Signifying Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Measuring Individual Identity: Experimental Evidence

Measuring Individual Identity: Experimental Evidence Alexander Kuo Center for Advanced Study in the Social Sciences Juan March Institute [email protected] Yotam Margalit Department of Political Science Columbia University [email protected] Abstract What determines the identity category people feel they most belong to? What is the political significance of one’s proclaimed identity? Recent research addresses this question using surveys that explicitly ask individuals about their identity. Yet little is known about the nature of the attachments conveyed in responses to identity questions. We conduct a set of studies and experiments that investigate these reported attachments. Our findings suggest that: (1) the purported identity captured in survey responses varies significantly within subjects over time; (2) changes in people’s primary identity can be highly influenced by situational triggers; (3) changes in purported self-identity do not imply a corresponding change in policy preferences. Our results are drawn from three studies that vary in terms of design, country sample, and research instrument. The findings have implications for research on identity choice, as well as on the use of surveys in studying the role of identity in comparative politics. 1 ―We have spoken to many people in this country [X] and they have all described themselves in different ways. Some people describe themselves in terms of their language, religion, race, and others describe themselves in economic terms, such as working class, middle class, or a farmer. Besides being [a citizen of X], which specific group do you feel you belong to first and foremost?‖ [Afrobarometer Surveys, 1999-2002] Introduction What determines the identity category people feel they belong to? What is the political significance of one’s proclaimed identity? The answers to these questions are important for understanding phenomena such as policy preferences, social cleavages, and perhaps even political conflict. -

Download Songlist

ARTISTA/INTERPRETE TITOLO OPERA AUTORE COMPOSITORE AA.VV. Celebre Mazurca Variata (La Migliavacca) Migliavacca AA.VV. Il Ballo Del Somarello G.Piazzolla AA.VV. Medley Cumbia - Successi Italiani - Vol.4 A.Fornaciari AA.VV. Zibaldone Popolare - Vol.2 Aa.Vv. Adamo La Notte S.Adamo Adamo Non Sei Tu S.Adamo Adriano Celentano Fascino Mogol Adriano Celentano Il Ragazzo Della Via Gluck (Live) Celentano Adriano Celentano L'arcobaleno Mogol Adriano Celentano Pregherò (Stand By Me) (Live 2012) King Adriano Celentano Viola De Luca Adriano Pappalardo Ricominciamo L.Albertelli Alan Sorrenti Non So Che Darei A.Sorrenti Alberto Camerini Rock'n'roll Robot A.Camerini Alessandra Amoroso Comunque Andare E.Toffoli Alicia A Natale Puoi (Spot Bauli) F.Vitaloni Alpisella Band Quel Mazzolin Di Fiori F.Marchionni Alunni Del Sole Concerto Rossi Amedeo Minghi 1950 A.Minghi Amedeo Minghi Decenni P.Panella Amedeo Minghi La Vita Mia A.Minghi Amedeo Minghi Notte Bella Magnifica A.Minghi Antonello Venditti Buona Domenica A.Venditti Antonello Venditti Ci Vorrebbe Un Amico A.Venditti Antonello Venditti Cosa Avevi In Mente A.Venditti Antonello Venditti In Questo Mondo Di Ladri A.Venditti Antonello Venditti Notte Prima Degli Esami (Live) A.Venditti Antonello Venditti Ricordati Di Me A.Venditti Antonello Venditti Sotto Il Segno Dei Pesci A.Venditti Antonello Venditti Sotto La Pioggia A.Venditti Antonello Venditti & Francesco De Gregori Canzone Lucio Dalla Arrangiamento Inedito M-Live 'o Surdato 'nnammurato Califano Arrangiamento Inedito M-Live Maracaibo M.L.Colombo Avion Travel Sentimento G.Servillo Banda Bassotti Bella Ciao Popolare Beatles Hey Jude (Radio Edit) J.Lennon Beatles Ob-La-Dì Ob-La-Dà J.Lennon Benji & Fede Dove E Quando E.D.Maimone Biagio Antonacci Ho La Musica Nel Cuore B.Antonacci Biagio Antonacci Iris (Tra Le Tue Poesie) B.Antonacci Biagio Antonacci Lei Lui E Lei B.Antonacci Biagio Antonacci Non Vivo Più Senza Te (Live) B.Antonacci Biagio Antonacci Se È Vero Che Ci Sei B.Antonacci Biagio Antonacci Ft. -

