December 24, 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Voluntary Refusal to Commit a Crime: Significance, General and Special Signs

1884 International Journal of Criminology and Sociology, 2020, 9, 1884-1888 Voluntary Refusal to Commit a Crime: Significance, General and Special Signs Sergej N. Bezugly, Evgenij A. Ignatenko*, Elena F. Lukyanchikova, Oksana S. Shumilina and Natalia Yu. Zhilina Belgorod State University, 85 Pobedy Street, Belgorod, 308015, Russian Federation Abstract: The article describes and examines the significance of the rule of the voluntary refusal to commit a crime, as well as explores its general and special signs. It is noted that the voluntary refusal to commit a crime is the rule contained in any modern, progressive law. In this vein, there are different theoretical approaches to the determination of its value and signs. The signs are debatable in nature, and their establishment by the law enforcer may cause difficulties. The difference between voluntary refusal to commit a crime, which is implemented in three functions, is determined, definitions of general signs of voluntary refusal are proposed, their content is clarified. Special signs of voluntary refusal are disclosed. Keywords: Voluntary refusal to commit a crime, signs of voluntary refusal, stages of a crime, preparation for a crime, attempted crime, criminal liability. INTRODUCTION instance, Greenawalt investigates communications that can lead to antisocial behaviour. Moreover, he Each rule of criminal law has its significance, which concentrates on criminal counselling and vaguer is subject to theoretical understanding. Voluntary advocacy of crime, that is to say, definitions refusal to commit a crime implements several encouraging illegal actions. However, the discussion necessary socially useful, humanistic, economic also covers provocative comments that trigger hostile, functions. violent responses, as well as to disclosures of the reality that supplies incentives to commit crimes or help The issue of signs of voluntary refusal is highly with their commission. -

The Abandonment Defense

European Journal of Molecular & Clinical Medicine ISSN 2515-8260 Volume 07, Issue 03, 2020 3122 THE ABANDONMENT DEFENSE Dildora Kamalova Tashkent State University of Law, Republic of Uzbekistan Abstract: In this article, the author analysed the role, significance and need for the correct determination of the motive for the pre-crime abandonment based on the analysis of a judgment, and also developed scientific conclusions on this issue. Key words: voluntary renunciation, motivation, volunteering, finality, preparation for crime, criminal attempt, rape, forceful sexual intercourse in unnatural form INTRODUCTION The adoption of the Criminal Code of the Republic of Uzbekistan in 1994 (1994) marked a new stage in the development of the criminal law, which establishes responsibility for the stages of crime. The legislature, after analyzing law enforcement practices, has seriously revised its criminal law provisions. Thus, a new chapter entitled "Incomplete Crimes" was added to the Code. It is noteworthy that for the first time in criminal law the concept of "incomplete crimes" was used. Article 25 of the Criminal Code is called preparation for a crime and attempt to commit a crime, and Article 26 of the Criminal Code is entitled "voluntary return from the commission of a crime", which includes the concept of voluntary return from a crime, its signs and legal consequences. It is crucially and globally important to apply properly criminal law norms in regard inchoate crimes, differentiation of sentencing for preparation of an offence and criminal attempt, individualizing punishment of convicts, properly identify the features of pre-crime abandonment, differ it from inchoate offence and finally rewarding active and good behavior which is aimed at deterring a crime. -

KYRGYSTAN Amendment of the Criminal Code of 2 February 2017

12/17/2020 Criminal code of the Kyrgyz Republic Document from CIS Legislation database © 2003-2020 SojuzPravoInform LLC CRIMINAL CODE OF THE KYRGYZ REPUBLIC of February 2, 2017 No. 19 (as amended on 13-11-2020) Accepted by Jogorku Kenesh of the Kyrgyz Republic on December 22, 2016 General part Section I. Penal statute Chapter 1. Penal statute, its purposes and principles Article 1. Penal statute and its purposes 1. The penal statute of the Kyrgyz Republic consists of of this Code based on the Constitution of the Kyrgyz Republic, the conventional principles of international law and regulations, and also the international treaties which came in the procedure established by the law into force whose participant is the Kyrgyz Republic (further - the international agreements). 2. Other legal acts, providing criminal liability for crimes, are subject to application after their inclusion in this Code. 3. The purposes of this Code are protection of the rights and personal freedoms, societies, the states and safety of mankind from criminal encroachments, the prevention of crimes, and also recovery of the justice broken by crime. Article 2. Principle of legality Crime of act and its punishability, and also other criminal consequence in law are determined only by this Code. Article 3. Principle of legal deniteness 1. Legal deniteness means possibility of exact establishment by this Code of the basis for criminal prosecution for crime, and also all signs of actus reus. 2. The penal statute shall determine accurately and clearly punishable offense (action or failure to act) and is not subject to extensive interpretation. 3. -

