In the Public University Classroom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sydney Program Guide

4/23/2021 prtten04.networkten.com.au:7778/pls/DWHPROD/Program_Reports.Dsp_SHAKE_Guide?psStartDate=09-May-21&psEndDate=15-… SYDNEY PROGRAM GUIDE Sunday 09th May 2021 06:00 am Totally Wild CC C Get inspired by all-access stories from the wild side of life! 06:30 am Top Wing (Rpt) G Rod's Beary Brave Save / Race Through Danger Canyon Rod proves that he is a rooster (and not a chicken) as he finds a cub named Baby Bear lost in the Haunted Cave. A jet-flying bat roars into Danger Canyon to show off his prowess. 07:00 am Blaze And The Monster Machines (Rpt) G Treasure Track Blaze, AJ, and Gabby join Pegwheel the Pirate-Truck for an island treasure hunt! Following their treasure map, the friends search jungle beaches and mountains to find where X marks the spot. 07:30 am Paw Patrol (Rpt) G Pups Save The Runaway Turtles / Pups Save The Shivering Sheep Daring Danny X accidently drives off with turtle eggs that Cap'n Turbot had hoped to photograph while hatching. Farmer Al's sheep-shearing machine malfunctions and all his sheep run away. 07:56 am Shake Takes 08:00 am Paw Patrol (Rpt) G Sea Patrol: Pups Save A Frozen Flounder / Pups Save A Narwhal Cap'n Turbot's boat gets frozen in the Arctic Ice. The pups use the Sea Patroller to help guide a lost narwhal back home. 08:30 am The Loud House (Rpt) G Lincoln Loud: Girl Guru / Come Sale Away For a class assignment Lincoln and Clyde must start a business. -

Religion As a Role: Decoding Performances of Mormonism in the Contemporary United States

RELIGION AS A ROLE: DECODING PERFORMANCES OF MORMONISM IN THE CONTEMPORARY UNITED STATES Lauren Zawistowski McCool A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2012 Committee: Dr. Scott Magelssen, Advisor Dr. Jonathan Chambers Dr. Lesa Lockford © 2012 Lauren Zawistowski McCool All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Scott Magelssen, Advisor Although Mormons have been featured as characters in American media since the nineteenth century, the study of the performance of the Mormon religion has received limited attention. As Mormonism (The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints) continues to appear as an ever-growing topic of interest in American media, there is a gap in discourse that addresses the implications of performances of Mormon beliefs and lifestyles as performed by both members of the Church and non-believers. In this thesis, I closely examine HBO’s Big Love television series, the LDS Church’s “I Am a Mormon” media campaign, Mormon “Mommy Blogs” and the personal performance of Mormons in everyday life. By analyzing these performances through the lenses of Stuart Hall’s theories of encoding/decoding, Benedict Anderson’s writings on imagined communities, and H. L. Goodall’s methodology for the new ethnography the aim of this thesis is to fill in some small way this discursive and scholarly gap. The analysis of performances of the Mormon belief system through these lenses provides an insight into how the media teaches and shapes its audience’s ideologies through performance. iv For Caity and Emily. -

The Weird History of Usamerican Fascism: a Guide (1979-2019) Phd in Critical and Cultural Theory 2019 M.C

The Weird History of USAmerican Fascism: A Guide (1979-2019) PhD in Critical and Cultural Theory 2019 M.C. McGrady Summary The future, as ever, can be read in comic books. Foretold by the Dark Age of Comics, the doom that now comes to Earth arrives in the form of self-realizing eschatologies, horrors born out of the rutting between unfettered capitalism and its favorite child, technological hubris. When the Big Two comic book publishers began hiring British and Irish authors en masse over the course of the 1980s, these writers brought with them a critical eye sharpened by the political and economic cruelty of the decade. The victims of the Iron Lady came to the New World and set their sights on the empire of the Teflon President, using superhero stories to explore the ideological weapons deployed in the service of global capitalism. The Weird History of USAmerican Fascism tracks the interrelated networks of popular culture and fascism in the United States to demonstrate the degree to which contemporary USAmerican politics embodies the future that the fictional dystopias of the past warned us about. Although the trans-Atlantic political developments of 2016 and their aftermath have sparked a widespread interest in a resurgent Anglophone fascism and its street-level movements – seen most obviously in the loose collection of white supremacists known as the ‘alt- right’ – this interest has been hamstrung by the historical aversion to a serious study of popular and ‘nerd’ culture during the twentieth century. By paying attention to the conceptual and interpersonal networks that emerged from the comic books and videogames of the 1980s, The Weird History of USAmerican Fascism fills a critical lacuna in cultural theory while correcting recent oversights in the academic analysis of contemporary fascism, providing an essential guide to the past, present, and future of the bizarre world of USAmerican politics. -

