TOCC0308DIGIBKLT.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The AMICA BULLETIN AUTOMATIC MUSICAL INSTRUMENT COLLECTORS’ ASSOCIATION JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2002 VOLUME 39, NUMBER 1 Mooluriil's MAGAZINE

The AMICA BULLETIN AUTOMATIC MUSICAL INSTRUMENT COLLECTORS’ ASSOCIATION JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2002 VOLUME 39, NUMBER 1 MoOLURIil'S MAGAZINE The Self-Playing Piano is It People who have watched these things closely have noticed that popular favor is toward the self-playing piano. A complete piano which will ornament your drawing-room, which can be played in the ordinary way by human fingers, or which. -'\ can be played by a piano player concealed inside the case, is the most popular musical instrument in the world to-day. The Harmonist Self-Playing Piano is the instrument which best meets these condi tions. The piano itself is perfect in tone and workmanship. The piano player at tachment is inside, is operated by perforated music, adds nothing to the size of the piano. takes up no room whatever, is always ready, is never in the way. We want everyone who is thinking of buying a piano to consider the great advan tage of getting a Harmonist, which combines the piano and the piano player both. It costs but little more than a good piano. but it is ten times as useful and a hundred times as entertaining. Write for particulars. ROTH ~ENGELHARDT Proprietors Peerless Piano Player Co. Windsor Aroade. Fifth Ave.. New York Please mention McClure·s when you write to ad"crtiscrt. 77 THE AMICA BULLETIN AUTOMATIC MUSICAL INSTRUMENT COLLECTORS' ASSOCIATION Published by the Automatic Musical Instrument Collectors’ Association, a non-profit, tax exempt group devoted to the restoration, distribution and enjoyment of musical instruments using perforated paper music rolls and perforated music books. -

Elizabeth Joy Roe, Piano

The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts STEPHEN A. SCHWARZMAN , Chairman MICHAEL M. KAISER , President TERRACE THEATER Saturday Evening, October 31, 2009, at 7:30 presents Elizabeth Joy Roe, Piano BACH/SILOTI Prelude in B minor CORIGLIANO Etude Fantasy (1976) For the Left Hand Alone Legato Fifths to Thirds Ornaments Melody CHOPIN Nocturne in C-sharp minor, Op. 27, No. 1 WAGNER/LISZT Isoldens Liebestod RAVEL La Valse Intermission MUSSORGSKY Pictures at an Exhibition Promenade The Gnome Promenade The Old Castle Promenade Tuileries The Ox-Cart Promenade Ballet of the Unhatched Chicks Samuel Goldenberg and Schmuyle Promenade The Market at Limoges (The Great News) The Catacombs With the Dead in a Dead Language Baba-Yaga’s Hut The Great Gate of Kiev Elizabeth Joy Roe is a Steinway Artist Patrons are requested to turn off pagers, cellular phones, and signal watches during performances. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not allowed in this auditorium. Notes on the Program By Elizabeth Joy Roe Prelude in B minor Liszt and Debussy. Yet Corigliano’s etudes JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH ( 1685 –1750) are distinctive in their effective synthesis of trans. ALEXANDER SILOTI (1863 –1945) stark dissonance and an expressive landscape grounded in Romanticism. Alexander Siloti, the legendary Russian pianist, The interval of a second—and its inversion composer, conductor, teacher, and impresario, and expansion to sevenths and ninths—is the was the bearer of an impressive musical lineage. connective thread between the etudes; its per - He studied with Franz Liszt and was the cousin mutations supply the foundation for the work’s and mentor of Sergei Rachmaninoff. -

