(2012) It's All Just a Little Bit of History Repeating Pop Stars, Audiences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Review of Conservatoire and Performing-Arts Provision in Wales

Review of conservatoire and performing-arts provision in Wales Lord Murphy of Torfaen Submitted to the Cabinet Secretary for Education, Welsh Government November 2017 1 FOREWORD To the Cabinet Secretary for Education I am pleased to submit my Review of conservatoire and performing-arts provision in Wales. Task Your predecessor announced on 11 December 2015 that he had asked me to carry out an independent review. His Written Statement, which includes the terms of reference of the review, explained: "The aim of the Review is to ensure that Wales continues to benefit from high quality intensive performing arts courses which focus on practical, vocational performance. Such provision is crucial to the skills' needs of the creative industries and to the cultural life of Wales." The full terms of reference are set out in Appendix 1. I was asked to examine the current arrangements for supporting conservatoire and related provision in higher education in Wales and also to examine the role of the Higher Education Funding Council of Wales (HEFCW) in supporting this provision. I was also asked specifically for recommendations on the future funding of conservatoire and related provision in Wales, and for possible future curriculum developments to be identified. Method A general call was issued on the government website for submissions in response to the terms of reference. In addition, I wrote requesting submissions individually to the organisations most affected by the Review, the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama (RWCMD or the College), the University of South Wales (USW), HEFCW. I also wrote to the other universities in Wales and a range of organisations in the cultural and creative sector, including Arts Council Wales and the National Performing Companies. -

Cardiff Meetings & Conferences Guide

CARDIFF MEETINGS & CONFERENCES GUIDE www.meetincardiff.com WELCOME TO CARDIFF CONTENTS AN ATTRACTIVE CITY, A GREAT VENUE 02 Welcome to Cardiff That’s Cardiff – a city on the move We’ll help you find the right venue and 04 Essential Cardiff and rapidly becoming one of the UK’s we’ll take the hassle out of booking 08 Cardiff - a Top Convention City top destinations for conventions, hotels – all free of charge. All you need Meet in Cardiff conferences, business meetings. The to do is call or email us and one of our 11 city’s success has been recognised by conference organisers will get things 14 Make Your Event Different the British Meetings and Events Industry moving for you. Meanwhile, this guide 16 The Cardiff Collection survey, which shows that Cardiff is will give you a flavour of what’s on offer now the seventh most popular UK in Cardiff, the capital of Wales. 18 Cardiff’s Capital Appeal conference destination. 20 Small, Regular or Large 22 Why Choose Cardiff? 31 Incentives Galore 32 #MCCR 38 Programme Ideas 40 Tourist Information Centre 41 Ideas & Suggestions 43 Cardiff’s A to Z & Cardiff’s Top 10 CF10 T H E S L E A CARDIFF S I S T E N 2018 N E T S 2019 I A S DD E L CAERDY S CARDIFF CAERDYDD | meetincardiff.com | #MeetinCardiff E 4 H ROAD T 4UW RAIL ESSENTIAL INFORMATION AIR CARDIFF – THE CAPITAL OF WALES Aberdeen Location: Currency: E N T S S I E A South East Wales British Pound Sterling L WELCOME! A90 E S CROESO! Population: Phone Code: H 18 348,500 Country code 44, T CR M90 Area code: 029 20 EDINBURGH DF D GLASGOW M8 C D Language: Time Zone: A Y A68 R D M74 A7 English and Welsh Greenwich Mean Time D R I E Newcastle F F • C A (GMT + 1 in summertime) CONTACT US A69 BELFAST Contact: Twinned with: Meet in Cardiff team M6 Nantes – France, Stuttgart – Germany, Xiamen – A1 China, Hordaland – Norway, Lugansk – Ukraine Address: Isle of Man M62 Meet in Cardiff M62 Distance from London: DUBLIN The Courtyard – CY6 LIVERPOOL Approximately 2 hours by road or train. -

