The Case of Lasiodiplodia Theobromae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vegetative and Reproductive Phenology of Aquilaria Malaccensis Lam

OPEN ACCESS The Journal of Threatened Taxa is dedicated to building evidence for conservation globally by publishing peer-reviewed articles online every month at a reasonably rapid rate at www.threatenedtaxa.org. All articles published in JoTT are registered under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License unless otherwise mentioned. JoTT allows unrestricted use of articles in any medium, reproduction, and distribution by providing adequate credit to the authors and the source of publication. Journal of Threatened Taxa Building evidence for conservation globally www.threatenedtaxa.org ISSN 0974-7907 (Online) | ISSN 0974-7893 (Print) Communication Vegetative and reproductive phenology of Aquilaria malaccensis Lam. (Agarwood) in Cachar District, Assam, India Birkhungur Borogayary, Ashesh Kumar Das & Arun Jyoti Nath 26 July 2018 | Vol. 10 | No. 8 | Pages: 12064–12072 10.11609/jott.3825.10.8.12064-12072 For Focus, Scope, Aims, Policies and Guidelines visit http://threatenedtaxa.org/index.php/JoTT/about/editorialPolicies#custom-0 For Article Submission Guidelines visit http://threatenedtaxa.org/index.php/JoTT/about/submissions#onlineSubmissions For Policies against Scientific Misconduct visit http://threatenedtaxa.org/index.php/JoTT/about/editorialPolicies#custom-2 For reprints contact <[email protected]> Threatened Taxa Vegetative and reproductive phenology ofAquilaria Journal malaccensis of Threatened Taxa | www.threatenedtaxa.org | 26 July 2018 | 10(8): 12064–12072Borogayary et al. Vegetative and reproductive phenology -

University of Khartoum Graduate College Medical and Health Studies Board Activity

University of Khartoum Graduate College Medical and Health Studies Board Activity- guided Isolation and Structure Determination of Antioxidant and Antidiabetic Compounds from Bauhinia rufescence L. By: Wadah Jamal Ahmed Osman B. Pharm. U of K. (2003) M. Pharm. King Saud University (2012) A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of PhD in Pharmacognosy Supervisor Prof.Abdelkhaleig Muddathir, (B.Pharm.M.pharm., PhD) Professor of Pharmacognosy, U.of K. 2014 I Co-Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Hassan Elsubki Khalid B.Pharm., PhD Professor of Pharmacognosy, U.of K. II DEDICATION First of all I thank Almighty Alla for his mercy and wide guidance on a completion of my study. This thesis is dedicated to my parents, who taught me the value of education, to my beloved wife and to my beautiful kids. I express my warmest gratitude to my supervisor Professor Dr Prof. Abdelkhaleig Muddathir and Prof. Dr. Hassan Elsubki for their support, valuable advice, excellent supervision and accurate and abundant comments on the manuscripts taught me a great deal of scientific thinking and writing. In addition, I would like to express my appreciation to all members of the Pharmacognosy Department for their encouragement, support and help throughout this study. Great thanks for Professor Kamal Eldeen El Tahir (King Saud University, Riyadh) and Prof. Sayeed Ahmed (Jamia Hamdard University, India) for their co-operation and scientific support during the laboratory work. Wadah jamal Ahmed July, 2018 III Contents 1. Introduction and Literature review 1.1.Oxidative Stress and Reactive Metabolites 1 1.2. Production Of reactive metabolites 1 1.3. -

Comparative Morpho-Micrometric Analysis of Some Bauhinia Species (Leguminosae) from East Coast Region of Odisha, India

