Crouching Masculinity, Hidden Risk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kopi Af Aktivlisten 2021-06-30 Ny.Xlsm

Velliv noterede aktier i alt pr. 30-06-2021 ISIN Udstedelsesland Navn Markedsværdi (i DKK) US0378331005 US APPLE INC 1.677.392.695 US5949181045 US MICROSOFT CORP 1.463.792.732 US0231351067 US AMAZON.COM INC 1.383.643.996 DK0060534915 DK NOVO NORDISK A/S-B 1.195.448.146 US30303M1027 US FACEBOOK INC-CLASS A 1.169.094.867 US02079K3059 US ALPHABET INC-CL A 867.740.769 DK0010274414 DK DANSKE BANK A/S 761.684.457 DK0060079531 DK DSV PANALPINA A/S 629.313.827 US02079K1079 US ALPHABET INC-CL C 589.305.120 US90138F1021 US TWILIO INC - A 514.807.852 US57636Q1040 US MASTERCARD INC - A 490.766.560 US4781601046 US JOHNSON & JOHNSON 478.682.981 US70450Y1038 US PAYPAL HOLDINGS INC 471.592.728 DK0061539921 DK VESTAS WIND SYSTEMS A/S 441.187.698 US79466L3024 US SALESFORCE.COM INC 439.114.061 US01609W1027 US ALIBABA GROUP HOLDING-SP ADR 432.325.255 US8835561023 US THERMO FISHER SCIENTIFIC INC 430.036.612 US22788C1053 US CROWDSTRIKE HOLDINGS INC - A 400.408.622 KYG875721634 HK TENCENT HOLDINGS LTD 397.054.685 KR7005930003 KR SAMSUNG ELECTRONICS CO LTD 389.413.700 DK0060094928 DK ORSTED A/S 378.578.374 ES0109067019 ES AMADEUS IT GROUP SA 375.824.429 US46625H1005 US JPMORGAN CHASE & CO 375.282.618 US67066G1040 US NVIDIA CORP 357.034.119 US17275R1023 US CISCO SYSTEMS INC 348.160.692 DK0010244508 DK AP MOLLER-MAERSK A/S-B 339.783.859 US20030N1019 US COMCAST CORP-CLASS A 337.806.502 NL0010273215 NL ASML HOLDING NV 334.040.559 CH0012032048 CH ROCHE HOLDING AG-GENUSSCHEIN 325.008.200 KYG970081173 HK WUXI BIOLOGICS CAYMAN INC 321.300.236 US4370761029 US HOME DEPOT INC 317.083.124 US58933Y1055 US MERCK & CO. -

Case 15-11663-LSS Doc 212 Filed 10/12/15 Page 1 of 109 Case 15-11663-LSS Doc 212 Filed 10/12/15 Page 2 of 109

Case 15-11663-LSS Doc 212 Filed 10/12/15 Page 1 of 109 Case 15-11663-LSS Doc 212 Filed 10/12/15 Page 2 of 109 EXHIBIT A Response Genetics, Inc. - U.S. CaseMail 15-11663-LSS Doc 212 Filed 10/12/15 Page 3 of 109 Served 10/9/2015 12 WEST CAPITAL MANAGEMENT LP 1727 JFK REALTY LP 3S CORPORATION 90 PARK AVENUE, 41ST FLOOR A PARTNERSHIP 1251 E. WALNUT NEW YORK, NY 10016 1727 JFK REALTY LLC CARSON, CA 90746 100 ENGLE ST CRESSKILL, NJ 07626-2269 4281900 CANADA INC. A C PHILLIPS AAAGENT SERVICES, LLC ATTN: DEBORAH DOLMAN 2307 CRESTVIEW ST 125 LOCUST ST. 100 RUE MARIE-CURIE THE VILLAGES, FL 32162-3455 HARRISBURG, PA 17101 DOLLARD-DES-ORMEAUX, QC H9A 3C6 CANADA AARON D SUMMERS AARON K BROTEN IRA TD AMERITRADE AARON WANG 202 S SUNNY SLOPE ST CLEARING CUSTODIAN 6880 SW 44TH ST #215 W FRANKFORT, IL 62896-3104 1820 PLYMOUTH LN UNIT 2 MIAMI, FL 33155-4765 CHANHASSEN, MN 55317-4837 AASHISH WAGLE ABBOTT MOLECULAR INC. ABBOTT MOLECULAR INC. 2220 W MISSION LN APT 1222 1300 EAST TOUHY AVENUE 75 REMITTANCE DRIVE SUTIE 6809 PHOENIX, AZ 85021 DES PLAINES, IL 60068 CHICAGO, IL 60675-6809 ABBOTT MOLECULAR INC. ABDUL BASIT BUTT ABE OFFICE FURNITURE OUTLET DIVISION COUNSEL 14 RENOIR DRIVE 3400 N. PECK RD. 1350 E. TOUHY AVE., STE 300W MONMOUTH JUNCTION, NJ 08852 EL MONTE, CA 91731 DES PLAINES, IL 60018 ABEDIN JAMAL ABEY M GEORGE ABHIJIT D NAIK 9253 REGENTS RD UNIT A207 3206 LOCHAVEN DR 1049 W OGDEN AVE LA JOLLA, CA 92037-9161 ROWLETT, TX 75088 APT 103 NAPERVILLE, IL 60563 ABRAHAM BROWN ACCENT - 1 ACCENT - 2 DESIGNATED BENE PLAN/TOD P.O. -

