Eva Perón and the Containment of Post-War New

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beneath the Surface: Argentine-United States Relations As Perón Assumed the Presidency

Beneath the Surface: Argentine-United States Relations as Perón Assumed the Presidency Vivian Reed June 5, 2009 HST 600 Latin American Seminar Dr. John Rector 1 Juan Domingo Perón was elected President of Argentina on February 24, 1946,1 just as the world was beginning to recover from World War II and experiencing the first traces of the Cold War. The relationship between Argentina and the United States was both strained and uncertain at this time. The newly elected Perón and his controversial wife, Eva, represented Argentina. The United States’ presence in Argentina for the preceding year was primarily presented through Ambassador Spruille Braden.2 These men had vastly differing perspectives and visions for Argentina. The contest between them was indicative of the relationship between the two nations. Beneath the public and well-documented contest between Perón and United States under the leadership of Braden and his successors, there was another player whose presence was almost unnoticed. The impact of this player was subtlety effective in normalizing relations between Argentina and the United States. The player in question was former United States President Herbert Hoover, who paid a visit to Argentina and Perón in June of 1946. This paper will attempt to describe the nature of Argentine-United States relations in mid-1946. Hoover’s mission and insights will be examined. In addition, the impact of his visit will be assessed in light of unfolding events and the subsequent historiography. The most interesting aspect of the historiography is the marked absence of this episode in studies of Perón and Argentina3 even though it involved a former United States President and the relations with 1 Alexander, 53. -

Krt Madonna Knight Ridder/Tribune

FOLIO LINE FOLIO LINE FOLIO LINE “Music” “Ray of Light” “Something to Remember” “Bedtime Stories” “Erotica” “The Immaculate “I’m Breathless” “Like a Prayer” “You Can Dance” (2000; Maverick) (1998; Maverick) (1995; Maverick) (1994; Maverick) (1992; Maverick) Collection”(1990; Sire) (1990; Sire) (1989; Sire) (1987; Sire) BY CHUCK MYERS Knight Ridder/Tribune Information Services hether a virgin, vamp or techno wrangler, Madon- na has mastered the public- image makeover. With a keen sense of what will sell, she reinvents herself Who’s That Girl? and transforms her music in Madonna Louise Veronica Ciccone was ways that mystify critics and generate fan interest. born on Aug. 16, 1958, in Bay City, Mich. Madonna staked her claim to the public eye by challenging social norms. Her public persona has Oh Father evolved over the years, from campy vixen to full- Madonna’s father, Sylvio, was a design en- figured screen siren to platinum bombshell to gineer for Chrysler/General Dynamics. Her leather-clad femme fatale. Crucifixes, outerwear mother, Madonna, died of breast cancer in undies and erotic fetishes punctuated her act and 1963. Her father later married Joan Gustafson, riled critics. a woman who had worked as the Ciccone Part of Madonna’s secret to success has been family housekeeper. her ability to ride the music video train to stardom. The onetime self-professed “Boy Toy” burst onto I’ve Learned My Lesson Well the pop music scene with a string of successful Madonna was an honor roll student at music video hits on MTV during the 1980s. With Adams High School in Rochester, Mich. -

