Muslim Immigrants Really Different

Are Muslim immigrants really different? Experimental Evidence from Lebanon and Australia Maleke Fourati∗ Danielle Hayeky August 12, 2019 Abstract This paper aims to identify the effect of religion on individual cooperative behaviour towards women and the poor by focusing on Muslim immigrants. In particular, it attempts to shed light on whether religion or the social environment of immigration influences the distinct behaviour exhibited by Muslim immigrants in Western destination countries. We test this by conducting a prisoner's dilemma game with the Lebanese population in Australia (destination country) and the Lebanese population in Lebanon (native country). This unique sample allows us to remove the effects of confounds such as economic institutions of country of ancestry, ethnolinguistic groupings and culture. In both countries, we compare Lebanese Muslims to Lebanese Christians to isolate the effect of religion. We find that in Lebanon, Muslims and Christians behave similarly, while in Australia, when compared to Christians, Muslims are more cooperative (i.e., send a higher share of their endowment) towards the poor and especially towards poor females. These results hold even after controlling for altruistic behaviour. We conclude that distinct behaviours displayed by Muslims are not driven by religion but rather migration status. Differing levels of social capital between these two religious groups in Australia seem to explain these findings. JEL Classification: D81, D03, Z12 Keywords: Behavioral Microeconomics, Field Experiment, Religion ∗University of Geneva, [email protected] ySchool of Economics, UNSW Business School, [email protected] 1 1. Introduction In recent decades, the issue of Muslim immigration has been at the forefront of countless political and intellectual debates in the Western World1. -

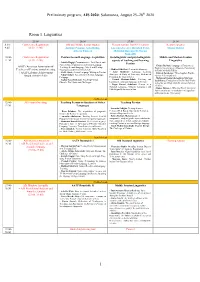

Preliminary Program, AIS 2020: Salamanca, August 25–28Th 2020

Preliminary program, AIS 2020: Salamanca, August 25–28th 2020 Room 1. Linguistics 25.08 26.08 27.08 28.08 8:30- Conference Registration Old and Middle Iranian studies Plenary session: Iran-EU relations Keynote speaker 9:45 (8:30–12:00) Antonio Panaino, Götz König, Luciano Zaccara, Rouzbeh Parsi, Maziar Bahari Alberto Cantera Mehrdad Boroujerdi, Narges Bajaoghli 10:00- Conference Registration Persian Second Language Acquisition Sociolinguistic and psycholinguistic Middle and Modern Iranian 11:30 (8:30–12:00) aspects of teaching and learning Linguistics - Latifeh Hagigi: Communicative, Task-Based, and Persian Content-Based Approaches to Persian Language - Chiara Barbati: Language of Paratexts as AATP (American Association of Teaching: Second Language, Mixed and Heritage Tool for Investigating a Monastic Community - Mahbod Ghaffari: Persian Interlanguage Teachers of Persian) annual meeting Classrooms at the University Level in Early Medieval Turfan - Azita Mokhtari: Language Learning + AATP Lifetime Achievement - Ali R. Abasi: Second Language Writing in Persian - Zohreh Zarshenas: Three Sogdian Words ( Strategies: A Study of University Students of (m and ryżי k .kי rγsי β יי Nahal Akbari: Assessment in Persian Language - Award (10:00–13:00) Persian in the United States Pedagogy - Mahmoud Jaafari-Dehaghi & Maryam - Pouneh Shabani-Jadidi: Teaching and - Asghar Seyed-Ghorab: Teaching Persian Izadi Parsa: Evaluation of the Prefixed Verbs learning the formulaic language in Persian Ghazals: The Merits and Challenges in the Ma’ani Kitab Allah Ta’ala -

Australian Muslim Citizens: Questions of Inclusion and Exclusion, 2006 –2020

Edith Cowan University Research Online ECU Publications Post 2013 2020 Australian Muslim citizens: Questions of inclusion and exclusion, 2006 –2020 Nahid A. Kabir Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ecuworkspost2013 Part of the Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, and the Sociology Commons Kabir, N. A. (2020). Australian Muslim citizens. Australian Journal of Islamic Studies, 5(2), 4-28. https://ajis.com.au/ index.php/ajis/article/view/273 This Journal Article is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ecuworkspost2013/9848 Australian Journal of Islamic Studies https://ajis.com.au ISSN (online): 2207-4414 Centre for Islamic Studies and Civilisation Charles Sturt University CRICOS 00005F Islamic Sciences and Research Academy of Australia Australian Muslim Citizens Questions of Inclusion and Exclusion, 2006–2020 Nahid Kabir To cite this article: Kabir, Nahid. “Australian Muslim Citizens: Questions of Inclusion and Exclusion, 2006–2020.” Australian Journal of Islamic Studies 5, Iss 2 (2020): 4-28. Published online: 28 September 2020 Submit your article to this journal View related and/or other articles in this issue Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://ajis.com.au/index.php/ajis/tncs Australian Journal of Islamic Studies Volume 5, Issue 2, 2020 AUSTRALIAN MUSLIM CITIZENS: QUESTIONS OF INCLUSION AND EXCLUSION, 2006–2020 Nahid Kabir* Abstract: Muslims have a long history in Australia. In 2016, Muslims formed 2.6 per cent of the total Australian population. In this article, I discuss Australian Muslims’ citizenship in two time periods: 2006– 2018 and 2020. -

