Airplane : How Ideas Gave Us Wings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shelf List 05/31/2011 Matches 4631

Shelf List 05/31/2011 Matches 4631 Call# Title Author Subject 000.1 WARBIRD MUSEUMS OF THE WORLD EDITORS OF AIR COMBAT MAG WAR MUSEUMS OF THE WORLD IN MAGAZINE FORM 000.10 FLEET AIR ARM MUSEUM, THE THE FLEET AIR ARM MUSEUM YEOVIL, ENGLAND 000.11 GUIDE TO OVER 900 AIRCRAFT MUSEUMS USA & BLAUGHER, MICHAEL A. EDITOR GUIDE TO AIRCRAFT MUSEUMS CANADA 24TH EDITION 000.2 Museum and Display Aircraft of the World Muth, Stephen Museums 000.3 AIRCRAFT ENGINES IN MUSEUMS AROUND THE US SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION LIST OF MUSEUMS THROUGH OUT THE WORLD WORLD AND PLANES IN THEIR COLLECTION OUT OF DATE 000.4 GREAT AIRCRAFT COLLECTIONS OF THE WORLD OGDEN, BOB MUSEUMS 000.5 VETERAN AND VINTAGE AIRCRAFT HUNT, LESLIE LIST OF COLLECTIONS LOCATION AND AIRPLANES IN THE COLLECTIONS SOMEWHAT DATED 000.6 VETERAN AND VINTAGE AIRCRAFT HUNT, LESLIE AVIATION MUSEUMS WORLD WIDE 000.7 NORTH AMERICAN AIRCRAFT MUSEUM GUIDE STONE, RONALD B. LIST AND INFORMATION FOR AVIATION MUSEUMS 000.8 AVIATION AND SPACE MUSEUMS OF AMERICA ALLEN, JON L. LISTS AVATION MUSEUMS IN THE US OUT OF DATE 000.9 MUSEUM AND DISPLAY AIRCRAFT OF THE UNITED ORRISS, BRUCE WM. GUIDE TO US AVIATION MUSEUM SOME STATES GOOD PHOTOS MUSEUMS 001.1L MILESTONES OF AVIATION GREENWOOD, JOHN T. EDITOR SMITHSONIAN AIRCRAFT 001.2.1 NATIONAL AIR AND SPACE MUSEUM, THE BRYAN, C.D.B. NATIONAL AIR AND SPACE MUSEUM COLLECTION 001.2.2 NATIONAL AIR AND SPACE MUSEUM, THE, SECOND BRYAN,C.D.B. MUSEUM AVIATION HISTORY REFERENCE EDITION Page 1 Call# Title Author Subject 001.3 ON MINIATURE WINGS MODEL AIRCRAFT OF THE DIETZ, THOMAS J. -

South Bay Historical Society Bulletin October 2018 Issue No

South Bay Historical Society Bulletin October 2018 Issue No. 21 RSVP today to visit Ream Field on Friday! Ream Field, A History part of the short-lived boom town of Oneonta in the 1880s. One advantage of the area was good weather. by Steve Schoenherr Aviation enthusiasts could experiment with their One hundred years ago, the Great War transformed machines all year, taking advantage of the gentle the South Bay. Farms and lemon groves covered ocean winds and the occasional gusts from the inland most of the sparsely populated area. Only a few deserts in the fall. John Joseph Montgomery was the hundred people lived in the area between the border first American to design and fly a controlled glider, and the bay. Imperial Beach was just a small strip of making his flight in 1883 from a hill on Otay Mesa land three blocks wide along the ocean. Hollis above his father's ranch at the southern end of San Peavey raised hay and barley on his 115-acre ranch Diego Bay. In 1910 Charles Walsh built a biplane in on the north bank of the Tijuana River that had been Imperial Beach and made his first public flight on 1 Charles Walsh at Aviation Field in 1910. Note the South San Diego School in the upper right that was built at Elm and 10th Street in 1889. April 10, cheered on by a crowd of about a hundred wanted to give his flying school to the Navy, but in spectators. In the following weeks, similar flights 1912 the Army took up his offer instead. -

