The Audience and the Star: Genre As the Interface and Expectation-Fulfillment As the Catalyst of Their Relationship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Southeast Bank ALLOTNO BANKCODE LOTTERYNO BONO NAME SHARES 059728 06-01-000006 0186741 1204570044777449 JANNATUL NAHIDA CHOWDHUR

SouthEast Bank ALLOTNO BANKCODE LOTTERYNO BONO NAME SHARES 059728 06-01-000006 0186741 1204570044777449 JANNATUL NAHIDA CHOWDHURY 200 059729 06-01-000011 0186746 1202420042849231 MD KHALILUR RAHMAN 200 059730 06-01-000018 0186753 1202420042319446 MD ABDUL JALIL & MST FOREDA PERVIN 200 059731 06-01-000019 0186754 1202420042849213 MD AKKAS ALI 200 059732 06-01-000021 0186756 1203020039271765 MOHAMMAD ALI ZINNAH 200 059733 06-01-000022 0186757 1203020039532499 MOHAMMAD ALI ZINNAH & MST.MOIFUL KHATUN 200 059734 06-01-000027 0186762 1202420042319411 MD.ABDUL JABBAR 200 059735 06-01-000029 0186764 1203020039271227 MST JOHURA BEGUM 200 059736 06-01-000031 0186766 1202420042849122 MD HARUNUR RASHID & HASINA AKTER 200 059737 06-01-000035 0186770 1202420042849280 MOST RABEYA BEGUM 200 059738 06-01-000038 0186773 1201960029726916 MD MONIR HOSSAIN 200 059739 06-01-000047 0186782 1203180010603381 MD MOIN KHAN 200 059740 06-01-000049 0186784 1202020001067901 MD ABU SAYEED GAZI 200 059741 06-01-000053 0186788 1203250024267641 FATEMA BEGUM 200 059742 06-01-000059 0186794 1201580018829375 MD ABU SAYEED GAZI & PARVEEN AKTER 200 059743 06-01-000062 0186797 1203250041716924 MERUNA KHAN 200 059744 06-01-000065 0186800 1204490044314257 MD RAZAUL KABER 200 059745 06-01-000072 0186807 1204490035049567 AKLIMA KHATOON 200 059746 06-01-000073 0186808 1204490027374444 KAZI SOHEB AFZAL 200 059747 06-01-000074 0186809 1204490039453651 KAZI SOHEB AFZAL & MOUSHUMI RAHMAN 200 059748 06-01-000084 0186819 1204390034305301 MD JUWEL RANA & MOSS MARIUM AKTER 200 059749 06-01-000087 -

Chorabali (Movie) (Online) (Download for Free)

(Yify) (Stream) Chorabali (Movie) (Online) (Download For Free) Search Result: ) Stream Chorabali Movie Online Download Free|( Stream Chorabali Movie Great Quality|(( Watch Chorabali Movie Full In Hd Now|)@ Stream Chorabali Movie Download|)@ Stream Chorabali Movie Download Full Links Movie Title: Chorabali Movie Description: A whodunit thriller set in the backdrop of North Kolkata with its British Raj charm that loosely based on the story of British Writer Agatha Christie. Run Time: 144 mins. Category: Thriller Producer: Subhrajit Mitra Actors: Mou Baidya, Malobika Banerjee, Tathagata Banerjee Movie Rating: - Year: (HD) (Stream) Chorabali (Movie) (Online) (Stream Or Download Now).html[2/17/2016 1:36:24 AM] (Yify) (Stream) Chorabali (Movie) (Online) (Download For Free) 2016 More Information About This Movie: Chorabali (2012) VCDRip Bengali Movie mkv - TorrentProject Top Ads. Label Links. Bangla Movie; Shakib Khan; Misha; Shabnur; Manna; Riaz; Apu Biswas Barun Chanda turns Hercule Poirot in Chorabali - Calcutta Chorabali Download Music>Bengali Movie Songs>Bengali Songs 2016>Chorabali Bengali Songs Chorabali avi 3gp mp4 movie music hd video ringtone wallpaper image picture ... India's 1st Online Movie Multiplex - ScreenPremiere.com Chorabali (2012) Bangla Movie 800 MB VCD RiP [Team TUT] 11 download locations kat.cr Chorabali 2012 Bangla Movie 800 MB VCD RiP E Subs Team TUT movies Chorabali Download Music>Bengali Movie Songs ... - wapzz.in Chorabali (2012) VCDRip Bengali Movie mkv torrent. Information about the torrent Chorabali (2012) VCDRip Bengali Movie mkv. Seeders, leechers and torrent status is ... Download Chorabali (2012) Bangla Movie 800 MB VCD RiP E ... Chorabali Mon Bangla Music Video (Tawsif Ul Haq) HD ..::Basic Info::. -

