Common Thread Maighread Tobin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

01/02/19 Applications Granted

DATE : 06/02/2019 LIMERICK CITY AND COUNTY COUNCIL TIME : 16:40:42 PAGE : 1 P L A N N I N G A P P L I C A T I O N S PLANNING APPLICATIONS GRANTED FROM 28/01/2019 TO 01/02/2019 in deciding a planning application the planning authority, in accordance with section 34(3) of the Act, has had regard to submissions or observations recieved in accordance with these Regulations; The use of the personal details of planning applicants, including for marketing purposes, maybe unlawful under the Data Protection Acts 1988 - 2003 and may result in action by the Data Protection Commissioner, against the sender, including prosecution. FILE APP. DATE M.O. M.O. NUMBER APPLICANTS NAME TYPE RECEIVED DEVELOPMENT DESCRIPTION AND LOCATION DATE NUMBER 18/516 Brian & Olive O'Brien R 25/05/2018 the construction of a single storey extension to the 30/01/2019 103/2019 southern gable end of the existing dwelling house Roxboro, Ballyclough, Co. Limerick. 18/781 Michael Davis P 02/08/2018 a two storey extension to the side of the existing dwelling 29/01/2019 90/2019 and a single storey extension to the rear together with the conversion of the attic to habitable space and all associated site works 28 Greenhills Road, Garryowen, Limerick. 18/940 Kieran O'Brien P 27/09/2018 a two storey dwelling house, with attached carport, 30/01/2019 104/2019 garage, on site treatment system and percolation area and associated site works Dereen, Kildimo, Co. Limerick. 18/971 Shafi Ahmedzay P 04/10/2018 construction of a new apartment on the first floor over 31/01/2019 107/2019 existing fast food takeaway, side entrance and all associated site works 1 Shelbourne Terrace, Limerick. -

Environmental Impact Assessment Report

Environmental Impact Assessment Report Mixed Use Development - Opera Site, Limerick Limerick City and County Council March 2019 Environmental Impact Assessment Report Limerick City and County Council Environmental Impact Assessment Report Limerick City and County Council Prepared for: Limerick City and County Council Prepared by: AECOM Limited 9th Floor, The Clarence West Building 2 Clarence Street West Belfast BT2 7GP United Kingdom T: +44 28 9060 7200 aecom.com © 2018 AECOM Limited. All Rights Reserved. This document has been prepared by AECOM Limited (“AECOM”) for sole use of our client (the “Client”) in accordance with generally accepted consultancy principles, the budget for fees and the terms of reference agreed between AECOM and the Client. Any information provided by third parties and referred to herein has not been checked or verified by AECOM, unless otherwise expressly stated in the document. No third party may rely upon this document without the prior and express written agreement of AECOM. Environmental Impact Assessment Report Limerick City and County Council Table of Contents 1 Introduction ........................................................................................... 1-1 2 Background / Site Location and Context .............................................. 2-1 3 Description of the proposed development ............................................ 3-1 4 Examination of Alternatives .................................................................. 4-1 5 Non-Statutory Consultations ............................................................... -

Helping Our Customers Live Longer, Stronger and Healthier Lives

Helping our customers live longer, stronger and healthier lives Vhi Annual Report and Accounts 2018 CONTENTS Board of Directors 4 Executive Management Team 6 Chairman’s Review 10 Operations Review 14 Directors’ Report for the Financial Year Ended 31 December 2018 20 Directors’ Responsibilities Statement 26 Independent Auditor’s Report to the Members of the Voluntary Health Insurance Board 27 Consolidated Income and Expenditure Account for the Financial Year ended 31 December 2018 29 Consolidated Balance Sheet as at 31 December 2018 30 Board Balance Sheet as at 31 December 2018 32 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows as at 31 December 2018 33 Board Statement of Cash Flows as at 31 December 2018 33 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity as at 31 December 2018 34 Consolidated Statement of Comprehensive Income for the Financial Year Ended 31 December 2018 34 Board Statement of Changes in Equity as at 31 December 2018 35 Board Statement of Comprehensive Income for the Financial Year Ended 31 December 2018 35 Notes to the Financial Statements 36 Energy Management and Sustainability 62 Company Details 63 Vhi Annual Report and Accounts 2018 | 1 ZAYRA I went to hospital for an allergic reaction. My mum used Snap & Send to claim on the Vhi app. 2 | Vhi Annual Report and Accounts 2018 Digital Health and Wellness 3,585,200 In 2018 MyVhi users accessed their online accounts over 3.5 million times and the Vhi App was utilised over 710K times. Vhi have partnered with a number of innovative providers to bring a range of telehealth benefits and services to customers including Online Doctor, Nurseline 24/7, Health Screening, One to One Midwife and Mental Health Support. -