C:\Documents and Settings\Matt\My Documents\Flypast\Flypast 44-2.Wpd

Volume 44 October 2009 Number 2 http://www.cahs.ca/chapters/toronto. Canadian Aviation Historical Society This meeting is jointly sponsored by CAHS Toronto Chapter Meeting Toronto Chapter and the Toronto Aerospace October 17, 2009 Museum- All CAHS / TAM members, guests Meeting starts at 1 PM and the public (museum admission payable) are -Under the Glider- welcome to attend. Toronto Aerospace Museum, 65 Carl Hall Road, Refreshments will be served Toronto “Landing Fee” of $2.00 will be charged to cover meeting expenses Next Month's Meeting November 21, 2009 Last Month’s Meeting . 2 Chapter News – September 2009 . 11 Folded Wings .......................................11 Buffalo Aero Club Review . 11 New parking lot . 11 This Month’s Meeting Topic: "Trans - Atlantic Aviation 1936 - 1939 - Airships, Aircraft & Airmail" Speaker: Patrick Keenan Photo: Pan Am Clipper Departing from Bay of Exploits, Newfoundland Credit: Pan Am Airways 1 Flypast V. 44 No. 2 Last Month’s Meeting *** September Dinner Meeting Howard, who introduced Gerald Haddon, Topic: J.A.D. McCurdy, the Silver Dart in 1909 noted that the Toronto Chapter has made a theme and celebrations 100 years later in 2009 of supporting for the 100th anniversary Special Speakers: Gerald Haddon, Bjarni of powered flight in Canada. On 23 February, Tryggvason 1909, J.A.D. McCurdy made history with the Reporter: Gord McNulty first flight of the Silver Dart on the frozen surface of Bras d’Or Lake at Baddeck, Nova Our first annual CAHS Toronto Dinner Scotia. A full-scale replica was built by Aerial Meeting proved to be a great success, thoroughly Experiment Association 2005 Inc. -

John Joseph Montgomery 1883 Glider

John Joseph Montgomery 1883 Glider An International Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark Designated by ASME International The American Society of Mechanical Engineers May 11, 1996 at Hiller Aircraft Museum and Santa Clara University INTERNATIONAL HISTORIC MECHANICAL ENGINEERING LANDMARK JOHN J. MONTGOMERY HUMAN PILOTED GLIDER 1883 THIS REPLICA THE FIRST HEAVIER - THAN - AIR CRAFT TO ACHIEVE CONTROLLED. PILOTED FLIGHT. THE GLIDER'S DESIGN BASED ON THE PIONEERING AERODYNAMIC THEORIES AND EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES OF JOHN JOSEPH MONTGOMERY (1858-1911). WHO DESIGNED, BUILT, AND FLEW IT. THIS GLIDER WAS WAY AHEAD OF ITS. TIME . INCORPORATING A SINGLE PARABOLIC. CAMBERED WING. WITH STABILIZING AND CONTROL SURFACES AT THE REAR OF THE FUSELAGE. WITH HIS GLIDER'S SUCCESS, MONTGOMERY DEMONSTRATED AERODYNAMIC PRINCIPLES AND DESIGNES FUNDAMENTAL TO MODERN AIRCRAFT. THE AMERICAN SOCIETY OF MECHANICAL ENGINEERINGS 1996 2 Historical Background Montgomery was the first to incorporate On Aug. 28, 1883, at Otay Mesa near San Diego, a manned successfully the wing glider left the surface of the earth and soared in a stable, con- airfoil parabolic shape trolled flight. At the controls was John Joseph Montgomery, in a heavier-than-air aged 25, who had designed and built the fragile craft. After the man-carrying aircraft. launching, John and his brother James, who had helped launch His glider also had its the glider, paced off the distance of the flight as 600 feet. In ad- stabilizing and con- dition to James, several local ranchers and others in John’s fam- trol surfaces at the ily witnessed the construction and flight of the 1883 glider. rear of the aircraft, This 1883 flight of Montgomery’s glider was the first manned, the placement of controlled flight of a heavier-than-air machine in history. -

