A Guide to Reading Three Kingdoms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classlists for C by Group

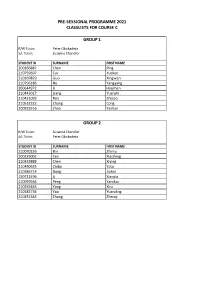

PRE-SESSIONAL PROGRAMME 2021 CLASSLISTS FOR COURSE C GROUP 1 R/W Tutor: Peter Obukadeta S/L Tutor: Suzanne Chandler STUDENT ID SURNAME FIRST NAME 200166887 Chen Ping 210759697 Cui Yuekun 210169829 Guo Xingwen 210796186 Hu Yangyang 200644972 Li Haozhan 210443017 Liang Yuanzhi 210421093 Ren Zhijiao 210532322 Zhang Cong 200925516 Zhao Yashan GROUP 2 R/W Tutor: Suzanne Chandler S/L Tutor: Peter Obukadeta STUDENT ID SURNAME FIRST NAME 210070226 Bin Zhimu 200329002 Cen Xiaofeng 210333888 Chen Xiying 210450635 Chiba Yota 210386714 Dong Jiahui 190711496 Li Xiaoxia 210059564 Peng Yanduo 210255465 Yang Xiru 210182736 Yao Yuanding 210252383 Zhang Zhenqi GROUP 3 R/W Tutor: Mark Heffernan S/L Tutor: Alan Hart STUDENT ID SURNAME FIRST NAME 210154386 Cai Zhenping 210462580 Ge Xiaodan 210648276 Hirunkhajonrote Kullanut 210182714 Huang Siwei 200141563 Kung Tzu-Ning 200305176 Punsri Punnatorn 200664774 Sayin Humeyra 210186446 Shehata Omar 171003323 Tutberidze Tea 200134624 Wang Shuo 200136019 Xu Ming 200278696 Yan Jiaxin 210357851 Yuan Lai 210029165 Zhang Anru 210219777 Zhang Jiasheng GROUP 4 R/W Tutor: Sherin White S/L Tutor: Alan Hart STUDENT ID SURNAME FIRST NAME 200247588 Chen Chong 200349343 Li Cheng 210622933 Liang Wenxuan 210219618 Liu Huiyuan 210376298 Liu Zeyu 210237531 Mei Lyuke 200132620 Qi Shuyu 210681907 Wang Handuo 200015356 Wu Zhuoyue 200071994 Xie Kaijun GROUP 5 R/W Tutor: Chukwudi Dozie S/L Tutor: Nora Mikso STUDENT ID SURNAME FIRST NAME 210563304 Almalek Ahmed 210186309 Altamimi Saud 210251102 Cheng Han-Yu 210349823 Guo Wenyuan 210239409 -

Great Food, Great Stories from Korea

GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIE FOOD, GREAT GREAT A Tableau of a Diamond Wedding Anniversary GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS This is a picture of an older couple from the 18th century repeating their wedding ceremony in celebration of their 60th anniversary. REGISTRATION NUMBER This painting vividly depicts a tableau in which their children offer up 11-1541000-001295-01 a cup of drink, wishing them health and longevity. The authorship of the painting is unknown, and the painting is currently housed in the National Museum of Korea. Designed to help foreigners understand Korean cuisine more easily and with greater accuracy, our <Korean Menu Guide> contains information on 154 Korean dishes in 10 languages. S <Korean Restaurant Guide 2011-Tokyo> introduces 34 excellent F Korean restaurants in the Greater Tokyo Area. ROM KOREA GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIES FROM KOREA The Korean Food Foundation is a specialized GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIES private organization that searches for new This book tells the many stories of Korean food, the rich flavors that have evolved generation dishes and conducts research on Korean cuisine after generation, meal after meal, for over several millennia on the Korean peninsula. in order to introduce Korean food and culinary A single dish usually leads to the creation of another through the expansion of time and space, FROM KOREA culture to the world, and support related making it impossible to count the exact number of dishes in the Korean cuisine. So, for this content development and marketing. <Korean Restaurant Guide 2011-Western Europe> (5 volumes in total) book, we have only included a selection of a hundred or so of the most representative. -

