Comparison of Early and Delayed Removal of Dressing Following

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Caring for Yourself After Surgery: Preventing Surgical Site Infections

CARE AT HOME SERIES CARE AT HOME SERIES Caring for Yourself After Surgery Caring for Yourself After Surgery Preventing Surgical Site Infections Preventing Surgical Site Infections Wounds Canada has developed this simple guide that can be used by patients and their care partners when they are looking after a surgical wound. It provides guidance on things to do before and after surgery to help prevent infections and recognize the signs of infections if they do occur. In the past, people stayed in hospital for days or weeks following surgery. In those days, many of the complications that can occur soon after surgery (like infections, heart problems or bleeding) were treated when patients were still recovering in hospital. Today, patients having surgery get home Uninfected, healed surgical incision site. (See page 4 for faster than ever, often even the same day. Surgical uninfected and infected surgical incision sites.) site infections (SSIs) that were once treated in hospital are now being managed by patients at home. The good news is that there are actions you can take before and after your surgery to reduce the chances of developing a serious SSI. What is a surgical site infection? A surgical site infection is a problem where there are too many bacteria or really dangerous, active bacteria in your surgical incision. SSIs cause pain and delay wound healing. In more severe cases, SSIs can spread into the bloodstream (a condition called sepsis), which can lead to tissue loss, organ failure and death. A surgical site infection can be on the surface or deep. How much damage it does depends on how healthy you are as well as how strongly the bacteria affect your tissues. -

Causes of Surgical Wound Dehiscence: a Multicenter Study

J Wound Manag Res 2018 September;14(2):74-79 pISSN 2586-0402 https://doi.org/10.22467/jwmr.2018.00374 eISSN 2586-0410 Journal of Wound Management and Research Causes of Surgical Wound Dehiscence: A Multicenter Study Jeong Jin Chun1, Seok Min Yoon1, Woo Jin Song1, Hyun Gyo Jeong1, Chang Yong Choi2, Syeo Young Wee1 1Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, College of Medicine, Soonchunhyang University, Gumi; 2Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, College of Medicine, Soonchunhyang University, Bucheon, Korea Abstract Surgical wound dehiscence is a postoperative complication involving breakdown of surgical incision site. Despite the in- creased knowledge of wound healing mechanism before and after surgery, wound dehiscence may increase the length of hospital stay, increase patient inconvenience and rates of re-operation. The purpose of this study was to analyze the causes of wound dehiscence in patients undergoing reoperation at 4 hospitals of Soonchunhyang Medical Center. The number of patients in each hospital and those operated previously were compared. In addition, other characteristics of patients were compared in patients who underwent reoperation. In 22 out of 1,026 patients consulted at the Seoul hos- pital, 32 cases out of 1,295 at Bucheon hospital, 14 cases out of 1,687 at Cheonan hospital and 15 cases out of 374 at Gumi hospital, wound revision was performed for wound dehiscence. Patients at the Department of Obstetrics and Gy- necology were the most common and included 33 patients (39.8%). The most common intervention before wound revi- sion was Cesarean section in 14 patients (19.3%). In this study, we retrospectively reviewed patients who underwent wound revision due to wound dehiscence and analyzed the underlying causes of the postoperative complication. -