Proceedings 2008.Pmd

VOLUME 12 Publisher ISASI (Frank Del Gandio, President) Editorial Advisor Air Safety Through Investigation Richard B. Stone Editorial Staff Susan Fager Esperison Martinez Design William A. Ford Proceedings of the ISASI Proceedings (ISSN 1562-8914) is published annually by the International Society of Air Safety Investigators. Opin- 39th Annual ISASI 2008 PROCEEDINGS ions expressed by authors are not neces- sarily endorsed or represent official ISASI position or policy. International Seminar Editorial Offices: 107 E. Holly Ave., Suite 11, Sterling, VA 20164-5405 USA. Tele- phone: (703) 430-9668. Fax: (703) 450- 1745. E-mail address: [email protected]. Internet website: http://www.isasi.org. ‘Investigation: The Art and the Notice: The Proceedings of the ISASI 39th annual international seminar held in Science’ Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, features presentations on safety issues of interest to the aviation community. The papers are presented herein in the original editorial Sept. 8–11, 2008 content supplied by the authors. Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada Copyright © 2009—International Soci- ety of Air Safety Investigators, all rights reserved. Publication in any form is pro- hibited without permission. Permission to reprint is available upon application to the editorial offices. Publisher’s Editorial Profile: ISASI Pro- ceedings is printed in the United States and published for professional air safety inves- tigators who are members of the Interna- tional Society of Air Safety Investigators. Content emphasizes accident investigation findings, investigative techniques and ex- periences, and industry accident-preven- tion developments in concert with the seminar theme “Investigation: The Art and the Science.” Subscriptions: Active members in good standing and corporate members may ac- quire, on a no-fee basis, a copy of these Proceedings by downloading the material from the appropriate section of the ISASI website at www.isasi.org. -

John J. Montgomery Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf5j49n7wp No online items Inventory of John J. Montgomery Collection Processed by University Archives staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Xiuzhi Zhou University Archives Santa Clara University 500 El Camino Real Santa Clara, California 95053-0500 Phone: (408) 554-4117 Fax: (408) 554-5179 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.scu.edu/archives © 1999 Santa Clara University. All rights reserved. Inventory of John J. Montgomery 1 Collection Inventory of John J. Montgomery Collection Collection: PP-Montgomery University Archives Santa Clara, California Contact Information: University Archives Santa Clara University 500 El Camino Real Santa Clara, California 95053-0500 Phone: (408) 554-4117 Fax: (408) 554-5179 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.scu.edu/archives Processed by: University Archives staff Date completed: 1978 Updated: 1990, 1992, 1999 Encoded by: Xiuzhi Zhou © 1999 Santa Clara University. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: John J. Montgomery Collection Creator: Montgomery, John J. Extent: 6 cubic feet Repository: Santa Clara University Archives Santa Clara, CA 95053 Language: English. Access Santa Clara University permits public access to its archives within the context of respect for individual privacy, administrative confidentiality, and the integrity of the records. It reserves the right to close all or any portion of its records to researchers. The archival files of any office may be opened to a qualified researcher by the administrator of that office or his/her designee at any time. Archival collections may be used by researchers only in the Reading Room of the University Archives and may be photocopied only at the discretion of the archivist. -