French Names Noeline Bridge

names collated:Chinese personal names and 100 surnames.qxd 29/09/2006 13:00 Page 8 The hundred surnames Pinyin Hanzi (simplified) Wade Giles Other forms Well-known names Pinyin Hanzi (simplified) Wade Giles Other forms Well-known names Zang Tsang Zang Lin Zhu Chu Gee Zhu Yuanzhang, Zhu Xi Zeng Tseng Tsang, Zeng Cai, Zeng Gong Zhu Chu Zhu Danian Dong, Zhu Chu Zhu Zhishan, Zhu Weihao Jeng Zhu Chu Zhu jin, Zhu Sheng Zha Cha Zha Yihuang, Zhuang Chuang Zhuang Zhou, Zhuang Zi Zha Shenxing Zhuansun Chuansun Zhuansun Shi Zhai Chai Zhai Jin, Zhai Shan Zhuge Chuko Zhuge Liang, Zhan Chan Zhan Ruoshui Zhuge Kongming Zhan Chan Chaim Zhan Xiyuan Zhuo Cho Zhuo Mao Zhang Chang Zhang Yuxi Zi Tzu Zi Rudao Zhang Chang Cheung, Zhang Heng, Ziche Tzuch’e Ziche Zhongxing Chiang Zhang Chunqiao Zong Tsung Tsung, Zong Xihua, Zhang Chang Zhang Shengyi, Dung Zong Yuanding Zhang Xuecheng Zongzheng Tsungcheng Zongzheng Zhensun Zhangsun Changsun Zhangsun Wuji Zou Tsou Zou Yang, Zou Liang, Zhao Chao Chew, Zhao Kuangyin, Zou Yan Chieu, Zhao Mingcheng Zu Tsu Zu Chongzhi Chiu Zuo Tso Zuo Si Zhen Chen Zhen Hui, Zhen Yong Zuoqiu Tsoch’iu Zuoqiu Ming Zheng Cheng Cheng, Zheng Qiao, Zheng He, Chung Zheng Banqiao The hundred surnames is one of the most popular reference Zhi Chih Zhi Dake, Zhi Shucai sources for the Han surnames. It was originally compiled by an Zhong Chung Zhong Heqing unknown author in the 10th century and later recompiled many Zhong Chung Zhong Shensi times. The current widely used version includes 503 surnames. Zhong Chung Zhong Sicheng, Zhong Xing The Pinyin index of the 503 Chinese surnames provides an access Zhongli Chungli Zhongli Zi to this great work for Western people. -

Engaging with the Trans-East Asian Cultural Tradition in Modern Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Taiwanese Literatures, 1880S-1940S

Afterlives of the Culture: Engaging with the Trans-East Asian Cultural Tradition in Modern Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Taiwanese Literatures, 1880s-1940s The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Hashimoto, Satoru. 2014. Afterlives of the Culture: Engaging with the Trans-East Asian Cultural Tradition in Modern Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Taiwanese Literatures, 1880s-1940s. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:13064962 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Afterlives of the Culture: Engaging with the Trans-East Asian Cultural Tradition in Modern Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Taiwanese Literatures, 1880s-1940s A dissertation presented by Satoru Hashimoto to The Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of East Asian Languages and Civilizations Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts August 2014 ! ! © 2014 Satoru Hashimoto All rights reserved. ! ! Dissertation Advisor: Professor David Der-Wei Wang Satoru Hashimoto Afterlives of the Culture: Engaging with the Trans-East Asian Cultural Tradition in Modern Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Taiwanese Literatures, 1880s-1940s Abstract This dissertation examines how modern literature in China, Japan, Korea, and Taiwan in the late-nineteenth to the early-twentieth centuries was practiced within contexts of these countries’ deeply interrelated literary traditions. -