Rachmaninoff's Early Piano Works and the Traces of Chopin's Influence

Rachmaninoff’s Early Piano works and the Traces of Chopin’s Influence: The Morceaux de Fantaisie, Op.3 & The Moments Musicaux, Op.16 A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Division of Keyboard Studies of the College-Conservatory of Music by Sanghie Lee P.D., Indiana University, 2011 B.M., M.M., Yonsei University, Korea, 2007 Committee Chair: Jonathan Kregor, Ph.D. Abstract This document examines two of Sergei Rachmaninoff’s early piano works, Morceaux de Fantaisie, Op.3 (1892) and Moments Musicaux, Opus 16 (1896), as they relate to the piano works of Frédéric Chopin. The five short pieces that comprise Morceaux de Fantaisie and the six Moments Musicaux are reminiscent of many of Chopin’s piano works; even as the sets broadly build on his character genres such as the nocturne, barcarolle, etude, prelude, waltz, and berceuse, they also frequently are modeled on or reference specific Chopin pieces. This document identifies how Rachmaninoff’s sets specifically and generally show the influence of Chopin’s style and works, while exploring how Rachmaninoff used Chopin’s models to create and present his unique compositional identity. Through this investigation, performers can better understand Chopin’s influence on Rachmaninoff’s piano works, and therefore improve their interpretations of his music. ii Copyright © 2018 by Sanghie Lee All rights reserved iii Acknowledgements I cannot express my heartfelt gratitude enough to my dear teacher James Tocco, who gave me devoted guidance and inspirational teaching for years. -

Lunchtime Concert Brought to Light Elizabeth Layton Violin Michael Ierace Piano Friday 31 July, 1:10Pm

Michael Ierace has been described as a ‘talent to watch’ and his playing as ‘revelatory’. Born and raised in Adelaide, he completed his university education through to Honours level studying with Stefan Ammer and Lucinda Collins. Michael has had much success in local and national Australian competitions including winning The David Galliver Award, The Geoffrey Parsons Award, The MBS Young Performers Award and was a major prize winner in the Australian National Piano Award. In 2009, he made his professional debut with the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra in the presence of the Premier of South Australia and the Polish Ambassador. In 2007, he received the prestigious Elder Overseas Scholarship from the Adelaide University. This enabled him to move to London and study at the Royal College of Music (RCM) with Professor Andrew Ball. He was selected as an RCM Rising Star and was awarded the Hopkinson Silver medal in the RCM’s Chappell Competition. From 2010-12, he was on staff as a Junior Fellow in Piano Accompaniment. In the Royal Over-Seas League Annual Music Competition, he won the Keyboard Final and the Accompanist Prize – the only pianist in the competition's distinguished history to have received both awards. In the International Haverhill Sinfonia Soloists Competition, he took second place plus many specialist awards. Michael has performed extensively throughout London and the UK and twice at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival. Much sort after as an associate artist for national and international guests, Michael is currently a staff pianist at the Elder Conservatorium. Lunchtime Concert Brought to Light Elizabeth Layton violin Michael Ierace piano Friday 31 July, 1:10pm PROGRAM Also notable was his relationship with his young cousin, Sergei Rachmaninoff. -

An Annotated Catalogue of the Major Piano Works of Sergei Rachmaninoff Angela Glover

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2003 An Annotated Catalogue of the Major Piano Works of Sergei Rachmaninoff Angela Glover Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MUSIC AN ANNOTATED CATALOGUE OF THE MAJOR PIANO WORKS OF SERGEI RACHMANINOFF By ANGELA GLOVER A Treatise submitted to the School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2003 The members of the Committee approve the treatise of Angela Glover defended on April 8, 2003. ___________________________________ Professor James Streem Professor Directing Treatise ___________________________________ Professor Janice Harsanyi Outside Committee Member ___________________________________ Professor Carolyn Bridger Committee Member ___________________________________ Professor Thomas Wright Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract………………………………………………….............................................. iv INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………………. 1 1. MORCEAUX DE FANTAISIE, OP.3…………………………………………….. 3 2. MOMENTS MUSICAUX, OP.16……………………………………………….... 10 3. PRELUDES……………………………………………………………………….. 17 4. ETUDES-TABLEAUX…………………………………………………………… 36 5. SONATAS………………………………………………………………………… 51 6. VARIATIONS…………………………………………………………………….. 58 BIBLIOGRAPHY…………………………………………………………………. -

The Fourteenth Season: Russian Reflections July 15–August 6, 2016 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Experience the Soothing Melody STAY with US