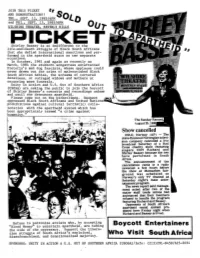

PICKET R, and DEMONSTRATION!! Sol

JOIN THIS PICKET r, AND DEMONSTRATION!! SOl.. THU., SEPT. 12, 1985/6PM 0 and FRI., SEPT. 13, 1985/6PM WILSHIRE THEATER, BEVERLY HILLS 00.,. PICKET Shirley Bassey is so indifferent to the life-and-death struggle of Black South Africans that she defied international sanctions and per formed in the apartheid state on two separate occasions. In October, 1981 and again as recently as March, 1984 the stubborn songstress entertained Pretoria's mad dog fascists, whose applause could never drown out the cries of malnourished Black South African babies, the screams of tortured detainees, or outraged widows and mothers at recurring mass funerals. Unity in Action and U.S. Out of Southern Africa (USOSA) are askin? the public to join the boycott of Shirley Bassey s concerts and recordings unless and until she denounces apartheid. Please come out on the picketlines. Respect oppressed Black South Africans and United Nations prohibitions against cultural (artistic) colla boration with" the apartheid system which has been appropriately termed "a crime against humani " OSLO, Norway (AP) - The state-financed Norwegian televi sion company cancelled a live broadcast Saturday of a Red Cross charity show featuring singers Cliff Richard and Shirley Bassey because the two have performed in South Africa. The annoWlcement of the cancellation came in a radio newscast a few hours before the show at Momarken fair ground was scheduled on Norway's only TV channel as Saturday night's main enter tainment program. The news report said manage ment acted after two of the major staff trade unions had annoWlced that their members refused to handle the prograIll featuring Richard and Bassey. -

Cardiff, Wales – the Places Where We Go Itinerary Day

CARDIFF, WALES – THE PLACES WHERE WE GO ITINERARY DAY ONE: The Heart of Cardiff Explore Cardiff City Center. This will help you get your bearings in the heart of Cardiff. Browse the unique shops within the Victorian Arcades. For modern shopping, you can explore the S t David’s Dewi Sant shopping center. Afternoon: Visit the N ational Museum Cardiff or stroll Cardiff via the Centenary Walk which runs 2.3 miles within Cardiff city center. This path passes through many of Cardiff’s landmarks and historic buildings. DAY TWO – Cardiff Castle and Afternoon Excursion Morning: Visit Cardiff Castle . One of Wales’ leading heritage attractions and a site of international significance. Located in the heart of the capital, Cardiff Castle’s walls and fairytale towers conceal 2,000 years of history. Arrive early and plan on at least 2 hours. Afternoon: Hop on a train to explore a local town – consider Llantwit Major or Penarth. We explored B arry Island, which offers seaside rides, food, and vistas of the Bristol Channel. DAY THREE – Castle Ruins Raglan Castle : Step back in time and explore the ruins of an old castle. Travel by train from Cardiff Central to Newport, where you’ll catch a bus at the Newport Bus Station-Friars Walks (careful to depart from the correct bus station). Have lunch in the town of Raglan at The Ship Inn before travelling back to Cardiff. You might find yourself waiting up to an hour for the bus ride back to the city. If time permits, hop off the bus on the way back to Cardiff to explore the ancient Roman village of Caerloen. -

Holding the BBC to Account for Delivering for Audiences

Holding the BBC to account for delivering for audiences Performance Measures Publication Date: 13 October 2017 Contents Section 1. Procedures and considerations for setting and amending the performance measures 1 2. Performance Measurement Framework 4 Holding the BBC to account for delivering for audiences 1. Procedures and considerations for setting and amending the performance measures Introduction 1.1 Under the Royal Charter1 and the agreement between the Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport, and the BBC (the “Agreement”) published by Government on 15 December 2016, Ofcom may determine measures (further to those determined by the BBC) that Ofcom considers appropriate to assess the BBC’s success in fulfilling the Mission and promoting the Public Purposes2 as set out in the Royal Charter3 and the agreement between the Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport, and the BBC (the “Agreement”) published by Government on 15 December 2016.4 1.2 This document forms part of the BBC’s Operating Framework. It sets out how Ofcom will set and amend performance measures and the procedures to be followed.5 How Ofcom will set and amend performance measures 1.3 When setting and amending performance measures, Ofcom will apply the relevant legal framework. 1.4 Ofcom is a statutory corporation created by the Office of Communications Act 2002. 1.5 Ofcom’s power to regulate the BBC is derived from the Communications Act 2003, which sets out that for the purposes of the carrying out regulation of the BBC we will have such powers and duties -

Performing Borders

Radical Musicology Volume 1 (2006) ISSN 1751-7788 Beyond Borders: The Female Welsh Pop Voice Sarah Hill University of Southampton For all its reputation as a musical culture, the number of women pop stars to 1 have emerged from Wales can be counted charitably on two hands, with some fingers to spare. Wales is a small country, host to two rich linguistic cultures, each with its own musical heritage and traditions, yet very few musicians of either gender have crossed over from one tradition to the other. The rarity of a female singer making such a border crossing is marked, allowing for a delicate lineage to be traced across the decades, from the 1960s to the present, revealing certain commonalities of experience, acceptance, and reversion. With this in mind, I would like to draw a linguistic and cultural connection between two determinedly different Welsh women singers. In the 1960s, when women’s voices were the mainstays of Motown, the folk circuit and the Haight-Ashbury, in Wales only Mary Hopkin managed to shift from Welsh-language to Anglo-American pop; thirty years later, Cerys Matthews made the same journey. These two women bear certain similarities: they both come from South Wales, they are both singers whose first, or preferred, language is Welsh, and they both found their niche in the Anglo-American mainstream market. These two women faced the larger cultural problems of linguistic and musical border-crossings, but more importantly, they challenged the place of the female pop voice in Wales, and of the female Welsh pop voice in Anglo-America. -

