SUBMISSION to the NSW TRANSPORT BLUEPRINT September 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Western Sydney Airport Fast Train – Discussion Paper

Western Sydney Airport Fast 2 March 2016 Train - Discussion Paper Reference: 250187 Parramatta City Council & Sydney Business Chamber - Western Sydney Document control record Document prepared by: Aurecon Australasia Pty Ltd ABN 54 005 139 873 Australia T +61 2 9465 5599 F +61 2 9465 5598 E [email protected] W aurecongroup.com A person using Aurecon documents or data accepts the risk of: a) Using the documents or data in electronic form without requesting and checking them for accuracy against the original hard copy version. b) Using the documents or data for any purpose not agreed to in writing by Aurecon. Disclaimer This report has been prepared by Aurecon at the request of the Client exclusively for the use of the Client. The report is a report scoped in accordance with instructions given by or on behalf of Client. The report may not address issues which would need to be addressed with a third party if that party’s particular circumstances, requirements and experience with such reports were known and may make assumptions about matters of which a third party is not aware. Aurecon therefore does not assume responsibility for the use of, or reliance on, the report by any third party and the use of, or reliance on, the report by any third party is at the risk of that party. Project 250187 DRAFT REPORT: NOT FORMALLY ENDORSED BY PARRAMATTA CITY COUNCIL Parramatta Fast Train Discussion Paper FINAL DRAFT B to Client 2 March.docx 2 March 2016 Western Sydney Airport Fast Train - Discussion Paper Date 2 March 2016 Reference 250187 Aurecon -

Macquarie Park Bus Network Map Mona Vale to Newcastle 197 Hornsby 575 Hospital Ingleside N 575 Terrey Hills

Macquarie Park bus network map Mona Vale To Newcastle 197 Hornsby 575 Hospital Ingleside N 575 Terrey Hills East Wahroonga St Ives 575 Cherrybrook Castle Hill 619 621 Turramurra 651 Gordon 651 619 621 West Beecroft Baulkham Hills Pennant Hills 295 North Epping South Turramurra To 740 565 Lindfield Plumpton 630 M2 Motorway Stations 575 Yanko Rd West Lindfield 651 740 UTS Kuring-gai 611 619 621 651 611 M54 140 290 292 North Rocks 611 630 Chatswood Marsfield 288 West Killara 545 565 630 619 740 M54 Epping To Blacktown Macquarie 545 611 630 Carlingford Park Macquarie North Ryde Centre/University Fullers Bridge M41 Riverside 292 294 Corporate Park 459 140 Eastwood 506 290 Oatlands 621 651 M41 518 288 Dundas 459 545 289 507 506 M54 Valley North Ryde Denistone M41 288 550 544 East 459 289 North Parramatta Denistone Lane Cove West East Ryde Dundas Ermington 506 Ryde 507 Gore Hill 288 292 Boronia Park 140 Meadowbank 294 Parramatta 289 M54 545 550 507 290 621 To Richmond 651 & Emu Plains 518 Hunters Hill St Leonards Silverwater 140 To Manly Putney Crows Nest M41 Gladesville 459 507 North Sydney Rhodes City - Circular Quay Concord M41 506 507 518 Hospital Drummoyne Concord West City - Wynyard Rozelle North Strathfield Concord Auburn M41 White Bay City - QVB 544 288 290 292 Strathfield 459 Burwood 294 621 651 To Hurstville M41 Legend Busways routes Rail line Forest Coach Lines routes Railway station Hillsbus routes Bus route/suburb Sydney Buses routes Bus/Rail interchange TransdevTSL Shorelink Buses routes Diagrammatic Map - Not to Scale Service -