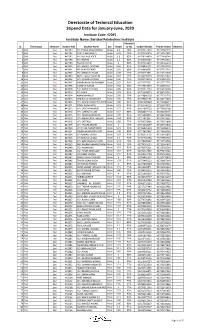

Directorate of Technical Education Stipend Data for January-June, 2020

Directorate of Technical Education Stipend Data for January-June, 2020 Institute Code: 42045 Institute Name: Barishal Polytechnic Institute Attenden SL Technology Semester Student Roll Student Name Sex Result ce (%) student Mobile Father Mobile Remarks 1 Civil 2nd 442793 MD.ESTIAK AZAM (RIDOY) Male 3.2 78% 01705212963 01735082535 2 Civil 2nd 442794 KHALID MAHAMUD Male 3.23 76% 01307636924 01719562981 3 Civil 2nd 442795 MILON HAWLADER Male 3.6 82% 01728109829 01771490244 4 Civil 2nd 442798 MD. RIMON Male 3.1 90% 01308685046 01319810061 5 Civil 2nd 442799 SAGOR GHOSH Male 3 88% 01300263462 01746604420 6 Civil 2nd 442800 MD. MARUF HOSSAIN Male 3.55 91% 01308836252 01723929128 7 Civil 2nd 442801 BISHWAJIT BEPARY Male 3.76 89% 01308838581 01765371331 8 Civil 2nd 442802 MD. MIRAZUL ISLAM Male 3.79 75% 01306019471 01756572603 9 Civil 2nd 442803 ABDULLAH AL MAMUN Male 3.57 77% 01634570579 01920115016 10 Civil 2nd 442804 MD. MONIR HOSSAIN Male 3.45 76% 01893574054 01706891391 11 Civil 2nd 442807 MAHBUBA ALOM SHAMME Male 3.67 92% 01725777551 01725777551 12 Civil 2nd 442808 NAZMUN NAHAR Male 3.93 88% 01319823403 01740882442 13 Civil 2nd 442809 S.M. NAZMUL ISLAM Male 3.65 93% 01762312233 01764319180 14 Civil 2nd 442810 MD.SAKIB Male 3.93 91% 01752699325 01300519541 15 Civil 2nd 442814 ANAN MAHMUD Male 2.95 78% 01319890258 01727261720 16 Civil 2nd 442815 KHAIRUL ALOM MEAIED Male 3.55 76% 01739962196 01760772063 17 Civil 2nd 442816 MD. RUMAN HOSSEN SIKDER Male 3.48 82% 01991909609 01715308412 18 Civil 2nd 442821 RIDOY HOWLADER Male 3.21 83% 01762246156 01766971072 19 Civil 2nd 442823 MD. -

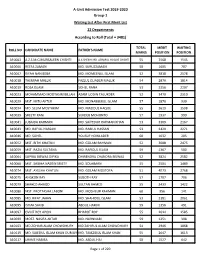

A-Unit Admission Test 2019-2020 Group-1 Waiting List After First Merit List 22 Departments According to Roll (Total = 3481)

A-Unit Admission Test 2019-2020 Group-1 Waiting List After First Merit List 22 Departments According to Roll (Total = 3481) TOTAL MERIT WAITING ROLL NO CANDIDATE NAME FATHER'S NAME MARKS POSITION POSITION A10003 A.Z.S.M.G.MURSALEEN CHISHTI A.A.SHEIKH MD. ASRARUL HOQUE CHISHTI 55 2568 1545 A10006 REEFA ZAMAN MD. SURUZZAMAN 58 1605 707 A10007 RIFAH NANJEEBA MD. MOMEENUL ISLAM 52 3818 2578 A10018 TASMIAH MALLIK FAZLUL QUADER MALLIK 54 2879 1814 A10019 ROZA ISLAM SOHEL RANA 53 3356 2207 A10023 MOHAMMAD MOOTASIM BILLAH AZAM UDDIN TALUKDER 52 3479 2310 A10029 MST. MITU AKTER MD. MONABBERUL ISLAM 57 1870 939 A10034 MD. SELIM MOSTAKIM MD. MAZIDUL HAQUE 55 2629 1598 A10039 SREETY RANI SUKDEB MOHONTO 57 1937 999 A10041 JUBAIDA RAHMAN MD. SAIYEDUR RAHMAN KHAN 53 3309 2167 A10043 MD. RAFIUL HASSAN MD. RABIUL HASSAN 53 3429 2271 A10046 MD. SOHEL YOUSUF HOWLADER 60 1032 205 A10052 MST. BITHI KHATUN MD. GOLAM RAHMAN 52 3688 2475 A10059 MST. RAZIA SULTANA MD. RAFIQUL ISLAM 59 1367 500 A10064 SUPRIA BISWAS DIPIKA DHIRENDRA CHANDRA BISWAS 52 3824 2582 A10066 MST. SABIHA NASRIN SRISTY MD. SOLAIMAN 55 2504 1489 A10074 MST. AYESHA KHATUN MD. GOLAM MOSTOFA 51 4073 2768 A10075 ANGKON RAY SUBOTH RAY 57 1707 796 A10079 SHAHED AHMED SULTAN AHMED 55 2433 1422 A10080 MST. PROTTASHA LABONI MD. MOSHEUR RAHMAN 60 956 141 A10085 MD. RIFAT JAHAN MD. SHAHIDUL ISLAM 53 3181 2061 A10095 ISTIAK SAKIB ABDUL HAKIM 59 1356 491 A10097 OVIJIT ROY APON BHAROT ROY 55 2614 1585 A10099 MOST. NASIFA AKTAR MD. -