Limerick Clare Kerry Replacement Waste Management Plan

Evaluation of the Replacement Waste Management Plan for the Limerick/Clare/Kerry Region 2006-2011 Evaluation of the Replacement Waste Management Plan for the Limerick/Clare/Kerry Region Page 1 Replacement Waste Management Plan for the December 2012 Limerick/Clare/Kerry Region 2006-2011 LIST OF TABLES:................................................................................1 LIST OF FIGURES:..............................................................................2 ABBREVIATIONS:...............................................................................3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY........................................................................4 1.0 INTRODUCTION............................................................................6 2.0 LEGISLATIVE UPDATE....................................................................7 3.1Targets..........................................................................................................8 3.2 Inter-Regional Movements of Waste.............................................................8 3.3 Cost Recovery..............................................................................................8 4.0 WASTE PREVENTION...................................................................10 4.1 Waste Prevention Community/Household Level:........................................10 Fig 4.1 Household Waste Management & Generated per captia L/C/K REGION 2008-2010.....................................................................................................11 Fig 4.2 Household -

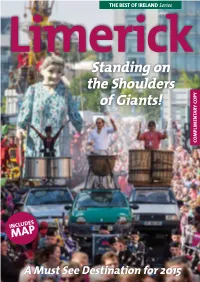

Limerick Guide

THE BEST OF IRELAND Series LimerickStanding on the Shoulders of Giants! COMPLIMENTARY COPY COMPLIMENTARY INCLUDES MAP A Must See Destination for 2015 Limerick Guide Lotta stories in this town. This town. This old, bold, cold town. This big town. This pig town. “Every house a story…This gets up under your skin town…Fill you with wonder town…This quare, rare, my ho-o-ome is there town. Full of life town. Extract from Pigtown by local playwright, Mike Finn. Editor: Rachael Finucane Contributing writers: Rachael Finucane, Bríana Walsh and Cian Meade. Photography: Lorcan O’Connell, Dave Gaynor, Limerick City of Culture, Limerick Marketing Company, Munster Images, Tarmo Tulit, Rachael Finucane and others (see individual photos for details). 2 | The Best Of Ireland Series Limerick Guide Contents THE BEST OF IRELAND Series Contents 4. Introducing Limerick 29. Festivals & Events 93. Further Afield 6. Farewell National 33. Get Active in Limerick 96. Accommodation City of Culture 2014 46. Family Fun 98. Useful Information/ 8. History & Heritage Services 57. Shopping Heaven 17. Arts & Culture 100. Maps 67. Food & Drink A Tourism and Marketing Initiative from Southern Marketing Design Media € For enquiries about inclusion in updated editions of this guide, please contact 061 310286 / [email protected] RRP: 3.00 No part of this publication may be reproduced without the written permission of the publishers. © Southern Marketing Design Media 2015. Every effort has been made in the production of this magazine to ensure accuracy at the time of publication. The editors cannot be held responsible for any errors or omissions, or for any alterations made after publication. -

