NEGATIVE FIVE in the SHADE a Written Creative Work Submitted To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

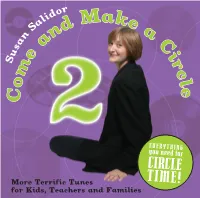

C Ome and Make a Circle

r do li ake a M a S d n n C a a i s r u e c S l m e o C EVERYTHING you need for CIRCLE TIME! More Terrific Tunes for Kids, Teachers and Families Come and Make a Circle 2 More Terrific Tunes for Kids, Teachers and Families In this follow up recording to the first Come and Make a Circle you will find more songs and fingerplays guaranteed to make your circle times fun and successful. Once again I invite you to use all or any part of this CD to create your own circle time repertoire. The songs are divided into the following categories: Let’s Sing, Favorite Fingerplays, Rhythm & Rhyme, Songs That Teach, Old Favorites, and Time to End. Each category contains a handful of songs that will engage and entertain children from 1–6 years. These songs have been carefully selected so that they can be easily learned by early childhood educators with or without prior musical experience. You will find the lyrics to the songs and fingerplays in this booklet, but for teaching tips and movement suggestions, please visit my website at www.susansalidor.com and look for the special Come and Make a Circle 2 button. For more songs and fingerplays for the classroom and home, try Come and Make a Circle, winner of the following awards: Parents’ Choice, NAPPA, iParenting Media, and the Oppenheim Toy Portfolio Gold Award. All of my recordings for children are available at my website (www.SusanSalidor.com) and through dozens of online distributors. -

JUSTICE LEAGUE (NEW 52) CHARACTER CARDS Original Text

JUSTICE LEAGUE (NEW 52) CHARACTER CARDS Original Text ©2012 WizKids/NECA LLC. TM & © 2012 DC Comics (s12) PRINTING INSTRUCTIONS 1. From Adobe® Reader® or Adobe® Acrobat® open the print dialog box (File>Print or Ctrl/Cmd+P). 2. Click on Properties and set your Page Orientation to Landscape (11 x 8.5). 3. Under Print Range>Pages input the pages you would like to print. (See Table of Contents) 4. Under Page Handling>Page Scaling select Multiple pages per sheet. 5. Under Page Handling>Pages per sheet select Custom and enter 2 by 2. 6. If you want a crisp black border around each card as a cutting guide, click the checkbox next to Print page border. 7. Click OK. ©2012 WizKids/NECA LLC. TM & © 2012 DC Comics (s12) TABLE OF CONTENTS Aquaman, 8 Wonder Woman, 6 Batman, 5 Zatanna, 17 Cyborg, 9 Deadman, 16 Deathstroke, 23 Enchantress, 19 Firestorm (Jason Rusch), 13 Firestorm (Ronnie Raymond), 12 The Flash, 20 Fury, 24 Green Arrow, 10 Green Lantern, 7 Hawkman, 14 John Constantine, 22 Madame Xanadu, 21 Mera, 11 Mindwarp, 18 Shade the Changing Man, 15 Superman, 4 ©2012 WizKids/NECA LLC. TM & © 2012 DC Comics (s12) 001 DC COMICS SUPERMAN Justice League, Kryptonian, Metropolis, Reporter FROM THE PLANET KRYPTON (Impervious) EMPOWERED BY EARTH’S YELLOW SUN FASTER THAN A SPEEDING BULLET (Charge) (Invulnerability) TO FIGHT FOR TRUTH, JUSTICE AND THE ABLE TO LEAP TALL BUILDINGS (Hypersonic Speed) AMERICAN WAY (Close Combat Expert) MORE POWERFUL THAN A LOCOMOTIVE (Super Strength) Gale-Force Breath Superman can use Force Blast. When he does, he may target an adjacent character and up to two characters that are adjacent to that character. -

