ANNEX 6 COMMENTARY on the CONSULTATION DOCUMENT in This Annex 6 of Sky's Response We Provide a Non-Exhaustive List of the Erro

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

We're Making It Easier to Find Your Favourite Shows

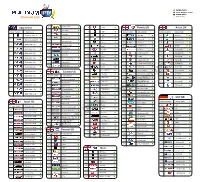

We’re making it easier to find your favourite shows Here’s a quick rundown of the changes we’re introducing: • Documentary channels will be moved up the TV Guide to sit alongside Entertainment channels • +1 channels will be listed in a new menu on the TV Guide • +1s from Entertainment & Documentaries move to new linked channel numbers (e.g, Sky One - 106, Sky One+1 - 206) PAGE 1 Entertainment News, Specialist, Secondary Channels, Movies & Sports & Music International & Adult & Radio & Documentaries Religion, Kids & Shopping Entertainment & Documentaries 101 RTÉ One HD 201 RTÉ One+1 171 Disc.History 271 Disc.History+1 954 BBC One London (AD) 102 RTÉ Two HD 172 Discovery Shed 969 BBC Two Eng (AD) 103 TV3 HD 203 TV3+1 173 BET:BlackEntTv 976 BBC One HD (AD) 104 TG4 HD 174 VH1 994 Sky Atlantic VIP 105 3e HD 175 BEN 995 Sky Atlantic VIP HD 106 Sky One HD 206 Sky One+1 177 Home & Health 277 HomeHealth+1 996 Chl Line-up 107 Sky Living HD 207 Sky Living+1 178 DMAX 278 DMAX+1 998 Sky Intro 108 Sky Atlantic HD 208 Sky Atlantic+1 179 True Ent 279 True Ent+1 999 Channel 999 109 W HD 209 W+1 180 truTV 280 truTV+1 110 GOLD 210 GOLD+1 181 Sony Crime 2 111 Dave HD 211 Dave ja vu 182 GNTV 112 Comedy Central 212 ComedyCent+1 183 VICE 113 Universal 213 Universal+1 184 Horse & Country 114 SYFY HD 214 SYFY+1 185 propeller 116 Be3 187 Blaze 121 SkySp Mix HD 188 Disc.Turbo 288 Disc.Turbo+1 122 Sky Arts HD 189 Property Show 123 Sky Two 190 Animal Planet HD 290 Animal Plnt+1 124 FOX HD 224 FOX+1 191 mytv 125 Discovery 225 Discovery+1 192 Showcase 292 Showcase+1 -

Promoting Competition and Investment in Fibre Networks: BT Regulatory Financial Reporting

Promoting competition and investment in fibre networks: BT Regulatory Financial Reporting Reporting requirements covering wholesale fixed telecoms markets 2021-26 CONSULTATION: Publication Date: 6 February 2020 Closing Date for Responses: 1 April 2020 2020 BT Regulatory Financial Reporting Consultation Contents Section 1. Overview 2 2. Introduction 4 3. Regulatory reporting remedies in the Wholesale Fixed Telecoms Market Review 10 4. Published performance schedules 15 5. Preparation and assurance requirements 51 6. Information provided to Ofcom 81 7. Proposed SMP condition, directions and legal tests 92 Annexes A1. Responding to this consultation 104 A2. Ofcom’s consultation principles 107 A3. Consultation coversheet 108 A4. Consultation questions 109 A5. Draft legal instruments 110 1 2020 BT Regulatory Financial Reporting Consultation 1. Overview 1.1 On 8 January 2020, we published the consultation for our Wholesale Fixed Telecoms Market Review (WFTMR)1. This document sets out our proposed regulatory financial reporting requirements on BT in these markets. BT’s regulatory reporting will be subject to these requirements from April 2021 for five years. 1.2 Because the WFTMR covers most wholesale fixed telecoms markets we regulate and will determine our regulatory approach for the next five years, we are taking the opportunity to conduct a more holistic review of BT’s reporting requirements. This will ensure they remain fit for purpose while making the published information more accessible and easier to understand. 1.3 Our proposals cover the preparation and presentation of information published by BT, and information provided privately to Ofcom. What we are proposing We are proposing to impose regulatory financial reporting requirements on BT which require the production of Regulatory Financial Statements (RFS). -

Faster and Cheaper Than BT Unlimited Infinity 1 Based on Wired and Not Wi-Fi Connections