Risk Factors for Surgical Wound Dehiscence by Hazim Ibrahim DPM 1

! The Northern Ohio Foot and Ankle Journal Official Publication of the NOFA Foundation A Literature Review of Causes and Risk Factors for Surgical Wound Dehiscence by Hazim Ibrahim DPM 1 The Northern Ohio Foot and Ankle Journal 4(26): 1-5 Abstract: Postoperative wound healing plays a significant role in facilitating a patient’s recovery and rehabilitation. Surgical wound dehiscence (SWD) impacts mortality and morbidity rates and significantly contributes to prolonged hospital stays and associated psychosocial stressors on individuals and their families. Most common risk factors associated with SWD include obesity and wound infections, particularly in the case of orthopedic surgery. There is limited reporting of variables associated with SWD across other surgical domains and a lack of risk assessment tools. Furthermore, there was a lack of clarity in the definition of SWD in the literature. This review provides an overview of the available research and provides a basis for more rigorous analysis of factors that contribute to SWD. Key words: Dehiscence, wound infection, obesity This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License. It permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ©The Northern Ohio Foot and Ankle Foundation Journal. (www.nofafoundation.org) 2016. All rights reserved. time. The third week after surgery the durability equals 20% of the initial strength, and after 6-12 Wound dehiscence is one of the most weeks it reaches 70-80% (1). Sutures placed during surgery allow the tissues the necessary time to regain common complications of surgical incision sites. -

Suturing with U-Technique Versus Un

Official Title of the Study: Suturing with U-Technique versus Un- Reapproximated wound Edges during removal of Closed Thoracostomy-tube drain - A single centre Open-label randomized prospective trial (SUTURE TRIAL) NCT NUMBER: Not Yet Assigned DATE OF DOCUMENT: January 16, 2019 1 STUDY SUMMARY Title: Suturing with U-Technique versus Un-Reapproximated wound Edges during removal of Closed Thoracostomy-tube drain - A single centre Open-label randomized prospective trial (SUTURE TRIAL) Background: Closed thoracostomy tube drainage or chest tube insertion is one of the most commonly performed procedures in thoracic surgery. There are several published evidence-based guidelines on safe performance of a chest tube insertion. However, there is absence of prospective controlled trials or systematic reviews indicating the safest technique of closing the wound created at the time of chest tube insertion and that best guarantees good wound and overall outcomes, post-chest tube removal. The use of a horizontal mattress non-absorbable suture or U- suture which is placed at the time of chest tube insertion and used to create a purse-string wound re-approximation at the time of tube removal has been an age-long and time-honored practice in most thoracic surgical settings. It has been established by a recent study that an occlusive adhesive-absorbent dressing can also be safely used to occlude the wound at the time of chest tube removal with good wound and overall outcomes though the study focused on tubes inserted during thoracic surgical operations. -

Corticosteroids and Wound Healing: Clinical Considerations in the Perioperative Period

The American Journal of Surgery (2013) 206, 410-417 Review Corticosteroids and wound healing: clinical considerations in the perioperative period Audrey S. Wang, M.D.a,*, Ehrin J. Armstrong, M.D., M.Sc.b, April W. Armstrong, M.D., M.P.H.a aDepartment of Dermatology, University of California, Davis, 3301 C Street, Suite 1400, Sacramento, CA 95816; bDepartment of Internal Medicine, Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, University of California, Davis, 4860 Y Street, Suite 2820, Sacramento, CA 95817 KEYWORDS: Abstract Corticosteroids; BACKGROUND: Determining whether systemic corticosteroids impair wound healing is a clinically Wound healing; relevant topic that has important management implications. Perioperative METHODS: We reviewed literature on the effects of corticosteroids on wound healing from animal and human studies searching MEDLINE from 1949 to 2011. RESULTS: Some animal studies show a 30% reduction in wound tensile strength with perioperative corticosteroids at 15 to 40 mg/kg/day. The preponderance of human literature found that high-dose cor- ticosteroid administration for ,10 days has no clinically important effect on wound healing. In patients taking chronic corticosteroids for at least 30 days before surgery, their rates of wound complications may be increased 2 to 5 times compared with those not taking corticosteroids. Complication rates may vary depending on dose and duration of steroid use, comorbidities, and types of surgery. CONCLUSIONS: Acute, high-dose systemic corticosteroid use likely has no clinically significant effect on wound healing, whereas chronic systemic steroids may impair wound healing in susceptible individuals. Ó 2013 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. The effects of corticosteroids on wound healing have perioperative corticosteroid administration, namely, dosing, been a topic of great interest among surgeons, internists, and chronicity, and timing relative to surgery. -

Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Infection in a Diabetic Patient with Femorotibial Vascular Bypass Occlusion

ORIGINALACUTE MEDICAL RESEARCH CARE ClinicalClinical Medicine Medicine 2020 2017 Vol 20, Vol No 17, 1: No 98–100 6: 98–8 Surgical wound dehiscence complicated by methicillin- resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection in a diabetic patient with femorotibial vascular bypass occlusion Authors: Enrico M Zardi,A Nunzio Montelione,B Rossella C Vigliotti,C Camilla Chello,D Domenico M Zardi,E Francesco SpinelliF and Francesco StiloG Diabetic patients with critical limb ischaemia may be affected combined with endarterectomy of the superficial femoral artery. A by severe wound and skin ulcer infections. We report a case of month later he underwent the calcaneal skin ulcers debridement. a patient with bilateral femorotibial occlusion and methicillin- The wound specimen for bacterial culture was positive for resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. The patient was Staphylococcus haemolyticus, Corynebacterium aurimucosum treated with femoroperoneal vascular bypass, debridement and Corynebacterium simulans, he was treated with intravenous ABSTRACT of wound dehiscence and targeted antimicrobial therapy for teicoplanin at 400 mg once per day and intravenous meropenem symptom resolution and healing of the wound. at 500 mg every 8 hours. In June and July, he was admitted to our hospital for rest pain and persistence of bilateral calcaneal KEYWORDS: Diabetes, infection, skin ulcer, therapy, vascular bypass ulcers; he was treated with left femorotibial posterior bypass and right femorotibial anterior bypass, using the greater saphenous vein. After an additional -

Preventing Wound Dehiscence: Tension-Relieving and Closure

NOVEMBER 2005 VOL 7.10 Peer Reviewed Editorial Mission Preventing Wound To provide busy practitioners with concise, peer-reviewed recommendations on current treatment standards drawn from Dehiscence: Tension-Relieving published veterinary medical literature. and Closure Options Michael M. Pavletic, DVM, DACVS This publication acknowledges that Director of Surgical Services standards may vary according to individual Angell Animal Medical Center experience and practices or regional Boston, Massachusetts differences. The publisher is not responsible ncisional skin tension is noted by the relative lack of elastic skin bordering the for author errors. surgical site. On digital examination, the skin is taut and shows little or no mobility Reviewed 2015 for significant advances Iwhen pressed. Skin closures under these circumstances have a greater risk of failure, although determining the probability of failure on a clinical basis is inexact. in medicine since the date of original Many skin wounds are routinely sutured under variable degrees of skin tension; a publication. No revisions have been portion of such closures is destined to separate or undergo wound dehiscence. On the made to the original text. lower extremities, closure of skin wounds under tension can result in distal limb edema secondary to circulatory compromise and lymphatic stasis. Without prompt intervention, significant tissue necrosis may occur. Editor-in-Chief The skin of dogs and cats varies both in thickness and elasticity. On the trunk, Douglass K. Macintire, DVM, MS, the skin is thickest dorsally and progressively thins in a ventral direction. The skin DACVIM, DACVECC along the inner aspect of the extremities tends to be thinner than the lateral skin surface areas. -

Abdominal Wound Dehiscence and Incisional Hernias Are Common Problems Cause and Prevention Facing the General Surgeon