Instructor's Guide

DRAWN TO THE GODS Religion and Humor in The Simpsons, South Park, and Family Guy Instructor’s Guide Dives into a new world of religious satire illuminated through the layers of religion and humor that make up the The Simpsons, South Park, and Family Guy. Drawing on the worldviews put forth by three wildly popular animated shows – The Simpsons, South Park, and Family Guy– David Feltmate demonstrates how ideas about religion’s proper place in American society are communicated through comedy. The book includes discussion of a wide range of American religions, including Protestant and Catholic Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Buddhism, Native American Religions, New Religious Movements, “Spirituality,” Hinduism, and Atheism. Along the way, readers are shown that jokes about religion are influential tools for teaching viewers how to interpret and judge religious people and institutions. Feltmate develops a picture of how each show understands 304 pages | Paper | 978-1-4798-9036-1 Religion and communicates what constitutes good religious practice as well as which traditions they seek to exclude on the basis of Contents: race and ethnicity, stupidity, or danger. From Homer Simpson’s • Chapter Summaries with Discussion Questions spiritual journey during a chili-pepper induced hallucination to and Recommended Episodes South Park’s boxing match between Jesus and Satan to Peter • Questions for Reflection Griffin’s worship of the Fonz, each show uses humor to convey • Supplementary Assignments a broader commentary about the role of religion in public life. Through this examination, an understanding of what it means to "Without a doubt, I will use this delightful, well-researched, well-crafted monograph in my media, religion, and popular culture courses. -

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Challenging Christian Liberalism: Religious Minorities and the Public Sphere Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3mf3j1h1 Author Dick, Hannah Publication Date 2016 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Challenging Christian Liberalism: Religious Minorities and the Public Sphere A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Communication by Hannah Dick Committee in charge: Professor John McMurria, Chair Professor John Evans Professor Valerie Hartouni Professor Marcel Hénaff Professor Robert Horwitz 2016 Copyright Hannah Dick, 2016 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Hannah Caitlin Dick is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2016 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ................................................................................................................... iii Table of Contents.............................................................................................................. -

Mormonism? a Student’S Introduction, by Patrick Q

Mormon Studies Review Volume 5 Number 1 Article 15 2018 Review of What is Mormonism? A Student’s Introduction, by Patrick Q. Mason; Mormonism: The Basics, by David J. Howlett and John Charles Duffy Jennifer Graber Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr2 Part of the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Graber, Jennifer (2018) "Review of What is Mormonism? A Student’s Introduction, by Patrick Q. Mason; Mormonism: The Basics, by David J. Howlett and John Charles Duffy," Mormon Studies Review: Vol. 5 : No. 1 , Article 15. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18809/msr.2018.0121 Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr2/vol5/iss1/15 This Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mormon Studies Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Graber: Review of What is Mormonism? Title Review of What is Mormonism? A Student’s Introduction, by Patrick Q. Mason; Mormonism: The Basics, by David J. Howlett and John Charles Duffy Author Jennifer Graber Reference Mormon Studies Review (201 ): 147 151. ISSN 2156-8022 (print), 2156-80305 8 (online)– DOI https://doi.org/10.18809/msr.2018.0121 Published by BYU ScholarsArchive, 2017 1 Mormon Studies Review, Vol. 5 [2017], No. 1, Art. 15 Book Reviews: What is Mormonism?/Mormonism: The Basics 147 church will need to continue to wrestle with how to deal with its past, especially when scholars still have many questions about the historical accuracy of elements of the Book of Mormon. -