Indian Journal of Natural Products and Resources Vol. 11(3), September 2020, pp. 169-184 Comparative morpho-micrometric analysis of some Bauhinia species (Leguminosae) from east coast region of Odisha, India Pritipadma Panda1, Sanat Kumar Bhuyan2, Chandan Dash3, Deepak Pradhan3, Goutam Rath3 and Goutam Ghosh3* 1Esthetic Insights Pvt. Ltd., Plot No: 631, Rd Number 1, KPHB Phase 2, Kukatpally, Hyderabad, Telangana 500072, India 2Institute of Dental Sciences, 3School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Siksha ‗O‘ Anusandhan (Deemed to be University), Bhubaneswar, Odisha 751003, India Received 18 May 2018; Revised 19 May 2020 Bauhinia vahlii has been reported for several medicinal properties, such as tyrosinase inhibitory, immunomodulatory and free radical scavenging activities. Bauhinia tomentosa and Bauhinia racemosa also possess anti-diabetic, anticancer, antidiabetic, anti-obesity and antihyperlipidemic activities. Therefore, the correct identification of these plants is critically important. The aim was to investigate the comparative morpho-micrometric analysis of 3 species of Bauhinia belonging to the family Leguminosae (Fabaceae) by using conventional as well as scanning electron microscopy to support species identification. In B. racemosa, epidermal cells are polygonal with anticlinical walls; whereas wavy walled cells are found in B. tomentosa and B. vahlii. Anisocytic stomata are present in B. racemosa, while B. tomentosa shows the presence of paracytic stomata and anomocytic stomata in B. vahlii. Stomatal numbers and stomatal indices were found to be more in B. vahlii than B. tomentosa and B. racemosa. On the other hand, uniseriate, unicellular covering trichomes are found in B. racemosa and B. tomentosa but B. vahlii contains only uniseriate, multicellular covering trichomes. Based on these micromorphological features, a diagnostic key was developed for identification of the particular species which helps a lot in pharmaceutical botany, taxonomy and horticulture, in terms of species identification. -

261 Comparative Morphology and Anatomy of Few Mangrove Species

261 International Journal of Bio-resource and Stress Management 2012, 3(1):001-017 Comparative Morphology and Anatomy of Few Mangrove Species in Sundarbans, West Bengal, India and its Adaptation to Saline Habitat Humberto Gonzalez Rodriguez1, Bholanath Mondal2, N. C. Sarkar3, A. Ramaswamy4, D. Rajkumar4 and R. K. Maiti4 1Facultad de Ciencias Forestales, Universidad Autonoma de Nuevo Leon, Carr. Nac. No. 85, Km 145, Linares, N.L. Mexico 2Department of Plant Protection, Palli Siksha Bhavana, Visva-Bharati, Sriniketan (731 236), West Bengal, India 3Department of Agronomy, SASRD, Nagaland University, Medziphema campus, Medziphema (PO), DImapur (797 106), India 4Vibha Seeds, Inspire, Plot#21, Sector 1, Huda Techno Enclave, High Tech City Road, Madhapur, Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh (500 081), India Article History Abstract Manuscript No. 261 Mangroves cover large areas of shoreline in the tropics and subtropics where they Received in 30th January, 2012 are important components in the productivity and integrity of their ecosystems. High Received in revised form 9th February, 2012 variability is observed among the families of mangroves. Structural adaptations include Accepted in final form th4 March, 2012 pneumatophores, thick leaves, aerenhyma in root helps in surviving under flooded saline conditions. There is major inter- and intraspecific variability among mangroves. In this paper described morpho-anatomical characters helps in identification of family Correspondence to and genus and species of mangroves. Most of the genus have special type of roots which include Support roots of Rhizophora, Pnematophores of Avicennia, Sonneratia, Knee *E-mail: [email protected] roots of Bruguiera, Ceriops, Buttress roots of Xylocarpus. Morpho-anatomically the leaves show xerophytic characteristics. -

Cites Cites Listings of Tropical Tree Species

Issue Number 2-9 May 2015 ITTO - PROGRAM FOR IMPLEMENTING CITES CITES LISTINGS OF TROPICAL TREE SPECIES Newsletter This Newsletter reports on activities under the second phase of the ITTO-CITES Program for Implementing CITES Listings of Tropical Tree Species. Following up on the successful first phase In this of the Program (2007-2011), this second phase is continuing work during 2012-2016 on the most important CITES-listed tropical tree species in trade. The Program is majority-funded through a grant from the European Union (via the European Commission), which also provides for part of the Issue available funds to be devoted to activities relevant to both the ITTO-CITES Program and the ITTO Thematic Program on Trade and Market Transparency (TMT). The Newsletter is published on a EDITORIAL ............................. 1 quarterly basis, in English, French and Spanish, and is made available to all Program stakeholders ITTO-CITES PROGRAM ........... 2 and other individuals interested in the progress of the ITTO–CITES Program. This issue covers a PROGRAM FUNDING ............ 2 summary of the Program activities up to April 2015. ACTIVITY PROGRESS Suggestions and contributions from Program stakeholders are essential to make future issues of REPORTS ................................. 2 this Newsletter as informative and interesting as possible. Please send any correspondence to the RELEVANT EVENTS/ relevant contact(s) listed on the last page. INITIATIVES ......................... 13 ARTICLE OF INTEREST .......... 14 UPCOMING EVENTS ........... -