Portfolio Holdings Listing Fidelity Advisor Asset Manager 40% As Of

Portfolio Holdings Listing Fidelity Advisor Asset Manager 40% DUMMY as of July 30, 2021 The portfolio holdings listing (listing) provides information on a fund’s investments as of the date indicated. Top 10 holdings information (top 10 holdings) is also provided for certain equity and high income funds. The listing and top 10 holdings are not part of a fund’s annual/semiannual report or Form N-Q and have not been audited. The information provided in this listing and top 10 holdings may differ from a fund’s holdings disclosed in its annual/semiannual report and Form N-Q as follows, where applicable: With certain exceptions, the listing and top 10 holdings provide information on the direct holdings of a fund as well as a fund’s pro rata share of any securities and other investments held indirectly through investment in underlying non- money market Fidelity Central Funds. A fund’s pro rata share of the underlying holdings of any investment in high income and floating rate central funds is provided at a fund’s fiscal quarter end. For certain funds, direct holdings in high income or convertible securities are presented at a fund’s fiscal quarter end and are presented collectively for other periods. For the annual/semiannual report, a fund’s investments include trades executed through the end of the last business day of the period. This listing and the top 10 holdings include trades executed through the end of the prior business day. The listing includes any investment in derivative instruments, and excludes the value of any cash collateral held for securities on loan and a fund’s net other assets. -

RETAIL BANKING Americas DIGEST

Financial Services VOLUME III – SUMMER 2013 RETAIL BANKING AMERICAS DIGEST IN THIS ISSUE 1. SMALL BUSINESS BANKING Challenging Conventional Wisdom to Achieve Outsize Growth and Profitability 2. FINANCING SMALL BUSINESSES How “New-Form Lending” Will Reshape Banks’ Small Business Strategies 3. ENHANCED PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT Driving Breakthrough Productivity in Retail Banking Operations 4. INNOVatION IN MORtgagE OPERatIONS Building a Scalable Model 5. CHASE MERCHANT SERVICES How Will it Disrupt the Card Payments Balance of Power? 6. THE FUTURE “AR Nu” What We Can Learn from Sweden About the Future of Retail Distribution FOREWORD Banking is highly regulated, intensely competitive and provides products that, while omnipresent in consumers’ lives, are neither top-of-mind nor enticing to change. These factors drive the role and form of innovation the industry can capitalize on. In traditional business history – the realm of auto manufacturers, microchip makers, logistics companies and retailers – the literature rightly hails disruptive, game-changing innovation as the engine behind outsized profits for the first movers. In banking, such innovation is very rare. Disruptive innovations of the magnitude of the smartphone or social networking grab headlines, but are hard to leverage in the banking industry. There are simply too many restrictions on what banks can do, and too much consumer path dependency, to place all the shareholders’ chips on disruptive innovation plays. Instead, successful banks develop and execute strategies around less “flashy”, -