Representation of Women in Contemporary Bangladeshi Movies: an Analysis

Representation of Women in Contemporary Bangladeshi Movies: An Analysis Anukriti Aditya ID: 163-24-573 Program: BSS (Honors) Department of Journalism and Mass Communication Faculty of Humanities and Social Science Daffodil International University, Dhaka, Bangladesh August 2020 Representation of Women in Contemporary Bangladeshi Movies: An Analysis Submitted To Mr.Anayetur Rahaman Lecturer Department of Journalism and Mass Communication Faculty of Humanities and Social Science Daffodil International University By Anukriti Aditya ID: 163-24-573 In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements B.S.S (Hons) in Journalism and Mass Communication August 2020 Letter of Approval This is to certify that Anukrity Aditya, ID: 163-24-573, has conducted herresearch project titled “Representation of Women in Contemporary Bangladeshi Movies: An Analysis,”under my supervision and guidance. The study has been undertaken in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Social Science (BSS) in Journalism and Mass Communication at Daffodil International University. The study is expected to contribute in the field of Journalism and Mass Communication as well as in further study about the country‟s film industry. ………………………………………… Anayetur Rahaman Lecturer Department of Journalism and Mass Communication Daffodil International University Application for approval of dissertation Mr.Anayetur Rahaman Lecturer Department of Journalism and Mass Communication Daffodil International University Subject: Application for submission of my dissertation for approval Dear Sir, I have accomplished my dissertation “Representing Women in Contemporary Bangladeshi Cinema” as a course requirement for my under-graduate programme. I have tried my best to work with sincerity to cover all aspects regarding the matter which I have been assigned. -

IMANA Impact Report-2018-Single.Indd 1 1/23/2019 1:52:23 PM IMANA Impact Report-2018-Single.Indd 2 1/23/2019 1:52:31 PM 3

IMPACT REPORT IMANA Medical Relief IMANA Impact Report-2018-Single.indd 1 1/23/2019 1:52:23 PM IMANA Impact Report-2018-Single.indd 2 1/23/2019 1:52:31 PM 3 IMANA Impact Report-2018-Single.indd 3 1/23/2019 1:52:36 PM Letter from the President .........................................................................................................5 IMANA Leadership.....................................................................................................................6 Evenings with IMANA ................................................................................................................7 Conventions Attended ..............................................................................................................8 Strategic Plan Update ................................................................................................................9 CME Conferences ....................................................................................................................10 Donation Data ..........................................................................................................................11 Membership Data ....................................................................................................................12 IMR Statistics ............................................................................................................................14 IMR Mission Impact in 2017 ...................................................................................................16 -