The Symbolic Annihilation of the Black Woman in Rap Videos: a Content Analysis

The Symbolic Annihilation of the Black Woman in Rap Videos: A Content Analysis Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Manriquez, Candace Lynn Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 28/09/2021 03:10:19 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/624121 THE SYMBOLIC ANNIHILATION OF THE BLACK WOMAN IN RAP VIDEOS: A CONTENT ANALYSIS by Candace L. Manriquez ____________________________ Copyright © Candace L. Manriquez 2017 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATION In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2017 Running head: THE SYMBOLIC ANNIHILATION OF THE BLACK WOMAN 2 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR The thesis titled The Symbolic Annihilation of the Black Woman: A Content Analysis prepared by Candace Manriquez has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for a master’s degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that an accurate acknowledgement of the source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his or her judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. -

Benger, Kurt Oral History Interview Steve Hochstadt Bates College

Bates College SCARAB Shanghai Jewish Oral History Collection Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library 6-8-1990 Benger, Kurt oral history interview Steve Hochstadt Bates College Follow this and additional works at: http://scarab.bates.edu/shanghai_oh Recommended Citation Hochstadt, Steve, "Benger, Kurt oral history interview" (1990). Shanghai Jewish Oral History Collection. 1. http://scarab.bates.edu/shanghai_oh/1 This Oral History is brought to you for free and open access by the Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library at SCARAB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Shanghai Jewish Oral History Collection by an authorized administrator of SCARAB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Interview with Kurt Benger by Steve Hochstadt Shanghai Jewish Community Oral History Project Summary Sheet and Transcript Interviewee Benger, Kurt Interviewer Hochstadt, Steve Transcriptionists Das, Kankana Vazirani, Jyotika Hochstadt, Steve Date 6/8/1990 Extent 2 audiocassettes Place Long Beach, California Use Restrictions © Steve Hochstadt. This transcript is provided for individual Research Purposes Only; for all other uses, including publication, reproduction and quotation beyond fair use, permission must be obtained in writing from: Steve Hochstadt, c/o The Edmund S. Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library, Bates College, 70 Campus Avenue, Lewiston, Maine 04240-6018. Biographical Note Kurt Benger was born in Grimmen, Germany, in November 1908. He worked in the clothing business, but was fired from Karstadt in Hamburg in April 1933 because he was Jewish. He later moved to Berlin, where he got married on November 15, 1938, just before they left for Shanghai on November 23. In Shanghai he held many jobs, and had to take care of his wife, Friedel, who was very sick. -

IDW Continued BATWOMAN ELEKTRA DOCTOR WHO INVADER

DARK HORSE IDW Continued MARVEL Continued ! ABE SAPIEN ! MY LITTLE PONY ! MOON GIRL / DEVIL DINOSAUR ! ANGEL & FAITH ! STAR TREK ! MOON KNIGHT ! BPRD ! TMNT ONGOING ! MOSAIC ! BUFFY ! TMNT- Other - Be specific please ! MS MARVEL ! CONAN ! TRANSFORMERS - Be specific please ! NOVA ! HARROW COUNTY ! X-FILES ! OCCUPY AVENGERS ! HELLBOY IMAGE ! OLD MAN LOGAN ! TOMB RAIDER ! BEAUTY ! PATSY WALKER HELLCAT ! USAGI YOJIMBO ! BIRTHRIGHT ! POWER MAN & IRON FIST DC / VERTIGO COMICS ! BLACK SCIENCE ! PROWLER ! ACTION COMICS ! DEADLY CLASS ! PUNISHER ! ALL-STAR BATMAN ! DESCENDER ! ROCKET RACCOON ! AMERICAN VAMPIRE ! EAST OF WEST ! SCARLET WITCH ! AQUAMAN ! FIX ! SILK ! ASTRO CITY ! GOD COUNTRY ! SILVER SURFER ! BATGIRL ! I HATE FAIRYLAND ! SPIDER-GWEN ! BATGIRL & BIRDS OF PREY ! INVINCIBLE ! SPIDER-MAN ! BATMAN ! KILL OR BE KILLED ! SPIDER-MAN / DEADPOOL ! BATMAN 66 ! LOW ! SPIDER-MAN 2099 ! BATMAN BEYOND ! MONSTRESS ! SPIDER-WOMAN ! BATWOMAN ! NAILBITER ! SQUADRON SUPREME ! BLUE BEETLE ! OUTCAST ! STAR WARS ! CATWOMAN ! PAPER GIRLS ! STAR WARS POE DAMERON ! CAVE CARSON Has a Cybernetic Eye ! REVIVAL ! STAR WARS: DARTH MAUL ! CYBORG ! ROM ! STAR WARS: DOCTOR APHRA ! DC COMICS: BOMBSHELLS ! SAGA ! STAR-LORD ! DEATHSTROKE ! SEVEN TO ETERNITY ! THANOS ! DETECTIVE COMICS ! SOUTHERN BASTARDS ! THUNDERBOLTS ! DOCTOR FATE ! SPAWN ! TOTALLY AWESOME HULK ! DOOM PATROL ! THE FEW ! U.S. AVENGERS ! EARTH 2 SOCIETY ! WALKING DEAD ! ULTIMATES 2 ! FALL & RISE OF CAPTAIN ATOM ! WAYWARD ! UNBEATABLE SQUIRREL GIRL ! FLASH ! WICKED & THE DIVINE ! UNCANNY AVENGERS ! -