SA FUNDS INVESTMENT TRUST Form N-Q Filed 2016-11-23

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM N-Q Quarterly schedule of portfolio holdings of registered management investment company filed on Form N-Q Filing Date: 2016-11-23 | Period of Report: 2016-09-30 SEC Accession No. 0001206774-16-007593 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER SA FUNDS INVESTMENT TRUST Mailing Address Business Address 10 ALMADEN BLVD, 15TH 10 ALMADEN BLVD, 15TH CIK:1075065| IRS No.: 770216379 | State of Incorp.:DE | Fiscal Year End: 0630 FLOOR FLOOR Type: N-Q | Act: 40 | File No.: 811-09195 | Film No.: 162016544 SAN JOSE CA 95113 SAN JOSE CA 95113 (800) 366-7266 Copyright © 2016 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM N-Q QUARTERLY SCHEDULE OF PORTFOLIO HOLDINGS OF REGISTERED MANAGEMENT INVESTMENT COMPANY Investment Company Act file number: 811-09195 SA FUNDS - INVESTMENT TRUST (Exact name of registrant as specified in charter) 10 Almaden Blvd., 15th Floor, San Jose, CA 95113 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Deborah Djeu Chief Compliance Officer SA Funds - Investment Trust 10 Almaden Blvd., 15th Floor, San Jose, CA 95113 (Name and Address of Agent for Service) Copies to: Brian F. Link Mark D. Perlow, Esq. Vice President and Managing Counsel Counsel to the Trust State Street Bank and Trust Company Dechert LLP 100 Summer Street One Bush Street, Suite 1600 7th Floor, Mailstop SUM 0703 San Francisco, CA 94104-4446 Boston, MA 02111 Registrants telephone number, including area code: (800) 366-7266 Date of fiscal year end: June 30 Date of reporting period: September 30, 2016 Copyright © 2013 www.secdatabase.com. -

Nordnet Invests in Real-Time Analytics to Evolve End-User Support

NEXTHINK SUCCESS STORY Nordnet Invests in Real-Time Analytics to Evolve End-User Support ORGANIZATION Nordnet selected Nexthink to deliver reliable IT analytics in real-time, from the end- Nordnet user perspective. The solution is a good fit to empower proactive rather than reactive IT support within the organisation. INDUSTRY Finance CONTEXT LOCATION Founded in 1996, Nordnet Bank AB is an evolution of the consumer banking Sweden concept. By empowering clients to conduct a wide variety of digital transactions, Nordnet has made significant inroads on its vision to become the number one KEY CHALLENGES choice for savings and investments in the Nordics. z Need for a robust and agile solution that could deliver reliable IT analytics in real-time z To ensure IT staff have access to critical end-user data on demand and keep critical information secure z To empower proactive rather than reactive IT support According to CEO Håkan Nyberg, completing this journey demands a combina- tion of transparency and customer satisfaction. Specifically, Nordnet aims to increase their active customer base by 10 percent each year and ensure annual net savings are at least ten percent of the savings capital at the start of the year. So far, it’s working: the bank now supplies investment, savings and loan services to users in Sweden, Norway, Denmark and Finland and is publicly traded on the Nasdaq Stockholm Exchange. Smarter IT through analytics www.nexthink.com “We needed a solution to get CHALLENGES data from end-users to see what’s Nordnet’s strive for continued growth depends in large part on the reliability happening.” and security of its digital service platform — if the customers can’t log in they are Mikael Koch unable to manage their portfolio or view projected investment growth. -

WORLD RETAIL BANKING REPORT 2015 Contents

WORLD RETAIL BANKING REPORT 2015 Contents 3 Preface 5 Chapter 1: Stagnating Customer Experience and Deteriorating Profitable Customer Behaviors 6 Overall Customer Experience Levels Stagnated, but Extreme Ends of Positive and Negative Experiences Increased 9 Growth of Low-Cost Channels Fails to Displace Branch Usage 12 Customer Behaviors Impacting Banks’ Profitability 17 Chapter 2: Competitive Threats Disrupting the Banking Landscape 18 Growing Competition across Products and Lifecycle Stages 22 Threat from FinTech Firms As They Gain Customers’ Trust 25 Chapter 3: Lagging Middle- and Back-Office Investments Drag Down Customer Experience 26 Need to Bring the Focus Back to Middle- and Back-Offices 28 The Way Forward 30 Conclusion 31 Appendix 33 Methodology 34 About Us 35 Acknowledgements Preface Retail banking customers today have more choices than ever before in terms of where, when, and how they bank—making it critical for financial institutions to present options that appeal directly to their customers’ desires and expectations. Now in its 12th year, the 2015 World Retail Banking Report (WRBR), published by Capgemini and Efma, offers detailed insight into the specific types of experiences customers are seeking when they engage with their banks, making it an invaluable resource for developing strategies to combat an ever-widening array of competitors. Drawing on one of the industry’s largest customer experience surveys—including responses from over 16,000 customers across 32 countries, as well as in-depth executive interviews—the 2015 WRBR sheds light on critical performance metrics for the industry, such as the likelihood of customers to leave their bank or purchase additional products. -

