SAN DIEGO No More Mr. Niche Guy: Multidimensional

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Objection Résolution Di ECR “Lead Gunshot in Or Around Wetlands”- Risultati Votazione Per Appello Nominale

Objection Résolution di ECR “Lead gunshot in or around Wetlands”- Risultati votazione per appello nominale Favorevoli 292 + ECR Aguilar, Sergio Berlato (FRATELLI D’ITALIA- Intergruppo Caccia), Buxadé Villalba, de la Pisa Carrión, Dzhambazki, Eppink, Carlo Fidanza (FRATELLI D’ITALIA- Intergruppo Caccia ) , Pietro Fiocchi (FRATELLI D’ITALIA- Intergruppo Caccia ) , Raffaele Fitto (FRATELLI D’ITALIA - Intergruppo Caccia ) , Geuking, Kempa, Lundgren, Nicola Procaccini (FRATELLI D’ITALIA- Intergruppo Caccia ) , Rooken, Roos, Ruissen, Slabakov, Raffaele Stancanelli (FRATELLI D’ITALIA- Intergruppo Caccia ) Stegrud, Terheş, Tertsch, Tomaševski, Tomašić, Tošenovský, Vondra, Vrecionová, Weimers, Zahradil GUE/NGL: Konečná, MacManus ID: Matteo Adinolfi (LEGA- Intergruppo Caccia) , Anderson, Androuët, Annemans, Simona Baldassarre (LEGA), Bardella , Alessandra Basso (LEGA), Bay, Beck, Berg, Bilde, Mara Bizzotto (LEGA- Intergruppo Caccia ) , Blaško, Anna Cinzia Bonfrisco (LEGA), Paolo Borchia (LEGA), Buchheit, Marco Campomenosi, (LEGA- Intergruppo Caccia ), Massimo Casanova (LEGA- Intergruppo Caccia ) ; Susanna Ceccardi (LEGA- Intergruppo Caccia ) , Angelo Ciocca (LEGA), Collard, Rosanna Conte (LEGA- Intergruppo Caccia) , Gianantonio Da Re, (LEGA- Intergruppo Caccia ) David, De Man, Francesca Donato (LEGA- Intergruppo Caccia ), Marco Dreosto (LEGA- Intergruppo Caccia ), Fest, Gianna Gancia (LEGA), Garraud, Grant, Griset, Haider, Hakkarainen, Huhtasaari, Jalkh, Jamet, Juvin, Krah, Kuhs, Lacapelle, Oscar Lancini (LEGA- Intergruppo Caccia ), Laporte, Lebreton, -

The Hidden Cost of September 11 Liz Fekete

Racism: the hidden cost of September 11 Liz Fekete Racism: the hidden cost of September 11 Liz Fekete A special issue of the European Race Bulletin Globalisation has set up a monolithic economic system; September 11 threatens to engender a monolithic political culture. Together, they spell the end of civil society. – A. Sivanandan, Director, Institute of Race Relations Institute of Race Relations 2-6 Leeke Street, London WC1X 9HS Tel: 020 7837 0041 Fax: 020 7278 0623 Web: www.irr.org.uk Email: [email protected] Liz Fekete is head of European research at the Insitute of Race Relations where she edits the European Race Bulletin. It is published quarterly and available on subscription from the IRR (£10 for individuals, £25 for institutions). •••••• This report was compiled with the help of Saba Bahar, Jenny Bourne, Norberto Laguia Casaus, Barry Croft, Rhona Desmond, Imogen Forster, Haifa Hammami, Lotta Holmberg, Vincent Homolka, Mieke Hoppe, Fida Jeries, Simon Katzenellenbogen, Virginia MacFadyen, Nitole Rahman, Hazel Waters, and Chris Woodall. Special thanks to Tony Bunyan, Frances Webber and Statewatch. © Institute of Race Relations 2002 ISBN 085001 0632 Cover Image by David Drew Designed by Harmit Athwal Printed by Russell Press Ltd European Race Bulletin No. 40 Contents Introduction 1 1. The EU approach to combating terrorism 2 2. Removing refugee protection 6 3. Racism and the security state 10 4. Popular racism: one culture, one civilisation 16 References 22 European Race Bulletin No. 40 Introduction ollowing the events of September 11, it became commonplace to say that the world would Fnever be the same again. -