Crime Preparation Regulation Peculiarities in Criminal Codes of CIS Countries 1Sergej N

DOI 10.29042/2018-3495-3498 Helix Vol. 8(4): 3495- 3498 Crime Preparation Regulation Peculiarities in Criminal Codes of CIS Countries 1Sergej N. Bezugly, 2Viktoriya S. Kirilenko, 3Anzhelika I. Lyahkova, 4Leonid A. Prokhorov 5Oksana S. Stepanyuk 1, 3, 5 Belgorod State University, 85 Pobedy Street, Belgorod, Belgorod Region, 308015, Russia 2 The Institute of Service Sector and Entrepreneurship (Branch) of DSTU in Shakhty, 147 Shevchenko Street, Shakhty, Rostov Oblast, 346500, Russia 4 Kuban State University, 149 Stavropol'skaya St., Krasnodar, Russia Email: [email protected] Received: 16th May 2018, Accepted: 04th June 2018, Published: 30th June 2018 Abstract criminal-legal phenomena, although they are the types The article analyzes the texts of CIS country criminal of an unfinished crime, since they have a different set laws for the completeness of objective and subjective of objective and subjective attributes and entail reflection of crime preparation signs. They revealed different consequences. Proceeding from this, it seems the specifics of methods for objective characteristics reasonable to study the preparation for a crime first. description in the articles of the General Part of the Criminal Law. They studied the legislative approaches Methodology to the limits and the methods of preparatory action The research was based on a dialectical approach to criminalizing. It is stated that with all the diversity of the disclosure of legal phenomena and processes using legislative approaches to objective and subjective general scientific (system, logical, analysis and crime preparation sign formalizing, it is possible to synthesis) and private-scientific methods. The latter single out some common features for all states. -

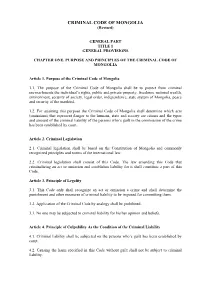

CRIMINAL CODE of MONGOLIA (Revised)

CRIMINAL CODE OF MONGOLIA (Revised) GENERAL PART TITLE 1 GENERAL PROVISIONS CHAPTER ONE. PURPOSE AND PRINCIPLES OF THE CRIMINAL CODE OF MONGOLIA Article 1. Purpose of the Criminal Code of Mongolia 1.1. The purpose of the Criminal Code of Mongolia shall be to protect from criminal encroachments the individual’s rights, public and private property, freedoms, national wealth, environment, security of society, legal order, independence, state system of Mongolia, peace and security of the mankind. 1.2. For attaining this purpose the Criminal Code of Mongolia shall determine which acts (omissions) that represent danger to the humans, state and society are crimes and the types and amount of the criminal liability of the persons who’s guilt in the commission of the crime has been established by court. Article 2. Criminal Legislation 2.1. Criminal legislation shall be based on the Constitution of Mongolia and commonly recognized principles and norms of the international law. 2.2. Criminal legislation shall consist of this Code. The law amending this Code that criminalizing an act or omission and establishes liability for it shall constitute a part of this Code. Article 3. Principle of Legality 3.1. This Code only shall recognize an act or omission a crime and shall determine the punishment and other measures of criminal liability to be imposed for committing them. 3.2. Application of the Criminal Code by analogy shall be prohibited. 3.3. No one may be subjected to criminal liability for his/her opinion and beliefs. Article 4. Principle of Culpability As the Condition of the Criminal Liability 4.1. -

Criminal Law Outline I. Basic Principals

Criminal Law Outline, Spring 2015, Criminal Law Outline I. Basic Principals A Crime is a moral wrong that results in some social harm. A single harm may give rise to both civil and criminal liability. Note OJ Simpson trials. However, there are important points of differentiation between civil and criminal offenses. (1) The Nature of the wrong: Civil there is some loss to the individual. In a criminal case the type of harm in general is a social harm. Really looking at the community in general in criminal harm to social fabric, which affect your sense of security, and thus justify the moral condemnation of the community. (2) The purpose of the legal action: Civil is to compensate loss. Criminal has multiple purposes: punishment, incapacitation, or deterrence. (3) Person brining the suit: The victim brings the suit in the civil case. In a criminal case, it is not the victim, the harm is committed against the people. The criminal system the power to bring a case rests exclusively in the government’s hands. (4) Interests represented in court: The district attorney chooses whether to bring a case or not. (5) The sanction: Criminal 2 types of sanctions: (1) being declared guilty—social stigma; and (2) punishment itself—fine, incarceration, etc. Four Conditions Necessary to have a penalty: 1. The primary addressee who is supposed to conform his conduct to the direction must know: a. Of its existence. b. Of its content in relevant respect. 2. He must know about the circumstances of fact, which make the abstract terms of the direction appropriate in particular instance. -