Traditional Funk: an Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio

University of Dayton eCommons Honors Theses University Honors Program 4-26-2020 Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Caleb G. Vanden Eynden University of Dayton Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/uhp_theses eCommons Citation Vanden Eynden, Caleb G., "Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio" (2020). Honors Theses. 289. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/uhp_theses/289 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the University Honors Program at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Honors Thesis Caleb G. Vanden Eynden Department: Music Advisor: Samuel N. Dorf, Ph.D. April 2020 Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Honors Thesis Caleb G. Vanden Eynden Department: Music Advisor: Samuel N. Dorf, Ph.D. April 2020 Abstract Recognized nationally as the funk capital of the world, Dayton, Ohio takes credit for birthing important funk groups (i.e. Ohio Players, Zapp, Heatwave, and Lakeside) during the 1970s and 80s. Through a combination of ethnographic and archival research, this paper offers a pedagogical approach to Dayton funk, rooted in the styles and works of the city’s funk legacy. Drawing from fieldwork with Dayton funk musicians completed over the summer of 2019 and pedagogical theories of including black music in the school curriculum, this paper presents a pedagogical model for funk instruction that introduces the ingredients of funk (instrumentation, form, groove, and vocals) in order to enable secondary school music programs to create their own funk rooted in local history. -

Stories from the Heart of Australia, the Stories of Its People

O UR GIFT TO Y O U Stories from the PENNING THE P ANDEMIC EDIT ED B Y J OHANNA S K I NNE R & JANE C O NNO L LY Inner Cover picture – Liz Crispie Inner Cover design – Danielle Long Foreword – Johanna Skinner and Jane Connolly Self-Isolation – Margaret Clifford Foreword Late in 2019 news reports of a highly virulent virus were emerging from China. No one could imagine then what would follow. As a general practitioner working at a busy Brisbane surgery, I really did not think that it would affect us that much. How wrong I was. Within months, the World Health Organisation had named the virus COVID 19 and a pandemic was declared. Life as we knew it was changed, perhaps forever. I was fortunate to be part of a practice that had put protocols in place should the worst happen, but even so, I felt overwhelmed by the impact on the patients that I was in contact with daily. They poured their hearts out with stories of resilience, heartache and lives changed irrevocably. I contacted my friend Jane, an experienced editor and writer, about my idea to collect these tales into an anthology. In less than five minutes, she responded enthusiastically and became its senior editor, bringing her years of experience and sharp eye to detail to the anthology. Together, we spent many weekends over pots of tea and Jane’s warm scones reading the overwhelming number of stories and poems that the public entrusted to us. Our greatest regret was that we couldn’t accommodate every piece we received. -