Italy Failed the Test | International Affairs at LSE

6/19/2017 Italy Failed the Test | International Affairs at LSE Mar 7 2013 Italy Failed the Test LSE IDEAS By Dr. Giulia Bentivoglio, Visiting Fellow at LSE IDEAS. The Italian elections of 2425 February 2013, gave Italians their first chance to vote after the illfated experiment of Mario Monti’s “technocratic government”. These elections were a test in many senses: they were a test for the parties involved to show signs of actual change and detachment from a political system that urgently needed to be cleaned up. They were a test of credibility for the country as a whole, to indicate to its European partners that it was able to achieve the political stability essential to Italy’s economic recovery. Finally, the elections were a test on the Eurozone and the feasibility of continuing austerity. A low electoral turnout (75%) and a widespread protest vote as a reaction to austerity measures resulted in political gridlock and a hung parliament. The Democratic Party (PD) polled the largest share of the vote but failed to gain majority in the Senate: as its leader Pier Luigi Bersani put it, “we did not win, although we came first”. The real winners were Beppe Grillo and Silvio Berlusconi. Grillo’s Five Stars Movement (M5S), formed just three years ago, became the largest party in the Chamber of Deputies, an unprecedented success achieved by a campaign boasting the prophetic name the “tsunami tour” which focused on the new social media and on a populist rhetoric. Berlusconi’s party (People of Freedom – PdL) lost 17% of its voters, but this was the best result possible from someone who seemed to be politically dead in December 2012. -

European Parliament Mid-Term Election: What Impact on Migration Policy?

www.epc.eu 16 March 2017 01/12/2009 European Parliament mid-term election: what impact on migration policy? Marco Funk As the dust settles from the European Parliament’s (EP) mid-term election held on 17 January 2017, migration continues to top the EU’s agenda. The election of Antonio Tajani to replace Martin Schulz as president of the EP brought the institution under the leadership of the European People’s Party (EPP) after a power-sharing agreement with the socialist S&D was cancelled and replaced by a last-minute deal with the liberal ALDE group. A closer look at Tajani’s election and associated reshuffle of key internal positions suggests little change in the EP’s course on migration in the short term. However, upcoming developments may significantly change Parliament dynamics in the longer term. New president, different style Antonio Tajani is considered by many to be a less political, less activist president compared to Martin Schulz. The former is also apparently less willing to insist on a prominent role for the EP than the latter. Furthermore, Tajani shares the same conservative political affiliation as the heads of the European Commission and European Council, which makes ideological confrontations with Jean-Claude Juncker and Donald Tusk even less likely than under Schulz, who had few disagreements with either. While Schulz already maintained good relations with Juncker and closely coordinated responses to the large influx of refugees in 2015/2016, Tajani is even better placed to cooperate effectively due to his previous Commission experience and ideological alignment. Despite Tajani’s association with Italy’s populist conservative leader Silvio Berlusconi, he has adopted a more mainstream conservative political identity, which ultimately won him the EPP’s support. -

Codebook CPDS I 1960-2012

1 Codebook: Comparative Political Data Set I, 1960-2012 Codebook: COMPARATIVE POLITICAL DATA SET I 1960-2012 Klaus Armingeon, Laura Knöpfel, David Weisstanner and Sarah Engler The Comparative Political Data Set 1960-2012 is a collection of political and institutional data which have been assembled in the context of the research projects “Die Handlungs- spielräume des Nationalstaates” and “Critical junctures. An international comparison” di- rected by Klaus Armingeon and funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation. This data set consists of (mostly) annual data for 23 democratic countries for the period of 1960 to 2012. In the cases of Greece, Spain and Portugal, political data were collected only for the democratic periods1. The data set is suited for cross national, longitudinal and pooled time series analyses. The data set contains some additional demographic, socio- and economic variables. Howev- er, these variables are not the major concern of the project and are thus limited in scope. For more in-depth sources of these data, see the online databases of the OECD. For trade union membership, excellent data for European trade unions are available on CD from the Data Handbook by Bernhard Ebbinghaus and Jelle Visser (2000). A few variables have been copied from a data set collected by Evelyne Huber, Charles Ragin, John D. Stephens, David Brady and Jason Beckfield (2004). We are grateful for the permission to include these data. When using data from this data set, please quote both the data set and, where appropriate, the original source. Please quote this data set as: Klaus Armingeon, Laura Knöpfel, David Weisstanner and Sarah Engler. -

LSE European Politics and Policy (EUROPP) Blog: Silvio Is Back: Understanding Berlusconi's Latest Revival Ahead of the Italian

LSE European Politics and Policy (EUROPP) Blog: Silvio is back: Understanding Berlusconi’s latest revival ahead of the Italian general election Page 1 of 3 Silvio is back: Understanding Berlusconi’s latest revival ahead of the Italian general election Despite currently being banned from holding office, Silvio Berlusconi is well placed to have a key role in the Italian general election in March. Fabio Bordignon outlines the factors behind his latest comeback, and how his Forza Italia party could play a central part in the formation of the next Italian government. In the past when we Italian scholars of political science met our colleagues at international conferences, it was always the same question: why Berlusconi? How could a media tycoon, facing multiple-trials and allegations, an unlikely politician later known for his ‘bunga bunga’ parties, have become the leading figure in one of the largest western democracies? The astonishment of the international observer was particularly acute in 2011, when Berlusconi, hit by personal scandals and by the Eurozone debt crisis, resigned as prime minister. Now the world has changed, and it’s full of Berlusconi-style politicians. But at a time when political leaders seem to fade as fast as they rise, Berlusconi is still there. The ‘Eternal Leader’ has survived the collapse of his last government, a ban from the Italian Parliament, and a seemingly irreversible electoral (and personal) decline. And now the 81-year-old leader is ready for a new comeback. He cannot be a candidate, but he still leads (owns) his personal party, Forza Italia. And he could win with his centre-right coalition at the Italian general election in March. -