219 Indexes Reviewed

INDEXES REVIEWED edited by Christine Shuttleworth These extracts from reviews do not pretend to represent a Cambridge University Press: The history of the English organ, complete survey of all reviews in journals and newspapers. We by Stephen Bicknell (£45). Rev. by Felix Aprahamian, Church offer only a selection from quotations that members have sent in. Times, 15Nov 1996. Our reproduction of comments is not a stamp of approval from 'It is unlikely that a finer book on this subject could yet be written the Society of Indexers upon the reviewer's assessment of an in our century... Before the well-organised index, a select index. bibliography lists all the titles to be found in the most comprehensive library relating to the subject.' Extracts are arranged alphabetically under the names of publishers, within the sections: Indexes praised: Two cheers! Chatham Publishing: Building a working model warship: HMS Indexes censured; Indexes omitted; Obiter dicta. Warrior I860, by William Mowll (1997,200 pp, £20). Rev. in Model Boats, 47 (558). Indexes praised 'There is a bibliography, further reading list... plus a useful index.' [Index by SI member Stephanie Rudgard-Redsell] Aldwych Press: Dictionary of Irish literature (2nd edn), ed. by De Agostini Editions: The atlas of literature, ed. by Malcolm Robert Hogan (2 vols, 1,413 pp, £99.50). Rev. by Patrick Bradbury (£25). Rev. by John Naughton, The Times, 21 Sept Crotty, Times Literary Supplement, 30 May 1997. 1996. 'In addition to hundreds of dictionary entries, Hogan presides a '... the book is -

Eva Perón: El Poder Del Deseo

Nuevo Itinerario Revista Digital de Filosofía ISSN 1850-3578 2015 – Vol. 10 – Número X – Resistencia, Chaco, Argentina Eva Perón: el poder del deseo Teresa Rinaldi College of Arts and Sciences National University, San Diego (USA) [email protected] Recibido: 10/06/2015 Aceptado: 22/08/2015 Resumen: El estudio del cuerpo y en sus diversas formas y contextos debe abordarse desde una perspertiva interdisiplinaria que incluye desde el arte y la literatura hasta la medicina y las artes plásticas en búsqueda constante de la significación social del mismo. María Eva Duarte de Perón (1919-1952) fue el centro de una serie de eventos que no solo cambiaron el rumbo de su vida sino también el del mundo político y social de Argentina. Su vida se llama a la observación, el análisis y la búsqueda de respuestas a cómo una simple e ilegítima niña logró llegar a las más altas cumbres de la sociedad argentina. La capacidad de Eva para adaptarse y sobrepasar contratiempos conjuntamente con su estilo único y astucia la catapultaron al estrellato marcando la memoria del pueblo argentino y la comunidad internacional. Dentro de vasto material literario y artístico sobre la vida y obra de Eva, se pueden mencionar: Eva Perón (1970) de Otelo Borroni y Roberto Vacca, La pasión según Eva (1994) de Abel Posse, Eva Perón, the bibliography (1995) de Alicia Dujovne Ortíz, El misterio de Eva Perón (1988,documental) de Tulio Demicheli, Evita Pre-Madonna (1995, documental) de Claudia Nie, Santa Evita (1995) de Tomás Eloy Martínez, Evita (1996, film) de Alan Parker y Evita: Santa o Demonio (1996, film) de Juan Carlos de Sanzo. -

Paraguay's Archive of Terror: International Cooperation and Operation Condor Katie Zoglin

University of Miami Law School Institutional Repository University of Miami Inter-American Law Review 4-1-2001 Paraguay's Archive of Terror: International Cooperation and Operation Condor Katie Zoglin Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.law.miami.edu/umialr Part of the Foreign Law Commons, and the Human Rights Law Commons Recommended Citation Katie Zoglin, Paraguay's Archive of Terror: International Cooperation and Operation Condor, 32 U. Miami Inter-Am. L. Rev. 57 (2001) Available at: http://repository.law.miami.edu/umialr/vol32/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami Inter- American Law Review by an authorized administrator of Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PARAGUAY'S ARCHIVE OF TERROR: INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AND OPERATION CONDOR* KATIE ZOGLIN' I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 58 II. POLITICAL CONTEXT .................................................................................... 59 III. OVERVIEW OF PARAGUAY'S ARCHIVE OF TERROR ..................................... 61 A. Discovery Of The Archive Of Terror ...................................................... 61 B. Overview Of The Archive's Contents ....................................................... 63 IV. EVIDENCE OF OPERATION CONDOR IN THE ARCHIVE OF TERROR .............. 64 A. InternationalIntelligence Conferences -