The Romance of the Three Kingdoms Podcast. This Is Episode 48. Last

Welcome to the Romance of the Three Kingdoms Podcast. This is episode 48. Last time, Sun Quan and the troops of the Southlands had just defeated and killed Huang (2) Zu (3), a close friend and top commander of Liu Biao, the imperial protector of Jing (1) Province. Sun Quan had also captured the key city of Jiangxia (1,4), which Huang Zu was defending. Upon receiving Huang Zu’s head, Sun Quan ordered that it be placed in a wooden box and taken back to the Southlands to be placed as an offering at the altar of his father, who had been killed in battle against Liu Biao years earlier. He then rewarded his troops handsomely, promoted Gan Ning, the man who defected from Huang Zu and then killed him in battle, to district commander, and began discussion of whether to leave troops to garrison the newly conquered city. His adviser Zhang Zhao (1), however, said, “A lone city so far from our territory is impossible to hold. We should return to the Southlands. When Liu Biao finds out we have killed Huang Zu, he will surely come looking for revenge. We should rest our troops while he overextends his. This will guarantee victory. We can then attack him as he falls back and take Jing Province.” Sun Quan took this advice and abandoned his new conquest and returned home. But there was still the matter of Su (1) Fei (1), the enemy general he had captured. This Su Fei was friends with Gan Ning and was actually the one who helped him defect to Sun Quan. -

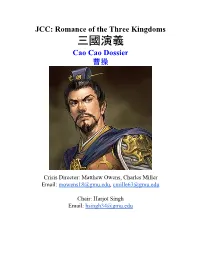

Cao Pi (Pages 5-6) 5

JCC: Romance of the Three Kingdoms 三國演義 Cao Cao Dossier 曹操 Crisis Director: Matthew Owens, Charles Miller Email: [email protected], [email protected] Chair: Harjot Singh Email: [email protected] Table of Contents: 1. Front Page (Page 1) 2. Table of Contents (Page 2) 3. Introduction to the Cao Cao Dossier (Pages 3-4) 4. Cao Pi (Pages 5-6) 5. Cao Zhang (Pages 7-8) 6. Cao Zhi (Pages 9-10) 7. Lady Bian (Page 11) 8. Emperor Xian of Han (Pages 12-13) 9. Empress Fu Shou (Pages 14-15) 10. Cao Ren (Pages 16-17) 11. Cao Hong (Pages 18-19) 12. Xun Yu (Pages 20-21) 13. Sima Yi (Pages 22-23) 14. Zhang Liao (Pages 24-25) 15. Xiahou Yuan (Pages 26-27) 16. Xiahou Dun (Pages 28-29) 17. Yue Jin (Pages 30-31) 18. Dong Zhao (Pages 32-33) 19. Xu Huang (Pages 34-35) 20. Cheng Yu (Pages 36-37) 21. Cai Yan (Page 38) 22. Han Ji (Pages 39-40) 23. Su Ze (Pages 41-42) 24. Works Cited (Pages 43-) Introduction to the Cao Cao Dossier: Most characters within the Court of Cao Cao are either generals, strategists, administrators, or family members. ● Generals lead troops on the battlefield by both developing successful battlefield tactics and using their martial prowess with skills including swordsmanship and archery to duel opposing generals and officers in single combat. They also manage their armies- comprising of troops infantrymen who fight on foot, cavalrymen who fight on horseback, charioteers who fight using horse-drawn chariots, artillerymen who use long-ranged artillery, and sailors and marines who fight using wooden ships- through actions such as recruitment, collection of food and supplies, and training exercises to ensure that their soldiers are well-trained, well-fed, well-armed, and well-supplied. -

Official Colours of Chinese Regimes: a Panchronic Philological Study with Historical Accounts of China

TRAMES, 2012, 16(66/61), 3, 237–285 OFFICIAL COLOURS OF CHINESE REGIMES: A PANCHRONIC PHILOLOGICAL STUDY WITH HISTORICAL ACCOUNTS OF CHINA Jingyi Gao Institute of the Estonian Language, University of Tartu, and Tallinn University Abstract. The paper reports a panchronic philological study on the official colours of Chinese regimes. The historical accounts of the Chinese regimes are introduced. The official colours are summarised with philological references of archaic texts. Remarkably, it has been suggested that the official colours of the most ancient regimes should be the three primitive colours: (1) white-yellow, (2) black-grue yellow, and (3) red-yellow, instead of the simple colours. There were inconsistent historical records on the official colours of the most ancient regimes because the composite colour categories had been split. It has solved the historical problem with the linguistic theory of composite colour categories. Besides, it is concluded how the official colours were determined: At first, the official colour might be naturally determined according to the substance of the ruling population. There might be three groups of people in the Far East. (1) The developed hunter gatherers with livestock preferred the white-yellow colour of milk. (2) The farmers preferred the red-yellow colour of sun and fire. (3) The herders preferred the black-grue-yellow colour of water bodies. Later, after the Han-Chinese consolidation, the official colour could be politically determined according to the main property of the five elements in Sino-metaphysics. The red colour has been predominate in China for many reasons. Keywords: colour symbolism, official colours, national colours, five elements, philology, Chinese history, Chinese language, etymology, basic colour terms DOI: 10.3176/tr.2012.3.03 1. -