Gruda Mpp Me Assis.Pdf

MATEUS PRANZETTI PAUL GRUDA O DISCURSO POLITICAMENTE INCORRETO E DO ESCRACHO EM SOUTH PARK ASSIS 2011 MATEUS PRANZETTI PAUL GRUDA O DISCURSO POLITICAMENTE INCORRETO E DO ESCRACHO EM SOUTH PARK Dissertação apresentada à Faculdade de Ciências e Letras de Assis – UNESP – Universidade Estadual Paulista para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Psicologia (Área de Conhecimento: Psicologia e Sociedade) Orientador: Prof. Dr. José Sterza Justo Trabalho financiado pela CAPES ASSIS 2011 Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação (CIP) Biblioteca da F.C.L. – Assis – UNESP Gruda, Mateus Pranzetti Paul G885d O discurso politicamente incorreto e do escracho em South Park / Mateus Pranzetti Paul Gruda. Assis, 2011 127 f. : il. Dissertação de Mestrado – Faculdade de Ciências e Letras de Assis – Universidade Estadual Paulista Orientador: Prof. Dr. José Sterza Justo. 1. Humor, sátira, etc. 2. Desenho animado. 3. Psicologia social. I. Título. CDD 158.2 741.58 MATEUS PRANZETTI PAUL GRUDA O DISCURSO POLITICAMENTE INCORRETO E DO ESCRACHO EM “SOUTH PARK” Dissertação apresentada à Faculdade de Ciências e Letras de Assis – UNESP – Universidade Estadual Paulista para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Psicologia (Área de Conhecimento: Psicologia e Sociedade) Data da aprovação: 16/06/2011 COMISSÃO EXAMINADORA Presidente: PROF. DR. JOSÉ STERZA JUSTO – UNESP/Assis Membros: PROF. DR. RAFAEL SIQUEIRA DE GUIMARÃES – UNICENTRO/ Irati PROF. DR. NELSON PEDRO DA SILVA – UNESP/Assis GRUDA, M. P. P. O discurso do humor politicamente incorreto e do escracho em South Park. -

1 United States District Court for The

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ________________________________________ ) VIACOM INTERNATIONAL INC., ) COMEDY PARTNERS, ) COUNTRY MUSIC TELEVISION, INC., ) PARAMOUNT PICTURES ) Case No. 1:07-CV-02103-LLS CORPORATION, ) (Related Case No. 1:07-CV-03582-LLS) and BLACK ENTERTAINMENT ) TELEVISION LLC, ) DECLARATION OF WARREN ) SOLOW IN SUPPORT OF Plaintiffs, ) PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION FOR v. ) PARTIAL SUMMARY JUDGMENT ) YOUTUBE, INC., YOUTUBE, LLC, and ) GOOGLE INC., ) Defendants. ) ________________________________________ ) I, WARREN SOLOW, declare as follows: 1. I am the Vice President of Information and Knowledge Management at Viacom Inc. I have worked at Viacom Inc. since May 2000, when I was joined the company as Director of Litigation Support. I make this declaration in support of Viacom’s Motion for Partial Summary Judgment on Liability and Inapplicability of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act Safe Harbor Defense. I make this declaration on personal knowledge, except where otherwise noted herein. Ownership of Works in Suit 2. The named plaintiffs (“Viacom”) create and acquire exclusive rights in copyrighted audiovisual works, including motion pictures and television programming. 1 3. Viacom distributes programs and motion pictures through various outlets, including cable and satellite services, movie theaters, home entertainment products (such as DVDs and Blu-Ray discs) and digital platforms. 4. Viacom owns many of the world’s best known entertainment brands, including Paramount Pictures, MTV, BET, VH1, CMT, Nickelodeon, Comedy Central, and SpikeTV. 5. Viacom’s thousands of copyrighted works include the following famous movies: Braveheart, Gladiator, The Godfather, Forrest Gump, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, Top Gun, Grease, Iron Man, and Star Trek. -

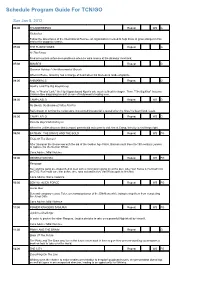

Program Guide Report

Schedule Program Guide For TCN/GO Sun Jan 8, 2012 06:00 THUNDERBIRDS Repeat WS G Richochet Follow the adventures of the International Rescue, an organisation created to help those in grave danger in this marionette puppetry classic. 07:00 THE FLINTSTONES Repeat G At The Races Fred encounters unforeseen problems when he wins money at the dinosaur racetrack. 07:30 SMURFS Repeat G Gnoman Holiday / The Monumental Grouch When in Rome, Grouchy has a change of heart when his likeness is made of granite. 08:00 ANIMANIACS Repeat G Noah's Lark/The Big Kiss/Hiccup First, in "Noahs' Lark," the Hip Hippos board Noah's ark, much to Noah's chagrin. Then, "The Big Kiss" features Chicken Boo disguising himself as one of Hollywood's leading men. 08:30 CAMP LAZLO Repeat WS G No Beads, No Business!/ Miss Fru Fru Raj's dream of turning the camp store into something special is tested when he hires his best friend, Lazlo. 09:00 CAMP LAZLO Repeat WS G Parents Day/ Club Kidney-ki When the Jellies discover that Lumpus' parents did not come to visit him at Camp, they try to set things right. 09:30 BATMAN: THE BRAVE AND THE BOLD Repeat WS PG Trials Of The Demon! After taking on the Scarecrow with the aid of the Golden Age Flash, Batman must travel to 19th century London to capture the Gentleman Ghost. Cons.Advice: Mild Violence 10:00 GENERATOR REX Repeat WS PG Rampage Rex and the gang are dispatched to deal with a commotion going on at the port. -

