Modernist Vintages: the Significance of Wine in Wilde, Richardson, Joyce

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paul's Letters Script

Paul’s Letters Episode 05 Second Thessalonians Script There I was sitting in my frigid house with a bit of a hangover, wrapped in a blanket. It was January, I’d been out all night. I was musing about the month being named after Janus, the two- faced Roman god. It was said that Janus could see the past and the future at the same time. That’d be awesome, because if I could see the future, I would soon be rich enough to buy all the liquor and women I could want! The Apostle Paul had been staying at my house, I wasn’t the best host, being out all night. He had almost convinced me that my Roman gods were not real. I was on the verge of becoming a Christian, but let’s just say I wasn’t quite ready to give up my wild lifestyle. All of a sudden, reverie interrupted. A group of totally out of control dudes burst through my door. Rough dudes. Rougher than me. What could I do but sit there quietly as they ransacked my house looking for Paul and Silas. Finally, I got their attention. “Paul and Silas aren't here,” I shouted. They were out, somewhere. So, they grabbed me instead. They dragged me toward the city officials. And I wasn’t the only one either, they were also dragging a few people I recognized who had become believers in Jesus. At the town center, the officials were in a turmoil. A few Jews and the rough dudes - accused me of hosting someone who opposed the Roman government, someone who followed a king other than Caesar. -

Race and Membership in American History: the Eugenics Movement

Race and Membership in American History: The Eugenics Movement Facing History and Ourselves National Foundation, Inc. Brookline, Massachusetts Eugenicstextfinal.qxp 11/6/2006 10:05 AM Page 2 For permission to reproduce the following photographs, posters, and charts in this book, grateful acknowledgement is made to the following: Cover: “Mixed Types of Uncivilized Peoples” from Truman State University. (Image #1028 from Cold Spring Harbor Eugenics Archive, http://www.eugenics archive.org/eugenics/). Fitter Family Contest winners, Kansas State Fair, from American Philosophical Society (image #94 at http://www.amphilsoc.org/ library/guides/eugenics.htm). Ellis Island image from the Library of Congress. Petrus Camper’s illustration of “facial angles” from The Works of the Late Professor Camper by Thomas Cogan, M.D., London: Dilly, 1794. Inside: p. 45: The Works of the Late Professor Camper by Thomas Cogan, M.D., London: Dilly, 1794. 51: “Observations on the Size of the Brain in Various Races and Families of Man” by Samuel Morton. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences, vol. 4, 1849. 74: The American Philosophical Society. 77: Heredity in Relation to Eugenics, Charles Davenport. New York: Henry Holt &Co., 1911. 99: Special Collections and Preservation Division, Chicago Public Library. 116: The Missouri Historical Society. 119: The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, 1882; John Singer Sargent, American (1856-1925). Oil on canvas; 87 3/8 x 87 5/8 in. (221.9 x 222.6 cm.). Gift of Mary Louisa Boit, Julia Overing Boit, Jane Hubbard Boit, and Florence D. Boit in memory of their father, Edward Darley Boit, 19.124. -

What Do You Need to Know to Reduce Your Risk?

What do you need to know to reduce your risk? Understand what high risk drinking is Understand Blood Alcohol Content (BAC) Levels and some key points about BAC Understand what a standard drink size is vs. a typical party drink size Know the signs and symptoms of alcohol poisoning Know the actions to take if someone appears to be suffering from alcohol poisoning High Risk Drinking Participating in drinking games Celebratory drinking (21st birthday, “the big game”, end of semester, graduation, spring break…) Drinking to get drunk Pre-partying/pre-loading Doing shots Chugging Using a funnel, hose, trough or punch bowl Mixing alcohol with any drugs (legal or illegal) Not knowing what you are drinking or how much you are drinking Combining alcohol with energy drinks These are examples, certainly not all the ways you can drink in a high risk fashion. Any drinking that is in high amounts or short periods of time, creating a situation where the body can’t handle the alcohol, is high risk drinking. How the Body Processes Alcohol When a person drinks alcohol, it can enter the bloodstream immediately. The molecular structure of alcohol is small, so the alcohol can be absorbed or transferred into the blood through the walls of the stomach and the small intestine. The stomach actually has a relatively slow absorption rate; it is the small intestine that absorbs most of the alcohol. Once in the bloodstream, alcohol moves through the body and comes into contact with virtually every organ. However, some of the highest concentrations, and certainly the highest impact, is caused by the alcohol when it reaches the brain. -