The Influence of City-Village Distance on the Transformation of Remote Villages in Tehran Region, Iran

The Influence of City-Village Distance on the Transformation of Remote Villages in Tehran Region, Iran Maryam Shafiei University of Queensland In urban scholarship, the “centre-periphery” model has frequently been employed to interpret the explosive growth of cities and their contiguous satellites. However, most such studies illuminate the impact of centre-periphery distances merely in bland physical terms, leaving little room for cultural interpretation. Within this framework, this paper revisits the centre-periphery model to interpret the impact of distance on tangible and intangible structures peculiar to the remote villages surrounding Tehran. City and village in the Tehran region are historically outlined as spatially confined entities, separated by physical distances that pose barriers to their connectivity. Paradoxically, the two have become entirely connected in recent decades, catalysed through modernisation, infrastructural development and policy changes. In fact, distance no longer remains a barrier to physical accessibility. Rather, this distance represents a desire that highlights their cultural and environmental differences realised on the salubrious village periphery, leading to temporary migrations from the city towards peripheral villages with their , edited by Victoria by , edited healthier and more relaxed lifestyle. Meanwhile, the Tehran metropolis itself has been profoundly influenced by Western culture, as well as by ethnic-based cultural patterns brought by rural migrants arriving since the 1950s. Therefore, through the reverse migration of Tehran’s residents to the agrarian periphery, the city’s lifestyle, expertise and culture are gradually supplanting what had once constituted Proceedings of the Society of Architectural village life. This paper argues that such a process has transformed these villages into , Distance Looks Back hybrid entities whereby cumulative economic, architectural and cultural structures 36 are emitted by the centre, imposing tangible and intangible implications on these peripheral communities. -

Lebanese Masculinity in Australia Australian-Grown Or Australian-Misinterpreted

2011 International Conference on Social Science and Humanity IPEDR vol.5 (2011) © (2011) IACSIT Press, Singapore Lebanese Masculinity in Australia Australian-Grown Or Australian-Misinterpreted Victor A, Khachan Department of Humanities and Social Sciences Lebanese American University Byblos, Lebanon [email protected] Abstract—Amidst interpretations of Lebanese masculinity (i.e. Lebanese-Australians male youths’ hierarchy of masculinity hypermasculinity, Lebs Rule, swarming packs of Lebanese), as ‘hypermasculinity/protest masculinity’, justifying the this paper attempts to introduce masculinity in Lebanon in the ‘Lebs Rule’ mythology and its related violence. That is, this framework of Lebanese social identity and its possible links to violence-related hypermasculinity is a means to balance out the Lebanese community in Australia. Investigating the social the ‘humiliation of racism’that is directly associated with identity roots of masculinity in Lebanon may help clarify what the Lebanese youths’ fathers have endured of “lack of whether the ‘phenomenal’ social performance associated with honour and respect in the world of work [which] is the Lebanese community in Australia is Australian-grown or compounded with loss of honour and respect in the family” Australian- misinterpreted. Accordingly, this paper sheds light (p.7) [2]. Accordingly, Lebanese ‘hypermasculinity’ is on the socio-political structure of village identity in Lebanon viewed as an Australian phenomenon and an ultimate and its functional dimension as ‘imagined’ community for Lebanese immigrants, specifically for Australian-Lebanese. determiner of Lebanese-Australians’ ethnic identity [2]. Lebanese-Australians unlike any other Lebanese community Similarly, many researchers reject the association of the term outside Lebanon duplicate the Lebanese social fabric. This ‘gang’ with Lebanese groups and label Lebanese-Australians functionality necessitates a two-fold task. -

DARKNESS and LEBANESE AUSTRALIAN ETHNIC IDENTITY in AUSTRALIAN ENGLISH Josh Clothier

A SOCIOPHONETIC ANALYSIS OF /l/ DARKNESS AND LEBANESE AUSTRALIAN ETHNIC IDENTITY IN AUSTRALIAN ENGLISH Josh Clothier University of Melbourne & ARC Centre of Excellence for the Dynamics of Language [email protected] ABSTRACT tributed [11]; however, while /l/ has also been argued to be dark in all contexts [31] this has not been tested Ethno-cultural varieties of Australian English are ex- empirically to any great extent. pected to grow in the 21st century [10], yet we know Previous acoustic phonetic analysis of Lebanese little about the phonetic detail of the linguistic reper- Australians’ speech shows prosodic differences com- toires of speakers from the many ethno-cultural pared to “mainstream” AusE [12], as well as complex groups in Australia. In Australian English, /l/ has sociophonetic variation in VOT which varies as a been said to be dark in all word positions; however, function of gender, social network, degree of reli- this has not been thoroughly tested to date. This paper gious affiliation, and ethnic identity [8, 9]. compares the acoustic properties of /l/ produced by Anglo-Celtic Australians (N = 20), and Lebanese 1.1. /l/ darkness in English and Arabic Australians (N = 30), who represent the 9th largest ethno-cultural group in Australia. In other varieties of English which exhibit varying de- Results from a wordlist task show that word po- grees of /l/ clearness-darkness, the production of /l/ sition has the strongest effect on /l/ darkness, such by minority-ethnic and bilingual speakers has been that /l/ is darker word-finally than word-initially, as investigated [e.g., 19, 20]. -