Why the Book of Mormon (The Musical) Is Awesomely Lame

Why The Book of Mormon (the Musical) Is Awesomely Lame Never mind the Tony awards and all the acclaim, Broadway’s best is not all that By Jared Farmer June 12, 2011 The Book of Mormon cleaned up at this year’s Tony Awards, winning nine of the 14 awards it was nominated for, including Best Musical. But tonight’s success is hardly unexpected, cap- ping off, as it does, an extraordinary season of critical adula- tion. What’s going on? Why has a good-not-great religious sat- ire from the creators of South Park received rapturous praise from the whole canon of media tastemakers? It may be true that The Book of Mormon is the second best musical début (behind American Idiot) on the Great White Way in recent memory, but that’s really not saying much. In a season devoted mainly to re-runs, revivals, and adaptations, The Book of Mormon stands out for being a first-run play with an original score and book. Also, while the musical adheres to 1950s Broadway conventions—tunefulness, campiness, and uplift—it’s modishly vulgar. The Book of Arnold? The plot concerns two unprepared and ill-paired missionaries, a pious hunk and a delusional geek, sent from Utah to Uganda. There the rural villagers suffer from AIDS, dysentery, and political violence. The Ugandans say they have no use for 1 this American religion; it doesn’t help their situation. But genitalia and rape babies to cure their AIDS (a now outdated when the chubby, bespectacled geek—a Mormon who has reference to a folk-belief about “virgin-cleansing” that began never read the Book of Mormon—invents “scriptural” stories in South Africa). -

Mormonism on the Internet: Now Everybody Has a Printing Press

Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011 Volume 9 Number 1 Article 18 1997 Mormonism on the Internet: Now Everybody Has a Printing Press Gregory H. Taggart Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Taggart, Gregory H. (1997) "Mormonism on the Internet: Now Everybody Has a Printing Press," Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011: Vol. 9 : No. 1 , Article 18. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr/vol9/iss1/18 This Study Aid is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011 by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title Mormonism on the Internet: Now Everybody Has a Printing Press. Author(s) Gregory H. Taggart Reference FARMS Review of Books 9/1 (1997): 161–74. ISSN 1099-9450 (print), 2168-3123 (online) Abstract Mormon websites include those with links to other sites and those with something substantive to offer. Numerous links to substantive websites are given. Mormonism on the Internet: Now Everybody Has a Printing Press Reviewed by Gregory H. Taggart What to do? The information superhighway is true to its name. tt is loaded with information. both good and bogus. The amount of information clogging the highway is worse than a busy freeway interchange and increases daily. Unfortunately. the rat io of good to bad, or at least valuable to worthless, is not very good. -

Tracing LDS Families

RESEARCH OUTLINE Tracing LDS Families CONTENTS publications, see the Family History Materials List (34083). In this outline the distribution center Introduction ............................. 1 item number is listed in parentheses that follow Basic Search Strategies.................... 3 the titles of publications on the materials list. Records Selection Table ................... 7 Archives and Libraries .................... 8 Using This Outline Biography ............................. 11 Census................................ 13 This section and the “Basic Search Strategies” and Church History ......................... 14 “Records Selection Table” sections of this outline Church Records......................... 15 describe the records at the library and suggest Colonization............................15 ways to do research effectively. This section Directories............................. 17 briefly describes major collections of records available at the Family History Library and how to Emigration and Immigration............... 17 ™ Genealogy ............................. 22 use FamilySearch and the Family History Historical Geography..................... 25 Library Catalog to find Latter-day Saint ancestors. History................................ 27 The Records Selection Table helps you choose Membership Records..................... 31 records to search based on the kind of information Military Records ........................ 35 you want to find about an ancestor. Missionaries............................ 38 Newspapers...........................