EVELYN WAUGH NEWSLETTER and STUDIES Volume 34

EVELYN WAUGH NEWSLETTER AND STUDIES Volume 34 EVELYN WAUGH NEWSLETTER AND STUDIES Volume 34, Number 1 Spring 2003 Evelyn Waugh Centenary Conference Schedule Monday, 22 September 2003 9:30 a.m. Arrival at Castle Howard, Yorkshire 10:00-11:15 a.m. Private tour of Castle Howard 11:15-12:30 p.m. Free time 12:30-1:30 p.m. Luncheon 2:00-3:15 p.m. Brideshead Revisited tour of the Grounds 3:15-4:15 p.m. Lecture on Castle Howard 4:15-5:15 p.m. Afternoon Tea Tuesday, 23 September 2003 Travel to Hertford College, Oxford Wednesday, 24 September 2003 9:00 a.m. Arrival and Registration 9:30 a.m. Panel: Waugh and Modernism Eulàlia Carceller Guillamet, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Chair The Persistence of Waste Lands in Waugh’s Fiction K. J. Gilchrist, Iowa State University "I Must Have a Lot of That": Modernity, Hybridity, and Knowledge in Black Mischief Lewis MacLeod, Memorial University of Newfoundland Eliot and Waugh: A Handful of Dust Sally C. Hoople, Maine Maritime Academy "The Age of Hooper": Brideshead Revisited, Modernism, and the Welfare State Peter Kalliney, University of South Florida-St. Petersburg Against Emotion: Evelyn Waugh's Modernistic Stance Alain Blayac, University of Montpellier 12:00 noon Luncheon 2:00 p.m. Walking tour of Waugh’s Oxford (weather permitting) John Howard Wilson, Lock Haven University of Pennsylvania Patrick Denman Flanery, St Cross College, Oxford Sebastian Perry, Merton College, Oxford 4:00 p.m. Afternoon Tea 5:00 p.m. Visit to Campion Hall (half of group) 6:30 p.m. -

Spoon River Anthology (Abridged by Bill Fellner)

Spoon River Anthology (abridged by Bill Fellner) [The Hill] 4 Where are Elmer, Herman, Bert, Tom and Charley, The weak of will, the strong of arm, the clown, the boozer, the fighter? All, all are sleeping on the hill. One passed in a fever, One was burned in a mine, One was killed in a brawl, One died in a jail, One fell from a bridge toiling for children and wife-- All, all are sleeping, sleeping, sleeping on the hill. Where are Ella, Kate, Mag, Lizzie and Edith, The tender heart, the simple soul, the loud, the proud, the happy one?-- All, all are sleeping on the hill. One died in shameful child-birth, One of a thwarted love, One at the hands of a brute in a brothel, One of a broken pride, in the search for heart's desire; One after life in far-away London and Paris Was brought to her little space by Ella and Kate and Mag-- All, all are sleeping, sleeping, sleeping on the hill. Where are Uncle Isaac and Aunt Emily, And old Towny Kincaid and Sevigne Houghton, And Major Walker who had talked With venerable men of the revolution?-- All, all are sleeping on the hill. They brought them dead sons from the war, And daughters whom life had crushed, And their children fatherless, crying-- All, all are sleeping, sleeping, sleeping on the hill. Where is Old Fiddler Jones Who played with life all his ninety years, Braving the sleet with bared breast, Drinking, rioting, thinking neither of wife nor kin, Nor gold, nor love, nor heaven? Lo! he babbles of the fish-frys of long ago, Of the horse-races of long ago at Clary's Grove, Of what Abe Lincoln said One time at Springfield. -

Two-Gun Bill: the Story of William S. Hart, 1987

TWO-GUN BILL The Story of Williatn S. Hart by KATHERINE H. CHILD illiam S. Hart not only got "While playing in Cle. veland [in 1913], I attended that chance to make West a picture show. I saw a Western picture. W ern motion pictures, he It was awful! I talked with the manager of made the best of it. In spite of their early popularity, Western films were, as Hart the theater and he told me it was one of the best had seen, exercises in mediocrity. When Hart came to California in 1914, he Westerns he had ever had. Npne of the impossibilities brought with him a fresh approach to or libels on the West meant anything to him-it was Western film making. He added authen tic costumes and locales to a heretofore drawing the crowds .... I was so sure that I had made popular, highly idealized image of the West to create a truly original style for a big discovery that I was frightened that some one his films. Much as the work of Frederic would read my mind and find it out. Remington and Charles Russell has come to be emblematic of the West in the Here were reproductions of the Old West being art world, so does the work of William seriously presented to the public-in almost a bur S. Hart symbolize the West on film. Though he was not the first Western lesque manner-and they were successful. It made me actor/ film maker nor the last, he was surely one of the most important, tremble to think of it. -

