Dean Winchester: an Existentialist Hero? Dean Winchester: ¿Un Héroe Existencialista?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Truth About Angels

PROJECT CONNECT PROJECT CONNECT PROJECT CONNECT The Truth About Angels by Donald L. Deffner I grew up during the Great Depression in the early 1930s. My father was a minister. Behind our small home was a dirt alley which led nine blocks to downtown Wichita, Kansas. I can remember when I was a boy the hungry, destitute men who came to the back door begging for food. My mother never turned them down. She shared what little we had, even if only a couple of pieces of bread and a glass of milk. My mother didn’t just say, “Depart in peace! I’ll pray for you! Keep warm and well fed!” (See James 2:16.) No. She acted. She gave. Often I was curious about these mysterious and somewhat scary men. I had a sense that they were “different” than I was, not worse, not better, just different. I always watched these strangers heading back up the alley toward downtown, and sometimes, in a cops-and-robbers fashion, I secretly followed them, jumping behind bushes so I wouldn’t be seen. I think I half expected them to suddenly disappear. After all, my Sunday school teacher, encouraging us to be kind and care for strangers, told us the Bible says that, by doing so, many people have entertained angels without knowing it (see Hebrews 13:2). I never saw any of the men disappear. They were ordinary, hungry human beings. But my Sunday school teacher was right. God does send His angels to us, and they do interact with us—not just to test us and see if we are kind, but to protect us and guide us. -

Below the Belt: Situational Ethics for Uniethical Situations

The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare Volume 7 Issue 4 July Article 2 July 1980 Below the Belt: Situational Ethics for Uniethical Situations Gale Goldberg University of Louisville Joy Elliott University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/jssw Part of the Ethics and Political Philosophy Commons, and the Social Work Commons Recommended Citation Goldberg, Gale and Elliott, Joy (1980) "Below the Belt: Situational Ethics for Uniethical Situations," The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare: Vol. 7 : Iss. 4 , Article 2. Available at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/jssw/vol7/iss4/2 This Article is brought to you by the Western Michigan University School of Social Work. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BELOW THE BELT: SITUATIONAL ETHICS FOR UNIETHICAL SITUATIONS Gale Goldberg, Ed.D. Jqy Elliott, M.S.S.Uj. Associate Professor Assistant Professor Kent School of Social Work Kent School of Social Work University of Louisville University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky 40208 Louisville, Kentucky 40208 The word "politics" generally conjures up images of smoke- filled, back rooms where unscrupulous men in shirt sleeves chew their cigars and make shady deals that serve partisan interests. But politics is neither inherently shady nor specific to back rooms. In fact, as long as society is differentiated along ethnic, sex and social class lines, politics pervades all of social life. You are involved in politics and so is your mother. A statement or decision is political when either the content of the issue is viewed differently by. people from different social groups, e.g. race, sex, age, or the decision has different con- sequences for different social groups, or both. -

Indigo in Motion …A Decidedly Unique Fusion of Jazz and Ballet

A Teacher's Handbook for Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre's Production of Indigo in Motion …a decidedly unique fusion of jazz and ballet Choreography Kevin O'Day Lynne Taylor-Corbett Dwight Rhoden Music Ray Brown Stanley Turrentine Lena Horne Billy Strayhorn Sponsored by Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre's Arts Education programs are supported by major grants from the following: Allegheny Regional Asset District Claude Worthington Benedum Foundation Pennsylvania Council on the Arts The Hearst Foundation Sponsoring the William Randolph Hearst Endowed Fund for Arts Education Additional support is provided by: Alcoa Foundation, Allegheny County, Bayer Foundation, H. M. Bitner Charitable Trust, Columbia Gas of Pennsylvania, Dominion, Duquesne Light Company, Frick Fund of the Buhl Foundation, Grable Foundation, Highmark Blue Cross Blue Shield, The Mary Hillman Jennings Foundation, Milton G. Hulme Charitable Foundation, The Roy A. Hunt Foundation, Earl Knudsen Charitable Foundation, Lazarus Fund of the Federated Foundation, Matthews Educational and Charitable Foundation,, McFeely-Rogers Fund of The Pittsburgh Foundation, William V. and Catherine A. McKinney Charitable Foundation, Howard and Nell E. Miller Foundation, The Charles M. Morris Charitable Trust, Pennsylvania Department of Community and Economic Development, The Rockwell Foundation, James M. and Lucy K. Schoonmaker Foundation, Target Corporation, Robert and Mary Weisbrod Foundation, and the Hilda M. Willis Foundation. INTRODUCTION Dear Educator, In the social atmosphere of our country, in this generation, a professional ballet company with dedicated and highly trained artists cannot afford to be just a vehicle for public entertainment. We have a mission, a commission, and an obligation to be the standard bearer for this beautiful classical art so that generations to come can view, enjoy, and appreciate the significance that culture has in our lives. -