The ONE and ONLY Ivan

KATHERINE APPLEGATE The ONE AND ONLY Ivan illustrations by Patricia Castelao Dedication for Julia Epigraph It is never too late to be what you might have been. —George Eliot Glossary chest beat: repeated slapping of the chest with one or both hands in order to generate a loud sound (sometimes used by gorillas as a threat display to intimidate an opponent) domain: territory the Grunt: snorting, piglike noise made by gorilla parents to express annoyance me-ball: dried excrement thrown at observers 9,855 days (example): While gorillas in the wild typically gauge the passing of time based on seasons or food availability, Ivan has adopted a tally of days. (9,855 days is equal to twenty-seven years.) Not-Tag: stuffed toy gorilla silverback (also, less frequently, grayboss): an adult male over twelve years old with an area of silver hair on his back. The silverback is a figure of authority, responsible for protecting his family. slimy chimp (slang; offensive): a human (refers to sweat on hairless skin) vining: casual play (a reference to vine swinging) Contents Cover Title Page Dedication Epigraph Glossary hello names patience how I look the exit 8 big top mall and video arcade the littlest big top on earth gone artists shapes in clouds imagination the loneliest gorilla in the world tv the nature show stella stella’s trunk a plan bob wild picasso three visitors my visitors return sorry julia drawing bob bob and julia mack not sleepy the beetle change guessing jambo lucky arrival stella helps old news tricks introductions stella and ruby home -

Karaoke Book

10 YEARS 3 DOORS DOWN 3OH!3 Beautiful Be Like That Follow Me Down (Duet w. Neon Hitch) Wasteland Behind Those Eyes My First Kiss (Solo w. Ke$ha) 10,000 MANIACS Better Life StarStrukk (Solo & Duet w. Katy Perry) Because The Night Citizen Soldier 3RD STRIKE Candy Everybody Wants Dangerous Game No Light These Are Days Duck & Run Redemption Trouble Me Every Time You Go 3RD TYME OUT 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL Going Down In Flames Raining In LA Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 3T 10CC Here Without You Anything Donna It's Not My Time Tease Me Dreadlock Holiday Kryptonite Why (w. Michael Jackson) I'm Mandy Fly Me Landing In London (w. Bob Seger) 4 NON BLONDES I'm Not In Love Let Me Be Myself What's Up Rubber Bullets Let Me Go What's Up (Acoustative) Things We Do For Love Life Of My Own 4 PM Wall Street Shuffle Live For Today Sukiyaki 110 DEGREES IN THE SHADE Loser 4 RUNNER Is It Really Me Road I'm On Cain's Blood 112 Smack Ripples Come See Me So I Need You That Was Him Cupid Ticket To Heaven 42ND STREET Dance With Me Train 42nd Street 4HIM It's Over Now When I'm Gone Basics Of Life Only You (w. Puff Daddy, Ma$e, Notorious When You're Young B.I.G.) 3 OF HEARTS For Future Generations Peaches & Cream Arizona Rain Measure Of A Man U Already Know Love Is Enough Sacred Hideaway 12 GAUGE 30 SECONDS TO MARS Where There Is Faith Dunkie Butt Closer To The Edge Who You Are 12 STONES Kill 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER Crash Rescue Me Amnesia Far Away 311 Don't Stop Way I Feel All Mixed Up Easier 1910 FRUITGUM CO. -

“I Am the Villain of This Story!”: the Development of the Sympathetic Supervillain