Artículo Original

http: 10.36097/rsan.v1i44.1591 Artículo Original Abstract The objective of this study was to analyze what was tempted by direct criminal science. A basic investigation is a dialectical approach to the dissemination of legal phenomena and processes, going through gerais scientific methods (systematic and logical methods, analysis and synthesis) and specific scientific methods. The results will show that the attempted crime was part of the objective side of a certain criminal corpus. The beginning of the attempt may coincide as the beginning of the constitutive act of the crime. Furthermore, an attempt is classified by the implementation of the intention as completed and not completed. And, finally, a special kind of attempt is a "futile attempt." An unsuccessful attempt must be subject to responsibility and qualification, bem as a common attempt. Keywords: incipient crime, attempt, futile attempt, preparation for or crime. Resumen El objetivo de este estudio fue analizar qué fue inducido por la ciencia criminal directa. Una investigación básica es un acercamiento dialéctico a la difusión de fenómenos y procesos jurídicos, pasando por métodos científicos generales (métodos sistemáticos y lógicos, análisis y síntesis) y métodos científicos específicos. Los resultados mostrarán que la tentativa de delito fue parte del lado objetivo de un determinado cuerpo criminal. El inicio del intento puede coincidir con el inicio del acto constitutivo del delito. Además, un intento se clasifica según la implementación de la intención como completado y no completado. Y, finalmente, un tipo especial de intento es un "intento inútil". Un intento fallido debe estar sujeto a responsabilidad y calificación, como un intento común. -

Accountability Issues "

Summary The year: 2020. Specialty / field of study (code and full name): 40.03.01-Law Level of study: bachelor's degree. Institute or Higher school: Law University. Department of criminal law disciplines and forensic expertise The subject of the final qualifying work::"Crime Preparation: Qualification and Accountability Issues ". Author: Stepanchenko Rodion Sergeevich, 4th year student Institute of distance learning, information technology and online projects (Criminal law profile) - 341-16. Scientific supervisor: kand.yus. sciences, associate professor, head of the Department of Criminal Law Disciplines and Forensic Expertise Yury Nikolayevich Shapovalov. The relevance of the research topic.In recent years, the problem of crime has acquired special significance for Russian society. Its widespread rampant became a genuine social disaster for our country. The implementation of the objectives of the criminal law formulated in Art. 2 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation (hereinafter - the Criminal Code, the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation) on the protection of human and civil rights and freedoms, property, public order and public safety, the environment, the constitutional system of the Russian Federation against criminal attacks, on ensuring peace and security of humanity, for the prevention of crime involves the determination on the basis of the law of the circle of criminal attacks. And immediately the question arises of the extent to which acts are recognized criminal and punishable for preparations for a crime, aimed at creating the conditions for their commission, but interrupted due to circumstances beyond the control of a person. A necessary sign of preparation as a type of unfinished criminal activity under the current legislation (Article 14 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation) is the public danger of its actions. -

THE INTERNET and TERRORISM EXPRESSION CRIME WHERE IS the NEW BOUNDARY? Diritto Penale (IUS/17)

UNIVERSITA’ DEGLI STUDI DI MILANO Dipartimento di Scienze Giuridiche “C. Beccaria” Dottorato di ricerca di Scienze Giuridiche "Cesare Beccaria" Curriculum Diritto Penale e Processuale Penale XXXI ciclo THE INTERNET AND TERRORISM EXPRESSION CRIME WHERE IS THE NEW BOUNDARY? Diritto penale (IUS/17) Relatore: Prof. Gian Luigi Gatta Correlatore: Prof. Francesco Viganò Tesi di Laurea di: Yan DONG Matr. R11316 Anno Accademico 2018/2019 Abstract The main purpose of this thesis is to figure out the new boundary of terrorism expression crime in the internet age. Before answering this question, it provided the empirical evidence of how terrorists are radicalized by the terrorism propaganda online and proposed a new theoretical framework to explain this phenomenon. Accordingly, how the legal framework evolved during the past years to combat this phenomenon was reviewed. By comparing the national laws and typical boundary cases in the Supreme Court of the US, the UK and Italy, it finally proposed some suggestions for Chinese criminal justice system to find a balancing roadmap in terms of combating modern terrorism expression offenses while protecting freedom of expression, taking considerations of the constitutional context in different countries. October 2018 Milan 1 1. Introduction ···································································································································· 4 2. The role of Internet and modern terrorism ····················································································· 5 -