Will This Manhattan Projects Original Artwork Cliffhanger Make Another

COMICS COSPLAY TV/FILM GAMES SUBMIT CGC Search … Will This Manhattan Projects Original Artwork Cliffhanger Make Another Big Splash? Posted by Mark Seifert March 19, 2014 0 Comments Facebook Twitter Pinterest LinkedIn Tumblr Email Reddit [The Manhattan Projects #18 has been out for a couple weeks, but still — if you haven’t read this issue and plan to, you might want to skip this post for now.] Several years into the digital era for both comics reading and comics production, I still love to look at original comic art up close. The look and feel of the art board, the subtle texture of the ink, the faint traces of changes and corrections… it all adds up to a little extra insight into the time and circumstances behind the comics book’s creation. We’ve mentioned a bunch of noteworthy original art sales here in recent times — from that awe-inspiring Golden Age Action Comics #15 cover by Fred Guardineer, to this Silver Age Fantastic Four #55 page by Jack Kirby, to this Bronze Age classic Amazing Spider- Man #121 cover by John Romita Sr, down to the current record holder for a piece of American comic book art with this Amazing Spider-Man #328 cover by Todd McFarlane. And increasingly, original art sales from much more recent comics are turning heads as well. It’s probably no surprise that Skottie Young original art is highly sought after, or that Walking Dead original art — even panel pages — can command some eye- popping prices. But modern comic art collectors have broadened their interests to many other artists and titles of quality in recent times, such as this Pia Guerra Y: The Last Man panel page that recently went for $1000. -

Episode 47 – “A Very Merry Supernatural Christmas”

Episode 47 – “A Very Merry Supernatural Christmas” Release Date: December 24, 2018 Running Time: 1 hour, 11 minutes Sally: Kay. Fuck, marry, kill. Sam, Dean, Cas. Emily: Ah, fu-- (laugh) Brie: I feel like that’s easy. (laugh) Emily: That’s super easy. Sally: I just -- we gotta start the episode somehow. Emily: OK, kill Sam, obviously. Brie: Duh. Yeah, no, duh. Yeah. Emily: Yeah. Brie: Yeah. Mm. Sally: (laugh) Emily: Uh, then I guess I’d marry Cas? Brie: Yeah … Sally: Fuck Dean? Emily: Yeah. Sally: That’s where I was sitting too. Brie: Yeah. Sally: So we’re all in agreement. Brie: Yeah. Emily: I just -- Cas actually has a personality I can stand. When he actually develops a personality, which is later, I guess, in the series. Sally: Yeah. Brie: I do think, though, that, like, the emotional parts of Dean -- Emily: Yeah. Brie: If that -- if that was, like, turned on all the time. Marry. Emily: My idealized version of Dean -- Brie: Yeah. Emily: I would marry. Brie: Yeah. Yeah. Emily: But the Dean that’s actually on the show? Mm-mm. Fuckin’ leave. Sally: OK! (all laugh) Emily, singing: Have a holly, jolly Christmas … Sally: Um, earlier I was reading an article called -- Brie: Oh! Oh, yeah. Yeah. Emily: Don’t repeat it. It’s the worst. Sally: (laughing) Emily: I know we’re an explicit podcast, but this might be the line of what’s too explicit. Brie: (laugh) Sally: K, it was an article about monster erotica, and the title of the article is also a title for the book. -