River Rendezvous SOLD REF: 1208 Artist: FLEUR COWLES

River Rendezvous SOLD REF: 1208 Artist: FLEUR COWLES Height: 71.12 cm (28") Width: 180.34 cm (71") 1 Sarah Colegrave Fine Art By appointment only - London and North Oxfordshire | England +44 (0)77 7594 3722 https://sarahcolegrave.co.uk/river-rendezvous 29/09/2021 Short Description Fleur Fenton Cowles (nee Freidman), a formidable American journalist, socialite, hostess and artist, was born in New York. From the early 1930s she wrote a weekly fashion column for The New York World-Telegram. In 1937 she and her second husband, Atherton Pettingell, founded the advertising agency Pettingell & Fenton and counted Helena Rubenstein among her clients. Divorcing Pettingell in 1946 she left the advertising agency and on her marriage to the publisher Gardner Cowles she became associate editor at Look magazine, and year later, an associate editor at Quick magazine. In 1950 she founded the influential Flair magazine. Described in Time as “a fancy bouillabaisse of Vogue, Town & Country, Holiday etc”, it was highly praised for its design, contributors and lavish production but due to it’s high costs proved to be short lived. She moved to Europe in the late 1950s and alongside her life as a society hostess she also worked and exhibited as a painter and illustrator. He paintings are almost surrealistic and often feature flowers, big cats and dreamlike settings. She painting Desert Journey was reproduced as the cover of the 1968 Donovan album Donovan in Concert. She also designed tapestries, accessories and china for Denby Ltd and in 1959 wrote an authorised biography of Salvador Dali. Among her many achievements and posts she represented President Eisenhower at the Coronation of Elizabeth II, was senior fellow of the Royal College of Art in London and with her husband she helped build the Institute of American Studies in Oxford. -

Contemporary Civil-Military Relations in Brazil and Argentina : Bargaining for Political Reality

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1996 Contemporary civil-military relations in Brazil and Argentina : bargaining for political reality. Carlos P. Baía University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Baía, Carlos P., "Contemporary civil-military relations in Brazil and Argentina : bargaining for political reality." (1996). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 2541. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/2541 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. c CONTEMPORARY CIVIL-MILITARY RELATIONS IN BRAZIL AND ARGENTINA BARGAINING FOR POLITICAL REALITY A Thesis Presented by CARLOS P. BAIA Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS September 1996 Political Science © Copyright by Carlos Pereira Bafa 1996 All Rights Reserved CONTEMPORARY CIVIL-MILITARY RELATIONS IN BRAZIL AND ARGENTINA BARGAINING FOR POLITICAL REALITY A Thesis Presented by CARLOS P. BAIA Approved as to style and content by: Howard Wiarda, Chair Eric Einhorn, Member Eric Einhom, Department Head Political Science ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This work would not have been possible without the invaluable contributions of Howard Wiarda, Eric Einhorn, Timothy Steingega, Anthony Spanakos, Moise Tirado, Tilo Stolz, Edgar Brignoni, Susan Iwanicki, and Larissa Ruiz. To them I express my sincere gratitude. I also owe special thanks to the United States Department of Education for granting me a Foreign Language and Area Studies Fellowship to complete this research. -

