How to Implement an Effective Intervention to Prevent Alcohol Related Harm?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Do You Need to Know to Reduce Your Risk?

What do you need to know to reduce your risk? Understand what high risk drinking is Understand Blood Alcohol Content (BAC) Levels and some key points about BAC Understand what a standard drink size is vs. a typical party drink size Know the signs and symptoms of alcohol poisoning Know the actions to take if someone appears to be suffering from alcohol poisoning High Risk Drinking Participating in drinking games Celebratory drinking (21st birthday, “the big game”, end of semester, graduation, spring break…) Drinking to get drunk Pre-partying/pre-loading Doing shots Chugging Using a funnel, hose, trough or punch bowl Mixing alcohol with any drugs (legal or illegal) Not knowing what you are drinking or how much you are drinking Combining alcohol with energy drinks These are examples, certainly not all the ways you can drink in a high risk fashion. Any drinking that is in high amounts or short periods of time, creating a situation where the body can’t handle the alcohol, is high risk drinking. How the Body Processes Alcohol When a person drinks alcohol, it can enter the bloodstream immediately. The molecular structure of alcohol is small, so the alcohol can be absorbed or transferred into the blood through the walls of the stomach and the small intestine. The stomach actually has a relatively slow absorption rate; it is the small intestine that absorbs most of the alcohol. Once in the bloodstream, alcohol moves through the body and comes into contact with virtually every organ. However, some of the highest concentrations, and certainly the highest impact, is caused by the alcohol when it reaches the brain. -

Easy Open Pull Tab

Easy Open Pull Tab Submitted to the Italian Packaging Technology Competition March 15, 2006 Brian Calcagno Teresa Haynes Hatfield Josh Taylor California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo PROBLEM There are many people in the world who bite their fingernails. Health risks and public annoyance aside, this causes a disability in opening food packages with metal pull-tabs, such as soft drink cans. Since about 100 billion soft drink cans are produced in the U.S. every year (about one per person per day), it’s obvious that these cans are common in every refrigerator (Kyung- Sun). They should be easy to open, and to many they are. However there is still room for improvement to the design, as nailbiters still find some cans difficult to open. Some soft drink can tabs have been rounded at the end, leaving a tiny space for leverage, but this space is only large enough for a strong fingernail. If the person trying to open the package has no such fingernail, he will have a very difficult time getting to his favorite soft drink. A recent innovation in canned soup packaging has used pull-tabs to make can openers obsolete. The larger, heavier design of these poses an even more significant challenge to nailbiters than soda cans. The geometry of the pull tab on these larger cans causes the tabs to resist upward force even more strongly than familiar soda cans. The shape of the score that the tab is supposed to break also affects the amount of force necessary to open the can. -

Alcohol Units a Brief Guide

Alcohol Units A brief guide 1 2 Alcohol Units – A brief guide Units of alcohol explained As typical glass sizes have grown and For example, most whisky has an ABV of 40%. popular drinks have increased in A 1 litre (1,000ml) bottle of this whisky therefore strength over the years, the old rule contains 400ml of pure alcohol. This is 40 units (as 10ml of pure alcohol = one unit). So, in of thumb that a glass of wine was 100ml of the whisky, there would be 4 units. about 1 unit has become out of date. And hence, a 25ml single measure of whisky Nowadays, a large glass of wine might would contain 1 unit. well contain 3 units or more – about the The maths is straightforward. To calculate units, same amount as a treble vodka. take the quantity in millilitres, multiply it by the ABV (expressed as a percentage) and divide So how do you know how much is in by 1,000. your drink? In the example of a glass of whisky (above) the A UK unit is 10 millilitres (8 grams) of pure calculation would be: alcohol. It’s actually the amount of alcohol that 25ml x 40% = 1 unit. an average healthy adult body can break down 1,000 in about an hour. So, if you drink 10ml of pure alcohol, 60 minutes later there should be virtually Or, for a 250ml glass of wine with ABV 12%, none left in your bloodstream. You could still be the number of units is: suffering some of the effects the alcohol has had 250ml x 12% = 3 units. -