ABSTRACT the Women of Supernatural: More Than

ABSTRACT The Women of Supernatural: More than Stereotypes Miranda B. Leddy, M.A. Mentor: Mia Moody-Ramirez, Ph.D. This critical discourse analysis of the American horror television show, Supernatural, uses a gender perspective to assess the stereotypes and female characters in the popular series. As part of this study 34 episodes of Supernatural and 19 female characters were analyzed. Findings indicate that while the target audience for Supernatural is women, the show tends to portray them in traditional, feminine, and horror genre stereotypes. The purpose of this thesis is twofold: 1) to provide a description of the types of female characters prevalent in the early seasons of Supernatural including mother-figures, victims, and monsters, and 2) to describe the changes that take place in the later seasons when the female characters no longer fit into feminine or horror stereotypes. Findings indicate that female characters of Supernatural have evolved throughout the seasons of the show and are more than just background characters in need of rescue. These findings are important because they illustrate that representations of women in television are not always based on stereotypes, and that the horror genre is evolving and beginning to depict strong female characters that are brave, intellectual leaders instead of victims being rescued by men. The female audience will be exposed to a more accurate portrayal of women to which they can relate and be inspired. Copyright © 2014 by Miranda B. Leddy All rights reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS Tables -

The Relevance of Joseph Fletcher's Situation Ethics for Animal Experimentation in Clinical Studies

and M cal e ni d li ic C a Monday, J Clin Med Sci 2018, 2:2 l f S o c Journal of Clinical and Medical l i e a n n r c u e o s J Sciences Review Article Open Access The Relevance of Joseph Fletcher's Situation Ethics for Animal Experimentation in Clinical Studies Osebor Ikechukwu Monday* Department of General Studies (Arts and Humanities), Delta State Polytechnic Ogwashi-Uku, Ogwashi-Uku, Nigeria Received: July 25, 2018; Accepted: August 27, 2018; Published: August 31, 2018 *Corresponding author: Monday OI, Department of General Studies (Arts and Humanities), Delta State Polytechnic Ogwashi-Uku, Ogwashi-Uku, Nigeria, Tel: +2348037911701; E-mail: [email protected] Copyright: © 2018 Monday OI. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the creative commons attribution license, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract The need for continual progress in medical research is one among the challenges today facing humankind. On- going, necessary medical research involving animal subjects will be defended from a Utilitarian standpoint. Animal experimentation can be conducted in such a way that injury and suffering to the animal subjects can be minimized. Clinical studies have been necessary for the eradication of many diseases, such as smallpox and polio and promise similar results for other medical conditions in the future. The ethical and emotional demands placed upon the experimenter during clinical trials, as well as the suffering of the animal subjects, presents us with an ethical dilemma concerning the moral justification of animal experimentation for clinical studies. -

A University of Wisconsin Arboretum Narrative: Changing Landscapes and Changing Meaning

A University of Wisconsin Arboretum Narrative: Changing Landscapes and Changing Meaning Molly Evjen, Andreas Karlsson, Ryan Kelly, Matt Lamb Geography 565 Fall 2010 Abstract As societies change, so too does their relationship with the land. These changing relationships are reflected in and imprinted upon the land on which they live. In order to demonstrate how the landscape of the UW Arboretum has mirrored this changing association with nature through time, we have conducted an environmental history which focuses on four vignettes representing major changes in this relationship. Through research of primary data sources such as historical newsletters, observation, and plat map analysis our research shows that the Arboretum is a palimpsest of landforms and meaning resulting from these changing relationships. Introduction Environmental History is the study of the changing relationship between human beings and the natural world. We believe that the UW arboretum is a landscape that, through time, has been reflective of this changing relationship. Our purpose is to demonstrate how the landscape of the UW Arboretum has changed through time and how these changes reflect a cycle of changing, complex relationships between society and nature. We utilize multiple primary resources in our analysis such as plat maps, CCC newsletters, photographs, observations and personal reflections from our own field journals. We will demonstrate how the UW Arboretum is representative of this changing relationship in a number of ways. It is a reminder of early connections to the land represented by numerous burial mounds. The mounds also symbolize, through the multitude of possible interpretations of their purpose, people’s ever-changing interpretations of our relationship with nature in general. -