The Romance of the Three Kingdoms Podcast. This Is Episode 52

Welcome to the Romance of the Three Kingdoms Podcast. This is episode 52. Previously, we left off with one of the most memorable sequences in the novel, in which Zhao Yun rescued Liu Bei’s infant son, A Dou (1,3), and fought his way through swarms of Cao Cao’s troops to escape. But no sooner had he left the bulk of Cao Cao’s army behind did he run into two more detachments of enemy soldiers, led by two lieutenants under the command of Cao Cao’s general Xiahou Dun. These two guys were brothers. One wielded a battle axe, while the other used a halberd, and they were shouting for Zhao Yun to surrender. Zhao Yun, of course, paid no heed to their words and greeted them with his spear. Within three bouts, the elder brother, the axe-wielder, was stabbed off his horse. Zhao Yun took the opening and ran. The younger brother, however, gave chase. As he closed in, the tip of his halberd flashed around Zhao Yun’s back. But Zhao Yun suddenly turned around, and the two were face to face right next to each other. Wielding his spear in his left hand, Zhao Yun blocked the halberd. At the same time, his right hand pulled out the prized sword that he had taken from Cao Cao’s sword-bearer earlier in the day. Where the sword landed, half of his opponent’s head and helmet went flying off. Seeing their leaders killed, the enemy soldiers scattered, and Zhao Yun once again fled toward Changban (2,3) Bridge. -

三國演義 Court of Liu Bei 劉備法院

JCC: Romance of the Three Kingdoms 三國演義 Court of Liu Bei 劉備法院 Crisis Directors: Matthew Owens, Charles Miller Emails: [email protected], [email protected] Chair: Isis Mosqueda Email: [email protected] Single-Delegate: Maximum 20 Positions Table of Contents: 1. Title Page (Page 1) 2. Table of Contents (Page 2) 3. Chair Introduction Page (Page 3) 4. Crisis Director Introduction Pages (Pages 4-5) 5. Intro to JCC: Romance of the Three Kingdoms (Pages 6-9) 6. Intro to Liu Bei (Pages 10-11) 7. Topic History: Jing Province (Pages 12-14) 8. Perspective (Pages 15-16) 9. Current Situation (Pages 17-19) 10. Maps of the Middle Kingdom / China (Pages 20-21) 11. Liu Bei’s Domain Statistics (Page 22) 12. Guiding Questions (Pages 22-23) 13. Resources for Further Research (Page 23) 14. Works Cited (Pages 24-) Dear delegates, I am honored to welcome you all to the Twenty Ninth Mid-Atlantic Simulation of the United Nations Conference, and I am pleased to welcome you to JCC: Romance of the Three Kingdoms. Everyone at MASUN XXIX have been working hard to ensure that this committee and this conference will be successful for you, and we will continue to do so all weekend. My name is Isis Mosqueda and I am recent George Mason Alumna. I am also a former GMU Model United Nations president, treasurer and member, as well as a former MASUN Director General. I graduated last May with a B.A. in Government and International politics with a minor in Legal Studies. I am currently an academic intern for the Smithsonian Institution, working for the National Air and Space Museum’s Education Department, and a substitute teacher for Loudoun County Public Schools. -

The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Wai Kit Wicky Tse University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Tse, Wai Kit Wicky, "Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier" (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 589. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Abstract As a frontier region of the Qin-Han (221BCE-220CE) empire, the northwest was a new territory to the Chinese realm. Until the Later Han (25-220CE) times, some portions of the northwestern region had only been part of imperial soil for one hundred years. Its coalescence into the Chinese empire was a product of long-term expansion and conquest, which arguably defined the egionr 's military nature. Furthermore, in the harsh natural environment of the region, only tough people could survive, and unsurprisingly, the region fostered vigorous warriors. Mixed culture and multi-ethnicity featured prominently in this highly militarized frontier society, which contrasted sharply with the imperial center that promoted unified cultural values and stood in the way of a greater degree of transregional integration. As this project shows, it was the northwesterners who went through a process of political peripheralization during the Later Han times played a harbinger role of the disintegration of the empire and eventually led to the breakdown of the early imperial system in Chinese history. -