Journal of Law

Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University Faculty of Law Journal of Law #2, 2012 UDC(uak) 34(051.2) s-216 Editor-in-Chief Besarion Zoidze (Prof., TSU) Editorial Board: Levan Alexidze (Prof.,TSU) Giorgi Davitashivili (Prof., TSU) Avtandil Demetrashvili (Prof.,TSU) Mzia Lekveishvili (Prof., TSU) Guram Nachkebia (Prof., TSU) Tevdore Ninidze (Prof., TSU) Nugzar Surguladze (Prof.,TSU) Lado Chanturia (Prof., TSU) Giorgi Khubua (Prof.) Lasha Bregvadze (T. Tsereteli Institute of State and Law, Director) Irakli Burduli (Prof.,TSU) Paata Turava (Prof.) Gunther Teubner (Prof., Frankfurt University) Lawrence Friedman (Prof., Stanford University) Bernd Schünemann (Prof., Munich University) Peter Häberle (Prof., Bayreuth University) © Tbilisi University Press, 2013 ISSN 2233-3746 Table of Contents Elza Chachanidze Accusation of a Crime against Property…………………………………..…………………………….5 Lela Janashvili The State of Autonomies and the Nation of Nations (Historical Preconditions and Perspectives ……………………………………………………...…….15 Lana Tsanava Regionalism as the Form of Territorial Organization of the State ……………………………………31 Tamar Gvaramadze Sanctions for Tax Code Violations …………………………………..………………………………..48 Sergi Jorbenadze Order of the President of Georgia as the Data Containing Privacy …………………………………...67 Jaba Usenashvili Problem of Realisation of Right for Privacy In the Process of Implementation of Operative-search Measures Controlled by the Court ……….…77 Koba Kalichava Strategic Aspects of Improving Ecological Legislation ……………………………………………..102 Giorgi Makharoblishvili -

Country Review Report of Ukraine

Country Review Report of Ukraine Review by Slovenia and Poland of the implementation by Ukraine of articles 15 – 42 of Chapter III. “Criminalization and law enforcement” and articles 44 – 50 of Chapter IV. “International cooperation” of the United Nations Convention against Corruption for the review cycle 2010 - 2015 1 Introduction The Conference of the States Parties to the United Nations Convention against Corruption was established pursuant to article 63 of the Convention to, inter alia, promote and review the implementation of the Convention. In accordance with article 63, paragraph 7, of the Convention, the Conference established at its third session, held in Doha from 9 to 13 November 2009, the Mechanism for the Review of Implementation of the Convention. The Mechanism was established also pursuant to article 4, paragraph 1, of the Convention, which states that States parties shall carry out their obligations under the Convention in a manner consistent with the principles of sovereign equality and territorial integrity of States and of non-intervention in the domestic affairs of other States. The Review Mechanism is an intergovernmental process whose overall goal is to assist States parties in implementing the Convention. The review process is based on the terms of reference of the Review Mechanism. Process The following review of the implementation by Ukraine of the Convention is based on the completed response to the comprehensive self-assessment checklist received from Ukraine, and any supplementary information provided in accordance with paragraph 27 of the terms of reference of the Review Mechanism and the outcome of the constructive dialogue between the governmental experts from Poland and Slovenia, by means of telephone conferences, e-mail exchanges, trilateral meetings or other means of active dialogue in accordance with the terms of reference of the Review Mechanism, and involving the following experts from the reviewing States: Poland Ms. -

An Old Crime in a New Context: Maryland’S Need for a Comprehensive Cyberstalking Statute Christie Chung

University of Maryland Law Journal of Race, Religion, Gender and Class Volume 17 | Issue 1 Article 8 An Old Crime in a New Context: Maryland’s Need for a Comprehensive Cyberstalking Statute Christie Chung Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/rrgc Recommended Citation Christie Chung, An Old Crime in a New Context: Maryland’s Need for a Comprehensive Cyberstalking Statute, 17 U. Md. L.J. Race Relig. Gender & Class 117 (2017). Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/rrgc/vol17/iss1/8 This Notes & Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Journals at DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Maryland Law Journal of Race, Religion, Gender and Class by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Chung AN OLD CRIME IN A NEW CONTEXT: MARYLAND’S NEED FOR A COMPREHENSIVE CYBERSTALKING STATUTE Christie Chung* INTRODUCTION The Department of Justice defines stalking as a “pattern of repeated and unwanted attention, harassment, contact, or any other course of conduct directed at a specific person that would cause a reasonable person to feel fear.”1 Unlike a multitude of other crimes, stalking is unique in that it is a composite offense made up of a pattern of, oftentimes, varied behaviors.2 These behaviors include, but are by no means limited to: direct and indirect threats of harm, following or lying in wait for the victim at their home, place of work, and other frequented locales, and sending unwanted gifts and items.3 Although the first anti-stalking statute was not passed until 1990, rapid technological advances in the intervening decades have entirely redefined the scope of the offense.4 As a “borderless medium” that provides a veneer of anonymity, the internet has proven to be a fertile landscape of new opportunity for those looking to stalk, harass, or otherwise attack others.5 Cyberstalking, as a subset of computer- © 2017 Christie Chung * J.D.