The Fourteenth Season: Russian Reflections July 15–August 6, 2016 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Experience the soothing melody STAY WITH US Spacious modern comfortable rooms, complimentary Wi-Fi, 24-hour room service, fitness room and a large pool. Just two miles from Stanford. BOOK EVENT MEETING SPACE FOR 10 TO 700 GUESTS. CALL TO BOOK YOUR STAY TODAY: 650-857-0787 CABANAPALOALTO.COM DINE IN STYLE Chef Francis Ramirez’ cuisine centers around sourcing quality seasonal ingredients to create delectable dishes combining French techniques with a California flare! TRY OUR CHAMPAGNE SUNDAY BRUNCH RESERVATIONS: 650-628-0145 4290 EL CAMINO REAL PALO ALTO CALIFORNIA 94306 Music@Menlo Russian Reflections the fourteenth season July 15–August 6, 2016 D AVID FINCKEL AND WU HAN, ARTISTIC DIRECTORS Contents 2 Season Dedication 3 A Message from the Artistic Directors 4 Welcome from the Executive Director 4 Board, Administration, and Mission Statement 5 R ussian Reflections Program Overview 6 E ssay: “Natasha’s Dance: The Myth of Exotic Russia” by Orlando Figes 10 Encounters I–III 13 Concert Programs I–VII 43 Carte Blanche Concerts I–IV 58 Chamber Music Institute 60 Prelude Performances 67 Koret Young Performers Concerts 70 Master Classes 71 Café Conversations 72 2016 Visual Artist: Andrei Petrov 73 Music@Menlo LIVE 74 2016–2017 Winter Series 76 Artist and Faculty Biographies A dance lesson in the main hall of the Smolny Institute, St. Petersburg. Russian photographer, twentieth century. Private collection/Calmann and King Ltd./Bridgeman Images 88 Internship Program 90 Glossary 94 Join Music@Menlo 96 Acknowledgments 101 Ticket and Performance Information 103 Map and Directions 104 Calendar www.musicatmenlo.org 1 2016 Season Dedication Music@Menlo’s fourteenth season is dedicated to the following individuals and organizations that share the festival’s vision and whose tremendous support continues to make the realization of Music@Menlo’s mission possible. -

Toccata Classics TOCC 0127 Notes

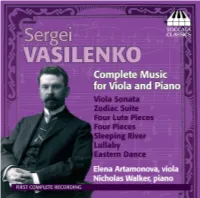

SERGEI VASILENKO AND THE VIOLA by Elena Artamonova The viola is occasionally referred to as ‘the Cinderella of instruments’ – and, indeed, it used to take a fairy godmother of a player to allow this particular Cinderella to go to the ball; the example usually cited in the liberation of the viola in a solo role is the British violist Lionel Tertis. Another musician to pay the instrument a similar honour – as a composer rather than a player – was the Russian Sergei Vasilenko (1872–1956), all of whose known compositions for viola, published and unpublished, are to be heard on this CD, the fruit of my investigations in libraries and archives in Moscow and London. None is well known; some are not even included in any of the published catalogues of Vasilenko’s music. Only the Sonata was recorded previously, first in the 1960s by Georgy Bezrukov, viola, and Anatoly Spivak, piano,1 and again in 2007 by Igor Fedotov, viola, and Leonid Vechkhayzer, piano;2 the other compositions receive their first recordings here. Sergei Nikiforovich Vasilenko had a long and distinguished career as composer, conductor and pedagogue in the first half of the twentieth century. He was born in Moscow on 30 March 1872 into an aristocratic family, whose inner circle of friends consisted of the leading writers and artists of the time, but his interest in music was rather capricious in his early childhood: he started to play piano from the age of six only to give it up a year later, although he eventually resumed his lessons. In his mid-teens, after two years of tuition on the clarinet, he likewise gave it up in favour of the oboe. -

The Development of the Russian Piano Concerto in the Nineteenth Century Jeremy Paul Norris Doctor of Philosophy Department of Mu