P36-40 Layout 1

WEDNESDAY, APRIL 12, 2017 lifestyle MUSIC & MOVIES Thriller 'Trivisa' wins big at Hong Kong Film Awards rime thriller "Trivisa" was the big winner at the Hong Kong Film Awards, taking home five awards Cincluding the prize for best film. The movie, which takes place on the eve of the Hong Kong's 1997 han- dover from Britain, also took home awards for best director and best actor on Sunday evening. News sites in mainland China downplayed their coverage, which Hong Kong media speculated was because one of its directors worked on 2016's "Ten Years," about Beijing's tightening grip on the semiautonomous city. Best actress went to "Happiness" star Kara Hui. She won her fourth Hong Kong Film Award for playing a middle-aged recluse suffering from Alzheimer's. Family- themed movie "Mad World" was another big winner, receiving trophies for best supporting actor and actress and best new director. — AP The crew of movie "Trivisa" celebrate after winning the Best Actor and Best Film awards during the Hong Kong Film Awards in Hong Kong, Sunday. — AP photos Hong Kong actress Kara Wai, left and actor Gordon Lam pose after winning the Best Hong Kong actor Eric Tsang poses after winning the Best Hong Kong actor Gordon Lam, center, poses with his colleagues actors Philip Keung, Actress and Best Actor awards. Supporting Actor award for his movie "Mad World". right, and Richie Ren after winning the Best Actress and Best Actor awards. Box Office Top 20: 'The Boss Baby' Bangladesh stars' secret squashes 'Smurfs 3' marriage sparks web sensation he Boss Baby" continued to dominate the box office release, as compiled Monday by comScore: in its second weekend in theaters, adding $26.4 mil- 1. -

The Emotional Man Fame and Facts in Bangladesh

Images and Text Copyright 2010 Leonid Plotkin The Emotional Man Fame and Facts in Bangladesh 3300 Words him national awards. Still, in the streets nobody both- Contact: [email protected] ered him. “All people love me, but nobody knows what I look like,” was how he explained it. There were facts. But the facts didn’t matter. For me it was different. Some are born famous. Some become famous for their accomplishments. And some are just famous for Crowds gathered wherever I went. Shy students asked being famous. me to pose with them for a photo. Nursing mothers gave me their babies to hold. At Sufi shrines people In Bangladesh I was famous for no reason at all. And forgot about their saints and fakirs and swarmed me it would be more accurate still to say I was not at all instead. And smiling passersby gawked and pointed famous. But people treated me like a poster-boy come and winked at me in the streets. Foreigners are rare in to life – and that was before The Director gave me a Bangladesh. role in his film. I felt like a poster-boy, and the posters hung every- The Director was famous for making bad movies. His where – movie posters that covered every blank wall films played up and down Bangladesh and brought in the country. They were complex, multilayered 1 Images and Text Copyright 2010 Leonid Plotkin lurid montages, these posters – a Bangladeshi brew of A tangle of passersby stopped to look at me looking at sentimentality and violence. The slinky seductress; the poster. -

16Th Convocation (2017): List of Graduates

16th Convocation (2017): List of Graduates Semester of Sl. Student_ID Student_Name Major Academic Achievement Completion 1 2001-3-10-039 Md. Shafiqul Islam Accounting None Summer 2008 2 2003-2-10-206 Farjana Rashid Marketing None Fall 2008 3 2004-3-10-002 Sayem Mahmud Forkan Marketing None Fall 2008 4 2005-1-10-219 Joynal Abedin Marketing None Fall 2008 5 2005-2-10-156 Khandaker. Muradul. Haque Marketing None Fall 2009 6 2005-3-10-104 Md. Mozidul Islam Accounting None Spring 2012 7 2007-2-10-042 Shirin Islam Management Information System None Spring 2012 8 2008-3-10-038 Md. Shafiar Rahman Rana Finance None Fall 2012 9 2008-3-10-052 Md. Asraful Islam Marketing None Fall 2013 10 2008-3-10-058 Yasir Bin Morshed Marketing None Summer 2015 11 2008-3-10-067 Piplu Karmakar Marketing None Spring 2016 12 2008-3-10-180 Parvin Sultana Finance None Summer 2013 13 2009-1-10-099 Md. Zahid Akand Shihan Marketing None Fall 2015 14 2009-1-10-166 Huzzatul Murshed Finance None Summer 2013 15 2009-1-10-194 Sheikh Md. Arefin Accounting None Fall 2013 16 2009-1-10-260 Noor Ullah Patwary Human Resource Management None Spring 2015 17 2009-2-10-096 Md. Shafiqul Alamm Finance None Spring 2014 18 2009-2-10-126 Md. Rashdushzaman Khan Marketing None Fall 2013 19 2009-2-10-128 Tanjirul Islam Bappy Marketing None Fall 2015 20 2009-2-10-233 Md. Shahinur Rahman Marketing None Fall 2016 Page 1 of 99 Semester of Sl. -