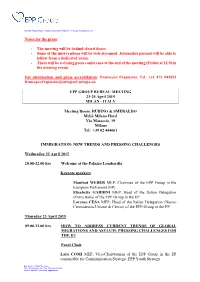

Programme of the Meeting and Press Accreditation Information

Parliamentary Works - Parlamentarische Arbeiten - Travaux Parlementaires Notes for the press: - The meeting will be behind closed doors. - Some of the interventions will be web-streamed. Journalists present will be able to follow from a dedicated room. - There will be a closing press conference at the end of the meeting (Friday at 12.30 in the meeting room). For information and press accreditation: Francesco Frapiccini, Tel: +32 473 941652 [email protected] EPP GROUP BUREAU MEETING 23-24 April 2015 MILAN - ITALY Meeting Room: RUBINO & SMERALDO Meliá Milano Hotel Via Masaccio, 19 Milano Tel: +39 02 444061 IMMIGRATION: NEW TRENDS AND PRESSING CHALLENGES Wednesday 22 April 2015 20.00-22.00 hrs Welcome at the Palazzo Lombardia Keynote speakers Manfred WEBER MEP, Chairman of the EPP Group in the European Parliament (EP) Elisabetta GARDINI MEP, Head of the Italian Delegation (Forza Italia) of the EPP Group in the EP Lorenzo CESA MEP, Head of the Italian Delegation (Nuovo Centrodestra-Unione di Centro) of the EPP Group in the EP Thursday 23 April 2015 09.00-11.00 hrs HOW TO ADDRESS CURRENT TRENDS OF GLOBAL MIGRATIONS AND ASYLUM: PRESSING CHALLENGES FOR THE EU Panel Chair Lara COMI MEP, Vice-Chairwoman of the EPP Group in the EP responsible for Communication Strategy, EPP Youth Strategy Rue Wiertz - B-1047 Bruxelles Tel: +32 (2) 284.21.11 - Fax: +32 (2) 230.97.93 Internet address: http://www.eppgroup.eu Rob WAINWRIGHT, Director of Europol Pier Ferdinando CASINI, President of the International Centre Democratic Party -

Technocratic Governments: Power, Expertise and Crisis Politics in European Democracies

The London School of Economics and Political Science Technocratic Governments: Power, Expertise and Crisis Politics in European Democracies Giulia Pastorella A thesis submitted to the European Institute of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy London, February 2016 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 86852 words, excluding bibliography, appendix and annexes. Statement of joint work Chapter 3 is based on a paper co-authored with Christopher Wratil. I contributed 50% of this work. 2 Acknowledgements This doctoral thesis would have not been possible without the expert guidance of my two supervisors, Professor Sara Hobolt and Doctor Jonathan White. Each in their own way, they have been essential to the making of the thesis and my growth as an academic and as an individual. I would also like to thank the Economic and Social Research Council for their generous financial support of my doctoral studies through their scholarship. -

Activity Report 2011 Centre for European Studies

Our CES Team Credits Activity Report 2011 Centre for European Studies Editors: José Luis Fontalba, Ana María Martín, John Lageson, Erik Zolcer, Rodrigo Castro Publication design: Andreas Neuhaus | PEPATO–GROUP Brussels, December 2011 Centre for European Studies Rue du Commerce 20 B–1000 Brussels The Centre for European Studies (CES) is the political foundation of the European People’s Party (EPP) dedicated to the promotion of Christian Democrat, conservative and like-minded political values. For more information please visit: www.thinkingeurope.eu This publication receives funding from the European Parliament. © Centre for European Studies 2012 Photos used in this publication: © Centre for European Studies 2012 The European Parliament assumes no responsibility for facts or opinions expressed in this publication or their subsequent use. Table of Contents 04 Welcome 06 About us Executive Board (08) Academic Council (10) Research Associates (12) Staff 2011 (14) Visiting Fellows (15) Internships (16) Individual Members (17) CES Member Foundations (18) 20 Research and Publications · Research Research Papers (22) CES Watch and Policy Briefs (24) CES Flashes (25) · Regular Publications European View (26) European Factbook (27) · Collaborative Publications (28) · Other Publications (30) 32 Events · Our Events Economic Ideas Forum (34) International Visitors Programme (38) The Arab Spring Programme (40) 2nd Transatlantic Centre-Right Think Tank Conference (42) NEW ACTIVITY! CES Authors Dinner (44) Freedom in the Days of the Internet (46) Integration -

