The Historical Continuity of Criminal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Voluntary Refusal to Commit a Crime: Significance, General and Special Signs

1884 International Journal of Criminology and Sociology, 2020, 9, 1884-1888 Voluntary Refusal to Commit a Crime: Significance, General and Special Signs Sergej N. Bezugly, Evgenij A. Ignatenko*, Elena F. Lukyanchikova, Oksana S. Shumilina and Natalia Yu. Zhilina Belgorod State University, 85 Pobedy Street, Belgorod, 308015, Russian Federation Abstract: The article describes and examines the significance of the rule of the voluntary refusal to commit a crime, as well as explores its general and special signs. It is noted that the voluntary refusal to commit a crime is the rule contained in any modern, progressive law. In this vein, there are different theoretical approaches to the determination of its value and signs. The signs are debatable in nature, and their establishment by the law enforcer may cause difficulties. The difference between voluntary refusal to commit a crime, which is implemented in three functions, is determined, definitions of general signs of voluntary refusal are proposed, their content is clarified. Special signs of voluntary refusal are disclosed. Keywords: Voluntary refusal to commit a crime, signs of voluntary refusal, stages of a crime, preparation for a crime, attempted crime, criminal liability. INTRODUCTION instance, Greenawalt investigates communications that can lead to antisocial behaviour. Moreover, he Each rule of criminal law has its significance, which concentrates on criminal counselling and vaguer is subject to theoretical understanding. Voluntary advocacy of crime, that is to say, definitions refusal to commit a crime implements several encouraging illegal actions. However, the discussion necessary socially useful, humanistic, economic also covers provocative comments that trigger hostile, functions. violent responses, as well as to disclosures of the reality that supplies incentives to commit crimes or help The issue of signs of voluntary refusal is highly with their commission. -

History of Russia

Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Education “Irkutsk State Medical University” of the Ministry of Healthcare of the Russian Federation Department of Social Psychology and Humanities A. V. Zavialov, О. V. Antipina HISTORY OF RUSSIA Study guide Irkutsk ISMU 2019 1 УДК 94(470)(075.8)=111 ББК 63.3(2)я73 Z 39 Recommended by the CCMС of FSBEI HE ISMU MOH Russia as a study guide for foreign students, mastering educational programs of higher education by the educational program of the specialty of General Medicine for mastering the discipline “History” (Protocol № 4 of 11.06.2019) Authors: A. V. Zavialov – Candidate of Sociological Sciences, Senior teacher, Department of Social Psychology and Humanities, FSBEI HE ISMU MOH Russia O. V. Antipina – Candidate of Philological Sciences, Associate Professor, Department of Foreign Languages with Latin and “Russian for Foreigners” Programs, FSBEI HE ISMU MOH Russia Reviewers: P. A. Novikov – Doctor of Historical Sciences, Professor, Head of the Department of History and Philosophy, FSBEI HE INRTU R. V. Ivanov – Candidate of Historical Sciences, Associate Professor, Department of State and Municipal Administration, FSBEI HE ISU Zavialov, A. V. Z 39 History of Russia : study guide / A. V. Zavialov, О. V. Antipina ; FSBEI HE ISMU MOH Russia, Department of Social Psychology and Humanities. – Irkutsk : ISMU, 2019. – 148 p. The study guide covers the key concepts and events of Russian history, beginning from the times of Rus’ up to the present days, and helps a student develop his/her reading and presentation skills. The educational material is presented as texts of four main sections of the course, where the term in English is accompanied with its Russian equivalent, while the explanation is given in English. -

The Abandonment Defense

European Journal of Molecular & Clinical Medicine ISSN 2515-8260 Volume 07, Issue 03, 2020 3122 THE ABANDONMENT DEFENSE Dildora Kamalova Tashkent State University of Law, Republic of Uzbekistan Abstract: In this article, the author analysed the role, significance and need for the correct determination of the motive for the pre-crime abandonment based on the analysis of a judgment, and also developed scientific conclusions on this issue. Key words: voluntary renunciation, motivation, volunteering, finality, preparation for crime, criminal attempt, rape, forceful sexual intercourse in unnatural form INTRODUCTION The adoption of the Criminal Code of the Republic of Uzbekistan in 1994 (1994) marked a new stage in the development of the criminal law, which establishes responsibility for the stages of crime. The legislature, after analyzing law enforcement practices, has seriously revised its criminal law provisions. Thus, a new chapter entitled "Incomplete Crimes" was added to the Code. It is noteworthy that for the first time in criminal law the concept of "incomplete crimes" was used. Article 25 of the Criminal Code is called preparation for a crime and attempt to commit a crime, and Article 26 of the Criminal Code is entitled "voluntary return from the commission of a crime", which includes the concept of voluntary return from a crime, its signs and legal consequences. It is crucially and globally important to apply properly criminal law norms in regard inchoate crimes, differentiation of sentencing for preparation of an offence and criminal attempt, individualizing punishment of convicts, properly identify the features of pre-crime abandonment, differ it from inchoate offence and finally rewarding active and good behavior which is aimed at deterring a crime. -