Magnificent Monaleen House on Market

HOME & INTERIORS JANUARY 28, 2017 This superb detached four-bedroom residence sits in one of the most desirable addresses in all of Limerick within easy reach of every amenity you could need Magnificent Monaleen house on market The Castletroy/Monaleen It has been tastefully dec- If you are interested in located on the left hand side. area is one of the most desir- Facts at a glance orated with high quality fin- viewing this property ring A for sale sign with Rooney able addresses in Limerick ishes throughout and Rooney Auctioneers for an Auctioneers sign has been and RooneyAuctioneers are recently upgraded bath- ap p oi n tm e nt . erected outside. delighted to bring to the Location: 36 Hazel Hall, Monaleen, Castletroy ro o m s . Directions to the property: market a magnificent home Description: 4 bedroom detached home It is an ideal home situated Travel from Limerick out the FEATURES: - Gas fired at 36 Hazel Hall, Monaleen. Price: €3 3 5 ,0 0 0 Seller: Rooney Auctioneers in a quiet cul de sac avenue Dublin Road (R445.Atthe central heating. Thereisbound to be huge Tel: 061 413511 and within ahighly desirable Kilmurry Roundabout take - Double glazed windows interest in this fine four bed- and sought after residential the third exit off right passing th roug h out roomed detached house. l o c at io n . SuperValu on theleft hand - Bathrooms have been up- It is stunning both inside Viewing of the house is s id e. graded within thelast few and outside with a cobblelock highly recommended. -

Discover a Vibrant City and County! Limerick Guide

THE BEST OF IRELAND Series Limerick COMPLIMENTARY COPY COMPLIMENTARY INCLUDES MAP Discover a Vibrant City and County! Limerick Guide Lotta stories in this town. This town. This old, bold, cold town. This big town. This pig town. “Every house a story…This gets up under your skin town…Fill you with wonder town…This quare, rare, my ho-o-ome is there town. Full of life town. Extract from Pigtown by local playwright, Mike Finn. Editor: Rachael Finucane Editorial Assistant: Adam Leahy Contributing writers: Rachael Finucane, Bríana Walsh and Adam Leahy. Photography: Lorcan O’Connell, Dave Gaynor, Limerick Marketing, Rachael Finucane, Fáilte Ireland, Tourism Ireland and others (see individual photos for details). Copyright retained by photographers/organisations. 2 | The Best Of Ireland Series Limerick Guide Contents THE BEST OF IRELAND Series Contents 4. Introducing Limerick 35. Get Active in Limerick 93. Further Afield 6. History & Heritage 48. Family Fun 96. Accommodation 15. Arts, Culture & 57. Shopping Heaven 98. Useful Information/ Education Services 69. Food & Drink 31. Festivals & Events 100. Maps A Tourism and Marketing Initiative from Southern Marketing Design Media € For enquiries about inclusion in updated editions of this guide, please contact 061 310286 / [email protected] RRP: 3.00 No part of this publication may be reproduced without the written permission of the publishers. © Southern Marketing Design Media 2016. Every effort has been made in the production of this magazine to ensure accuracy at the time of publication. The editors cannot be held responsible for any errors or omissions, or for any alterations made after publication. Cover image: St. -

Insurance Mediation) Regulations, 2005

Register of Insurance & Reinsurance Intermediaries European Communities (Insurance Mediation) Regulations, 2005 Insurance Mediation Register: A list of Insurance & Reinsurance Intermediaries registered under the European Communities (Insurance Mediation) Regulations, 2005 (as amended). Registration of insurance/reinsurance intermediaries by the Central Bank of Ireland, does not of itself make the Central Bank of Ireland liable for any financial loss incurred by a person because the intermediary, any of its officers, employees or agents has contravened or failed to comply with a provision of these regulations, or any condition of the intermediary’s registration, or because the intermediary has become subject to an insolvency process. Ref No. Intermediary Registered As Registered on Tied to* Persons Responsible** Passporting Into C29473 123 Money Limited Insurance Intermediary 23 May 2006 Holmes Alan France t/a 123.ie Germany 3rd Floor Spain Mountain View United Kingdom Central Park Leopardstown Dublin 18 C31481 A Better Choice Ltd Insurance Intermediary 31 May 2007 Sean McCarthy t/a ERA Downey McCarthy 8 South Mall Cork C6345 A Callanan & Co Insurance Intermediary 31 July 2007 5 Lower Main Street Dundrum Dublin 14 C70109 A Plus Financial Services Limited Insurance Intermediary 18 January 2011 Paul Quigley United Kingdom 4 Rathvale Park Ayrfield Dublin 13 C1400 A R Brassington & Company Insurance Intermediary 31 May 2006 Cathal O'brien United Kingdom Limited t/a Brassington Insurance, Quickcover IFG House Booterstown Hall Booterstown Co Dublin C42521 A. Cleary & Sons Ltd Insurance Intermediary 30 March 2006 Deirdre Cleary Kiltimagh Enda Cleary Co. Mayo Helen Cleary Paul Cleary Brian Joyce Run Date: 09 February 2015 Page 1 of 389 Ref No. -