Giulietta E Romeo Save the Date

Giulietta e Romeo SAVE THE DATE CANZONI RACCOLTE PER RINGRAZIARE AMICI E PARENTI NEL NOSTRO GIORNO PIÙ BELLO es yeux qui font baisser les miens Dun rire qui se perd sur sa bouche voilà le portrait sans retouche de l’homme auquel j’appartiens quand il me prend dans ses bras il me parle tout bas je vois la vie en rose. EDITH PIAF, La vie en rose 5 ove me tender loveL me sweet never let me go. You have made my life complete and I love you so. Love me tender love me true all my dreams fulfilled for my darling I love you and I always will. ELVIS PRESLEY, Love me tender 6 on aver paura diN darmi un bacio ma stammi vicino e scaccia i timor. Il nostro amor non potrà mai finire stringiti a me e poi lasciati andar. GIORGIO GABER, Non arrossire 7 he cosa c’è c’èC che mi sono innamorato di te c’è che ora non mi importa niente di tutta l’altra gente di tutta quella gente che non sei tu. GINO PAOLI, Che cosa c’è 8 right are the stars that shine darkB is the sky I know this love of mine will never die and I love her. THE BEATLES, And I love her 9 arà perché mi hai guardato Scome nessuno mi ha guardato mai mi sento viva all’improvviso per te. MINA, Mi sei scoppiato dentro al cuore 10 t’s a little bit funny, this feeling inside Ii’m not one of those who can easily hide. -

International-Short

VOL. VIII AUGUST, 1937 NO.11 INTERNATIONAL Short Wave News. Ten Cents a Copy. Accurate Station List. One Dollar a Year. Hourly Tuning Guide. Published Monthly. THE VOICE OF THE INTERNATIONAL SHORT WAVE CLUB EAST LIVERPOOL, OHIO, U. S. A. Only because the RME-69 was originally engineered as a really fine receiver has it been possible for owners to possess an instrument which TODAY is strictly up-to-the-minute in every detail. Information will be furnished upon request. RADIO MFG. ENGINEERS, INC. 306 FIRST AVENUE PEORIA, ILLINOIS, U. S. A. PERFORMANCE PLUS The 12 -tube NC - 100 Receiver in- cludes every refine- ment for difficult short wave work. The Movable Coil Tuning Unit com- bines the high elec- trical efficiency of plug-in coils with the convenience of the coil switch, and covers from 540 kc. to 30 mc. in five ranges. Idle coils are isolated in cast aluminum shields, leads are short, and calibration is exact. Panel controls are complete, and in- cludes separate switches of B -sup- ply, Filaments, C - W Oscillator, and AVC; as well as dials for Audio Gain, RF Gain, Tone Control, and CW Oscillator Tuning. The pre- cision Micrometer Dial, direct reading to one part in five hundred, provides exceptonal ease of tuning together with great accuracy in logging. These are but a few of the features that com- bine to make the NC -100's perform- ance so outstanding and its low price so remarkable. An illustrated folder will be sent on request. NATIONAL COMPANY, INC., MALDEN, MASS. 4 HELP YOURSELF BY BOOSTING THE CLUB International Short Wave Radio is published monthly by the International Short Wave Club of East Liverpool, Ohio, U. -

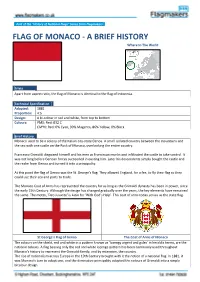

FLAG of MONACO - a BRIEF HISTORY Where in the World

Part of the “History of National Flags” Series from Flagmakers FLAG OF MONACO - A BRIEF HISTORY Where In The World Trivia Apart from aspect ratio, the flag of Monaco is identical to the flag of Indonesia. Technical Specification Adopted: 1881 Proportion: 4:5 Design: A bi-colour in red and white, from top to bottom Colours: PMS: Red: 032 C CMYK: Red: 0% Cyan, 90% Magenta, 86% Yellow, 0% Black Brief History Monaco used to be a colony of the Italian city-state Genoa. A small isolated country between the mountains and the sea with one castle on the Rock of Monaco, overlooking the entire country. Francesco Grimaldi disguised himself and his men as Franciscan monks and infiltrated the castle to take control. It was not long before Genoan forces succeeded in ousting him. Later his descendents simply bought the castle and the realm from Genoa and turned it into a principality. At this point the flag of Genoa was the St. George’s flag. They allowed England, for a fee, to fly their flag so they could use their sea and ports to trade. The Monaco Coat of Arms has represented the country for as long as the Grimaldi dynasty has been in power, since the early 15th Century. Although the design has changed gradually over the years, the key elements have remained the same. The motto, 'Deo Juvante' is Latin for 'With God's Help'. This coat of arms today serves as the state flag. St George’s Flag of Genoa The Coat of Arms of Monaco The colours on the shield, red and white in a pattern known as 'lozengy argent and gules' in heraldic terms, are the national colours. -