CBD and South East Light Rail Environmental Impact Statement

A Submission by EcoTransit Sydney to the CBD and South East Light Rail Environmental Impact Statement Prepared by EcoTransit Sydney 9 December 2013 Principal Author: Mr Tony Prescott Authorised by the Executive Committee of EcoTransit Sydney Contact person for this submission: Mr Gavin Gatenby Co-Convenor, EcoTransit Sydney Mob: 0417 674 080 P: 02 9567 8502 E: [email protected] W: ecotransit.org.au The Director General Department of Planning and Infrastructure CBD and South East Light Rail Project – SSI 6042 23–33 Bridge Street, Sydney NSW 2000 9 December 2013 Dear Sir, Please find enclosed a submission from EcoTransit Sydney to the CBD and South East Light Rail Environmental Impact Statement. EcoTransit Sydney1 is a long standing, community-based, public transport and active transport advocacy group. It is non-party political and has made no reportable political donations. Yours sincerely, John Bignucolo Secretary EcoTransit Sydney 1 www.ecotransit.org.au THE SYDNEY CBD SOUTH EAST LIGHT RAIL (CSELR): RESPONSE TO ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT SUBMISSION BY ECOTRANSIT SYDNEY 9 DECEMBER 2013 CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................5 1.1 Background to this submission ..................................................................5 1.2 The issues ...............................................................................................5 1.3 Summary of key recommendations ............................................................5 2 SYSTEM -

Department of Transport Annual Report 2010-11 Contents

Department of Transport Annual Report 2010-11 Contents Overview 3 Letter to Ministers from Director General 4 Director General overview 6 About us 7 Vision 8 Values 9 How transport has changed 10 Department of Transport at a glance 14 Management and structure 16 Corporate Framework 18 Corporate Plan 19 NSW State Plan 20 Review of operations 21 Improving Infrastructure 22 Commuter carparks and transport interchange 22 Level crossings 22 Inner West Busway 22 Rail station upgrades 23 South West Rail Link 23 Inner West Light Rail Extension 23 Wynyard Walk 23 Improving public transport services 25 Overview 25 Rail 26 Bus 28 Ferry 31 Taxi 32 Roads 34 Freight 35 Air transport 36 Improving local and community transport 37 Improving transport planning 40 Improving customer service 44 Transport Info 131500 44 Bureau of Transport Statistics 46 Transport Management Centre 48 Coordinating public transport for major events 49 Wayfinding and customer information 51 Security and emergency management 51 Fares and ticketing 51 Customer satisfaction surveys 51 Stakeholders and clients 53 Financial statements 55 Department of Transport 56 Sydney Metro 113 Appendices 147 Contact details 191 Overview Department of Transport Annual Report 2010-11 3 Letter to Ministers from Director General The Hon Gladys Berejiklian MP The Hon Duncan Gay MLC Minister for Transport Minister for Roads and Ports Parliament House Parliament House Macquarie Street Macquarie Street Sydney NSW 2000 Sydney NSW 2000 Dear Ministers I am pleased to submit the Annual Report for the Department of Transport for the year ended 30 June 2011 for tabling in Parliament. This Annual Report has been prepared in accordance with the Annual Reports (Departments) Act 1985. -

Fixing Town Planning Laws

Fixing town planning laws Identifying the problems and proposing solutions Submission by the Urban Taskforce to the Productivity Commission in response to its issues paper: Performance Benchmarking of Australian Business Regulation: Planning, Zoning and Development Assessments September 2010 Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................................... 5 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................................................... 10 1.1 This submission focuses on NSW ................................................................................................................... 10 1.2 Allan Fels report: Choice Free Zone ............................................................................................................ 14 1.3 Going Nowhere and Deny Everything reports ......................................................................................... 15 1.4 NSW Government’s own reports ................................................................................................................. 18 1.5 Anti-competitive features of the planning system.................................................................................. 19 2. The objectives of the planning system ............................................................................................................ 26 2.1 The current objectives .................................................................................................................................. -

S2B EIS Vol 1A Chapters 5 to 7

5. Project need This chapter describes the need for the project, strategic context, and project benefits. The Secretary’s environmental assessment requirements addressed by this chapter are listed in Table 5.1. A full copy of the assessment requirements and where they are addressed in the Environmental Impact Statement is provided in Appendix A. Table 5.1 Secretary’s environmental assessment requirements – project need Ref Secretary’s environmental assessment requirements – Where addressed project need 2.1(d) A summary of the strategic need for the project with regard to its critical This chapter State significance and relevant State Government policy. 5.1 Need for the project The project consisting of the upgrade of the T3 Bankstown Line between Marrickville and Bankstown is needed for three key reasons: 1. To meet the growing demand for services on the T3 Bankstown Line. 2. To resolve current accessibility and safety improvement issues on the T3 Bankstown Line. 3. To relieve existing bottleneck and capacity issues affecting the T3 Bankstown Line and the overall rail network. In addition to these localised needs, the project would contribute to the regional needs of a growing population and aid in the response to housing and job demands. It would also promote improved liveability through better public transport opportunities by: contributing to population and economic growth in Sydney helping to meet increasing community demand for public transport responding to housing demands in Sydney. The local and regional needs, issues and drivers -