The History of Law and Judicial Proceeding of Pre-Petrine Russia in the Publications of Western European and American Historians (A Review Article)

Journal of Siberian Federal University. Humanities & Social Sciences 4 (2009 2) 538-548 ~ ~ ~ УДК 340 (09) (4|9) The History of Law and Judicial Proceeding of Pre-Petrine Russia in the Publications of Western European and American Historians (a review article) Irina P. Pavlova* Krasnoyarsk State Agrarian University 90 Mira, Krasnoyarsk, 660049 Russia 1 Received 6.11.2009, received in revised form 13.11.2009, accepted 20.11.2009 In the article in the way of common analysis they observe the works of European and American historians-lawyers, dedicated to the Old Russian (pre-Petrine) law (over 60 works). The process of recognition of the Old Russian (Russian) law features had already begun by the Europeans-travelers, and then was continued by scientists-foreigners, who worked in Russia in XVIII-XIX centuries. Author comes to conclusion that the process of scientific mastering of the law and legal procedure history, begun in XX century, was developing steadily, but depended on current political and historical situation, translations and publications of the Russian law relics. Important role of the calling interest to the problem was played by Russian historians-emigrants. The historiography development was going at the line of researching basic specific categories, particular plots of the marking common problems out. To begin with 1980s researching of the Russian law became rather intensive. The articles of those problems was regularly printed in the main journals about questions of the east- European history, appeared monographs. The most actively are used the problems of the state history, anticriminal legislation, court organization, possessions development, serfdom. Author expresses wish that the article materials will help Russian researchers to learn and use the experience of the foreign colleagues more actively. -

KYRGYSTAN Amendment of the Criminal Code of 2 February 2017

12/17/2020 Criminal code of the Kyrgyz Republic Document from CIS Legislation database © 2003-2020 SojuzPravoInform LLC CRIMINAL CODE OF THE KYRGYZ REPUBLIC of February 2, 2017 No. 19 (as amended on 13-11-2020) Accepted by Jogorku Kenesh of the Kyrgyz Republic on December 22, 2016 General part Section I. Penal statute Chapter 1. Penal statute, its purposes and principles Article 1. Penal statute and its purposes 1. The penal statute of the Kyrgyz Republic consists of of this Code based on the Constitution of the Kyrgyz Republic, the conventional principles of international law and regulations, and also the international treaties which came in the procedure established by the law into force whose participant is the Kyrgyz Republic (further - the international agreements). 2. Other legal acts, providing criminal liability for crimes, are subject to application after their inclusion in this Code. 3. The purposes of this Code are protection of the rights and personal freedoms, societies, the states and safety of mankind from criminal encroachments, the prevention of crimes, and also recovery of the justice broken by crime. Article 2. Principle of legality Crime of act and its punishability, and also other criminal consequence in law are determined only by this Code. Article 3. Principle of legal deniteness 1. Legal deniteness means possibility of exact establishment by this Code of the basis for criminal prosecution for crime, and also all signs of actus reus. 2. The penal statute shall determine accurately and clearly punishable offense (action or failure to act) and is not subject to extensive interpretation. 3. -

Legal Russian in Legal - Linguistic Research

Comparative Legilinguistics vol. 32/2017 DOI : http://dx.doi.org/10.14746/cl.2017.32.3 LEGAL RUSSIAN IN LEGAL - LINGUISTIC RESEARCH Marcus GALDIA International University of Monaco [email protected] Abstract: The article focuses upon the emergence and the development of the legal Russian language and the methodology used for its scrutiny in the legal-linguistic research in Russia and abroad. It shows some of the dominant tendencies in the legal-linguistic and related research in a perspective that combines material issues concerning the work on textual sources and their identification as well as methods developed in Russia to deal with legal- linguistic problems. The author aims to portray methodological continuity and discontinuity in a research area with a relatively long history. The overview of topics and methods demonstrates that the development in the area of the legal-linguistic research in Russia displays all characteristic features of the European legal-linguistic tradition, and especially the shift in the attention of scholars from isolated terminological issues to discursive aspects of law. Key words: legal Russian, legal terminology, comparative legal linguistics, legal discourse Marcus GALDIA: Legal Russian in Legal… Streszczenie: Artykuł traktuje o kształtowaniu i rozwoju języka rosyjskiego prawa oraz o metodologii stosowanej w studiach legilingwistycznych w Rosji i za granicą. Autor ilustruje tendencje dominujące w badaniach legilingwistycznych i badaniach zbliżonych do nich koncentrując się na problemach dotyczących identyfikacji -