“I Am The Villain of This Story!”: The Development of The Sympathetic Supervillain by Leah Rae Smith, B.A. A Thesis In English Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved Dr. Wyatt Phillips Chair of the Committee Dr. Fareed Ben-Youssef Mark Sheridan Dean of the Graduate School May, 2021 Copyright 2021, Leah Rae Smith Texas Tech University, Leah Rae Smith, May 2021 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to share my gratitude to Dr. Wyatt Phillips and Dr. Fareed Ben- Youssef for their tutelage and insight on this project. Without their dedication and patience, this paper would not have come to fruition. ii Texas Tech University, Leah Rae Smith, May 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS………………………………………………………….ii ABSTRACT………………………………………………………………………...iv I: INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………….1 II. “IT’S PERSONAL” (THE GOLDEN AGE)………………………………….19 III. “FUELED BY HATE” (THE SILVER AGE)………………………………31 IV. "I KNOW WHAT'S BEST" (THE BRONZE AND DARK AGES) . 42 V. "FORGIVENESS IS DIVINE" (THE MODERN AGE) …………………………………………………………………………..62 CONCLUSION ……………………………………………………………………76 BIBLIOGRAPHY …………………………………………………………………82 iii Texas Tech University, Leah Rae Smith, May 2021 ABSTRACT The superhero genre of comics began in the late 1930s, with the superhero growing to become a pop cultural icon and a multibillion-dollar industry encompassing comics, films, television, and merchandise among other media formats. Superman, Spider-Man, Wonder Woman, and their colleagues have become household names with a fanbase spanning multiple generations. However, while the genre is called “superhero”, these are not the only costume clad characters from this genre that have become a phenomenon. -

By JOHN WELLS a M E R I C a N C H R O N I C L E S

AMERICAN CHRONICLES THE 1965-1969 by JOHN WELLS Table of Contents Introductory Note about the Chronological Structure of American Comic Book Chronicles ................. 4 Note on Comic Book Sales and Circulation Data.......................................... 5 Introduction & Acknowledgements ............ 6 Chapter One: 1965 Perception................................................................8 Chapter Two: 1966 Caped.Crusaders,.Masked.Invaders.............. 69 Chapter Three: 1967 After.The.Gold.Rush.........................................146 Chapter Four: 1968 A.Hazy.Shade.of.Winter.................................190 Chapter Five: 1969 Bad.Moon.Rising..............................................232 Works Cited ...................................................... 276 Index .................................................................. 285 Perception Comics, the March 18, 1965, edition of Newsweek declared, were “no laughing matter.” However trite the headline may have been even then, it wasn’t really wrong. In the span of five years, the balance of power in the comic book field had changed dramatically. Industry leader Dell had fallen out of favor thanks to a 1962 split with client Western Publications that resulted in the latter producing comics for themselves—much of it licensed properties—as the widely-respected Gold Key Comics. The stuffily-named National Periodical Publications—later better known as DC Comics—had seized the number one spot for itself al- though its flagship Superman title could only claim the honor of -

Æ‚‰É”·ȯLj¾é “ Éÿ³æ¨‚Å°ˆè¼¯ ĸ²È¡Œ (ĸ“Ⱦ

æ‚‰é” Â·è¯ çˆ¾é “ 音樂專輯 串行 (专辑 & æ—¶é— ´è¡¨) Spectrum https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/spectrum-7575264/songs The Electric Boogaloo Song https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-electric-boogaloo-song-7731707/songs Soundscapes https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/soundscapes-19896095/songs Breakthrough! https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/breakthrough%21-4959667/songs Beyond Mobius https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/beyond-mobius-19873379/songs The Pentagon https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-pentagon-17061976/songs Composer https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/composer-19879540/songs Roots https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/roots-19895558/songs Cedar! https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/cedar%21-5056554/songs The Bouncer https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-bouncer-19873760/songs Animation https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/animation-19872363/songs Duo https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/duo-30603418/songs The Maestro https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-maestro-19894142/songs Voices Deep Within https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/voices-deep-within-19898170/songs Midnight Waltz https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/midnight-waltz-19894330/songs One Flight Down https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/one-flight-down-20813825/songs Manhattan Afternoon https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/manhattan-afternoon-19894199/songs Soul Cycle https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/soul-cycle-7564199/songs