Hugo Hamilton's Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Isaiah Berlin Papers (PDF)

Catalogue of the papers of Sir Isaiah Berlin, 1897-1998, with some family papers, 1903-1972 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on 2019-10-14 Finding aid written in English Bodleian Libraries Weston Library Broad Street Oxford, , OX1 3BG [email protected] https://www.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/weston Catalogue of the papers of Sir Isaiah Berlin, 1897-1998, with some family papers, 1903-1972 Table Of Contents Summary Information .............................................................................................................................. 4 Language of Materials ......................................................................................................................... 4 Overview ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Biographical / Historical ..................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Contents ............................................................................................................................. 5 Arrangement ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Custodial History ................................................................................................................................. 5 Immediate Source of Acquisition ....................................................................................................... -

The Role of Ultra-Orthodox Political Parties in Israeli Democracy

Luke Howson University of Liverpool The Role of Ultra-Orthodox Political Parties in Israeli Democracy Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy By Luke Howson July 2014 Committee: Clive Jones, BA (Hons) MA, PhD Prof Jon Tonge, PhD 1 Luke Howson University of Liverpool © 2014 Luke Howson All Rights Reserved 2 Luke Howson University of Liverpool Abstract This thesis focuses on the role of ultra-orthodox party Shas within the Israeli state as a means to explore wider themes and divisions in Israeli society. Without underestimating the significance of security and conflict within the structure of the Israeli state, in this thesis the Arab–Jewish relationship is viewed as just one important cleavage within the Israeli state. Instead of focusing on this single cleavage, this thesis explores the complex structure of cleavages at the heart of the Israeli political system. It introduces the concept of a ‘cleavage pyramid’, whereby divisions are of different saliency to different groups. At the top of the pyramid is division between Arabs and Jews, but one rung down from this are the intra-Jewish divisions, be they religious, ethnic or political in nature. In the case of Shas, the religious and ethnic elements are the most salient. The secular–religious divide is a key fault line in Israel and one in which ultra-orthodox parties like Shas are at the forefront. They and their politically secular counterparts form a key division in Israel, and an exploration of Shas is an insightful means of exploring this division further, its history and causes, and how these groups interact politically. -

Complaint Hugo Boss

Kampagne für Saubere Kleidung Clean Clothes Campaign Entwicklungspolitisches Netzwerk Sachsen e.V. ENS Dr. Bettina Musiolek Dresden, 13. November 2014 To Christoph Auhagen, Chief Brand Officer HUGO BOSS AG Dieselstrasse 12 , 72555 Metzingen [email protected] cc RA Carsten Thiel von Herff, Hugo Boss Ombudsperson Detmolder Straße 30, 33604 Bielefeld 0049/5215573330 [email protected] Complaint Poverty wages of workers producing Hugo Boss products Rationale: Europe plays an important role in the production and sales of Boss’ products According to Hugo Boss’ Sustainability Report 2013, „the Group operates production facilities in Izmir (Turkey), which is its largest in-house production location, as well as in Cleveland (USA), Metzingen (Germany), Radom (Poland) and Morrovalle (Italy).“ „The main business operations of the HUGO BOSS Group are concentrated within Europe, where the primary administrative and production sites are located.” „The Company has identified attractive growth opportunities in Eastern Europe.” „Production, logistics and administration locations in Europe (…) represent 55% of the Group's employees.” The company’s claim with regard to remuneration „The HUGO BOSS Group’s remuneration system is designed to ensure the fair and transparent compensation of employees and promote a culture of performance and dedication.” „At international locations the companies comply with the corresponding national framework conditions with regard to their pay structure. As such, entry-level wages must be at least equivalent to the statutory minimum wage.” (p. 23, Sustainability Report). The report does not account for any reality checks of these claims, let alone an indepent verification. CCC research on wages of Hugo Boss workers The Clean Clothes Campaign researched in Turkey, Central, East and South East Europe in order to find out, which conditions workers who make Hugo Boss’ clothes find themselves in – with specific focus on remuneration. -