Faster and cheaper than BT Unlimited Infinity 1 Based on wired and not Wi-Fi connections. Sky’s fastest up to 76Mb unlimited Fibre Max is faster and cheaper than BT’s entry level up to 52Mb unlimited Infinity 1. BT’s 76Mb service is more expensive and not faster than Sky Fibre Max. Switch from BT to new Sky Fibre Max £15 a month for 12 months Monthly Sky Line Rental £17.40 applies Below is an illustation of what a BT Unlimited Infinity 1 customer, outside their minimum term, would pay if they switched to Sky Fibre Max BT Sky BT Infinity 1 Unlimited Sky Fibre Max Advertised headline download speed Up to 52Mb Up to 76Mb Usage Cap Unlimited Unlimited Minimum term N/A 12 mths Monthly price for months 1 - 12 £26.00 £15.00 Monthly standard cost of line rental £18.99 £17.40 Activation fee £0.00 £39.00 Router Delivery charge £0.00 £9.95 TOTAL COST OVER 12 MONTHS £539.88 £437.75 Features: BT Smart Hub Sky Hub BT NetProtect on 2 devices & BT parental controls Sky Broadband Shield 100GB BT Cloud Storage Sky WiFi UK Weekend Calls 12 months free McAfee Internet Trial BT Sport from free Selected Fibre areas only. Speeds vary by location. £9.95 router delivery charge. Upfront payment may be required. Subject to status. Faster & Cheaper: Sky Fibre Max offers faster download speeds than BT Unlimited Infinity 1 (see also Ofcom report March 2016). External factors such as internet congestion and home wiring can affect speed. -

Virgin Media Submission

NON-CONFIDENTIAL VERSION VIRGIN MEDIA LIMITED OFCOM INVESTIGATION INTO THE UK PAY TV INDUSTRY1 SUPPLEMENTARY SUBMISSION OF 15 AUGUST 2008 1. INTRODUCTION: UK PAY TV CONSUMERS CAN BE BETTER SERVED 1.1 In January 2007, Virgin Media Limited ("Virgin Media"), together with British Telecommunications plc, Setanta Sport Holdings Limited and Top Up TV Europe Limited (together, "the Parties"), jointly made a submission to Ofcom demonstrating that competition in the UK pay TV market is not working effectively, and calling for Ofcom to make a market investigation reference to the Competition Commission. In this initial submission, a number of subsequent submissions and responses to numerous information request responses2, Virgin Media has provided voluminous evidence of market failure and highlighted specific areas of consumer detriment which result from this market failure. 1.2 Consumers would be demonstrably better off if steps were taken to remedy the features of the market which are preventing, restricting or distorting competition in the supply of pay TV in the UK. Against that background, this supplementary submission provides: (a) further evidence that consumers are not being well served by the current market structure; and (b) [CONFIDENTIAL], a more detailed explanation of the ways that Virgin Media could innovate (and the types of offerings consumers could expect to see) were the distorting features of the market corrected. 1.3 Ofcom has a discretion under section 131 of the Enterprise Act ("EA") to make a market investigation reference to the Competition Commission where: "… it has reasonable grounds to suspect that any feature, or combination of features, of a market in the United Kingdom for goods and services prevents, restricts or distorts competition in connection with the supply or acquisition of any goods or services in the United Kingdom or a part of the United Kingdom." 1.4 There can be no question such "reasonable grounds" have been established since the inception of this process approximately nineteen months ago. -

Determination of Merger Notification M/14/018

DETERMINATION OF MERGER NOTIFICATION M/14/018 - Sony / Step Topco (CSC Media) Section 21 of the Competition Act 2002 Proposed acquisition by Sony Corporate Services Europe Limited of Step Topco Limited, the holding company of CSC Media Group Limited Dated 28 July 2014 Introduction 1. On 1 July 2014, in accordance with section 18(1)(b) of the Competition Act 2002 (“the Act”), the Competition Authority (“the Authority”) received notification of a proposed transaction whereby Sony Corporate Services Europe Limited (“Sony Europe”) would acquire Step Topco Limited, the holding company of CSC Media Group Limited (together “CSC Media”). 2. On 2 July 2014, pursuant to section 23(1) of the Act, the Authority forwarded a copy of the notification to the Minister for Jobs, Enterprise and Innovation and published notice of the notification on its website, indicating that the proposed transaction was a “media merger”. The Undertakings Involved The Acquirer 3. Sony Corporation is the parent of the Sony group of companies, headquartered in Tokyo, Japan and operates in several segments worldwide, including electronics, electronic games and game consoles, entertainment services and financial services. 4. Sony Europe, incorporated in the United Kingdom, is a wholly-owned and controlled indirect subsidiary of Sony Corporation 1 which currently has eight (8) television channels available on the island of Ireland (with an additional four channels on a one hour time-delay / time- shift): i. Sony Entertainment Television (Sony Entertainment Television +1) ii. More>Movies (More>Movies +1) iii. Sony Movie Channel (Sony Movie Channel +1) iv. Movies4Men (Movies4Men +1) v. Sony Entertainment Television Asia vi. -