ABDOMINAL SURGERY failure of the entire wound with evisceration, or ‘burst Abdominal wound abdomen’. The incidence of abdominal wound dehiscence ranges from 0.25e3% with an associated mortality of up to 25%2,3 and dehiscence and incisional is most often seen at around 1 week post surgery.2,4 Incisional hernia (Figure 1) is a chronic wound failure and hernia presents some time after surgery, often at follow-up clinics or as a new referral. The incidence varies between 5% and 15% David C Bartlett following vertical midline incisions at one year follow up. More Andrew N Kingsnorth than 50% of incisional hernias occur in the first year post- operatively and 90% of incisional hernias occur within three e years of surgery.5 7 Abstract Abdominal wound dehiscence and incisional hernias are common problems Cause and prevention facing the general surgeon. Both can be thought of as forms of ‘wound The causes of acute and chronic wound failure are similar. Poor failure’ and the risk factors are similar for both. Some of these may be surgical technique and wound infection can cause acute dehis- avoided by sound surgical technique and correct patient preparation. The cence; acute dehiscence is the commonest cause of incisional management of wound dehiscence ranges from simple dressings to emer- hernia which is preceded by wound infection in nearly 50%.5 gency surgery to close a ‘burst abdomen’ followed by a period of intensive There are a number of other risk factors that predispose to care. The management of incisional hernias is a much bigger topic and wound failure. -

Retained Sponge: a Rare Complication in Acetabular Osteosinthesis

Send Orders for Reprints to [email protected] The Open Orthopaedics Journal, 2015, 9, (Suppl 1: M7) 321-323 321 Open Access Retained Sponge: A Rare Complication in Acetabular Osteosinthesis Francisco Chana-Rodríguez*,1 Rubén Pérez Mañanes1, José Rojo-Manaute1, Luz María Moran-Blanco2 and Javier Vaquero-Martín1 1Department of Traumatology and Orthopaedic Surgery, General University Hospital Gregorio Marañón, Madrid, Spain 2Department of Radiology. General University Hospital Gregorio Marañón, Madrid, Spain. Abstract: Retained sponges after a surgical treatment of polytrauma may cause a broad spectrum of clinical symptoms and present a difficult diagnostic problem. We report a case of retained surgical sponge in a 35-year-old man transferred from another hospital, that sustained a open acetabular fracture. The fracture was reduced through a limited ilio-inguinal approach. After 4 days, he presented massive wound dehiscence of the surgical approach. An abdominal CT scan showed, lying adjacent to the outer aspect of the left iliac crest, a mass of 10 cm, identified as probable foreign body. The possibility of this rare complication should be in the differential diagnosis of any postoperative patient who presents with pain, infection, or palpable mass. Keywords: Fracture, pelvic, retained, sponge, surgery, treatment. INTRODUCTION After 4 days, he presented with fever and massive wound dehiscence of the surgical approach with abundant exudate Retained sponges after a surgical treatment may cause a (Fig. 2). broad spectrum of clinical symptoms and present a difficult diagnostic problem, so orthopaedic surgeons should be aware of this possibility. We report a case of retained surgical sponge in a patient and illustrate the surgical findings of this infrequent but critical cause of postoperative complications. -

For Personal Use Only

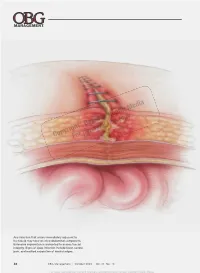

® Dowden Health Media CopyrightFor personal use only Any infection that arises immediately adjacent to the fascia may have an intra-abdominal component. Extensive exploration is warranted to assess fascial integrity. Signs of deep infection include fever, severe pain, and marked separation of wound edges. 42 OBG Management | October 2009 | Vol. 21 No. 10 For mass reproduction, content licensing and permissions contact Dowden Health Media. SurgIcal TechnIQues How to avert postoperative wound complication—and treat it when it occurs Avoid wound infection and dehiscence with the help of thorough preoperative assessment, careful technique, tried-and-true strategies, and a few novel products espite advances in medicine and surgery over the James D. Perkins, MD past century, postoperative wound complication Dr. Perkins is Affiliate Assistant remains a serious challenge. When a complica- Professor of Obstetrics and D Gynecology at the University of tion occurs, it translates into prolonged hospitalization, Mississippi Medical Center in lost time from work, and greater cost to the patient and Jackson, Miss, and Adjunct Clinical Assistant Professor of Obstetrics the health-care system. Classification of and Gynecology at Morehouse Prevention of wound complication begins well before School of Medicine in Atlanta, Ga. surgical wounds He also practices ObGyn at Mallory surgery. Requirements include: page 44 Community Health Center in Canton, • understanding of wound healing (see page 48) and Miss. the classification of wounds (TABLE 1, page 44) Risk factors for Roland A. Pattillo, MD • thorough assessment of the patient for risk factors for poor wound healing impaired wound healing, such as diabetes or use of Dr. Pattillo is Professor of Obstetrics and dehiscence and Gynecology and Director of corticosteroid medication (TABLE 2, page 46) Gynecologic Oncology at Morehouse page 46 School of Medicine in Atlanta, Ga. -