Crime Preparation Regulation Peculiarities in Criminal Codes of CIS Countries 1Sergej N

DOI 10.29042/2018-3495-3498 Helix Vol. 8(4): 3495- 3498 Crime Preparation Regulation Peculiarities in Criminal Codes of CIS Countries 1Sergej N. Bezugly, 2Viktoriya S. Kirilenko, 3Anzhelika I. Lyahkova, 4Leonid A. Prokhorov 5Oksana S. Stepanyuk 1, 3, 5 Belgorod State University, 85 Pobedy Street, Belgorod, Belgorod Region, 308015, Russia 2 The Institute of Service Sector and Entrepreneurship (Branch) of DSTU in Shakhty, 147 Shevchenko Street, Shakhty, Rostov Oblast, 346500, Russia 4 Kuban State University, 149 Stavropol'skaya St., Krasnodar, Russia Email: [email protected] Received: 16th May 2018, Accepted: 04th June 2018, Published: 30th June 2018 Abstract criminal-legal phenomena, although they are the types The article analyzes the texts of CIS country criminal of an unfinished crime, since they have a different set laws for the completeness of objective and subjective of objective and subjective attributes and entail reflection of crime preparation signs. They revealed different consequences. Proceeding from this, it seems the specifics of methods for objective characteristics reasonable to study the preparation for a crime first. description in the articles of the General Part of the Criminal Law. They studied the legislative approaches Methodology to the limits and the methods of preparatory action The research was based on a dialectical approach to criminalizing. It is stated that with all the diversity of the disclosure of legal phenomena and processes using legislative approaches to objective and subjective general scientific (system, logical, analysis and crime preparation sign formalizing, it is possible to synthesis) and private-scientific methods. The latter single out some common features for all states. -

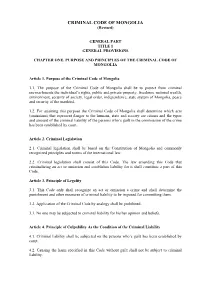

CRIMINAL CODE of MONGOLIA (Revised)

CRIMINAL CODE OF MONGOLIA (Revised) GENERAL PART TITLE 1 GENERAL PROVISIONS CHAPTER ONE. PURPOSE AND PRINCIPLES OF THE CRIMINAL CODE OF MONGOLIA Article 1. Purpose of the Criminal Code of Mongolia 1.1. The purpose of the Criminal Code of Mongolia shall be to protect from criminal encroachments the individual’s rights, public and private property, freedoms, national wealth, environment, security of society, legal order, independence, state system of Mongolia, peace and security of the mankind. 1.2. For attaining this purpose the Criminal Code of Mongolia shall determine which acts (omissions) that represent danger to the humans, state and society are crimes and the types and amount of the criminal liability of the persons who’s guilt in the commission of the crime has been established by court. Article 2. Criminal Legislation 2.1. Criminal legislation shall be based on the Constitution of Mongolia and commonly recognized principles and norms of the international law. 2.2. Criminal legislation shall consist of this Code. The law amending this Code that criminalizing an act or omission and establishes liability for it shall constitute a part of this Code. Article 3. Principle of Legality 3.1. This Code only shall recognize an act or omission a crime and shall determine the punishment and other measures of criminal liability to be imposed for committing them. 3.2. Application of the Criminal Code by analogy shall be prohibited. 3.3. No one may be subjected to criminal liability for his/her opinion and beliefs. Article 4. Principle of Culpability As the Condition of the Criminal Liability 4.1. -

A ROMAN IMPRINT Tatiana Yugay SUMMARY

Iura & Legal Systems - ISSN 2385-2445 2018 C(9): 93-103 LAND PROPERTY RIGHTS THROUGH CENTURIES: A ROMAN IMPRINT Tatiana Yugay SUMMARY: 1. - The Concept of Land Property in the Main Sources of Roman Law; 2. - The Byzantine Influence on Old Russian Law; 3. - Conclusion. 1. - The Concept of Land Property in the Main Sources of Roman Law a) Roman Heritage in the Field of Land Property According to Mcsweeney, the modern legal science owes to Roman lawmakers not only early methodological concepts but the very language of property, which underlies the way we talk about the relationship between people and things in both common law and civil law systems. Property, along with contract and tort, is one of the fundamental divisions of private law in the common law. He presumes, “The language of property actually comes out of a very specific cultural and historical context. It comes from Roman law and canon law, which together formed the medieval ius commune, or common law of Christendom. It was the ius commune, the ancestor of the civil law systems that dominates continental Europe today that gave English its words possession and property”1. Oestereich credits Romans with invention of real property as a result of their practical approach to measuring and documenting land possessions. “The ancient Romans, guided by their predominantly urban (i.e. literally petrified) perspective, on the one hand, and by their ability of and positive experience in keeping written records, on the other hand, started to make land holding a subject of systematic formalization and documentation”. It is worth mentioning that no distinction was made with respect to benefits (‘fruits’), access to them and the soil itself. -