Environmental Stress Cracking of Aluminium Alloy Beverage End Scores

MPMA / BSDA / BBPA RECOMMENDED CODE OF PRACTICE ENVIRONMENTAL STRESS CRACKING OF ALUMINIUM ALLOY BEVERAGE END SCORES Table of contents 1. Introduction 2. Technical explanation 3. End manufacturing factors and quality assurance 4. Process / prevention / filling line conditions and equipment specification 5. Test method for assessing the dryness of can Ends 6. Secondary packaging 7. Environment / post manufacture / distribution and storage 8. Training and education 9. Reference documents 10. Figures DATE OF ISSUE: 14 MAY 2001 1. Introduction This Code of Practice has been prepared and agreed jointly by MPMA (Metal Packaging Manufacturers’ Association), BSDA (British Soft Drinks Association) and British Beer and Pub Association. It is based on current best practice and will be subject to annual review. Detailed technical specifications should be agreed between individual suppliers and customers. 2. Technical Explanation Aluminium alloy beer and soft drink can Ends have been long established as successful components, but can undergo an external corrosion failure process at the score due to reaction with moisture, leading to the tabs popping outwards suddenly. The failure is commonly termed stress corrosion cracking and typically occurs in shrink-wraps or cartons held in warehouses. Failure risks through stress corrosion are especially high in hot and humid climates e.g. temperatures above 30°C and humidity above 60%rh (relative humidity). Depending on the variations in these conditions and other related factors contained in this technical brief, failures from within 2 weeks to several months after filling may occur. Figure 1 describes a cross section of an easy-open End and illustrates the area of failure. -

Go Green Living Guide

GO GREEN ST. TAMMANY A GREEN LIVING GUIDE FOR ST. TAMMANY PRODUCED BY ST. TAMMANY PARISH GOVERNMENT DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL SERVICES www.stpgov.org/Green-Living DOS AND DON'TS OF HOUSEHOLD HAZARDOUS WASTE To make sure you are recycling and disposing of Household Hazardous Waste correctly, take a minute to read over these topics. You may discover that you have been doing something wrong all along. DO DO DO Look carefully for a natu- Read the label and follow Keep all chemicals out of ral, non-hazardous substi- use, storage and disposal the reach of children and tute before buying. directions carefully. pets. DON’T DO DON’T Mix chemical products or Completely finish products Re-purpose pesticide or wastes. Dangerous, toxic in containers before dis- other chemical containers. reactions can occur. posal. DO DON’T DO Select water-based prod- Store corrosives, flamma- Choose the pump spray or ucts over solvent-based bles and poisons together. other alternatives rather products when available. than aerosol sprays. FLAMMABLE SOLIDS ARE DANGEROUS! These are solid wastes that pose a fire threat. Flammable solids are materials that have the potential to ignite by friction or heat sources, or by contact with other chemicals. The danger associated with flammable solids is that they have the potential to combust. Flammability is one of the more common dangers of hazardous wastes and must be watched carefully. Exam- ples of flammable solids are charcoal, matches, candles and silicon based caulking products. DID YOU KNOW... USED MOTOR OIL IS A HAZARDOUS WASTE? Used motor oil is a hazardous waste and cannot go into your curbside garbage or trash for pickup. -

Feasting in Homeric Epic 303

HESPERIA 73 (2004) FEASTING IN Pages 301-337 HOMERIC EPIC ABSTRACT Feasting plays a centralrole in the Homeric epics.The elements of Homeric feasting-values, practices, vocabulary,and equipment-offer interesting comparisonsto the archaeologicalrecord. These comparisonsallow us to de- tect the possible contribution of different chronologicalperiods to what ap- pearsto be a cumulative,composite picture of around700 B.c.Homeric drink- ing practicesare of particularinterest in relation to the history of drinkingin the Aegean. By analyzing social and ideological attitudes to drinking in the epics in light of the archaeologicalrecord, we gain insight into both the pre- history of the epics and the prehistoryof drinkingitself. THE HOMERIC FEAST There is an impressive amount of what may generally be understood as feasting in the Homeric epics.' Feasting appears as arguably the single most frequent activity in the Odysseyand, apart from fighting, also in the Iliad. It is clearly not only an activity of Homeric heroes, but also one that helps demonstrate that they are indeed heroes. Thus, it seems, they are shown doing it at every opportunity,to the extent that much sense of real- ism is sometimes lost-just as a small child will invariablypicture a king wearing a crown, no matter how unsuitable the circumstances. In Iliad 9, for instance, Odysseus participates in two full-scale feasts in quick suc- cession in the course of a single night: first in Agamemnon's shelter (II. 1. thanks to John Bennet, My 9.89-92), and almost immediately afterward in the shelter of Achilles Peter Haarer,and Andrew Sherrattfor Later in the same on their return from their coming to my rescueon variouspoints (9.199-222). -