The Live Album Or Many Ways of Representing Performance

Sergio Mazzanti The live album or many ways of representing ... DOI: 10.2298/MUZ1417069M UDK: 78.067.26 The Live Album or Many Ways of Representing Performance Sergio Mazzanti1 University of Macerata (Macerata) Abstract The analysis of live albums can clarify the dialectic between studio recordings and live performances. After discussing key concepts such as authenticity, space, time and place, and documentation, the author gives a preliminary definition of live al- bums, combining available descriptions and comparing them with different typolo- gies and functions of these recordings. The article aims to give a new definition of the concept of live albums, gathering their primary elements: “A live album is an officially released extended recording of popular music representing one or more actually occurred public performances”. Keywords performance, rock music, live album, authenticity Introduction: recording and performance The relationship between recordings and performances is a central concept in performance studies. This topic is particularly meaningful in popular music and even more so in rock music, where the dialectic between studio recordings and live music is crucial for both artists and the audience. The cultural implications of this jux- taposition can be traced through the study of ‘live albums’, both in terms of recordings and the actual live experience. In academic stud- ies there is a large amount of literature on the relationship between recording and performance, but few researchers have paid attention to this particular -

WDAM Radio's History of the Animals

Listener’s Guide To “WDAM Radio’s History Of James Bond” You have security clearance to enjoy “WDAM Radio’s History Of James Bond.” Classified – until now, this is the most comprehensive top secret dossier of ditties from James Bond television and film productions ever assembled. WDAM Radio’s undercover record researchers have uncovered all the opening title themes, as well as “secondary songs” and various end title themes worth having. Our secret musicology agents also have gathered intelligence on virtually every known and verifiable* song that was submitted to and rejected by the various James Bond movie producers as proposed theme music. All of us at the station hope you will enjoy this musical license to thrill.** Rock on. Radio Dave *There is a significant amount of dubious data on Wikipedia and YouTube with respect to songs that were proposed, but not accepted, for various James Bond films. Using proprietary alga rhythms (a/k/a Radio Dave’s memory and WDAM Radio’s Groove Yard archives), as well as identifying obvious inconsistencies on several postings purporting to present such claims, we have revoked the license of such songs to be included in this collection. (For instance, two sites claim Elvis Presley songs that were included in two of his movies were originally proposed to the James Bond producers – not true.) **Watch for updates to this dossier as future James Bond films are issued, as well as additional “rejected songs” to existing films are identified and obtained via our ongoing overt and covert musicology surveillance activities. WDAM Radio's History Of James Bond # Film/Title (+ Year) Artist & (Composer) James Bond Chart Comments Position/ Year* 01 Casino Royale (1954) Barry Nelson 1954 Episode of Climax! Mystery Theater broadcast live on 10/21/1954 starring Barry Nelson. -

St David's Welsh Quiz

St David's Welsh Quiz 1 What is the Welsh name for St David? St Dewi 2 Where was Prince Charles invested as Prince of Wales? Caernarfon What was the name of the island on which the Americans dropped a hydrogen bomb on St Bikini Atoll 3 David's Day 1954? 4 In which year was the university of Wales founded: 1873, 1883, 1893 or 1903? 1893 5 Which flower is the emblem for Wales? Daffodil 6 What is the Welsh for Wales? Cymru 7 Which place in Wales was the setting for the TV series 'The Prisoner'? Port Merrion 8 In which city was Welsh songstress Shirley Bassey born? Cardiff 9 Which part of Wales did the Romans call Mona? Anglesey 10 Name the Welsh soldier who became famous after being badly burned in the Falklands war. Simon Weston 11 What three colours are used on the Welsh flag? Green, White & Red Born in Tonypandy on St David's Day who was the boxer who took Joe Louis the distance for Tommy Farr 12 his world crown? 13 Welshman Richard Jenkins was the real name of which famous actor? Richard Burton 14 What is the name of the small Welsh boat made of skins stretched over a frame? Coracle 15 What is the name of the annual festivals held to encourage the fine arts? Eisteddfod 16 What would your star sign be if you were born on St David's Day? Pisces 17 What is the sea weather area that lies to the south of Wales? Lundy 18 Which vegetable is an emblem of Wales? Leek 19 What is the name of the stretch of water which separates Anglesey from mainland Wales? Menai Strait 20 Which Welshman had a monster hit with the song 'Green Green Grass of Home'? -