Statement: Ofcom's Plan of Work 2021/22

Ofcom’s plan of work 2021/22 Making communications work for everyone Ofcom’s plan of work 2021/22 – Welsh translation STATEMENT: Publication Date: 26 March 2021 Contents Section 1. Chief Executive’s foreword 1 2. Overview 3 3. Our goals and priorities for 2021/22 9 4. Delivering good outcomes for consumers across the UK 31 Annex A1. What we do 37 A2. Project work for 2021/2022 39 Plan of Work 2021/22 1. Chief Executive’s foreword Ofcom is the UK’s communications regulator, with a mission to make communications work for everyone. We serve the interests of consumers and businesses across the UK’s nations and regions, through our work in mobile and fixed telecoms, broadcasting, spectrum, post and online services. Over the past year we have learned that being connected is everything. High-quality, reliable communications services have never mattered more to people’s lives. But as consumers shift their habits increasingly online, our communications sectors are transforming fast. It is an exciting moment for our industries and for Ofcom as a regulator - it requires long-term focus alongside speed and agility in response to change. Against this backdrop our statement sets out our detailed goals for the coming financial year, and how we plan to achieve them. On telecoms, Ofcom has just confirmed a new long-term framework for investment in gigabit- capable fixed networks. In the coming year, we will shift our focus to support delivery against this programme, alongside investment and innovation in 5G and new mobile infrastructure. Following legislation in Parliament, we will put in place new rules to hold operators to account for the security and resilience of their networks. -

Sky Broadband Shield Guide Parental Controls

Parental controls guide Sky Broadband Shield guide Parental Controls information Type of guide Broadband & mobile networks Features and Benefits Sky Broadband Shield is a set of tools designed by Sky to help make the internet a safer place for your whole family and offers the following features – malware protection and parental controls. What specific content can I restrict? Phishing & Malware Drugs & Criminal Skills File Sharing & Hacking Inappropriate content Online games Pornography & Adult Infected Sites Weapons & Violence, Gore Privacy and identity theft Social networking & Hate What do I need? A Sky ID (Username and Password) - If you haven’t signed up, you will need a contact email address and your Sky account number or your account direct debit details. Sky Broadband Shield guide Step by step guide 1 Go to Sky.com, log into your account using your Sky ID (username) and password Sky Broadband Shield guide Step by step guide 2 Get to your Broadband Shield settings by going to My Account. Next, click the Broadband & Talk option. Scroll down and click on the Broadband Shield option. Here you will see the settings to apply for each Custom, PG, 13, Adults and you can also Disable Shield. 1 2 3 Sky Broadband Shield guide 4 Sky Broadband Shield guide Step by step guide 3 Choose when Sky Broadband Shield should be active Scroll down until you reach this section then choose whether you want the Shield to be ‘Always active’ or you can choose to set it at certain times of the day. Please note, when the Broadband shield is inactive, you’ll see sites suitable for adults but will still be protected from phishing and malware sites. -