Download Our Menu

WELCOME TO BREAKFAST // LUNCH // DINNER Each meal is prepared to order, from scratch, using consciously sourced whole foods & plant based ingredients with a focus on GMO-free, sustainable and organic items. Balanced choices to create delicious options for vegan, vegetarian and gluten-free diets so that everyone in your family can eat at the same table together. ORDER FOR PICK UP OR DELIVERY VIA – WWW.HUGOSRESTAURANT.COM – FLAT RATE DELIVERY - NO SPECIAL CHARGES OR & & WEST HOLLYWOOD | 8401 SANTA MONICA BLVD. | 323.654.3993 MON-THUR 9-9 | FRI 9-10 | SAT 8-10 | SUN 8-9 & STUDIO CITY | 12851 RIVERSIDE DR | 818.761.8985 MON-FRI 9-9 | SAT & SUN 8-9 hugosrestaurant hugosrestaurants FOR NEWS & DEALS BEVERAGES CHAI & TEA LATTES COFFEES WHOLE, NONFAT, OAT, SOY, RICE OR ALMOND MILK HOUSE COFFEE 3.75 HOUSE CHAI LATTE DECAF COFFEE 3.75 Ayurvedic spices with rooibos, raw cane sugar and steamed milk ESPRESSO 3.50 of choice. Caffeine free. 4.75 CAPPUCCINO 4.75 BLACK TEA CHAI LATTE CAFFE MOCHA 5.00 House Chai, black tea, raw cane sugar and steamed milk of choice. 4.75 CAFFE LATTE 4.75 MATCHA LATTE HORCHATA LATTE 5.00 Matcha green tea steamed with rice milk. 5.25 EXTRA SHOT 1.00 ROOIBOS AFRICANA LATTE LEMONADES With cornflower, blue mallow, vanilla and steamed milk of choice. 4.75 RED HOT LATTE OLD FASHIONED 4.00 Fresh ground sweet & spicy Saigon Cinnamon with steamed milk of choice. 4.75 MATCHA GREEN TEA 5.00 VEDIC LATTE ORGANIC STRAWBERRY 5.00 Turmeric, ginger, cardamom and hint of nutmeg and long pepper. -

Victor Hugo's Estimate of Germany

5 $1.00 per Year OCTOBER, 1915 Price, 10 Cents tlbe ©pen Court A MONTHLY MAGAZINE H)evotc& to tbc Science ot IReU^ion, tbe IReltafon ot Science, anb tbe Ertension of tbe IReligious parliament l^ea Founded by Edward C. Hegeler. THE STATUE OF VENUS BY KALAMIS. (See page 613.) Zbc ®pcn Court IPublisbfna (Tompanie CHICAGO Per copy, 10 cents (sixpence). Yearly, $1.00 (in the U.P.U., Ss. 6A). Entered u Sec«od-CIau Matter March 26, 18971 at the Post Office at Chicago, III., under Act of March 3> i>79 Copyright by The Open Court Publishing Company, 191 $1.00 per Year OCTOBER, 1915 Price, 10 Cents tlbe ©pen Court A MONTHLY MAGAZINE H)cvote^ to tbc Science ot IReltgton, tbe IReliafon ot Science, anb tbe Brtension ot tbe IReligious parliament 1&ea Founded by Edward C. Hegeler. THE STATUE OF VENUS BY KALAMIS. (See page 613.) Xtbe ©pen Court pubUsbing Companie CHICAGO Per copy, 10 cents (sixpence). Yearly, $1.00 (in the U.P.U., Ss. 6d.). Entered as Sccend-Qua Matter March 36, 1897. at the Post Office at Chicago, lU., tinder Act of March 3, 1S79 CopTTight by The Open Court Publishing Company, 1915 VOL. XXIX (No. 10) OCTOBER, 1915 NO. 713 CONTENTS: FAGI Frontispiece. The Venus of Praxiteles. Victor Hugo's Estimate of Germany 577 Open Letters from M. Paul Hyacinthe Loyson 583 The "Open Mind" in "The Open Court." C. Marsh Beadnell 590 The Future of Socialism. Frank MacDonald 597 Aphrodite (With illustrations). Paul Carus 608 The Religions of Comte and Spencer. -

4. the Nazis Take Power

4. The Nazis Take Power Anyone who interprets National Socialism as merely a political movement knows almost nothing about it. It is more than a religion. It is the determination to create the new man. ADOLF HITLER OVERVIEW Within weeks of taking office, Adolf Hitler was altering German life. Within a year, Joseph Goebbels, one of his top aides, could boast: The revolution that we have made is a total revolution. It encompasses every aspect of public life from the bottom up… We have replaced individuality with collective racial consciousness and the individual with the community… We must develop the organizations in which every individual’s entire life will be regulated by the Volk community, as represented by the Party. There is no longer arbitrary will. There are no longer any free realms in which the individual belongs to himself… The time of personal happiness is over.1 How did Hitler do it? How did he destroy the Weimar Republic and replace it with a totalitarian government – one that controls every part of a person’s life? Many people have pointed out that he did not destroy democracy all at once. Instead, he moved gradually, with one seemingly small compromise leading to another and yet another. By the time many were aware of the danger, they were isolated and alone. This chapter details those steps. It also explores why few Germans protested the loss of their freedom and many even applauded the changes the Nazis brought to the nation. Historian Fritz Stern offers one answer. “The great appeal of National Socialism – and perhaps of every totalitarian dictatorship in this century – was the promise of absolute authority. -