Criminal Law Outline I. Basic Principals

Criminal Law Outline, Spring 2015, Criminal Law Outline I. Basic Principals A Crime is a moral wrong that results in some social harm. A single harm may give rise to both civil and criminal liability. Note OJ Simpson trials. However, there are important points of differentiation between civil and criminal offenses. (1) The Nature of the wrong: Civil there is some loss to the individual. In a criminal case the type of harm in general is a social harm. Really looking at the community in general in criminal harm to social fabric, which affect your sense of security, and thus justify the moral condemnation of the community. (2) The purpose of the legal action: Civil is to compensate loss. Criminal has multiple purposes: punishment, incapacitation, or deterrence. (3) Person brining the suit: The victim brings the suit in the civil case. In a criminal case, it is not the victim, the harm is committed against the people. The criminal system the power to bring a case rests exclusively in the government’s hands. (4) Interests represented in court: The district attorney chooses whether to bring a case or not. (5) The sanction: Criminal 2 types of sanctions: (1) being declared guilty—social stigma; and (2) punishment itself—fine, incarceration, etc. Four Conditions Necessary to have a penalty: 1. The primary addressee who is supposed to conform his conduct to the direction must know: a. Of its existence. b. Of its content in relevant respect. 2. He must know about the circumstances of fact, which make the abstract terms of the direction appropriate in particular instance. -

Artículo Original

http: 10.36097/rsan.v1i44.1591 Artículo Original Abstract The objective of this study was to analyze what was tempted by direct criminal science. A basic investigation is a dialectical approach to the dissemination of legal phenomena and processes, going through gerais scientific methods (systematic and logical methods, analysis and synthesis) and specific scientific methods. The results will show that the attempted crime was part of the objective side of a certain criminal corpus. The beginning of the attempt may coincide as the beginning of the constitutive act of the crime. Furthermore, an attempt is classified by the implementation of the intention as completed and not completed. And, finally, a special kind of attempt is a "futile attempt." An unsuccessful attempt must be subject to responsibility and qualification, bem as a common attempt. Keywords: incipient crime, attempt, futile attempt, preparation for or crime. Resumen El objetivo de este estudio fue analizar qué fue inducido por la ciencia criminal directa. Una investigación básica es un acercamiento dialéctico a la difusión de fenómenos y procesos jurídicos, pasando por métodos científicos generales (métodos sistemáticos y lógicos, análisis y síntesis) y métodos científicos específicos. Los resultados mostrarán que la tentativa de delito fue parte del lado objetivo de un determinado cuerpo criminal. El inicio del intento puede coincidir con el inicio del acto constitutivo del delito. Además, un intento se clasifica según la implementación de la intención como completado y no completado. Y, finalmente, un tipo especial de intento es un "intento inútil". Un intento fallido debe estar sujeto a responsabilidad y calificación, como un intento común. -

Russkaya Pravda and Prince Yaroslav's Statute on Church Courts

Chapter 4 (Yaroslav N. Shchapov) Russkaya Pravda and Prince Yaroslav’s Statute on Church Courts The name of Yaroslav Vladimirovich, the Old Russian Grand Prince of Kiev and Novgorod in the eleventh century, whose memory we revere in connection with the celebration of the anniversary of the city of Ya- roslavl founded by him, is linked with a number of legislative initiatives that have reached us in different forms and traditions. The historical conditions that existed on the territory of Southern and Northern Rus in the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries did not favour the preservation of those princely orders, laws and statutes in the original and undamaged form. All the written texts containing them belong to much later peri- ods, the fourteenth, fifteenth and subsequent centuries and are usually presented by versions (redactions) and copies that included changes and innovations introduced by scribes-editors in order to adopt the ancient legislation to the needs of their time. But it does not diminish the signif- icant contribution of Prince Yaroslav, the Christian legislator and cod- ifier of law, into creation and consolidation of the Old Russian society and state of the eleventh century. The researchers — historians and 239 lawyers — in all probability manage to reconstruct not only the content of ancient monuments, but also their structure and even the text. One of the documents (or some of the documents) linked with the name of Prince Yaroslav is the “charter” of the Prince to which the peo- ple of Novgorod referred in order to substantiate their right to invite a prince to rule or to refuse the recognition of him as a prince.