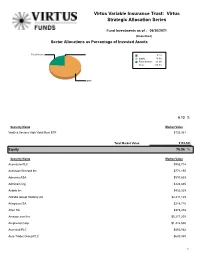

Virtus Variable Insurance Trust: Virtus Strategic Allocation Series

Virtus Variable Insurance Trust: Virtus Strategic Allocation Series Fund Investments as of : 06/30/2021 (Unaudited) Sector Allocations as Percentage of Invested Assets Fixed Income 0.1% Equity 76.0% Fixed Income 23.9% Total: 100.0% Equity 0.13 % Security Name Market Value VanEck Vectors High Yield Muni ETF $133,581 Total Market Value: $133,581 Equity 75.96 % Security Name Market Value Accenture PLC $983,714 Activision Blizzard Inc $771,155 Adevinta ASA $591,633 Admicom Oyj $123,695 Airbnb Inc $452,529 Alibaba Group Holding Ltd $2,411,125 Allegro.eu SA $218,716 Alten SA $378,478 Amazon.com Inc $5,277,205 Amphenol Corp $1,412,530 Ascential PLC $450,562 Auto Trader Group PLC $639,885 1 Autohome Inc $190,921 Avalara Inc $1,929,141 Bank of America Corp $1,237,477 Bill.com Holdings Inc $4,665,595 Boa Vista Servicos SA $227,428 Bouvet ASA $304,957 Brockhaus Capital Management AG $137,235 BTS Group AB $418,294 CAE Inc $506,141 Cerved Group SpA $153,342 CME Group Inc $550,841 Corp Moctezuma SAB de CV $192,124 CoStar Group Inc $1,162,793 CTS Eventim AG & Co KGaA $159,410 CTT Systems AB $266,966 Danaher Corp $1,307,182 DocuSign Inc $658,946 Duck Creek Technologies Inc $1,267,664 Ecolab Inc $700,710 Enento Group Oyj $373,228 Equifax Inc $624,882 Estee Lauder Cos Inc/The $743,671 Facebook Inc $3,836,284 Fair Isaac Corp $741,956 FDM Group Holdings PLC $207,920 Fineos Corp Ltd $70,397 Fintel Plc $473,852 Frontera Energy Corp $6,746 Gruppo MutuiOnline SpA $385,818 Haitian International Holdings Ltd $147,624 Haw Par Corp Ltd $416,695 HeadHunter Group -

The 2008 Icelandic Bank Collapse: Foreign Factors

The 2008 Icelandic Bank Collapse: Foreign Factors A Report for the Ministry of Finance and Economic Affairs Centre for Political and Economic Research at the Social Science Research Institute University of Iceland Reykjavik 19 September 2018 1 Summary 1. An international financial crisis started in August 2007, greatly intensifying in 2008. 2. In early 2008, European central banks apparently reached a quiet consensus that the Icelandic banking sector was too big, that it threatened financial stability with its aggressive deposit collection and that it should not be rescued. An additional reason the Bank of England rejected a currency swap deal with the CBI was that it did not want a financial centre in Iceland. 3. While the US had protected and assisted Iceland in the Cold War, now she was no longer considered strategically important. In September, the US Fed refused a dollar swap deal to the CBI similar to what it had made with the three Scandinavian central banks. 4. Despite repeated warnings from the CBI, little was done to prepare for the possible failure of the banks, both because many hoped for the best and because public opinion in Iceland was strongly in favour of the banks and of businessmen controlling them. 5. Hedge funds were active in betting against the krona and the banks and probably also in spreading rumours about Iceland’s vulnerability. In late September 2008, when Glitnir Bank was in trouble, the government decided to inject capital into it. But Glitnir’s major shareholder, a media magnate, started a campaign against this trust-building measure, and a bank run started. -

Notice to the Annual General Meeting 2021 of Nordnet AB (Publ)

Convenience translation, Swedish version shall prevail Notice to the Annual General Meeting of Nordnet AB (publ) Shareholders of Nordnet AB (publ), reg. nr 559073-6681, (the "Company” or ”Nordnet”) are hereby invited to attend the Annual General Meeting on 29 April 2021. Due to the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, the Board has decided to conduct the Annual General Meeting as a meeting with only postal voting in accordance with Section 20 of the Act (2020:198) on temporary exceptions to facilitate the execution of general meetings in companies and other associations. This means that the meeting is conducted without the physical presence of shareholders, proxies and third parties and that shareholders can exercise their voting rights only through postal voting as specified under the heading Postal voting below. The Company will also arrange a digital event on Monday 26 April 2021 at 16:00 CET, where shareholders have the opportunity to listen to senior executives and ask questions. Information about this event will be published shortly. Right to attend and notice Anyone wishing to participate in the meeting shall be registered in the shareholders' register maintained by Euroclear Sweden AB on 21 April 2021, and shall notify the Company of their intention to attend the meeting by casting their postal vote, in accordance with the instructions under the heading Postal voting below, in such time that the postal vote is received by Euroclear Sweden AB no later than on 28 April 2021. Nominee-registered shares In order to participate in the Annual General Meeting, shareholders whose shares are nominee-registered must, in addition to casting their postal vote, ensure that they are entered in the share register in their own name as of 21 April 2021. -