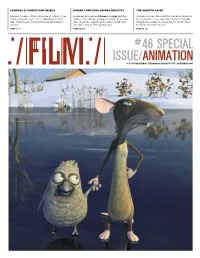

46 Special Issue/Animation

PROFILES & PRODUCTION MILIEUS DANISH COMPUTER GAMING INDUSTRY THE GROWTH LAYER Denmark, a nation of five million, has an output of one Breakaway hits such as Hitman and Hugo put Den- The National Film School and the Animation Workshop animated feature a year, and an abundance of short mark on the computer gaming world map. Now a new are involved in a close, smoothly running partnership films. FILM presents the flourishing Danish animation wave of Danish computer game makers is following which develops skilled professionals for the Northern industry. suit with a slew of fresh gaming ideas. European animation industry. PAGE 3 –17 PAGE 20 –22 PAGE 23 –25 # 46 SPECIAL l1l ISSUE/ANIMATION FILM IS PUBLISHED BY THE DANISH FILM INSTITUTE, SEPTEMBER 2005 FILM #46 SPECIAL ISSUE / ANIMATION / PAGE 2 l1l SPECIAL ISSUE / ANIMATION INSIDE ����������������������������� ������������������������������� ���������������� �������������������������������������������������������� ����������������������������������������������� ���������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������ 3 A. FILM / The Danish production company that brought us Help! I’m a Fish and Terkel �������������������������� ������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������ ���������������������������������������� ���������������������������� ������ ��� ������� ��� ������� ��� in -

Drama Directory 2014

2014 UPDATE CONTENTS Acknowlegements ..................................................... 2 Latvia .......................................................................... 122 Introduction ................................................................. 3 Lithuania ................................................................... 125 Luxembourg ............................................................ 131 Austria .......................................................................... 4 Malta .......................................................................... 133 Belgium ...................................................................... 10 Netherlands ............................................................. 135 Bulgaria ....................................................................... 21 Norway ..................................................................... 145 Cyprus ......................................................................... 26 Poland ........................................................................ 151 Czech Republic ......................................................... 31 Portugal .................................................................... 157 Denmark .................................................................... 36 Romania ................................................................... 160 Estonia ........................................................................ 42 Slovakia ................................................................... -

Quarterly Statement Q1 2021

Quarterly Statement for Q1 2021 Metzingen, May 5, 2021 HUGO BOSS with solid start to the year as business recovery continues • Group sales decline limited to minus 8% in Q1, currency-adjusted • Ongoing strong dynamic in mainland China as sales almost double • Momentum in online business strongly accelerates with sales up 72% • Casualwear sales return to mid-single-digit growth • Positive EBIT of EUR 1 million generated in Q1 “Despite ongoing implications of the pandemic, especially in Europe, we have seen a solid and promising start into the year,” says Yves Müller, Spokesperson of the Managing Board of HUGO BOSS AG. “I am particularly pleased by the further progress along our strategic growth drivers – Online, mainland China and casualwear – which have all seen momentum further accelerating. All this makes us confident for the remainder of the year as we expect both sales and EBIT to recover noticeably in the further course of 2021.” In the first quarter of 2021, HUGO BOSS successfully continued its gradual business recovery, limiting the overall sales decline to 8%, currency-adjusted. In Group currency, sales decreased 10% to EUR 497 million (Q1 2020: EUR 555 million). While the negative implications of the COVID-19 pandemic continued to weigh on key European markets, momentum further accelerated along the Company’s strategic growth drivers – Online, mainland China and casualwear. In addition, sequential improvements in the important U.S. business as well as a robust performance of the Group’s wholesale business contributed positively to the overall sales development in the first quarter. 1 HUGO BOSS AG Dieselstrasse 12 72555 Metzingen Germany Phone +49 7123 94-0 Strong dynamic in mainland China continues The pace and intensity of the Company’s business recovery significantly varied across regions in the reporting period. -