Ed 04/11/19 Entered 04/11/19 23:43:08 Main Document Pg 1 of 98

18-13648-smb Doc 710 Filed 04/11/19 Entered 04/11/19 23:43:08 Main Document Pg 1 of 98 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK --------------------------------------------------------x In re : : Chapter 11 WAYPOINT LEASING HOLDINGS : LTD., et al., : Case No. 18-13648 (SMB) : Debtors.1 : (Jointly Administered) --------------------------------------------------------x AFFIDAVIT OF SERVICE I, Stanley Y. Martinez, depose and say that I am employed by Kurtzman Carson Consultants LLC (KCC), the claims and noticing agent for the Debtors in the above-captioned case. On April 8, 2019, at my direction and under my supervision, employees of KCC caused to be served the following documents via Electronic Mail upon the service lists attached hereto as Exhibit B and Exhibit C; and via First Class Mail upon the service list attached hereto as Exhibit D: Chapter 11 Plan of Liquidation of Waypoint Leasing Holdings Ltd. and its Affiliated Debtors [Docket No. 696] Disclosure Statement for Chapter 11 Plan of Liquidation of Waypoint Leasing Holdings Ltd. and its Affiliated Debtors [Docket No. 697] Motion of Debtors for Entry of an Order (I) Approving (A) Proposed Disclosure Statement, (B) Solicitation and Voting Procedures, and (C) Notice and Objection Procedures for Confirmation of Debtors' Plan, and (II) Granting Related Relief [Docket No. 699] (Continued on Next page) 1 A list of the Debtors in these Chapter 11 Cases, along with the last four digits of each Debtor’s federal tax identification number, is annexed hereto as Exhibit A. 18-13648-smb Doc 710 Filed 04/11/19 Entered 04/11/19 23:43:08 Main Document Pg 2 of 98 18-13648-smb Doc 710 Filed 04/11/19 Entered 04/11/19 23:43:08 Main Document Pg 3 of 98 Exhibit A Debtors 18-13648-smb Doc 710 Filed 04/11/19 Entered 04/11/19 23:43:08 Main Document Pg 4 of 98 Debtor Last 4 Debtor Last 4 Digits of Digits of Tax ID Tax ID Number Number Waypoint Leasing Holdings Ltd. -

Report Template Normal Planning Appeal

Inspector’s Report ABP 304028-19 Development Redevelopment of the Opera site for mixed use development including offices, retail and non retail services, cafes/restaurants, licenced premises, apart-hotel, civic/cultural uses, residential, refurbishment of protected structures and open space. Location Site bounded by Michael Street, Rutland Street, Patrick Street and Bank Place, Limerick. Applicant Limerick City and County Council Type of Application Local Authority Project Section 175 Planning and Development Act 2000, as amended. Observers 1. Bon Secure Hospital Limerick 2. Brown Thomas 3. Cait Ni Cheallachain 4. Connolly Menswear & Others ABP 304028-19 Inspector’s Report Page 1 of 131 5. Elizabeth Hatz 6. Euro Car Parks 7. Gerard Carty 8. Hugh Murray 9. Hunt Café and Catering Company 10. IDA Ireland 11. International Rugby Experience 12. Jan Frohburg 13. Limerick Chamber 14. Limerick Chapter of Irish Georgian Society 15. Labour Party Limerick City Constituency 16. Limerick Civic Trust 17. Mary Immaculate College 18. Matthew Stephens Jewellers 19. Office of Public Works 20. Peter Carroll 21. Shannon Foynes Port Company 22. Shannon Group 23. Tara Robinson 24. Tesco Ireland Ltd. 25. The Hunt Museum 26. Tiernan Properties Holdings 27. UL Hospital Group 28. University of Limerick Prescribed Bodies 1. An Taisce, Limerick Association 2. Department of Culture, Heritage ABP 304028-19 Inspector’s Report Page 2 of 131 and the Gaeltacht 3. Geological Survey of Ireland 4. HSE West 5. Inland Fisheries Ireland 6. Irish Water 7. National Transport Authority 8. Transport Infrastructure Ireland Oral Hearing 26th and 27th November, 2019 Dates of Site Inspection 29th October and 25th November, 2019 Inspector Pauline Fitzpatrick Appendices 1. -