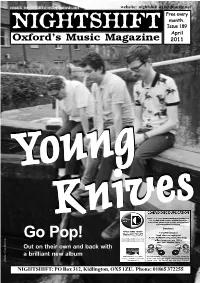

Issue 189.Pmd

email: [email protected] NIGHTSHIFTwebsite: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every Oxford’s Music Magazine month. Issue 189 April 2011 YYYYYYoungoungoungoung KnivesKnivesKnivesKnives Go Pop! Out on their own and back with a brilliant new album photo: Cat Stevens NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net WILCO JOHNSON AND listings for the weekend, plus ticket DEACON BLUE are the latest details, are online at names added to this year’s www.oxfordjazzfestival.co.uk Cornbury Festival bill. The pair join already-announced headliners WITNEY MUSIC FESTIVAL returns James Blunt, The Faces and for its fifth annual run this month. Status Quo on a big-name bill that The festival runs from 24th April also includes Ray Davies, Cyndi through to 2nd May, featuring a Lauper, Bellowhead, Olly Murs, selection of mostly local acts across a GRUFF RHYS AND BELLOWHEAD have been announced as headliners The Like and Sophie Ellis-Bextor. dozen venues in the town. Amongst a at this year’s TRUCK FESTIVAL. Other new names on the bill are host of acts confirmed are Johnson For the first time Truck will run over three full days, over the weekend of prog-folksters Stackridge, Ben Smith and the Cadillac Blues Jam, 22nd-24th July at Hill Farm in Steventon. The festival will also enjoy an Montague & Pete Lawrie, Toy Phousa, Alice Messenger, Black Hats, increased capacity and the entire site has been redesigned to accommodate Hearts, Saint Jude and Jack Deer Chicago, Prohibition Smokers new stages. -

Where Did They Go

BRITISH ‘BABY BOOMER’ NOSTALGIA Compiled by David Challinor Saluting AA Men Cream on Milk The Children’s Newspaper Shaving in Barbers Time Guns Foot X-Ray Machines in Shoe Shops Pea Shooters Pushers-up Same Day Post Passing Bells Subscription Libraries Boxing Kangaroos Dunces Caps Home-made Fireworks Aluminium Nameplate Machines at Stations German Bands Breton Onion Sellers Romany Caravans Ceiling Clocks Paint Boxes Electric Shock Therapy Bona Fide Travellers Bird – Nesting Apache Dancing Audiphones Aunt Sallies John Bull Puncture Repair Outfits & Printing sets Office Boys White Sugar Mice Camp Coffee Crystal Radio Sets Gas Mantles Guineas Boys Shouting the News Life Preservers Liquorice Imps/ Sherbet Pipes and Dabs Lobby Lud Cigarette Cards Driving Cattle through Towns Tripe Shops Continuous Performance School Ink, Inkwells and Ink Monitors Paper Chases Skipping Seasonal Children’s Games (conkers, marbles) Muffin Men Gob-stoppers Rag and Bone Men (goldfishes for junk) Beetle Drives Card Indexes in Libraries Change Receptacles on Overhead Wire Pulleys Reins on Toddlers Silver Cigarette Cases ‘Fly-proof’ Metal Grilles on Meat-safes Sticky Fly Paper DDT Memory Men (Leslie Welch) Kewpie Dolls Cigarette Holders Bells to Call the Chambermaid in hotel rooms Children’s Gardens Music Halls Pierrots/Black and White Minstrels School Milk Empire Day Pork Butchers Polite Children Blackberrying Laxative Chocolate Tuck Shops Ticking Clocks Flying Boats Rubber Bathing Caps Train Spotting Buying Pickles by the Basin Motor Cycle Sidecars Milk Churns Errand -