Tv Uk Freesat

Tv uk freesat loading Skip to content Freesat Logo TV Guide Menu. What is Freesat · Channels · Get Freesat · THE APP · WHAT'S ON · Help. Login / Register. My Freesat ID. With over channels - and 13 in high definition - it's not hard to find unbelievably good TV. With Freesat's smart TV Recorders you can watch BBC iPlayer, ITV Hub*, All 4, Demand 5 and YouTube on your TV. Tune into our stellar line-up of digital radio channels and get up to date Get Freesat · What's on · Sport. If you're getting a new TV, choose one with Freesat built in and you can connect directly to your satellite dish with no need for a separate box. You can now even. With a Freesat Smart TV Recorder you can enjoy the UK's favourite Catch Up services: BBC iPlayer, ITV Hub*, All 4 & Demand 5, plus videos on YouTube. Freesat TV Listings. What's on TV now and next. Full grid view can be viewed at Freesat is a free-to-air digital satellite television joint venture between the BBC and ITV plc, . 4oD launched on Freesat's Freetime receivers on 27 June , making Freesat the first UK TV platform to host the HTML5 version of 4oD. Demand Owner: BBC and ITV plc. Freesat, the satellite TV service from the BBC and ITV, offers hundreds of TV and radio channels to watch Lifestyle: Food Network UK, Showcase TV, FilmOn. FREESAT CHANNEL LIST - TV. The UK IPTV receiver now works on both wired internet and WiFi which , BET Black Entertainment TV, Entertainment. -

British Sky Broadcasting Group Plc Annual Report 2009 U07039 1010 P1-2:BSKYB 7/8/09 22:08 Page 1 Bleed: 2.647 Mm Scale: 100%

British Sky Broadcasting Group plc Annual Report 2009 U07039 1010 p1-2:BSKYB 7/8/09 22:08 Page 1 Bleed: 2.647mm Scale: 100% Table of contents Chairman’s statement 3 Directors’ report – review of the business Chief Executive Officer’s statement 4 Our performance 6 The business, its objectives and its strategy 8 Corporate responsibility 23 People 25 Principal risks and uncertainties 27 Government regulation 30 Directors’ report – financial review Introduction 39 Financial and operating review 40 Property 49 Directors’ report – governance Board of Directors and senior management 50 Corporate governance report 52 Report on Directors’ remuneration 58 Other governance and statutory disclosures 67 Consolidated financial statements Statement of Directors’ responsibility 69 Auditors’ report 70 Consolidated financial statements 71 Group financial record 119 Shareholder information 121 Glossary of terms 130 Form 20-F cross reference guide 132 This constitutes the Annual Report of British Sky Broadcasting Group plc (the ‘‘Company’’) in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards (‘‘IFRS’’) and with those parts of the Companies Act 2006 applicable to companies reporting under IFRS and is dated 29 July 2009. This document also contains information set out within the Company’s Annual Report to be filed on Form 20-F in accordance with the requirements of the United States (“US”) Securities and Exchange Commission (the “SEC”). However, this information may be updated or supplemented at the time of filing of that document with the SEC or later amended if necessary. This Annual Report makes references to various Company websites. The information on our websites shall not be deemed to be part of, or incorporated by reference into, this Annual Report. -

Liste Des Chaines

Available channel temporary unabled channel disabled channel Channels List channel replay Setanta Sport 46 92 Gold Family UK Asian UK 47 Box Nation channel number channel name 93 Dave channel number channel name channel number channel name 48 ESPN HD 1 beIN Sports News HD 94 Alibi 104 SKY ONE 158 Zee tv UK 49 Eurosport UK 95 E4 105 Sky Two UK 159 Zee cinema UK 2 Bein Sports Global HD 50 Eurosport 2 UK 96 More 4 106 Sky Living 160 Zee Punjabi UK 3 BEIN SPORT 1 HD 51 Sky Sports News 97 Dmax 107 Sky Atlantic UK 161 Zing UK 52 At The Races 4 BEIN SPORT 2 HD 98 5 STAR 108 Sky Arts1 162 Star Gold UK 53 Racing UK 5 BEIN SPORT 3 HD 99 3E 109 Sky Real Lives UK 163 Star Jalsha UK 54 Motor TV 100 Magic 110 Fox UK 164 Star Plus UK 6 BEIN SPORT 4 HD 55 Manchester United Tv 101 TV 3 111 Comedy Central UK 165 Star live UK 7 BEIN SPORT 5 HD 56 Chealsea Tv 102 Film 4 121 Comedy Central Extra UK 166 Ary Digital UK 57 Liverpool Tv 8 BEIN SPORT 6 HD 103 Flava 125 Nat Geo UK 167 Sony Tv UK 113 Food Network 126 Nat Geo Wild uk 168 Sony Sab Tv UK 9 BEIN SPORT 7 HD Cinema Uk 114 The Vault 127 Discovery UK 169 Aaj Tak UK 10 BEIN SPORT 8 HD channel number channel name 115 CBS Reality 128 Discovery Science uk 170 Geo TV UK 60 Sky Movies Premiere UK 11 BEIN SPORT 9 HD 116 CBS Action 129 Discovery Turbo UK 171 Geo news UK 61 Sky Select UK 12 BEIN SPORT 10 HD 130 Discovery History 172 ABP news Uk 62 Sky Action UK 117 CBS Drama 131 Discovery home UK 13 BEIN SPORT 11 HD 63 Sky Modern Great UK 118 True Movies 132 Investigation Discovery 64 Sky Family UK 119 True Movies -