CITES Appendix II

PC20 Inf. 7 Annex 9 INTRODUCTION TO CITES AND AGARWOOD OVERVIEW Asian Regional Workshop on Agarwood; 22-24 November 2011 By Milena Sosa Schmidt, CITES Secretariat: [email protected] A bit of history Several genera from the family Thymeleaceae are agarwood producing taxa. These are: Aquilaria, Enkleia, Aetoxylon, Gonystylus, Wikstroemia, Gyrinops. They produce different qualities of agarwood from which Aquilaria seems to be the best (see Indonesia report of 2003). From these six genera we have currently three listed on CITES Appendix II. The history of these listings is as follows: THYMELAEACEAE (AQUILARIACEAE) (E) Agarwood, ramin; (S) Madera de Agar, ramin; (F) Bois d'Agar, ramin Aquilaria spp. II 12/01/05 #1CoP13 II/r AE 12/01/05 Excludes Aquilaria malaccensis. Excluye Aquilaria malaccensis. Exclus Aquilaria malaccensis. II/r KW 12/01/05 Excludes Aquilaria malaccensis. Excluye Aquilaria malaccensis. Exclus Aquilaria malaccensis. II/r QA 12/01/05 Excludes Aquilaria malaccensis. Excluye Aquilaria malaccensis. Exclus Aquilaria malaccensis. II/r SY 12/01/05 Excludes Aquilaria malaccensis. Excluye Aquilaria malaccensis. Exclus Aquilaria malaccensis. II 13/09/07 #1CoP14 II 23/06/10 #4CoP15 Aquilaria malaccensis II 16/02/95 #1CoP9 II 12/01/05 Included in Aquilaria spp. Incluida en Aquilaria spp. Inclus dans Aquilaria spp. Gonystylus spp. III ID 06/08/01 #1CoP11 III/r MY 17/08/01 II 12/01/05 #1CoP13 II/r MY 12/01/05 II/w MY 07/06/05 II 13/09/07 #1CoP14 II 23/06/10 #4CoP15 Gyrinops spp. II 12/01/05 #1CoP13 II/r AE 12/01/05 II/r KW 12/01/05 II/r QA 12/01/05 II/r SY 12/01/05 II 13/09/07 #1CoP14 II 23/06/10 #4CoP15 The current annotation for these taxa is #4 and reads: All parts and derivatives, except: 1 PC20 Inf. -

Anogeissus Acuminata (Roxb) Wall Ex Bedd in Vitro

International Journal of Complementary & Alternative Medicine Review Article Open Access Detection of free radical scavenging activity of dhaura, anogeissus acuminata (roxb) wall ex bedd in vitro Abstract Volume 12 Issue 4 - 2019 The free radical inhibitory activity of Dhaura, Anogeissus acuminata extracted in chloroform, ethanol and water was investigated in vitro. The DPPH inhibition by the Ganesh Chandra Jagetia, Zairempuii different stem extract depended on the concentration and the ethanol extract was found Department of Zoology, Mizoram University, India to be the most potent as the lower concentration of it was most effective in scavenging Correspondence: Ganesh Chandra Jagetia, Department of different free radicals. The analysis of superoxide radical scavenging activity showed that Zoology, Mizoram University, India, Email the aqueous extract was most effective when compared to chloroform and ethanol extracts. The different extracts of Dhaura also inhibited the generation of nitric oxide radical Received: August 5, 2019 | Published: August 27, 2019 depending on its concentration and maximum effect was observed at 200μg/ml. Our study indicates that free radical scavenging activity of Dhaura affirms the medicinal use by the practitioners of folklore medicine. Keywords: anogeissus acuminata, DPPH, superoxide, nitric oxide, endoplasmic reticulum, peroxisomes, mitochondria Abbreviations: EDTA, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid; enlargement of spleen cold, dysuria, cough, excessive perspiration, 15 NBT, nitrobluetetrazolium; TCA, trichloroacetic acid; NED, N–(1– cholera, urinary disorders, snake bite and in scorpion sting. The Naphthyl)ethylenediamine dihydrochloride gum produced by Dhaura is called Ghatti or Indian gum and is used as a tonic after delivery.15,16 The preclinical studies have shown the Introduction alleviation of alloxan–induced diabetes in rats.17. -