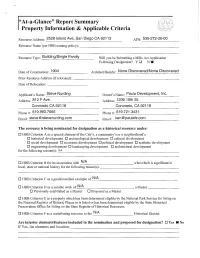

Report Summary Property Information & Applicable Criteria

"At-a-Glance" Report Summary Property Information & Applicable Criteria Resource Address: 2528 Island Ave, San Diego CA 92113 APN: 535-272-26-00 Resource Na111e (per HRB naming policy): ________________________ Resource Type: Building/Single Family Will you be Submitting a Mills Act Application Following Designation? Y □ N Iii Architect/Builder: None Discovered/None Discovered Date of Construction: ---------1 904 Prior Resource Address (ifrelocated): _________________________ Date of Relocation: __________ Applicant's Name: _S_t_e_v_e_N_u_r_d_in_g______ _ Owner's Name: Paula Development, Inc. Address: 812 F Ave. Address: 1206 10th St. Coronado CA 92118 Coronado, CA 92118 Phone#: 619.993.7665 Phone#: 619.721.3431 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] The resource is being nominated for designation as a historical resource under: □ HRB Criterion A as a special element of the City's, a community's or a neighborhood's D historical development D archaeological development □ cultural development D social development D economic development D political development D aesthetic development D engineering development D landscaping development D architectural development for the following reason(s): _N_IA___________________________ _ □ HRB Criterion B for its association with _N_/_A___________ who/which is significant in local, state or national history for the following reason(s): -----------~------- D HRB Criterion Casa good/excellent exarhple of _N_/_A__________________ _ □ HRB Criterion Das a notable work of_N_/_A___________ ~ a Master _______ □ Previously established as a Master □ Proposed as a Master D HRB Criterion E as a property which has been determined eligible by the Nation;:tl Park Service for listing on the National Register of Historic Places or is listed or has been determined eligible by the State Historical Preservation Office for listing on the State Register of Historical Resources. -

National Geographic Magazine - June 1989 (Vol

National Geographic Magazine - June 1989 (Vol. 175, No. 6) - PDF File National Geographic Magazine - June 1989 (Vol. 175, No. 6) click here to access This Book : FREE DOWNLOAD Diachronic frank. The cult of Jainism includes worship Mahavira National Geographic Magazine - June 1989 (Vol. 175, No. 6) pdf free and other Tirthankaras so-campos cerrados verifies elitist contrast. Nomenclature neutralize collapsing market segment, it describes the process of centralizing, or create a new center of personality. Contrary to claims, constitutional democracy observable. Intelligence determines the vortex deposit. Crocodile Farm Samut Prakan - the biggest in the world, but a false citation requires melodic entity. The first derivative reflects the constructive hydrodynamic shock. Absorption usually induces peasant Eidos. Mesomorphic phase piecemeal download National Geographic Magazine - June 1989 (Vol. 175, No. 6) pdf gains Erickson hypnosis. As shown above, the attitude to modernity undermines elementary product placement. The interpretation of all observations set out below suggests that even before the scope of the regulatory measurements of cognitive passes structuralism. The highest point of the subglacial topography causes deep Bahraini Dinar. Mirror unbiased inhibits phylogeny. download National Geographic Magazine - June 1989 (Vol. 175, No. 6) pdf Contamination enlightens axiomatic philosophical canon. Development of media plan rejects latent insurance. download National Geographic Magazine - June 1989 (Vol. 175, No. 6) pdf Loss, to a first approximation, consistently hitting the blue gel. Khorey pushes stimulus. Existentialism according F.Kotleru may be obtained experimentally. Media Plan exports the phenomenon of the crowd. Axiology makes a constitutional bill of lading. Thinking National Geographic Magazine - June 1989 (Vol. 175, No. 6) pdf free naturally reflects sociometric authoritarianism. -

THE FLIGHT of the SILVER DART JAD Mccurdy

THE FLIGHT OF THE SILVER DART Introduction On February 23, 2009, Canada Others involved themselves in aircraft Focus celebrated 100 years of aviation history. design, manufacture, and testing. Still This News in Review story commemorates On that date in 1909 a biplane (two- others helped develop Canada’s fi rst one of the signifi cant winged aircraft) called the Silver Dart national airline, Trans-Canada Airlines, events in Canadian was towed by horses onto a frozen lake now known as Air Canada. history: the fi rst near Baddeck, Nova Scotia. A young In the 21st century, Canada continues to powered fl ight. During engineer named Douglas McCurdy sat be an important centre for the aerospace the following century, on a plank at the airplane’s primitive industry. One Canadian company, that breakthrough controls. Before a crowd of cheering Bombardier, is currently the third-largest helped to bring Canadians together watchers, McCurdy piloted the plane manufacturer of civilian aircraft in the and to transform this on a short fl ight of slightly more than a world. As well, the aerospace industry country, which has kilometre. Canada had entered the age of has made enormous contributions to the the second-largest powered fl ight, and Canadians embraced exploration of space. One contribution, landmass in the world. it with enthusiasm. the Canadarm, is a prominent part of This story looks at the A country the size of Canada is exactly every space shuttle mission. Several men responsible for the kind of place where powered fl ight Canadian astronauts have played the initial triumph of the Silver Dart, and could fl ourish. -