Annex 2: Providers Required to Respond (Red Indicates Those Who Did Not Respond Within the Required Timeframe)

Video on demand access services report 2016 Annex 2: Providers required to respond (red indicates those who did not respond within the required timeframe) Provider Service(s) AETN UK A&E Networks UK Channel 4 Television Corp All4 Amazon Instant Video Amazon Instant Video AMC Networks Programme AMC Channel Services Ltd AMC Networks International AMC/MGM/Extreme Sports Channels Broadcasting Ltd AXN Northern Europe Ltd ANIMAX (Germany) Arsenal Broadband Ltd Arsenal Player Tinizine Ltd Azoomee Barcroft TV (Barcroft Media) Barcroft TV Bay TV Liverpool Ltd Bay TV Liverpool BBC Worldwide Ltd BBC Worldwide British Film Institute BFI Player Blinkbox Entertainment Ltd BlinkBox British Sign Language Broadcasting BSL Zone Player Trust BT PLC BT TV (BT Vision, BT Sport) Cambridge TV Productions Ltd Cambridge TV Turner Broadcasting System Cartoon Network, Boomerang, Cartoonito, CNN, Europe Ltd Adult Swim, TNT, Boing, TCM Cinema CBS AMC Networks EMEA CBS Reality, CBS Drama, CBS Action, Channels Partnership CBS Europe CBS AMC Networks UK CBS Reality, CBS Drama, CBS Action, Channels Partnership Horror Channel Estuary TV CIC Ltd Channel 7 Chelsea Football Club Chelsea TV Online LocalBuzz Media Networks chizwickbuzz.net Chrominance Television Chrominance Television Cirkus Ltd Cirkus Classical TV Ltd Classical TV Paramount UK Partnership Comedy Central Community Channel Community Channel Curzon Cinemas Ltd Curzon Home Cinema Channel 5 Broadcasting Ltd Demand5 Digitaltheatre.com Ltd www.digitaltheatre.com Discovery Corporate Services Discovery Services Play -

Made on Merseyside

Made on Merseyside Feature Films: 2010’s: Across the Universe (2006) Little Joe (2019) Beyond Friendship Ip Man 4 (2018) Yesterday (2018) (2005) Tolkien (2017) X (2005) Triple Word Score (2017) Dead Man’s Cards Pulang (2016) (2005) Fated (2004) Film Stars Don’t Die in Liverpool (2016) Alfie (2003) Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them Digital (2003) (2015) Millions (2003) Florence Foster Jenkins (2015) The Virgin of Liverpool Genius (2014) (2002) The Boy with a Thorn in His Side (2014) Shooters (2001) Big Society the Musical (2014) Boomtown (2001) 71 (2013) Revenger’s Tragedy Christina Noble (2013) (2001) Fast and Furious 6 John Lennon-In His Life (2012) (2000) Jack Ryan: Shadow Recruit Parole Officer (2000) (2012) The 51st State (2000) Blood (2012) My Kingdom Kelly and Victor (2011) (2000) Captain America: The First Avenger Al’s Lads (2010) (2000) Liam (2000) 2000’s: Route Irish (2009) Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows (2009) Nowhere Fast (2009) Powder (2009) Nowhere Boy (2009) Sherlock Holmes (2008) Salvage (2008) Kicks (2008) Of Time in the City (2008) Act of Grace (2008) Charlie Noads RIP (2007) The Pool (2007) Three and Out (2007) Awaydays (2007) Mr. Bhatti on Holiday (2007) Outlaws (2007) Grow Your Own (2006) Under the Mud (2006) Sparkle (2006) Appuntamento a Liverpool (1987) No Surrender (1986) Letter to Brezhnev (1985) Dreamchild (1985) Yentl (1983) Champion (1983) Chariots of Fire (1981) 1990’s: 1970’s: Goin’ Off Big Time (1999) Yank (1979) Dockers (1999) Gumshoe (1971) Heart (1998) Life for a Life (1998) 1960’s: Everyone