Modernist Vintages: the Significance of Wine in Wilde, Richardson, Joyce

Modernist Vintages: The Significance of Wine in Wilde, Richardson, Joyce and Waugh by Laura Waugh A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Approved March 2013 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Mark Lussier, Chair Daniel Bivona Patrick Bixby ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY May 2013 ABSTRACT “Modernist Vintages” considers the significance of wine in a selection of modernist texts that includes Oscar Wilde’s Salomé (1891), Dorothy Richardson’s Honeycomb (1917), James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922), and Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited: The Sacred and Profane Memories of Captain Charles Ryder (1945). The representations of wine in these fictions respond to the creative and destructive depictions of Wine that have imbued the narratives of myth, religion, and philosophy for thousands of years; simultaneously, these WorKs recreate and reflect on numerous Wine-related events and movements that shaped European discourse in the nineteenth and tWentieth centuries. The modernists use Wine’s conventional associations to diverse and innovative ends: as the playWright August Strindberg Writes, “NeW forms have not been found for the neW content, so that the neW Wine has burst the old bottles.” Wine in these works alternately, and often concurrently, evoKes themes that Were important to the modernists, including notions of indulgence and Waste, pleasure and addiction, experimentation and ritual, tradition and nostalgia, regional distinction and global expansion, wanton intoxication and artistic clarity. -

How Can Recycling Help Our Communities and Our Environment?

HOW CAN RECYCLING HELP OUR COMMUNITIES AND OUR ENVIRONMENT? How many times can cardboard be recycled? How many tons of recycled glass goes into making new bottles and jars every year? Can I recycle my plastic bottle with the cap on? Learn the answers to these questions and share these fun facts to teach others why recycling matters. What you can recycle is different in every community so be sure to check your local program’s website for the most up-to-date information. Did You Know: 1. The average person creates almost five pounds of trash per day, and in 2018, American consumers created 146.2 million tons of trash that ended up in landfills. Thankfully, Americans also recycled and composted almost 94 million tons of waste – a rate that has grown more than 300% in the past 38 years. 2. Cardboard (also known as corrugated) boxes can be recycled at least seven times and can be used to make new packaging boxes and even furniture. The best part is recycling cardboard is easy. Almost all Americans having access to curbside recycling for their corrugated boxes. Just make sure they are empty, dry, clean, and flattened. 3. How long does it take for a used aluminum drink can to be recycled into a new one and put back on the grocery shelf? Just 60 days. It’s a good thing, too, because Americans love to recycle aluminum cans, which are recycled more often than any other type of drink container and can be recycled over and over again. 4. -

The Aluminium Drink Can Is the Most Recycled Drinks Container on the Planet

The aluminium drink can is the most recycled drinks container on the planet. Aluminium can be recycled over and over again, saving energy and natural resources – and reducing litter and waste. Every minute of every day, an average of 113,200 aluminium cans are recycled. One of the largest aluminium can recycling plants in Europe is in Warrington, Cheshire. Novelis is the world’s largest recycler of aluminium drink cans. In 2016, the company recycled 60 billion cans, enough to circle the world more than 162 times (if laid end to end). Around 8.5 billion aluminium cans are sold every year in the UK, and in 2015 an estimated 5.9 billion were recycled. The amount of liquid held in the 5.9 billion drinks cans that are recycled into new aluminium products each year could fill 760 Olympic sized swimming pools, and would fill Wembley Stadium halfway to its roof. Recycling aluminium cans saves energy, conserves natural resources, and cuts down the amount of waste that needs to be buried in landfill sites. Recycling one aluminium can saves enough energy to run a television for three hours. Used aluminium drink cans can be recycled and back on supermarket shelves as new drink cans in as little as 60 days. Anything made of aluminium can be recycled repeatedly – not only cans, but aluminium foil, food trays, window frames, automotive components. All can be melted down and used to make the same (or other) products again. Recycling aluminium takes 95% less energy than producing it from its raw materials. The recycling process also generates only 5% of the greenhouse gas emissions. -