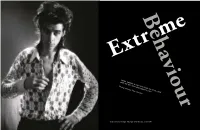

Laura Harker & Paul Sullivan on Nick Cave and the 80S East

Behaviour 11 Extr me LaurA HArKer & PAul SullIvAn On Nick CAve AnD THe 80S East KreuzBerg SCene Photography by Peter gruchot 10 ecords), 24 April 1986 Studio session for the single ‘The Singer’ (Mute r Cutting a discreet diagonal between Kottbusser Tor and Oranienplatz, Dresdener Straße is one of the streets that provides blissful respite from east Kreuzberg’s constant hustle and bustle. Here, the noise of the traffic recedes and the street’s charms surge subtly into focus: fashion boutiques and indie cafés tucked into the ground floors of 19th Century Altbauten, the elegantly run-down Kino Babylon and the dark and seductive cocktail bar Würgeengel, the “exterminating angel”, a name borrowed from a surrealist film by luis Buñuel. It all looked very different in the 80s of course, when the Berlin Wall stood just under a kilometre away and the façades of these houses – now expensively renovated and worth a pretty penny – were still pockmarked by World War Two bulletholes. Mostly devoid of baths, the interiors heated by coal, their inhabitants – mostly Turkish immigrants – shivered and shuffled their way through the Berlin winter. 12 13 It was during this pre-Wende milieu that a tall, skinny and largely unknown Australian musician named Nicholas Edward Cave moved into no. 11. Aside from brief spells in apartments on naumannstraße (Schöneberg), yorckstraße, and nearby Oranienstraße, Cave spent the bulk of his seven on-and-off years in Berlin living in a tiny apartment alongside filmmaker and musician Christoph Dreher, founder of local outfit Die Haut. It was in this house that Cave wrote the lyrics and music for several Birthday Party and Bad Seeds albums, penned his debut novel (And The Ass Saw The Angel) and wielded a sizeable influence over Kreuzberg’s burgeoning post-punk scene. -

University of Groningen True Religion

University of Groningen True Religion: a lost portrait by Albert Szenci Molnár (1606) or Dutch–Flemish–Hungarian intellectual relations in the early-modern period Teszelszky, Kees Published in: Szenci Molnár Albert elveszettnek hitt Igaz Vallás portréja (1606) avagy holland–flamand–magyar szellemi kapcsolatok a kora újkorban - True Religion: a lost portrait by Albert Szenci Molnár (1606) or Dutch–Flemish–Hungarian intellectual relations in the early-modern period IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2014 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Teszelszky, K. (2014). True Religion: a lost portrait by Albert Szenci Molnár (1606) or Dutch–Flemish–Hungarian intellectual relations in the early-modern period. In K. Teszelszky (Ed.), Szenci Molnár Albert elveszettnek hitt Igaz Vallás portréja (1606) avagy holland–flamand–magyar szellemi kapcsolatok a kora újkorban - True Religion: a lost portrait by Albert Szenci Molnár (1606) or Dutch–Flemish–Hungarian intellectual relations in the early-modern period (pp. 81-183). Budapest: ELTE BTK Középkori és Kora Újkori Magyar Történeti Tanszéke and the Transylvania Emlékeiért Tudományos Egyesület. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Laa Cooinaghtyn Illiam Dhone 2020- Roie