The Development of the Russian Piano Concerto in the Nineteenth Century Jeremy Paul Norris Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music 1988 December The Development of the Russian Piano Concerto in the Nineteenth Century Jeremy Paul Norris The Russian piano concerto could not have had more inauspicious beginnings. Unlike the symphonic poem (and, indirectly, the symphony) - genres for which Glinka, the so-called 'Father of Russian Music', provided an invaluable model: 'Well? It's all in "Kamarinskaya", just as the whole oak is in the acorn' to quote Tchaikovsky - the Russian piano concerto had no such indigenous prototype. All that existed to inspire would-be concerto composers were a handful of inferior pot- pourris and variations for piano and orchestra and a negligible concerto by Villoing dating from the 1830s. Rubinstein's five con- certos certainly offered something more substantial, as Tchaikovsky acknowledged in his First Concerto, but by this time the century was approaching its final quarter. This absence of a prototype is reflected in all aspects of Russian concerto composition. Most Russian concertos lean perceptibly on the stylistic features of Western European composers and several can be justly accused of plagiarism. Furthermore, Russian composers faced formidable problems concerning the structural organization of their concertos, a factor which contributed to the inability of several, including Balakirev and Taneyev, to complete their works. Even Tchaikovsky encountered difficulties which he was not always able to overcome. The most successful Russian piano concertos of the nineteenth century, Tchaikovsky's No.1 in B flat minor, Rimsky-Korsakov's Concerto in C sharp minor and Balakirev's Concerto in E flat, returned ii to indigenous sources of inspiration: Russian folk song and Russian orthodox chant. -

Rachmaninoff and the Flexibility of the Score: Issues Regarding Performance Practice

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2018 Rachmaninoff and the Flexibility of the Score: Issues Regarding Performance Practice Tanya Gabrielian The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2762 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] RACHMANINOFF AND THE FLEXIBILITY OF THE SCORE: ISSUES REGARDING PERFORMANCE PRACTICE by TANYA GABRIELIAN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts, The City University of New York 2018 Ó 2018 TANYA GABRIELIAN All Rights Reserved ii Rachmaninoff and the Flexibility of the Score: Issues Regarding Performance Practice by Tanya Gabrielian This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Music in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. Date Anne Swartz Chair of Examining Committee Date Norman Carey Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Geoffrey Burleson Sylvia Kahan Ursula Oppens THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Rachmaninoff and the Flexibility of the Score: Issues Regarding Performance Practice by Tanya Gabrielian Advisor: Geoffrey Burleson Sergei Rachmaninoff’s piano music is a staple of piano literature, but academia has been slower to embrace his works. Because he continued to compose firmly in the Romantic tradition at a time when Debussy, Stravinsky, and Schoenberg variously represented the vanguard of composition, Rachmaninoff’s popularity has consequently not been as robust in the musicological community. -

A. Siloti, a Piano Player and Music Teacher: Emigration from Russia and Peculiarities of Creative Activity in the USA (1921 to 1945)

International Journal of Literature and Arts 2021; 9(4): 197-206 http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/ijla doi: 10.11648/j.ijla.20210904.19 ISSN: 2331-0553 (Print); ISSN: 2331-057X (Online) A. Siloti, a Piano Player and Music Teacher: Emigration from Russia and Peculiarities of Creative Activity in the USA (1921 to 1945) Kulish Mariya Institute of Art, Boris Grinchenko Kiev University, Kiev, Ukraine Email address: To cite this article: Kulish Mariya. A. Siloti, a Piano Player and Music Teacher: Emigration from Russia and Peculiarities of Creative Activity in the USA (1921 to 1945). International Journal of Literature and Arts. Vol. 9, No. 4, 2021, pp. 197-206. doi: 10.11648/j.ijla.20210904.19 Received: August 2, 2021; Accepted: August 16, 2021; Published: August 23, 2021 Abstract: The purpose of the study is to reveal three key vectors of activity of A. Siloti as an outstanding representative of the Russian emigre community during his residing in emigration in the USA. These are concert, teaching and editorial activities. A. Siloti belonged to the first, so-called post-October wave of emigration when arrived in the USA in 1921. The main reasons of his emigration were dangerous problems with Bolshevik`s power. He emigrated firstly to Finland, then were European counties, which were famous for Russian emigrants. After three years of wandering, which were marked by A. Siloti`s only concert activities he, at least, began his creative way in USA. So, this article specifies the contribution A. Siloti made both to the cultural environment of the USA at the beginning of the twentieth century, and to the performing and teaching activities of musicians of the first wave of emigration. -