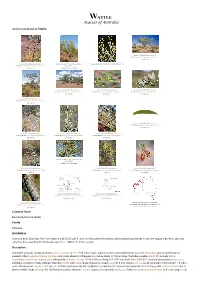

Acacia Synchronicia Maslin

WATTLE Acacias of Australia Acacia synchronicia Maslin Source: W orldW ideW attle ver. 2. Published at: w w w .w orldw idew attle.com B.R. Maslin Source: W orldW ideW attle ver. 2. Source: Australian Plant Image Index Image courtesy of Northern Territory Herbarium Published at: w w w .w orldw idew attle.com (dig.15818). B.R. Maslin ANBG © M. Fagg, 2009 Source: W orldW ideW attle ver. 2. Source: W orldW ideW attle ver. 2. Source: W orldW ideW attle ver. 2. Published at: w w w .w orldw idew attle.com Published at: w w w .w orldw idew attle.com Published at: w w w .w orldw idew attle.com B.R. Maslin B.R. Maslin B.R. Maslin Source: W orldW ideW attle ver. 2. Published at: w w w .w orldw idew attle.com B.R. Maslin Source: W orldW ideW attle ver. 2. Published at: w w w .w orldw idew attle.com Kym Brennan Source: W orldW ideW attle ver. 2. Source: W orldW ideW attle ver. 2. Source: W orldW ideW attle ver. 2. Published at: w w w .w orldw idew attle.com Published at: w w w .w orldw idew attle.com Published at: w w w .w orldw idew attle.com B.R. Maslin B.R. Maslin B.R. Maslin Source: Australian Plant Image Index (dig.15819). ANBG © M. Fagg, 2009 Source: W orldW ideW attle ver. 2. Source: W orldW ideW attle ver. 2. Source: W orldW ideW attle ver. 2. Published at: w w w .w orldw idew attle.com Published at: w w w .w orldw idew attle.com Published at: w w w .w orldw idew attle.com J. -

Analgesic Effects of Methanolic Extracts of Anogeissus Latifolia Wall on Swiss Albino Mice

Available online a t www.pelagiaresearchlibrary.com Pelagia Research Library Der Pharmacia Sinica, 2013, 4(5):79-82 ISSN: 0976-8688 CODEN (USA): PSHIBD Analgesic effects of methanolic extracts of Anogeissus latifolia wall on swiss albino mice Vijusha M.*1, Shalini K.2, Veeresh K.2, Rajini A.2 and Hemamalini K.1 1Teegala Ram Reddy College of Pharmacy, Meerpet, Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh, India 2Sree Dattha Institute of Pharmacy, Sheriguda, Ibrahimpatnam, Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh, India _____________________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT The main objective of my present research work is to find out the good pharmacological properties from medicinal plants with their preliminary phytochemical study and also to evaluate the analgesic activity of Anogeissus latifolia belongs to combretaceae family on mice by tail immersion, tail flick and eddy’s hot plate method. Dose was selected from the literature and the dose chosen for the study is 200 mg/kg, a small trial on acute toxicity was used to confirm the dose by using 2000 mg/kg, and there was no mortality found, so 1/10 th of this dose was chosen for analgesic activity. Normally herbal drugs are free of side effects and available in low cost. The methanolic extract of Anogeissus latifolia at 200 mg/kg showed a significant analgesic activity in tail immersion, tail flick, and hot plate model when compared to that of standard drug. Key words: Anogeissus latifolia, leaf, methanolic extract, tail immersion, tail flick and eddy’s hot plate model. _____________________________________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION In the history of medicine for the relief of pain many medicinal herbs has been used .natural products which contain many active principles are believed to have their potiential therapeutic value. -

Phylogenetic Relationships Among the Mangrove Species of Acanthaceae Found in Indian Sundarban, As Revealed by RAPD Analysis

Available online a t www.pelagiaresearchlibrary.com Pelagia Research Library Advances in Applied Science Research, 2015, 6(3):179-184 ISSN: 0976-8610 CODEN (USA): AASRFC Phylogenetic relationships among the mangrove species of Acanthaceae found in Indian Sundarban, as revealed by RAPD analysis Surya Shekhar Das 1, Swati Das (Sur) 2 and Parthadeb Ghosh* 1Department of Botany, Bolpur College, Birbhum, West Bengal, India 2Department of Botany, Nabadwip Vidyasagar College, Nadia, West Bengal, India _____________________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT RAPD markers were successfully used to identify and differentiate all the five species of Acanthaceae found in the mangrove forest of Indian Sundarban, to assess the extent of interspecific genetic diversity among them, to reveal their molecular phylogeny and to throw some light on the systematic position of Avicennia. The dendrogram reveals that the five species under study exhibits an overall similarity of 60.7%. Avicennia alba and A. officinalis (cluster C1) have very close relationship between them and share a common node in the dendrogram at a 73.3% level of similarity. Avicennia marina and Acanthus ilicifolius (cluster C2) also have close relationship between them as evident by a common node in the dendrogram at 71.8% level of similarity. Acanthus volubilis showed 68.1% similarity with cluster C1 and 60.7% similarity with cluster C2. Our study also supported the view of placing Avicennia under Acanthaceae. Regarding the relative position of Avicennia within Acanthaceae, it was shown to be very close to Acanthoideae. In comparison to other species, A. marina showed most genetic variability, suggesting utilization of this species over others for breeding programme and as source material in in situ conservation programmes. -