Standard Drink Equivalents Alcohol, According to a Report from the U.S

14 ACPINTERNIST PATIENT COMMUNICATION Alcohol continued from page 1 Cancer Society, the American Society of About 30% of the U.S. population misuses Clinical Oncology, and the American Heart Standard drink equivalents alcohol, according to a report from the U.S. Association all recommend no more than Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) one drink per day for women and one to published in the Sept. 25, 2012, Annals of two for men. Beer or cooler 12 oz = 1 Internal Medicine . The USPSTF reported that The definition of a drink in all of the 12 oz, 16 oz = 1.3 21.3% of patients in primary care are risky recommendations is 12 oz of regular beer ~5% alcohol 22 oz = 2 drinkers who consume on average more than (which contains about 5% alcohol), 5 oz of 40 oz = 3.3 four drinks per day if they are men or more red or white table wine (about 12% alco - than two drinks per day if they are women. hol), or 1.5 oz of 80-proof spirits (about 40% “The topic of alcohol habits should be alcohol). Those standard-size drinks each Malt liquor 12 oz = 1.5 asked by every health practitioner of every contain about 12.5 to 15 mL of pure ethyl 8-9 oz, 16 oz = 2 patient who comes for care,” said Arthur alcohol (see chart at right). ~7% alcohol 22 oz = 2.5 Klatsky, MD, FACP, adjunct investigator at Understanding the difference between 40 oz = 4.5 the Kaiser Permanente Northern California serving size and alcohol content is impor - Division of Research and senior consultant tant. -

Share Memories , Not Regrets

SHARE MEMORIES, NOT REGRETS GUIDELINES FOR RESPONSIBLE CONSUMPTION Contributer & Designer: SHARE MEMORIES NOT REGRETS Jade Ross, Texas Alcohol Beverage Commission - Education/ Prevention , Kayla Bridgewaters, Texas Alcohol Beverage Commission - Education/ Prevention GUIDELINES FOR RESPONSIBLE CONSUMPTION A Publication by: The Texas Alcoholic Beverage Commission Responsible Consumption Let’s Start With Some Stats What is responsible consumption? Deaths Assaults An estimated 1,825 The consequences of An estimated Responsibilty goes hand-in-hand with independence. As you get older and more college students excessive and underage 696,000 college independent, responsibility becomes more important because the choices you make die each year from drinking affect everyone in students are affect other people. In terms of consuming alcohol responsibly, personal choices on unintentional, the college community. assaulted by how much you drink can affect your own future as well as the futures of others. alcohol-related another student It doesn’t matter if the injuries, including who has been motor vehicle students are younger or drinking each year. older than 21. DRINKING ALCOHOL crashes. Injuries Sexual Abuse It doesn’t matter if the An estimated COMES WITH RESPONSIBILITIES! An estimated students choose to drink 599,000 college 97,000 college students are Not all college students drink. However, according to the NIAAA, about four of every or not. students are victims unintentionally five college students drink alcohol. This includes about 60 percent of students ages 18 of alcohol-related Everyone is impacted injured under the to 20. Approximately 40 percent of college students have reported engaging in binge sexual assault or by decisions to drink influence of alcohol 4 drinking at least once during the previous two weeks. -

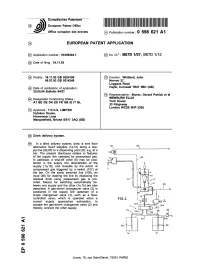

Drink Delivery System

Europaisches Patentamt 19 European Patent Office Office europeen des brevets © Publication number: 0 598 621 A1 12 EUROPEAN PATENT APPLICATION © Application number : 93309204.1 © int. ci.5: B67D 1/07, B67D 1/12 @ Date of filing : 18.11.93 © Priority : 18.11.92 GB 9224189 @ Inventor : Whitford, John 09.07.93 GB 9314248 Norvoc 27, Loggans Road © Date of publication of application : HaVle> Cornwall TR27 5BH (GB) 25.05.94 Bulletin 94/21 @ Representative : Stoner, Gerard Patrick et al ELUS @ Designated Contracting States : vE\!'uURN AT BE DE DK ES FR GB IE IT NL If.,. 6 23 Kingsway ^ London WC2B 6HP (GB) © Applicant : T.K.C.S. LIMITED Hytoken House, Howsmoor Lane Mangotsfield, Bristol BS17 3AQ (GB) © Drink delivery system. © In a drink delivery system, drink is sent from alternative liquid supplies (1a, 1b) along a sup- ply line (92,93) to a dispensing point (8), e.g. at a bar. The present disclosure relates to features of the supply line operated by pressurised gas. In particular, a shut-off valve (6) may be posi- tioned in the supply line downstream of the supply (1a, 1b), and closable by the action of compressed gas triggered by a switch (107) at the bar. On the same switched line (106), an input (46) for clearing the line by displacing the residual drink using pressurised gas is pro- vided. Means for switching automatically be- tween one supply and the other (1a, 1b) are also described. A gas-driven changeover valve (2) is positioned in the supply line upstream of a single changeover valve (3), such as a float- controlled valve, which is operated when a current supply approaches exhaustion, to actuate the gas-driven changeover valve (2) and thereby connect the other supply.