Surgical Wound Dehiscence and Problem Solving - Jon Hall

SURGICAL WOUND DEHISCENCE AND PROBLEM SOLVING - JON HALL Surgical wound management Surgical wounds are those created intentionally by a surgeon for the direct treatment of a condition or to allow access to deeper anatomy for a procedure to be performed. The term ‘surgical incision’ might better describe most elective procedures, as a wound is also used to describe a nonintentional accidental injury (or worse, an intentional malicious one!). Surgical sites heal by the application of one of, or a combination of, approaches: Primary closure –immediate closure of the incision; the vast majority of elective procedures Delayed primary closure – surgical closure before the presence of granulation tissue, having managed the wound open for hours to days Secondary closure – surgical closure over granulation tissue Second intention healing – leave wound healing to proceed normally without further surgical intervention, encouraging conditions that favour uncomplicated healing in a normal timeframe. The vast majority of surgical incisions closed primarily heal without any problems. In particular, those created to access underlying anatomy (e.g. the musckuloskeletal system, abdominal viscera and thoracic organs) that do not involve excision of cutaneous tissue have a very low complication rate. The most common complication is probably infection, which will affect approximately 2-5% of elective procedure. Application of delayed primary, secondary closure and second intention healing are most commonly used for traumatic wounds, or complications of surgical incision or reconstruction dehiscence. However, elective delayed closure or second intention healing can be used in some rare situations (e.g. closure following histopathological confirmation of tumour diagnosis / completeness of excision, second intention healing following tumour excision in awkward locations. -

Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Management of Post-Pneumonectomy Empyema

JSLS Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Management of Post-Pneumonectomy Empyema Francis J. Podbielski, MD, Ari O. Halldorsson, MD, Wickii T. Vigneswaran, MD ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION Background: Post-pneumonectomy empyema is a major Post-pneumonectomy empyema occurs in a small percent- therapeutic challenge in thoracic surgery. The presence or age of patients and continues to be a major therapeutic chal- absence of a concomitant bronchopleural fistula directs lenge. Etiology of this problem includes bronchopleural fis- treatment of this condition. When there is no bron- tulae, wound dehiscence, or a persistent nidus of colonized chopleural fistula the condition is classically treated with pleura. Clinical manifestations with spiking fever, purulent thoracostomy drainage, irrigation and antibiotic instillation sputum production, and generalized malaise are the prelude with closure. This approach is, however, associated with a to appearance of a new air-fluid level or loss of fluid level significant rate of primary failure. Alternative modified and/or loculation in a previously homogeneous hemithorax techniques involve opening the thoracic cavity widely with on chest roentgenogram. Patients rarely present with mild serial debridement followed by interval closure. Multiple constitutional symptoms and wound dehiscence or empye- surgical procedures often require a protracted hospital stay. ma necessitans. Methods: We describe a technique in three patients utiliz- The goals of treatment are control of infection, closure of ing video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for debridement the bronchopleural fistula if present and obliteration of the and closure of the pneumonectomy cavity. cavity. Treatment algorithms segregate post-pneumonecto- my empyema into those with versus those without con- Conclusion: Advantages of this technique include comitant bronchopleural fistula.