Published by Mec Vannin, The Manx Nationalist Party Earroo / Issue 60 Jerrey Geurree / January 2020 Laa Cooinaghtyn Illiam Dhone 2020 - Roie Raa ‘sy Ghaelg liorish Markys y Kermitt Failt erriu ooilley gys Laa Cooinaghtyn er yn R.U., t'eh orrin goaill rish dy vel Manninee faagail er yn oyr nagh vel Illiam Dhone, sy vlein Daa Housane as drogh staid nyn jeer, er y chooid smoo, ee Mannin nish myr t’ad smooinaghtyn Feed. Yn cliaghtey ain rish ymmodee kyndagh rish drogh reiltys 'syn ellan urree. Ta shin lane dy leih ta jeeaghyn bleintyn, shen goaill toshiaght lesh hene. er Mannin myr aght nyn lyst startaghyn roie-raa mychione y vlein chaaie, as as bea y vishaghey as shen ooilley. As eisht oraid Ghaelgagh as oraid elley Ta'n Kiare as Feed bunnys dyn niart ta Sisyphus rolley e chlagh. 'sy Vaarle. erbee. C'raad ta'n niart firrinagh? Vel eh ayns Coonseil ny Shirveishee? Cha Agh cre aght fodmayd cur lhietrymmys Yn vlein shoh, bee daa oraid scanshoil nel eh. Myr smoo as ny smoo, ta'n niart er y laou shoh? Seign da’n reiltys 'sy Vaarle mychione chyndaays ny politickagh 'syn ellan nish ny lhie eddyr aa-hoie keeshyn dy ve kynjagh son h'emshyr as nyn gurrym rish y Oik Coonseil ny Shirveishee as Oik yn ooilley sleih as co-lughtyn ayns chymbyllaght as myr shen, reih shin Turneyr Theayagh as ta'd bunnys dyn Mannin. Seign da’n reiltys goaill rish jannoo yn roie-raa 'sy Ghaelg as y rick politickagh. nagh jean tooilley sleih jannoo veg er Vaarle neesht. -

Flags and Banners

Flags and Banners A Wikipedia Compilation by Michael A. Linton Contents 1 Flag 1 1.1 History ................................................. 2 1.2 National flags ............................................. 4 1.2.1 Civil flags ........................................... 8 1.2.2 War flags ........................................... 8 1.2.3 International flags ....................................... 8 1.3 At sea ................................................. 8 1.4 Shapes and designs .......................................... 9 1.4.1 Vertical flags ......................................... 12 1.5 Religious flags ............................................. 13 1.6 Linguistic flags ............................................. 13 1.7 In sports ................................................ 16 1.8 Diplomatic flags ............................................ 18 1.9 In politics ............................................... 18 1.10 Vehicle flags .............................................. 18 1.11 Swimming flags ............................................ 19 1.12 Railway flags .............................................. 20 1.13 Flagpoles ............................................... 21 1.13.1 Record heights ........................................ 21 1.13.2 Design ............................................. 21 1.14 Hoisting the flag ............................................ 21 1.15 Flags and communication ....................................... 21 1.16 Flapping ................................................ 23 1.17 See also ............................................... -

Selección De Memorias Del Máster De Diplomacia Y Relaciones Internacionales 2017-2018

Selección de memorias del Máster de Diplomacia y Relaciones Internacionales 2017-2018 CUADERNOS DE LA ESCUELA DIPLOMÁTICA Selección de memorias del Máster de Diplomacia y Relaciones Internacionales 2017-2018 Nota Legal A tenor de lo dispuesto en la Ley de Propiedad Intelectual, no está permiti- da la reproducción total o parcial de esta publicación, ni su tratamiento informáti- co, ni la transmisión de ninguna forma o por cualquier medio, ya sea electrónico, por fotocopia, por registro u otros métodos, ni su préstamo, alquiler o cualquier otra forma de cesión de su uso, sin el permiso previo y por escrito del autor, sal- vo aquellas copias que se realicen para uso exclusivo del Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores y de Cooperación”. MINISTERIO DE ASUNTOS EXTERIORES, UNIÓN EUROPEA Y COOPERACIÓN © de los textos sus autores © de la presente edición 2018: Escuela Diplomática Paseo de Juan XXIII, 5 - 28040 Madrid NIPO ESTABLE: (en línea) 108-19-002-1 NIPO ESTABLE: (en papel) 108-19-001-6 ISSN: 0464-3755 Depósito Legal: M-28074-2020 DISEÑA E IMPRIME: IMPRENTA DE LA DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE COMUNICACIÓN, DIPLOMACIA PÚBLICA Y REDES DISEÑO PORTADA: JAVIER HERNÁNDEZ: (www.nolson.com) Reproducción en papel para conservación, consulta en biblioteca y uso exclusivo en sesiones de trabajo. Catálogo General de Publicaciones Oficiales de la Administración del Estado. https://publicacionesoficiales.boe.es "En esta publicación se ha utilizado papel reciclado libre de cloro de acuerdo con los criterios medioambientales de la contratación pública". Índice Nota Legal ........................................................................................................ 6 PRIMERA MEMORIA POR LUIS ÁLVAREZ LÓPEZ EL FESTIVAL DE EUROVISIÓN: un atípico Concierto Europeo ...................................................................... 13 AGRADECIMIENTOS .................................................................................... -