SHSU Video Archive Basic Inventory List Department of Library Science

SHSU Video Archive Basic Inventory List Department of Library Science A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume One – Hitmakers: The Teens Who Stole Pop Music. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume One – Dionne Warwick: Don’t Make Me Over. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume Two – Bobby Darin. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume Two – [1] Leiber & Stoller; [2] Burt Bacharach. c2001. A & E Top 10. Show #109 – Fads, with commercial blacks. Broadcast 11/18/99. (Weller Grossman Productions) A & E, USA, Channel 13-Houston Segments. Sally Cruikshank cartoon, Jukeboxes, Popular Culture Collection – Jesse Jones Library Abbott & Costello In Hollywood. c1945. ABC News Nightline: John Lennon Murdered; Tuesday, December 9, 1980. (MPI Home Video) ABC News Nightline: Porn Rock; September 14, 1985. Interview with Frank Zappa and Donny Osmond. Abe Lincoln In Illinois. 1939. Raymond Massey, Gene Lockhart, Ruth Gordon. John Ford, director. (Nostalgia Merchant) The Abominable Dr. Phibes. 1971. Vincent Price, Joseph Cotton. Above The Rim. 1994. Duane Martin, Tupac Shakur, Leon. (New Line) Abraham Lincoln. 1930. Walter Huston, Una Merkel. D.W. Griffith, director. (KVC Entertaiment) Absolute Power. 1996. Clint Eastwood, Gene Hackman, Laura Linney. (Castle Rock Entertainment) The Abyss, Part 1 [Wide Screen Edition]. 1989. Ed Harris. (20th Century Fox) The Abyss, Part 2 [Wide Screen Edition]. 1989. Ed Harris. (20th Century Fox) The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: [1] documentary; [2] scripts. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: scripts; special materials. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: special features – I. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: special features – II. Academy Award Winners: Animated Short Films. -

Keyfinder V2 Dataset © Ibrahim Sha'ath 2014

KeyFinder v2 dataset © Ibrahim Sha'ath 2014 ARTIST TITLE KEY 10CC Dreadlock Holiday Gm 187 Lockdown Gunman (Natural Born Chillers Remix) Ebm 4hero Star Chasers (Masters At Work Main Mix) Am 50 Cent In Da Club C#m 808 State Pacifc State Ebm A Guy Called Gerald Voodoo Ray A A Tribe Called Quest Can I Kick It? (Boilerhouse Mix) Em A Tribe Called Quest Find A Way Ebm A Tribe Called Quest Vivrant Thing (feat Violator) Bbm A-Skillz Drop The Funk Em Aaliyah Are You That Somebody? Dm AC-DC Back In Black Em AC-DC You Shook Me All Night Long G Acid District Keep On Searching G#m Adam F Aromatherapy (Edit) Am Adam F Circles (Album Edit) Dm Adam F Dirty Harry's Revenge (feat Beenie Man and Siamese) G#m Adam F Metropolis Fm Adam F Smash Sumthin (feat Redman) Cm Adam F Stand Clear (feat M.O.P.) (Origin Unknown Remix) F#m Adam F Where's My (feat Lil' Mo) Fm Adam K & Soha Question Gm Adamski Killer (feat Seal) Bbm Adana Twins Anymore (Manik Remix) Ebm Afrika Bambaataa Mind Control (The Danmass Instrumental) Ebm Agent Sumo Mayhem Fm Air Sexy Boy Dm Aktarv8r Afterwrath Am Aktarv8r Shinkirou A Alexis Raphael Kitchens & Bedrooms Fm Algol Callisto's Warm Oceans Am Alison Limerick Where Love Lives (Original 7" Radio Edit) Em Alix Perez Forsaken (feat Peven Everett and Spectrasoul) Cm Alphabet Pony Atoms Em Alphabet Pony Clones Am Alter Ego Rocker Am Althea & Donna Uptown Top Ranking (2001 digital remaster) Am Alton Ellis Black Man's Pride F Aluna George Your Drums, Your Love (Duke Dumont Remix) G# Amerie 1 Thing Ebm Amira My Desire (Dreem Teem Remix) Fm Amirali -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms International A Beil & Howell Information Company 300 Nortfi Z eeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106 -1 3 4 6 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9218977 Shirley Caesar: A woman of words Harrington, Brooksie Eugene, Ph D. The Ohio State University, 1992 UMI 300 N.