Re-Imagining National Struggle

Centre for Middle Eastern Studies Re-imagining national struggle Resistance narratives within the exiled Kurdistan Democratic Party of Iran Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts in Middle Eastern Studies Author: Carl Bradshaw Advisors: Vittorio Felci and Torsten Janson Examiner: Rola El-Husseini Date: June 20, 2019 I am in love with the mountains, hills, and rocks. Even if I freeze today because of hunger and nudity, I will not submit to the settlements of the foreigner as long as I am on this land. I am not afraid of chains nor cords nor sticks nor prison. Cut in pieces until they kill me, I will still say that I am a Kurd. Hemin Mukriyani, Poet Laureate of the Republic of Kurdistan (Natali 2005, 127) ii Abstract In 2016 the Kurdistan Democratic Party of Iran (KDPI) decided to modify its resistance strategy towards the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI). This study analyses political imaginations within the displaced KDPI community in Iraqi Kurdistan through a social constructivist paradigm and the methods of observations and interviews. Findings highlight “insider views” of resistance and outline how identity processes and memory cultures are pivotal to comprehend resistance narratives within the KDPI community. The study further suggests that identity construction is manufactured by broader shared values rather than narrow ethno-cultural allegiance, while being enunciated through nationalist discourse in pursuit of ideational legitimacy. Concerning memory, findings indicate that history is reconstructed to support present political needs. Memories emblematize values of heroism and trauma, constituting a central power resource through which KDPI members express their identity constructions and legitimize resistance. -

Thesis Endfassung Rough999

Angewandte Medienwirtschaft Sport-, Medien- & Eventmanagement Mueller, Timo Does the Arab Film Festival in Sydney support the social acceptance of the Arabic community in Australia? - Bachelorarbeit - Hochschule Mittweida – University of Applied Science (FH) Hemsbach, 2010 1 Angewandte Medienwirtschaft Sport-, Medien- & Eventmanagement Mueller, Timo Does the Arab Film Festival in Sydney support the social acceptance of the Arabic community in Australia? - eingereicht als Bachelorarbeit - Hochschule Mittweida – University of Applied Science (FH) Erstprüfer Prof. Dr. phil. Ludwig Hilmer Zweitprüfer Heinz- Ludwig Nöllenburg 2 Bibliographical Description Mueller, Timo: Does the Arab Film Festival in Sydney support the social acceptance of the Arabic com- munity in Australia? 2010 – 68 pages Hemsbach, Hochschule Mittweida (FH), Fachbereich Medien, Bachelor Thesis Review This Bachelor thesis is focusing on the question of whether the Arab Film Festival in Sydney supports the social acceptance of the Arabic community in Australia. To answer this question, the situation of the Arabic community in Australia is explained and pre- sented in the beginning. This is followed by a closer look at the Muslim community and their part of building Australia’s cultural diversity. Also, the difficult process at integra- tion, which is constrained by the negative image of the Arabic World and portrayed throughout the Western media, is presented. The main focus of this thesis is on how the Arab Film Festival is addressing the prob- lems and struggles Arab Australians have had to face ever since the “War on Terror”, which has especially emerged from the involvement of terrorists of Arabic origin in the attacks on September 11 on the United States of America in 2001. -

Place-Making in National Parks

Denis Byrne, Heather Goodall & Allison Cadzow Place-making in national parks Ways that Australians of Arabic and Vietnamese background perceive and use the parklands along the Georges River, NSW Front cover photographs: © Land and Property Information, Digital Aerial Photography series 2010. © Copyright State of NSW and Office of Environment and Heritage NSW. The Office of Environment and Heritage and the State of NSW are pleased to allow this material to be reproduced for educational or non-commercial purposes in whole or in part, provided the meaning is unchanged and its source, publisher and authorship are acknowledged. Disclaimer: Although every reasonable effort has been made to ensure that this document is correct at the time of publication, the State of NSW, its agencies and employees, disclaim any and all liability to any person in respect of anything or the consequences of anything done or omitted to be done in reliance upon the whole or any part of this document. No representation is made about the accuracy, completeness or suitability of the source material included in this document for any particular purpose. Readers should consult the source material referred to and, where necessary, seek appropriate advice about the suitability of this document for their needs. Published by: Office of Environment and Heritage 59–61 Goulburn Street PO Box A290 Sydney South 1232 Report pollution and environmental incidents Environment Line: 131 555 (NSW only) or [email protected] See also www.environment.nsw.gov.au Phone: (02) 9995