Planning Cultural Creation and Production in Sydney: a Venue and Infrastructure Needs Analysis

Planning Cultural Creation and Production in Sydney A venue and infrastructure needs analysis April 2018 Ien Ang, David Rowe, Deborah Stevenson, Liam Magee, Alexandra Wong, Teresa Swist, Andrea Pollio WESTERN SYDNEY UNIVERSITY Institute for Culture and Society The Project Team Distinguished Professor Ien Ang Emeritus Professor David Rowe Professor Deborah Stevenson Dr. Liam Magee Dr. Alexandra Wong Dr. Teresa Swist Mr. Andrea Pollio ISBN 978-1-74108-463-4 DOI 10.4225/35/5b05edd7b57b6 URL http://doi.org/10.4225/35/5b05edd7b57b6 Cover photo credit: City of Sydney Referencing guide: Ang, I., Rowe, D., Stevenson, D., Magee, L., Wong, A., Swist, T. & Pollio, A. (2018). Planning cultural creation and production in Sydney: A venue and infrastructure needs analysis. Penrith, N.S.W.: Western Sydney University. This is an independent report produced by Western Sydney University for the City of Sydney. The accuracy and content of the report are the sole responsibility of the project team and its views do not necessarily represent those of the City of Sydney. 2 Acknowledgements This project was commissioned by the City of Sydney Council and conducted by a research team from Western Sydney University’s Institute for Culture and Society (ICS). The project team would like to acknowledge Lisa Colley’s and Ianto Ware’s contribution of their expertise and support for this project on behalf of the City of Sydney. We also extend our gratitude to the other City of Sydney Council officers, cultural venue operators, individual artists, creative enterprises, and cultural organisations who participated in and shared their experiences in our interviews. -

Parramatta Light Rail News Update February 2019 Newsletter

Parramatta Light Rail News Update February 2019 Newsletter Parramatta Light Rail construction to begin Carlingford STAGE 1 STAGE 2 16 stops 10–12 stops Melrose Park WARATAH ST Rydalmere Ermington PARRAMATTA RIVER SOUTH ST BORONIA ST Wentworth Point Westmead HILL RD Parramatta CBD Camellia AUSTRALIA AVE Sydney Olympic Park Carter Street DAWN FRASER AVE Stage 1 route Stage 2 preferred route Stage 2 – alternative Camellia alignment under consideration Artist’s impression of light rail in Macquarie Street in the Parramatta CBD. Construction of the $2.4 billion Parramatta Light Rail will begin this year after two major contracts were awarded to build and operate Parramatta Light Rail Stage 1, connecting Westmead to Carlingford via Parramatta CBD and Camellia along a 12-kilometre network. Parramatta Light Rail is on its way vehicles for the Inner West and The Parramatta Light Rail is expected following the signing of contracts Newcastle light rail networks. to commence services in 2023. to deliver the $2.4 billion project. The NSW Government is working Transport for An $840 million major contract to hard to mitigate construction build the light rail was awarded to impacts, introducing construction NSW is committed Downer and CPB Contractors in a ‘grace periods’ over the summer to providing joint venture, while a $536 million months in the key dining precinct regular project contract to supply and operate the of Eat Street, working to a flexible updates, maps network was awarded to the Great construction schedule and signing and construction notifications for River City Light Rail consortium agreements with the major utility residents, local businesses and that includes Transdev, operator of providers. -

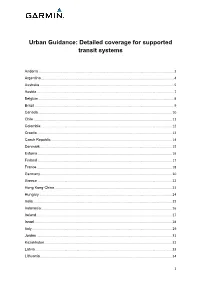

Urban Guidance: Detailed Coverage for Supported Transit Systems

Urban Guidance: Detailed coverage for supported transit systems Andorra .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Argentina ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Australia ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Austria .................................................................................................................................................... 7 Belgium .................................................................................................................................................. 8 Brazil ...................................................................................................................................................... 9 Canada ................................................................................................................................................ 10 Chile ..................................................................................................................................................... 11 Colombia .............................................................................................................................................. 12 Croatia ................................................................................................................................................. -