JAZZ ORCHESTRA Christoph Cech Austria 2019

JAZZ ORCHESTRA Christoph Cech Austria 2019 Oct. 16th–19th, 2019 Graz, Vienna, Linz, Salzburg Picture: © Helmut Lackinger © Helmut Picture: JAZZ ORCHESTRA Euroblues – Impressions from Europe Conductor & Composer: Christoph Cech Oct. 16th, 20.00: Graz, University of Music and Performing Arts / WIST Oct. 17th, 19.30: Vienna, Funkhaus / Studio 3 Oct. 18th, 20.00: Linz, Anton Bruckner Private University / Großer Saal second concert: Upper Austrian Jazz Orchestra Oct. 19th, 19.00: Salzburg, Festival »Jazz & The City« / Szene LINE-UP Ajda Stina Turek (Slovenia), voice Lana Janjanin (Croatia), voice Oilly Wallace (Denmark), alto saxophone Sebastian Jonsson (Sweden), alto & soprano saxophone Štěpán Flagar (Czech Republic), tenor saxophone Danielius Pancerovas (Lithuania), baritone saxophone Tim Rabbitt (Great Britain), trumpet & flugelhorn Idar Eliassen Pedersen (Norway), trumpet & flugelhorn Ivan Radivojević (Serbia), trumpet & flugelhorn Aarni Häkkinen (Finland), trombone Janning Trumann (Germany), trombone Cyril Galamini (France), bass trombone Elza Ozolina (Latvia), piano & keyboards Andreas Erd (Austria), electric guitar Heikko-Joseph Remmel (Estonia), electric bass & double bass Daniel Bagutti (Switzerland), drums Christoph Cech (Austria), conductor & composer Since 1965, public radio stations, who are part of the European Broadcasting Union (EBU) have been sending young jazz talents under 30 to the Euroradio Jazz Orchestra every year. In the host ing country, which changes every year, they work with an established professional to de- velop and perform a new original program. In October 2019, the 16 excellent young musicians from just as many countries will be guests in Austria for the fi rst time in decades on the initia- tive of the jazz department of ORF Radio Ö1. We are honoured to engage Christoph Cech, one of the country’s most distinguished jazz orchestra experts, as composer and conductor. -

The National Socialist Revolution That Swept Through Germany in 1933, and It Examines the Choices Individual Germans Were Forced to Confront As a Result

Chapter 5 The National The Scope and Sequence Socialist Individual Choosing to & Society Participate Revolution We & They Judgment, Memory & Legacy The Holocaust Hulton Archive / Stringer / Gey Images / Gey / Stringer Archive Hulton HaHB_chapter5_v1_PPS.indd 220 3/7/17 4:34 PM Overview On January 30, 1933, President Paul von Hindenburg named Adolf Hitler chancellor of Germany. Within days of Hitler’s appointment, the Nazis began to target their political opposition and those they considered enemies of the state, especially Communists and Jews. Within months, they had transformed Germany into a dictatorship. This chapter chronicles the National Socialist revolution that swept through Germany in 1933, and it examines the choices individual Germans were forced to confront as a result. HaHB_chapter5_v1_PPS.indd 221 3/7/17 4:34 PM Chapter 5 Introduction Hitler’s appointment as chancellor on January 30, 1933, thrilled some Ger- Essential mans and horrified others. Writing in 1939, journalist Sebastian Haffner said Questions that when he read the news that afternoon, his reaction was “icy horror”: • What made it possible for Certainly this had been a possibility for a long time. You had to reckon with it. the Nazis to transform Nevertheless it was so bizarre, so incredible, to read it now in black and white. Germany into a dicta- Hitler Reich Chancellor . for a moment I physically sensed the man’s odor of torship during their first blood and filth, the nauseating approach of a man-eating animal—its foul, sharp years in power? claws in my face. • What choices do individ- Then I shook the sensation off, tried to smile, started to consider, and found many uals have in the face of reasons for reassurance. -

GCSE History Exam Questions – Germany

NAME: GCSE History Exam Questions – Germany This booklet contains lots of exam questions for you to practise before your exams. After you have revised a topic, you need to answer some of the questions in this booklet. You can identify the relevant ones as they have been split up by the Key Questions (KQ) on the specification and in the revision guides. You need to make sure you answer the questions in timed conditions (remember 1 mark per minute). You can then check your answers against your notes to see if you got them right. After you have marked some of the questions yourself, you can give them to your teacher to mark. This will help you to see which questions you are better at and which need more practise. It is really important that you complete the essay questions as many times as possible as these are worth the most marks on the exam paper. This approach will help you achieve the best grades possible in the exam. Good luck! Question 1 – Use the source and you own knowledge to describe … (5 marks) You need to identify what you can see in the source. Then link this to what you know about the topic. You need to write 2-3 developed points about the issue in the question. Try and include an example / fact / statistic to show your knowledge. You need to do this in 5 minutes maximum. KQ1 Source A – A map showing Germany after the Treaty of Versailles 1. Use the source and your own knowledge to describe the impact of the Treaty of Versailles on Germany.