Easy Open Pull Tab

Easy Open Pull Tab Submitted to the Italian Packaging Technology Competition March 15, 2006 Brian Calcagno Teresa Haynes Hatfield Josh Taylor California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo PROBLEM There are many people in the world who bite their fingernails. Health risks and public annoyance aside, this causes a disability in opening food packages with metal pull-tabs, such as soft drink cans. Since about 100 billion soft drink cans are produced in the U.S. every year (about one per person per day), it’s obvious that these cans are common in every refrigerator (Kyung- Sun). They should be easy to open, and to many they are. However there is still room for improvement to the design, as nailbiters still find some cans difficult to open. Some soft drink can tabs have been rounded at the end, leaving a tiny space for leverage, but this space is only large enough for a strong fingernail. If the person trying to open the package has no such fingernail, he will have a very difficult time getting to his favorite soft drink. A recent innovation in canned soup packaging has used pull-tabs to make can openers obsolete. The larger, heavier design of these poses an even more significant challenge to nailbiters than soda cans. The geometry of the pull tab on these larger cans causes the tabs to resist upward force even more strongly than familiar soda cans. The shape of the score that the tab is supposed to break also affects the amount of force necessary to open the can. -

Alcohol Units a Brief Guide

Alcohol Units A brief guide 1 2 Alcohol Units – A brief guide Units of alcohol explained As typical glass sizes have grown and For example, most whisky has an ABV of 40%. popular drinks have increased in A 1 litre (1,000ml) bottle of this whisky therefore strength over the years, the old rule contains 400ml of pure alcohol. This is 40 units (as 10ml of pure alcohol = one unit). So, in of thumb that a glass of wine was 100ml of the whisky, there would be 4 units. about 1 unit has become out of date. And hence, a 25ml single measure of whisky Nowadays, a large glass of wine might would contain 1 unit. well contain 3 units or more – about the The maths is straightforward. To calculate units, same amount as a treble vodka. take the quantity in millilitres, multiply it by the ABV (expressed as a percentage) and divide So how do you know how much is in by 1,000. your drink? In the example of a glass of whisky (above) the A UK unit is 10 millilitres (8 grams) of pure calculation would be: alcohol. It’s actually the amount of alcohol that 25ml x 40% = 1 unit. an average healthy adult body can break down 1,000 in about an hour. So, if you drink 10ml of pure alcohol, 60 minutes later there should be virtually Or, for a 250ml glass of wine with ABV 12%, none left in your bloodstream. You could still be the number of units is: suffering some of the effects the alcohol has had 250ml x 12% = 3 units. -

University of Birmingham Oscar Wilde, Photography, and Cultures Of

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Portal University of Birmingham Oscar Wilde, photography, and cultures of spiritualism Dobson, Eleanor License: None: All rights reserved Document Version Peer reviewed version Citation for published version (Harvard): Dobson, E 2020, 'Oscar Wilde, photography, and cultures of spiritualism: ''The most magical of mirrors''', English Literature in Transition 1880-1920, vol. 63, no. 2, pp. 139-161. Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: Checked for eligibility 12/02/2019 Published in English Literature in Transition 1880-1920 http://www.eltpress.org/index.html General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. -

Blavatsky Will Instruct Me in the Seven Sacred Trances

Thomas Stearns Eliot Blavatsky will instruct me in the seven sacred trances Blavatsky will instruct me in the Seven Sacred Trances v. 19.10, www.philaletheians.co.uk, 1 February 2019 Page 1 of 3 BLAVATSKY TRIBUTES SERIES T.S. ELIOT ON THE SEVEN SACRED TRANCES 1 A Cooking Egg En l’an trentiesme de mon aage 2 Que toutes mes hontes j’ay beues . Pipit sate upright in her chair Some distance from where I was sitting; Views of the Oxford Colleges Lay on the table, with the knitting. Daguerreotypes and silhouettes, Her grandfather and great great aunts, Supported on the mantelpiece An Invitation to the Dance. I shall not want Honour in Heaven For I shall meet Sir Philip Sidney And have talk with Coriolanus And other heroes of that kidney. I shall not want Capital in Heaven For I shall meet Sir Alfred Mond. We two shall lie together, lapt In a five per cent. Exchequer Bond. I shall not want Society in Heaven, Lucretia Borgia shall be my Bride; Her anecdotes will be more amusing Than Pipit’s experience could provide. 1 First appeared in T.S. Eliot’s second collection of Poems, 1919. For a short analysis of the poem click here. 2 i.e., “By the 30th year of my life, I have drunk up all my shame,” epigraph from François Villon, the best known French poet of the late Middle Ages. Blavatsky will instruct me in the Seven Sacred Trances v. 19.10, www.philaletheians.co.uk, 1 February 2019 Page 2 of 3 BLAVATSKY TRIBUTES SERIES T.S.