Register of Current Licences Under Section 16 of the Local Government Water Pollution Acts 1977 - 2007 to Discharge Trade Effluent to a Public Sewer

Register Of Current Licences under Section 16 of the Local Government Water Pollution Acts 1977 - 2007 to Discharge Trade Effluent to a Public Sewer Updated: 23 December 2015 Licence No Rev IW File Ref File Ref Licencee Name Address1 Address2 Address3 Issued 08.01 308/270L BB's Coffee & Muffins 9B Denmark Street Limerick 21/01/2008 (Denmark St) 08.03 308/374L La Picolla Pizzeria Italia 55 O'Connell Street Limerick 21/01/2008 08.07 308/352L Greene's Café 63 William Street Limerick 26/02/2013 08.08 308/359L The Hunt Café The Hunt Museum 19 Rutland St. Limerick 20/03/2008 08.11 308/394L Mortell's Delicatessan 49 Roches Street Limerick 23/06/2008 08.19 308/425L The Railway Hotel 34 Parnell St Limerick 25/06/2013 08.20 308/304L Clarion Hotel Steamboat Quay Limerick 25/06/2008 08.33 308/381L Luigis Parnell Grill 44/45 Parnell Street Limerick 30/06/2008 08.34 732018 308/469L Woodfield House Hotel Ennis Road Greystones Limerick 18/06/2008 08.39 308/442L The Cellar Restaurant ( 118 O'Connell St Limerick 18/06/2008 O'Grady's) 08.42 308/353L Luca's Fish & Chip Grove Island Shopping Corbally Limerick 15/07/2013 Centre 08.43 308/375L Lets Do Coffee Café Limerick Enterprise Roxborough Limerick 15/07/2008 (LEDP) Development Park 08.44 308/447L Subway O'Connell St 123 O'Connell St Limerick 08/07/2008 08.45 308/448L Subway William St 42 Upper William St Limerick 08/07/2013 08.48 308/423L Quigley's Bakery Parkway Parkway Shopping Centre Singland Limerick 15/07/2008 08.51 308/350L Aimswood Ltd t/a Doc's The Granary Michael Street Limerick 15/07/2008 Bar -

Mortgage Credit Intermediary

Register of authorised Mortgage Credit Intermediaries/Mortgage Intermediaries pursuant to Section 31(10) of the European Union (Consumer Mortgage Credit Agreements) Regulations 2016 and Section 151A (1) of the Consumer Credit Act 1995 The firms listed below are authorised by the Central Bank of Ireland to act as Mortgage Credit Intermediaries/Mortgage Intermediaries in the State for the undertakings listed in the Appointments section below. Ref No. Intermediary Commencement Expiry Date Tied To Appointments Activities Persons Passporting Into Date Responsible C87222 A.G.S. Financial Services Limited 17 September 2012 16 September 2022 Best Rate Mortgages Advisory Services Alasdair Sutton Block B Limited, Brokers Mortgage Credit The Crescent Building Ireland Network Intermediation Northwood Services Limited Santry Dublin 9 C50814 AAA C.K. Life Pensions and 28 November 2013 27 November 2023 Brokers Ireland Advisory Services Carol McCabe Mortgages Limited Network Services Mortgage Credit Declan Keegan t/a CK Financial Solutions Limited, Dilosk DAC Intermediation Mary Flynn No. 1 St Johns Sheila Cassidy Blackhall Mullingar Co Westmeath Ireland C29670 Absolute Mortgages Limited 27 June 2017 26 June 2027 AvantCard DAC, Advisory Services Ciaran Pope Absolute Mortgages Brokers Ireland Mortgage Credit 78 Prospect Hill Network Services Intermediation Galway Limited, Dilosk DAC, H91WR6P Finance Ireland Credit Solutions DAC, Haven Mortgages Limited, KBC Bank Ireland plc, permanent tsb plc., Seniors Money Mortgages (Ireland) Designated Activity Company,