New Western Sydney Museum 15

.;'" it* 'iil ,,,il ,, .l :." -|-l OJ Tr-.h c) o) f o- tr -l OJ o)s :J c.) v) 5 E 3 o rD ,11-l a - otJr ltr v, ;1''. , '. 3 o :) r'+ Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences November 2016 Traffic and Transport Assessment 161372UT Revision Register 11t11t16 For FinalBusiness Case Taylor Thomson Whitting (NSW) Pty Ltd Page 2 of 41 @ 2016 Taylor Thomson Whitting Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences November 2016 Traffic and Transport Assessment 161372UT Appendix A - Intersection Analysis 34 AppendixB-TimberLane 39 Appendix C - Turning Paths 40 Appendix D - Trip Distribution 41 List of Figures Figure 2.1: Site Location .............7 Figure 2.2: Intersection survey locations .......9 Figure 2.3: Peak 60-minute traffic volumes at Phillip Street & Church Street ...................... 10 Figure 2.4:Peak 60-minute traffic volumes at Phillip Street & Wilde Avenue ...................... 10 Figure 2.5: Peak 60-minute traffic volumes at Wilde Avenue & Victoria Road..................... 11 Figure 2.6: Peak 60-minute traffic volumes at Phillip Street & George Khattar Lane........... 11 Figure 2.7: Bus routes servicing the New Museum site............ ....... 13 Figure 2.8: Potential light rail alignments through Parramatta CBD.......... ......... 16 Figure 2.9: Example of pedestrian wayfinding signage in CBD .......17 Figure 2.10:Walking distance to on- and off-street parking areas......... ............ 18 Figure 2.11: Visitor overlap at the Powerhouse Museum ................20 Figure 2.12: Arrival and departure movements from Powerhouse Museum surveys ...........21 Figure 3.1: Powerhouse Museum staff location by postcode...,.......... ...............23 Figure 3.2: Vehicle movements scaled by expected visitation and mode share...................30 List of Tables Table 2.1: Peak 60-minute traffic volumes (intersection totals).... -

Sustainable Neighbourhoods in Australia Raymond Charles Rauscher · Salim Momtaz

Sustainable Neighbourhoods in Australia Raymond Charles Rauscher · Salim Momtaz Sustainable Neighbourhoods in Australia City of Sydney Urban Planning 1 3 Raymond Charles Rauscher Salim Momtaz University of Newcastle University of Newcastle Ourimbah, NSW Ourimbah, NSW Australia Australia ISBN 978-3-319-17571-3 ISBN 978-3-319-17572-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-17572-0 Library of Congress Control Number: 2015935216 Springer Cham Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2015 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. Cover image: Woolloomooloo Square (Forbes St) developed from street closure (see Chapter 3 on Woolloomooloo). -

Another Project

A NOTHE R P R O J ECT a new beginning, life at RISE brand new residential community is coming A soon to Hurlstone Park. Imagine a new home, a new neighbourhood, and a fresh new life where everything you need is close at hand. Experience the essence of RISE. It’s contemporary easy living that you and your family have always dreamed about. Hawthorne 5 Sydney CBD 3 Sydney University Leichhardt North 4 Marion Taverners Hill Lewisham West Newtown Cafe Strip . Waratah Mills Dulwich Grove Arlington Sydney Light Rail Line 6 Hurlstone Park RSL Marrickville 2 Town Centre 1 Dulwich Hill Station & Interchange welcome to 7 Hurlstone Park Station RISE ocated just 9km from the Sydney CBD, Hurlstone’s LRise Apartments is only minutes from Newtown’s lively cafe strip, Sydney University, Royal Prince Alfred Hospital and all the best that Inner West of Sydney has to offer. Living at RISE means being well connected! There’s also a handy bus stop nearby, and you’re just a short walk from Hurlstone Park Train Station and the Dulwich Grove LIght Rail Station. The M5 Motorway, conveniently located less than 3km away, provides direct and easy access to the city and Sydney Airport. Artists Impression Only luxury apartments resh and inviting, RISE provides comtemporary Fapartments offering brand new level of luxury in an area you’ll love to live in. RISE is designed to blend with the residential character of the surrounding area with the perfect mix of traditional and contemporary architectural style. For peace of mind it features controlled entry and security features.