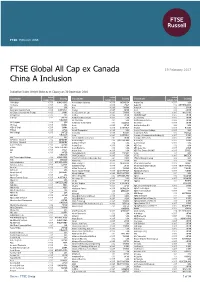

FTSE Global All Cap Ex Canada China a Inclusion

FTSE PUBLICATIONS FTSE Global All Cap ex Canada 19 February 2017 China A Inclusion Indicative Index Weight Data as at Closing on 30 December 2016 Index Index Index Constituent Country Constituent Country Constituent Country weight (%) weight (%) weight (%) 13 Holdings <0.005 HONG KONG Ace Hardware Indonesia <0.005 INDONESIA Aegion Corp. <0.005 USA 1st Source <0.005 USA Acea <0.005 ITALY Aegon NV 0.02 NETHERLANDS 2U <0.005 USA Acer <0.005 TAIWAN Aena S.A. 0.02 SPAIN 360 Capital Industrial Fund <0.005 AUSTRALIA Acerinox <0.005 SPAIN Aeon 0.02 JAPAN 361 Degrees International (P Chip) <0.005 CHINA Aces Electronic Co. Ltd. <0.005 TAIWAN Aeon (M) <0.005 MALAYSIA 3-D Systems <0.005 USA Achilles <0.005 JAPAN AEON DELIGHT <0.005 JAPAN 3i Group 0.02 UNITED Achillion Pharmaceuticals <0.005 USA Aeon Fantasy <0.005 JAPAN KINGDOM ACI Worldwide 0.01 USA AEON Financial Service <0.005 JAPAN 3M Company 0.26 USA Ackermans & Van Haaren 0.01 BELGIUM Aeon Mall <0.005 JAPAN 3S Korea <0.005 KOREA Acom <0.005 JAPAN AerCap Holdings N.V. 0.02 USA 3SBio (P Chip) <0.005 CHINA Aconex <0.005 AUSTRALIA Aeroflot <0.005 RUSSIA 77 Bank <0.005 JAPAN Acorda Therapeutics <0.005 USA Aerojet Rocketdyne Holdings <0.005 USA 888 Holdings <0.005 UNITED Acron JSC <0.005 RUSSIA Aeroports de Paris 0.01 FRANCE KINGDOM Acrux <0.005 AUSTRALIA Aerospace Communications Holdings (A) <0.005 CHINA 8x8 <0.005 USA ACS Actividades Cons y Serv 0.01 SPAIN Aerospace Hi-Tech (A) <0.005 CHINA A P Moller - Maersk A 0.02 DENMARK Actelion Hldg N 0.05 SWITZERLAND Aerosun (A) <0.005 CHINA A P Moller - Maersk B 0.02 DENMARK Activision Blizzard 0.06 USA AeroVironment <0.005 USA A.G.V. -

Developing Components for a Data- Driven Trading System

Developing components for a data- driven trading system Bachelor’s thesis in Computer Science and Engineering FRED HEDENBERG Department of Computer Science and Engineering CHALMERS UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF GOTHENBURG Gothenburg, Sweden 2018 DEGREE PROJECT REPORT Developing components for a data-driven trading system FRED HEDENBERG Department of Computer Science and Engineering CHALMERS UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF GOTHENBURG Gothenburg, Sweden 2018 Developing components for a data-driven trading system FRED HEDENBERG © FRED HEDENBERG, 2018 Examiner: Peter Lundin Department of Computer Science and Engineering Chalmers University of Technology / University of Gothenburg SE-412 96 Göteborg Sweden Telephone: +46 (0)31-772 1000 The Author grants to Chalmers University of Technology and University of Gothenburg the non-exclusive right to publish the Work electronically and in a non-commercial purpose make it accessible on the Internet. The Author warrants that he/she is the author to the Work, and warrants that the Work does not contain text, pictures or other material that violates copyright law. The Author shall, when transferring the rights of the Work to a third party (for example a publisher or a company), acknowledge the third party about this agreement. If the Author has signed a copyright agreement with a third party regarding the Work, the Author warrants hereby that he/she has obtained any necessary permission from this third party to let Chalmers University of Technology and University of Gothenburg store the Work electronically and make it accessible on the Internet. Cover: This visualization is meant to communicate a summarized view of how the price develops over a set of events.