Representation of Women in Electronic Visual Media: Bangladeshi Context

Representation of Women in Electronic Visual Media: Bangladeshi Context Orchi Othondrila Student ID: 12263008 Department of English and Humanities December 2014 BRAC University, Dhaka, Bangladesh ii Representation of Women in Electronic Visual Media: Bangladeshi Context A Thesis Submitted to The Department of English and Humanities Of BRAC University By Orchi Othondrila Student ID: 12263008 In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Arts in English December 2014 iii Acknowledgements I am extremely grateful to my supervisor Professor Syed Manzoorul Islam who helped and encouraged me not only for this paper but also for the post-graduation courses. I am thankful to the Chairperson of English and Humanities Department Professor Firdous Azim who has always shown her concern and advised me for my welfare. Also, it was impossible to complete my masters without support of my parents. iv Table of Contents Abstract v Introduction 1 Chapter 1 Women in Cinema 5 Chapter 2 Popular Soap Opera on Television 10 Chapter 3 Television Advertisement 16 Chapter 4 Women on Internet 23 Conclusion 31 Works Cited 34 Appendices 37 v Abstract Stereotyping based on gender is a very common phenomenon around the world since early days of civilization. Physical difference might be the basic reason of male-female division, but the distinction evolved into an ideological one that established a misogynistic tradition of putting women as nurses for men. Seeing women only in terms of their body also emerged in visual media as the division was already established as form of culture. Bangladesh is not an exception in viewing women in similar ways in the media. -

US Welcomes Return of Hekmatyar Extends

Eye on the News [email protected] Truthful, Factual and Unbiased Vol:XI Issue No:268 Price: Afs.20 www.afghanistantimes.af www.facebook.com/ afghanistantimeswww.twitter.com/ afghanistantimes TUESDAY . MAY 02. 2017 -Sawar 12, 1396 HS By Farhad Naibkhel Hadith, those who make difficult soil from any sort of aggression is otherwise, at the future they the live of people, closing ways called Jihad, where security forc- would pay 20 times more com- KABUL: The ongoing fighting of and harassing them, is not called es are doing this.” Pointing toward pensation as much as they did the Taliban insurgents is not Ji- Jihad. “Currently, not only peo- rifts among the National Unity with us.” He added that “we don’t had at all, and they (Taliban) ple’s live have become difficult, Government (NUG) leaders, seek enmity with any country,” should not be tempted through but their massacre is going on, Sayyaf called on the both leaders but at the same time he asked all fake fatwa’s, a powerful ex-Jihaid thus they (militants) by practic- to end tensions. He added that we the neighboring countries not to leader said on Monday. ing this evil designs should not call are not in view for the collapse of misuse from current weakness and During commemorating the this as Jihad,” he added. He fur- the current system, but he warned challenges. Praising the interna- 25th anniversary of Mujahedeen ther went on saying, killing of in- that “if internal rifts not resolved tional community’s donation and victory, Jihadi leader, Abdul Rab nocent people, women and chil- the nation would be sinking in it.” support, Sayyaf asked them to Rassoul Sayyaf called on the Tal- dren is forbidden in Islam. -

Saheb Bengali 3Gp Movie Free Download

Saheb Bengali 3gp Movie Free Download Saheb Bengali 3gp Movie Free Download 1 / 3 2 / 3 Get the complete list of Kabir Bhajan mp3 songs free online. Find the best place to Kabir Bhajan movie songs download list. Download Hungama Music app to .... Listen to all Hindi Albums and Hindi Movie songs on JioSaavn for Free. ... HindiEnglishTamilTeluguPunjabiMarathiGujaratiBengaliKannadaBhojpuriMalayalamUrdu ... Aao Sangate Hazoor Sahib Chaliye Baajaan Wala Awaaza Maarda (Vol.. Truth has come, documentary by As Sahab Media, with Bengali subtitles. Part 1: Low quality - Jhq1low.3gp Medium quality - Jhqp1med.mp4 .... telugu sex videos, Aunty sex xxx 3gp movie porn film, fresh mp4 xnxx hd young girls aunty xxx telugu Sex Videos free download indian sex,. 9857 bengali actress swastika FREE videos found on XVIDEOS for this search. ... Swastika Mukherjee New Hot Movie clips. 3 minBollywoodhot - 3M Views -.. Latest comedy Movies: Check out the list of all latest comedy movies released in 2020 along with trailers and reviews. Also find details of theaters in which latest .... Download latest hindi Bollywood, Hollywood, South indian and all category movies you can download on Mp4moviez with HD formats ... Love Ke Liye Kuch Bhi Karega (2001) Hindi DVD Full Movie ... Saheb Biwi Aur Gangster (2011) DVDRip.. Machhli Jal Ki Rani Hai 2014 Hindi Full Movie Watch Online Free. Free Mp3 তাই তাই তাই Tai Tai Tai Bengali Rhymes For Children Jugnu Kids Bangla Download ... Jal 3 movie in hindi free download 3gp. ... The most accurate version on the internet. pls upload kanchana2 480p in hindi and raja saheb ki haweli in hindi . 1:13.