Civil Society and the State in Democratic East Asia

PROTEST AND SOCIAL MOVEMENTS Chiavacci, (eds) Grano & Obinger Civil Society and the State in Democratic East Asia East Democratic in State the and Society Civil Edited by David Chiavacci, Simona Grano, and Julia Obinger Civil Society and the State in Democratic East Asia Between Entanglement and Contention in Post High Growth Civil Society and the State in Democratic East Asia Protest and Social Movements Recent years have seen an explosion of protest movements around the world, and academic theories are racing to catch up with them. This series aims to further our understanding of the origins, dealings, decisions, and outcomes of social movements by fostering dialogue among many traditions of thought, across European nations and across continents. All theoretical perspectives are welcome. Books in the series typically combine theory with empirical research, dealing with various types of mobilization, from neighborhood groups to revolutions. We especially welcome work that synthesizes or compares different approaches to social movements, such as cultural and structural traditions, micro- and macro-social, economic and ideal, or qualitative and quantitative. Books in the series will be published in English. One goal is to encourage non- native speakers to introduce their work to Anglophone audiences. Another is to maximize accessibility: all books will be available in open access within a year after printed publication. Series Editors Jan Willem Duyvendak is professor of Sociology at the University of Amsterdam. James M. Jasper teaches at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. Civil Society and the State in Democratic East Asia Between Entanglement and Contention in Post High Growth Edited by David Chiavacci, Simona Grano, and Julia Obinger Amsterdam University Press Published with the support of the Swiss National Science Foundation. -

Reuters Euro Zone Summit 2013

REUTERS EURO ZONE SUMMIT 2013 An illuminated euro sign is seen in front of the headquarters of the European Central Bank (ECB) in the late evening in Frankfurt January 8, 2013. REUTERS/ KAI PFAFFENBACH The Euro Zone Crisis is Back ollowing a fractured Italian election result the mour and creating the conditions for the crisis to flare heat is back on the Euro Zone with its auster- up again. Could that be spur to galvanise policymakers Fity mantra offering little to douse growing so- again, following signs they have soft-pedalled on closer cial unease in southern Europe. The European Central economic integration and building a banking union in Bank’s pledge to do whatever it takes to save the euro recent months? The Reuters Euro Zone Summit held took some heat out of the debt crisis but unless Italy over four days in Brussels, Frankfurt, Paris, Madrid and can establish a durable, reform-minded government London pressed a dozen of Europe’s top policymakers it might have put itself outside the ECB’s protection, on their plans, hopes and fears and whether they expect opening a dangerous chink in the currency bloc’s ar- the ECB to have to back up its words with actions. 1 REUTERS EURO ZONE SUMMIT 2013 EU’s Barroso urges leaders to stick to austerity goals BY LUKE BAKER AND MICHAEL STOTT The result leaves the euro zone’s third BRUSSELS, FEBRUARY 26, 2013 largest economy facing an extended period of political uncertainty, with the prospect of uropean Commission President Jose another round of elections if a government Manuel Barroso appealed to EU cannot be formed. -

Islam Councils

THE MUSLIM QUESTION IN EUROPE Peter O’Brien THE MUSLIM QUESTION IN EUROPE Political Controversies and Public Philosophies TEMPLE UNIVERSITY PRESS Philadelphia • Rome • Tokyo TEMPLE UNIVERSITY PRESS Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19122 www.temple.edu/tempress Copyright © 2016 by Temple University—Of Th e Commonwealth System of Higher Education All rights reserved Published 2016 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: O’Brien, Peter, 1960– author. Title: Th e Muslim question in Europe : political controversies and public philosophies / Peter O’Brien. Description: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania : Temple University Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifi ers: LCCN 2015040078| ISBN 9781439912768 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781439912775 (paper : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781439912782 (e-book) Subjects: LCSH: Muslims—Europe—Politics and government. | Islam and politics—Europe. Classifi cation: LCC D1056.2.M87 O27 2016 | DDC 305.6/97094—dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015040078 Th e paper used in this publication meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992 Printed in the United States of America 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 For Andre, Grady, Hannah, Galen, Kaela, Jake, and Gabriel Contents Acknowledgments ix 1 Introduction: Clashes within Civilization 1 2 Kulturkampf 24 3 Citizenship 65 4 Veil 104 5 Secularism 144 6 Terrorism 199 7 Conclusion: Messy Politics 241 Aft erword 245 References 249 Index 297 Acknowledgments have accumulated many debts in the gestation of this study. Arleen Harri- son superintends an able and amiable cadre of student research assistants I without whose reliable and competent support this book would not have been possible.