Acacia Glaucocaesia Domin

WATTLE Acacias of Australia Acacia glaucocaesia Domin Source: W orldW ideW attle ver. 2. Source: W orldW ideW attle ver. 2. Source: W orldW ideW attle ver. 2. Source: W orldW ideW attle ver. 2. Published at: w w w .w orldw idew attle.com Published at: w w w .w orldw idew attle.com Published at: w w w .w orldw idew attle.com Published at: w w w .w orldw idew attle.com B.R. Maslin B.R. Maslin B.R. Maslin B.R. Maslin Source: W orldW ideW attle ver. 2. Source: W orldW ideW attle ver. 2. Source: W orldW ideW attle ver. 2. Published at: w w w .w orldw idew attle.com Published at: w w w .w orldw idew attle.com Published at: w w w .w orldw idew attle.com B.R. Maslin J. Maslin B.R. Maslin Source: W orldW ideW attle ver. 2. Published at: w w w .w orldw idew attle.com B.R. Maslin Source: W orldW ideW attle ver. 2. Published at: w w w .w orldw idew attle.com See illustration. Source: W orldW ideW attle ver. 2. Acacia glaucocaesia occurrence map. Published at: w w w .w orldw idew attle.com O ccurrence map generated via Atlas of Living B.R. Maslin Australia (https://w w w .ala.org.au). Family Fabaceae Distribution Known only from a few scattered localities in the western part of the Pilbara region mainly between the Fortescue and De Grey Rivers, including North Turtle Is., north- western W.A. A sterile specimen with persistent, spinose stipules, collected from a regrowth population at Salt Ck, between Port Hedland and Broome (B.R.Maslin 4874, PERTH), is tentatively referred to this species: see B.R.Maslin, Nuytsia 8: 298 (1992), for discussion. -

Cintia Luz.Pdf

Cíntia Luíza da Silva Luz Filogenia e sistemática de Schinus L. (Anacardiaceae), com revisão de um clado endêmico das matas nebulares andinas Phylogeny and systematics of Schinus L. (Anacardiaceae), with revision of a clade endemic to the Andean cloud forests Tese apresentada ao Instituto de Biociências da Universidade de São Paulo, para obtenção de Título de Doutor em Ciências, na Área de Botânica. Orientador: Dr. José Rubens Pirani São Paulo 2017 Luz, Cíntia Luíza da Silva Filogenia e sistemática de Schinus L. (Anacardiaceae), com revisão de um clado endêmico das matas nebulares andinas Número de páginas: 176 Tese (Doutorado) - Instituto de Biociências da Universidade de São Paulo. Departamento de Botânica. 1. Anacardiaceae 2. Schinus 3. Filogenia 4. Taxonomia vegetal I. Universidade de São Paulo. Instituto de Biociências. Departamento de Botânica Comissão julgadora: ______________________________ ______________________________ Prof(a). Dr.(a) Prof(a). Dr.(a) ______________________________ ______________________________ Prof(a). Dr.(a) Prof(a). Dr.(a) _____________________________________ Prof. Dr. José Rubens Pirani Orientador Ao Luciano Luz, pelo entusiasmo botânico, companheirismo e dedicação aos Schinus Esta é a estória. Ia um menino, com os tios, passar dias no lugar onde se construía a grande cidade. Era uma viagem inventada no feliz; para ele, produzia-se em caso de sonho. Saíam ainda com o escuro, o ar fino de cheiros desconhecidos. A mãe e o pai vinham trazê-lo ao aeroporto. A tia e o tio tomavam conta dele, justínhamente. Sorria-se, saudava-se, todos se ouviam e falavam. O avião era da companhia, especial, de quatro lugares. Respondiam-lhe a todas as perguntas, até o piloto conversou com ele.