Qui Sont Ces Serpents Qui Sifflent Sur Le Bois Du Petit-Château? ARCHIVES DELÉMONT Gare À Ne Pas Se Perdre Dans Le Swiss Labyrinthe PAGE 9

HUMANITAIRE En 150 ans, la Croix-Rouge s’est bonifiée PAGE 15 CYCLISME L’absurde épilogue du mont Ventoux PAGE 21 KEYSTONE VENDREDI 15 JUILLET 2016 | www.arcinfo.ch | N0 42367 | CHF 2.70 | J.A. - 2300 LA CHAUX-DE-FONDS Les fanfares devront aussi participer aux économies CONVENTION L’Etat va dénoncer ce texte qui OBJECTIF Le Département de l’éducation PROPOSITION Les deux parties espèrent octroie des tarifs préférentiels aux membres demande à son interlocuteur d’économiser conclure un nouvel accord. Peut-être de l’Association cantonale des musiques 80 000 francs pour la rentrée 2017. C’est trop, en coupant la poire en deux financièrement, neuchâteloises pour le Conservatoire. estime le président de l’association. pour satisfaire le plus grand nombre. PAGE 3 Qui sont ces serpents qui sifflent sur le Bois du Petit-Château? ARCHIVES DELÉMONT Gare à ne pas se perdre dans le Swiss Labyrinthe PAGE 9 GENS DU VOYAGE Petits travaux de peinture et plâtrerie fort contestés PAGE 8 MICROPOLLUANTS Petits et moyens cours d’eau particulièrement menacés PAGE 16 LA MÉTÉO DU JOUR pied du Jura à 1000m 11° 19° 6° 14° LUCAS VUITEL BOIS DU PETIT-CHÂTEAU Le vivarium du zoo chaux-de-fonnier met pour la première fois en vedette SOMMAIRE un serpent indigène: la vipère aspic. Quatre jeunes représentants d’une des deux seules espèces Télévision PAGE 12 Feuilleton PAGE 20 venimeuses de Suisse ont leur propre terrarium depuis hier. La revanche d’un animal mal aimé? PAGE 5 Jeux d’été PAGE 14 Carnet P. 2 6 - 2 7 PASSIONS ESTIVALES POÉSIE EN ARROSOIR A La Chaux-du-Milieu, Robin La poésie de Mahmoud cultive des rêves cuivrés Darwich résonne à Evologia Dans notre deuxième volet de notre série «Pourquoi as-tu laissé le cheval à sa soli- «Rêves de jeunesse», faisons connaissance tude?» Ce poème de Mahmoud Darwich avec Robin Fragnière, qui, à 17 ans, habite depuis des années la comédienne ne manque pas d’air. -

History of the National Flag of the United States of America

CR 113 HI8h THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES THE NATIONAL FLAG UNITED STATES OF AMERICA PHILADELPHIA, LIPPINCOTT, G R A M B a CO. 1853. HISTORY THE NATIONAL FLAG UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY SCHUYLER HAMILTON, CAPTAIN BY BREVET U. 8. A. PHILADELPHIA: LIPPIXCOTT, GRAMBO, AND CO. 1852. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1852, by LIPPIXCOTT, GRAMBO, AND CO., in the Office of the Clerk of the District Court of the United States in and for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania. PHILADELPHIA: T. K. AND P. G. COLLINS, PRINTERS. C/f THIS RESEARCH AS TO THE ORICIX AND MEAXIXC OF THE DEVICES COMBINED IX nf Bnitri of lje Rational /Ing tjjr Itatrs Jlratrirn, 13 RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED TO MAJOR-GENERAL WINFIELD SCOTT, AS .V SLIGHT THIin'TE OF RESPECT FOR HIS DISTIXC.UISHED SERVICES, AND AS A MARK OF PERSONAL (!1! ATITfDE, BT HIS FRIEND AND AIDE-DE-CAMP, SCHUYLER HAMILTON, Captain by Brevet, U. S. A. 860?^!* I PllEFACE. As nearly as we can learn, the only origin which has been suggested for the devices combined in the national colors of our country is, that they were adopted from the coat of arms of General Washing- ton. This imputed origin is not such as would be consonant with the known modesty of Washington, or the spirit of the times in which the flag was adopted. We have, therefore, been at some pains to collect authentic statements in reference to our national colors, and with these, have introduced letters exhibiting the temper of those times, step by step, with the changes made in the flag, so com- bining them as to form a chain of proof, which, we think, must be conclusive.