Piano Sonatas

PIANO SONATAS Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Piano Sonata No. 27 in E minor, Op. 90 13:08 1 I. Mit Lebhaftigkeit und durchaus mit Empfindung und Ausdruck 6:03 2 II. Nicht zu geschwind und sehr singbar vorzutragen 7:05 Alexander Scriabin (1872-1915) 3 Piano Sonata No. 10, Op. 70 12:57 Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953) Piano Sonata No. 2 in D minor, Op. 14 20:55 4 I. Allegro non troppo — più mosso — tempo primo 6:34 5 II. Scherzo: Allegro marcato 2:32 6 III. Andante 6:11 7 IV. Vivace — moderato — vivace 5:37 bonus tracks: Claude Debussy (1862-1918) Estampes 16:00 8 I. Pagodes 6:27 9 II. La soirée dans Grenade 5:18 10 III. Jardins sous la pluie 4:14 total playing time: 63:01 NATALIA ANDREEVA piano The Music I recorded these piano sonatas and “Estampes” at different stages of my life. It was a long journey: practicing, performing, teaching and doing the research… all helped me to create my own mental pictures and images of these piano masterpieces. Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 27 in E minor, Op. 90 “Why do I write? What I have in my heart must come out; and that is why I compose.” Those are famous words of the composer.1 There is a 4-5 year gap between Beethoven’s Piano Sonata Op. 81a (completed in 1809) and Op. 90, composed in 1814. The Canadian pianist Anton Kuetri (who has recorded Beethoven’s complete Piano Sonatas) wrote: “For four years Beethoven wrote no sonatas, symphonies or string quartets. -

The Critical Reception of Alexei Stanchinsky* Akvilė Stuart1 Болесни Геније?

DOI https://doi.org/10.2298/MUZ2130019S UDC 78.071.1 Станчински А. В. A Sick Genius? The Critical Reception of Alexei Stanchinsky* ______________________________ Akvilė Stuart1 PhD Candidate, Royal Birmingham Conservatoire, Birmingham City University, United Kingdom Болесни геније? Критичка рецепција Алексеја Станчињског _______________________________ Аквиле Стјуарт Докторандкиња, Краљевски конзерваторијум у Бирмингему, Универзитет у Бирмингему, Уједињено Kраљевство Received: 1 March 2021 Accepted: 1 May 2021 Original scientific paper Abstract This article examines the critical reception of the Russian composer Alexei Stanchinsky (1888–1914). It focuses on the critical reviews published in Rus- sian newspapers and musical periodicals during Stanchinsky’s lifetime. Its find- ings are a result of original archival research conducted in Moscow in 2019. This study shows that Stanchinsky’s work received a more mixed reception during his lifetime than previously claimed. As such, it provides a more nuanced insight into Stanchinsky’s reception, as well as the views and prejudices of early 20th century Russian music critics. Keywords: Alexei Stanchinsky, criticism, reception, Imperial Russia, mental illness. * This work was supported by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, UK. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the British Association of Slavonic and East European Studies (BASEES) – Russian and East European Music (REEM) Study Group Conference 2019 on 12 October 2019 at Durham University, UK. 1 [email protected] 20 МУЗИКОЛОГИЈА / MUSICOLOGY 30-2021 Апстракт У овом чланку се испитује критичка рецепција руског композитора Алексеја Владимировича Станчињског (1888–1914). У средишту пажње су критички прикази објављени у руској штампи и музичкој периодици током композиторовог живота. Овде презентирани увиди представљају резултат архивског рада спроведеног у Москви 2019.