Gloria Swanson

Gloria Swanson: An Inventory of Her Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Swanson, Gloria, 1899-1983 Title: Gloria Swanson Papers [18--]-1988 (bulk 1920-1983) Dates: [18--]-1988 Extent: 620 boxes, artwork, audio discs, bound volumes, film, galleys, microfilm, posters, and realia (292.5 linear feet) Abstract: The papers of this well-known American actress encompass her long film and theater career, her extensive business interests, and her interest in health and nutrition, as well as personal and family matters. Call Number: Film Collection FI-041 Language English. Access Open for research. Please note that an appointment is required to view items in Series VII. Formats, Subseries I. Realia. Administrative Information Acquisition Purchase (1982) and gift (1983-1988) Processed by Joan Sibley, with assistance from Kerry Bohannon, David Sparks, Steve Mielke, Jimmy Rittenberry, Eve Grauer, 1990-1993 Repository: Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin Swanson, Gloria, 1899-1983 Film Collection FI-041 Biographical Sketch Actress Gloria Swanson was born Gloria May Josephine Swanson on March 27, 1899, in Chicago, the only child of Joseph Theodore and Adelaide Klanowsky Swanson. Her father's position as a civilian supply officer with the army took the family to Key West, FL and San Juan, Puerto Rico, but the majority of Swanson's childhood was spent in Chicago. It was in Chicago at Essanay Studios in 1914 that she began her lifelong association with the motion picture industry. She moved to California where she worked for Sennett/Keystone Studios before rising to stardom at Paramount in such Cecil B. -

Lyrics by Tim Rice Music by Andrew Lloyd Webber Directed by Rob Ruggiero

2018–2019 SEASON EVITA LYRICS BY TIM RICE MUSIC BY ANDREW LLOYD WEBBER DIRECTED BY ROB RUGGIERO CONTENTS 2 The 411 3 A/S/L, HTH 4 FYI 6 B4U 7 IRL 8 RBTL At The Rep, we know HOW TO BE THE BEST AUDIENCE EVER! that life moves fast— TAKE YOUR SEAT okay, really fast. But An usher will seat your class as a group, and often we have we also know that a full house with no seats to spare, so be sure to stick with some things are your school until you have been shown your section in the worth slowing down theatre. for. We believe that live theatre is one of those pit stops worth making and are excited that you are going to stop SILENCE IS GOLDEN by for a show. To help you get the most bang for your buck, Before the performance begins, be sure to turn off your cell we have put together WU? @ THE REP—an IM guide that will phone and watch alarms. If you need to talk or text during give you everything you need to know to get at the top of your intermission, don’t forget to click off before the show theatergoing game—fast. You’ll find character descriptions resumes. (A/S/L), a plot summary (FYI), biographical information (F2F), BREAK TIME historical context (B4U), and other bits and pieces (HTH). Most This performance includes an intermission, at which time importantly, we’ll have some ideas about what this all means you can visit the restrooms in the lobby. -

Madonna's Postmodern Revolution

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, January 2021, Vol. 11, No. 1, 26-32 doi: 10.17265/2159-5836/2021.01.004 D DAVID PUBLISHING The Rebel Madame: Madonna’s Postmodern Revolution Diego Santos Vieira de Jesus ESPM-Rio, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil The aim is to examine Madonna’s revolution regarding gender, sexuality, politics, and religion with the focus on her songs, videos, and live performances. The main argument indicates that Madonna has used postmodern strategies of representation to challenge the foundational truths of sex and gender, promote gender deconstruction and sexual multiplicity, create political sites of resistance, question the Catholic dissociation between the physical and the divine, and bring visual and musical influences from multiple cultures and marginalized identities. Keywords: Madonna, postmodernism, pop culture, sex, gender, sexuality, politics, religion, spirituality Introduction Madonna is not only the world’s highest earning female entertainer, but a pop culture icon. Her career is based on an overall direction that incorporates vision, customer and industry insight, leveraging competences and weaknesses, consistent implementation, and a drive towards continuous renewal. She constructed herself often rewriting her past, organized her own cult borrowing from multiple subaltern subcultures, and targeted different audiences. As a postmodern icon, Madonna also reflects social contradictions and attitudes toward sexuality and religion and addresses the complexities of race and gender. Her use of multiple media—music, concert tours, films, and videos—shows how images and symbols associated with multiracial, LGBT, and feminist groups were inserted into the mainstream. She gave voice to political interventions in mass popular culture, although many critics argue that subaltern voices were co-opted to provide maximum profit. -