Resaerch on the Creation and Booming of Bird Fu in the Han Dynasty

2021 4th International Conference on Arts, Linguistics, Literature and Humanities (ICALLH 2021) Resaerch on the Creation and Booming of Bird Fu in the Han Dynasty Qunyi Ma ,Shinian Ma* Northwest Normal University, Lanzhou, Gansu, 730070, China *corresponding author:Shinian Ma Keywords: Poems on birds in the han dynasty, General situation of creation, Reasons for rise, Ideological connotation Abstract: The literature with birds as the subject has gone through the profound literary accumulation in the pre-Qin period. In the Han Dynasty, the subject of birds and the Han Fu achieved a perfect combination, forming a unique style of the Han Fu. This unique style is manifested in profound cultural accumulation, profound ideological connotation and distinctive artistic achievements. Bird Fu can be greatly developed in the Han Dynasty. On the one hand, it is related to the prosperity of Fu style literature. On the other hand, the unified and stable social environment of the Han Dynasty, the preference of the rulers for Fu, the frequent banquet activities and the interaction between writers Influence has a very important driving effect. The bird poetry of the Han Dynasty showed rich ideological connotation through the ways of embedding Taoism into things, borrowing things to chanting virtue, and entrusting things to express their will. 1. Introduction As early as the “Book of Songs” in the pre-Qin Dynasty, “birds” have entered literary works as a literary image. By the time of the Han Dynasty, the subject of birds had already entered the vision of fu masters, for example, when Jia Yi lived in Changsha, Wang Taifu wrote “Fu on the Birds. -

THE LAST YEARS 218–220 Liu Bei in Hanzhong 218–219 Guan Yu and Lü Meng 219 Posthumous Emperor 220 the Later History Of

CHAPTER TEN THE LAST YEARS 218–220 Liu Bei in Hanzhong 218–219 Guan Yu and Lü Meng 219 Posthumous emperor 220 The later history of Cao Wei Chronology 218–2201 218 spring: short-lived rebellion at Xu city Liu Bei sends an army into Hanzhong; driven back by Cao Hong summer: Wuhuan rebellion put down by Cao Cao’s son Zhang; Kebineng of the Xianbi surrenders winter: rebellion in Nanyang 219 spring: Nanyang rebellion put down by Cao Ren Liu Bei defeats Xiahou Yuan at Dingjun Mountain summer: Cao Cao withdraws from Hanzhong; Liu Bei presses east down the Han autumn: Liu Bei proclaims himself King of Hanzhong; Guan Yu attacks north in Jing province, besieges Cao Ren in Fan city rebellion of Wei Feng at Ye city winter: Guan Yu defeated at Fan; Lü Meng seizes Jing province for Sun Quan and destroys Guan Yu 220 spring [15 March]: Cao Cao dies at Luoyang; Cao Pi succeeds him as King of Wei winter [11 December]: Cao Pi takes the imperial title; Cao Cao is given posthumous honour as Martial Emperor of Wei [Wei Wudi] * * * * * 1 The major source for Cao Cao’s activities from 218 to 220 is SGZ 1:50–53. They are presented in chronicle order by ZZTJ 68:2154–74 and 69:2175; deC, Establish Peace, 508–560. 424 chapter ten Chronology from 220 222 Lu Xun defeats the revenge attack of Liu Bei against Sun Quan 226 death of Cao Pi, succeeded by his son Cao Rui 238 death of Cao Rui, succeeded by Cao Fang under the regency of Cao Shuang 249 Sima Yi destroys Cao Shuang and seizes power in the state of Wei for his family 254 Sima Shi deposes Cao Fang, replacing him with Cao Mao 255 Sima Shi succeeded by Sima Zhao 260 Cao Mao killed in a coup d’état; replaced by Cao Huan 264 conquest of Shu-Han 266 Sima Yan takes title as Emperor of Jin 280 conquest of Wu by Jin Liu Bei in Hanzhong 218–219 Even while Cao Cao steadily developed his position with honours, titles and insignia, he continued to proclaim his loyalty to Han and to represent himself as a servant—albeit a most successful and distin- guished one—of the established dynasty.