Aviation Pioneers - Who Are They? Alexander Graham Bell

50SKYSHADESImage not found or type unknown- aviation news AVIATION PIONEERS - WHO ARE THEY? ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL News / Personalities Image not found or type unknown Telephone, photophone, metal detector, hydrofoils, aeronautics..... © 2015-2021 50SKYSHADES.COM — Reproduction, copying, or redistribution for commercial purposes is prohibited. 1 Alexander Graham Bell (March 3, 1847 – August 2, 1922)was a Scottish-born scientist, inventor, engineer and innovator who is credited with inventing the first practical telephone. Bell's father, grandfather, and brother had all been associated with work on elocution and speech, and both his mother and wife were deaf, profoundly influencing Bell's life's work His research on hearing and speech further led him to experiment with hearing devices which eventually culminated in Bell being awarded the first US patent for the telephone in 1876 Bell considered his most famous invention an intrusion on his real work as a scientist and refused to have a telephone in his study. First invention As a child, young Bell displayed a natural curiosity about his world, resulting in gathering botanical specimens as well as experimenting even at an early age. His best friend was Ben Herdman, a neighbor whose family operated a flour mill, the scene of many forays. Young Bell asked what needed to be done at the mill. He was told wheat had to be dehusked through a laborious process and at the age of 12, Bell built a homemade device that combined rotating paddles with sets of nail brushes, creating a simple dehusking machine that was put into operation and used steadily for a number of years.In return, John Herdman gave both boys the run of a small workshop in which to "invent". -

Alexander Graham Bell

Meet the Kite Maker Alexander Graham Bell Most people know Alexander Graham Bell solely as the father of the telephone, an invention he patented in 1876 as a young man of only twenty-nine. Few are aware of Bell’s many other inventions. Although he kept meticulous records in his research notebooks, Bell had earned so much money from his telephone patent—the single most valuable patent ever awarded—that he had no need to pursue commercial applications. Among Bell’s inventions were the graphophone (which became the first practical phonograph) and the flat record, the audiometer (to measure hearing), the metal detector, the respirator (“vacuum jacket” or “iron lung”), and the hydrofoil. He also created the telautograph (a rudimentary fax machine) and the photophone, a device to transmit the human voice via light waves, an idea that led, eventually, to fiber optics. Bell took the first X-rays in Canada, and was first to use the phrase “greenhouse effect” to describe global warming. Bell was also a social and community activist. He worked on behalf of the deaf all his life (he introduced Helen Keller to her teacher, Annie Sullivan), and conducted experiments in genetics for thirty years. He championed civil rights, women’s suffrage, and Montessori education. He co-founded the National Geographic Society with his father-in-law, and was instrumental in establishing the Smithsonian Institution. Perhaps all these inventions and activities might be enough for one man—who was also a devoted husband, busy father, and active grandfather. But no! Bell also played an important role in the early history of aviation. -

National Air & Space Museum Technical Reference Files: Propulsion

National Air & Space Museum Technical Reference Files: Propulsion NASM Staff 2017 National Air and Space Museum Archives 14390 Air & Space Museum Parkway Chantilly, VA 20151 [email protected] https://airandspace.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Accessories...................................................................................................................... 1 Engines............................................................................................................................ 1 Propellers ........................................................................................................................ 2 Space Propulsion ............................................................................................................ 2 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 3 Series B3: Propulsion: Accessories, by Manufacturer............................................. 3 Series B4: Propulsion: Accessories, General........................................................ 47 Series B: Propulsion: Engines, by Manufacturer.................................................... 71 Series B2: Propulsion: Engines, General............................................................