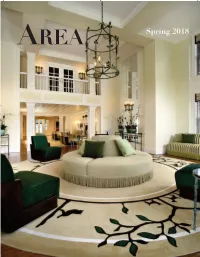

Spring 2018.Qxp Layout 1 3/7/18 8:14 AM Page 1

Covers - AREA spring 2018.qxp_Layout 1 3/7/18 8:14 AM Page 1 AREA Spring 2018 HORIZONS COLLECTION A NEW GENERATION OF DESIGNS kalaty.com MOMENI A TRADITION OF QUALITY same brand you love new look HIGH POINT launch party Saturday, APRIL 14, 5 PM, SHOWROOM H-345 www.momeni.com Invite your customers to experience island-inspired living at its fi nest through the refi ned yet casual Tommy Bahama area rug collection. FURNITURE AVAILABLE AT TBFURNITURE.COM HIGH POINT IHFC G.276 | OWRUGS.COM/TOMMY AreaMag_OW_FULL_TOMMY_Feb2018.indd 1 2/12/18 10:43 AM ta m ar ian www.tamarian.com The Sojourn Collection. See you at High Point Market. APRIL 14-18 | IHFC D-320 spring 2018 2.qxp_001 FALL 2006.qxd 3/7/18 8:05 PM Page 6 FROM THE PRESIDENT’S DESK Dear Colleagues, Fourth, on the positive side, there are great “Our Future Is Bright.” numbers of innovative and new rug designs being This phrase has been stuck in my head ever produced all the time, and we work in an industry since I recently read it in an article and made me in which the opportunities for being innovative think about it in depth. Some of you might agree are limitless. So, my friends, I think our future is with the phrase, but there are a few that would truly bright. think the opposite. They may say We just passed Atlanta and Las that trade shows do not draw the Vegas markets with the general same traffic as they used to, or “my mood being positive. -

Faces De Eva Estudos Sobre a Mulher FACES DE EVA Revista De Estudos Sobre a Mulher N.º Extra – 2019

ANO 2019 NÚMERO EXTRA Estudos sobre a Mulher sobre Estudos Faces deEva Faces Faces de Eva Estudos sobre a Mulher FACES DE EVA Revista de Estudos sobre a Mulher N.º Extra – 2019 Primeira Directora: Zília Osório de Castro Direcção: Zília Osório de Castro • Isabel Henriques de Jesus Coordenação: Aida Rechena, Ana Lúcia Teixeira, Teresa Veiga Furtado, Manuel Lisboa, Paulo Simões Rodrigues Assessora de Direcção: Natividade Monteiro Secretária de Edição: Maria do Céu Borrêcho Redacção: Alexandra Alves Luís, Ana Cristina Oliveira, Ana Ribeiro da Silva, Ana Rosa Mota, Catarina Inverno, Cristina L. Duarte, Elisabeth Évora Nunes, Ilda Soares de Abreu, Isabel Henriques de Jesus, João Esteves, Maria do Céu Borrêcho, Maria do Rosário Barardo, Maria José Remédios, Maria Reynolds de Souza (membro honorária), Natividade Monteiro, Regina Tavares da Silva (membro honorária), Rita Mira, Sandra Leandro, Susana Cámara Marín, Zília Osório de Castro. Conselho Editorial: Ana Guil Bozal (Universidade de Sevilha), Ana Isabel Buescu (Universidade NOVA de Lisboa), Ana Pires Pessoa (Instituto Politécnico de Setúbal), Anne Cova (Universidade de Lisboa), Bernardo Vasconcelos e Sousa (Universidade NOVA de Lisboa), Carla Cibele Figueiredo (Instituto Politécnico de Setúbal), Consuelo Flecha García (Universidade de Sevilha), Dalila Cerejo (Universidade NOVA de Lisboa), Deolinda Adão (Universidade da Califórnia - Berkeley), Esther Martínez Quinteiro (Universidade de Salamanca), Eugénia Vasques (Instituto Politécnico de Lisboa), Fernando Ribeiro (Universidade NOVA de Lisboa),