Cultural Spectacle: Double Dragon Dance

Cultural Spectacle An unparalleled series of visual spectacles will introduce Richmond, BC, Canada to the world during the Vancouver 2010 Olympic Winter Games. Each spectacle will tell the story of Richmond’s local economy, people, heritage and natural environment. Asia’s legendary supernatural creature visits Richmond for Chinese New Year: The long and short of it A spectacular double-dragon dance featuring 150 metre and 75 metre dragons will visit Richmond, BC on Chinese New Year 2010. • The dragon is a symbol of luck in the Chinese • The dragons are 150 metres (492 feet) and 75 culture. metres (246 feet) long. They are predominantly green in colour which symbolizes a great harvest, • Legends have it that the City of Richmond is a or in modern times, abundance. precious pearl in the mouth of the Fraser River and this attracts the dragon. This is why Richmond is • A double dragon dance, rarely seen in Western known as a lucky city to live in. exhibitions, involves two troupes of dancers intertwining the dragons. • A spectacular double dragon dance with two impressively long dragons will visit Richmond and • Part of the dragon myth is the longer the creature, Richmond’s O Zone celebration site on Chinese the more luck it will bring. New Year (Feb. 14, 2010). The Richmond O Zone • Dragons (known as “long” in Chinese) are believed is an official celebration site of the 2010 Olympic to bring good luck to people, which is reflected in Winter Games and runs from February 12 to the their qualities including great power, dignity, 28, 2010. -

The Challenge of Ethics

The Challenge of Ethics A Center for Continuing Education 1465 Northside Drive, Suite 213 Atlanta, Georgia 30318 (404) 355-1921 – (800) 344-1921 Fax: (404) 355-1292 THE CHALLENGE OF ETHICS TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1 -- The Foundation of Ethics 1 Defining Ethics 1 The History of Ethics 1 Greek Ethics 2 Roman Ethics 3 Christian-Based Ethics 3 Truth 3 Modern Day Ethics 5 The Interpretation of Ethics 5 The Philosophies of Ethics 5 Deontological Ethics 6 Virtue Ethics 7 Normative Ethics 8 Analytic Ethics (Metaethics) 8 Situational Ethics 9 Descriptive Ethics 10 Consequentialist Ethics 10 Dominant Ethical Philosophies 11 Ethical Relativism 11 The Duty of Ethics 13 The Duty of Social Virtue 14 The Duty of Responsibility 14 The Behavior of Ethics 15 Summary 16 Chapter 2 -- The Development of Personal Ethics 17 Personal Ethics 17 Developing Personal Ethics 17 Influence From Family 18 Influence of Culture 18 Influence of Religious Beliefs 19 Influence of Habits 19 Principles of Personal Ethics 20 Creating a Personal Code of Ethics 21 Chapter Three -- Business Ethics 23 Understanding Professional Ethics 23 The Importance of Ethics in Professionalism 24 Approaches To Ethical Standards 25 Common Good Approach 25 Fairness or Justice Approach 26 Moral Rights Approach 26 Utilitarian Approach 26 Universalism Approach 27 Virtue Approach 28 Steps in Ethical Decision Making 28 Identifying the Situation 28 Determine Who’ll be Affected by The Decision 28 Assess Relevant Aspects Of The Situation 29 Relevant Formal Ethical Standards Review 29 Review Relevant -

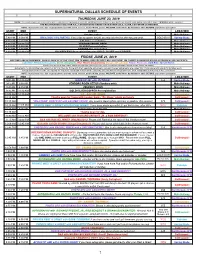

Supernatural Dallas Schedule of Events

SUPERNATURAL DALLAS SCHEDULE OF EVENTS THURSDAY, JUNE 20, 2019 NOTE: Pre-registration is not a necessity, just a convenience! Get your credentials, wristband and schedule so you don't have to wait again during convention days. VENDORS will be open too! PRE-REGISTRATION IS ONLY FOR FULL CONVENTION ATTENDEES WITH EITHER GOLD, SILVER, COPPER OR GA WEEKEND. NOTE: If you have solo, duo or group photo ops with Jared, Jensen, and/or Misha, please VALIDATE at the Photo Op Validation table BEFORE your photo op begins! START END EVENT LOCATION 3:30 PM 7:45 PM Vendors set-up Main Hallway 7:00 PM 9:30 PM BRI & DICK 'S PJ PARTY!!! If you’d like to register tonight, you may join the line after the party ends. SOLD OUT! Spring Glade 7:45 PM 8:30 PM GOLD Pre-registration Main Hallway 7:45 PM 10:00 PM VENDORS ROOM OPEN Main Hallway 8:30 PM 9:00 PM SILVER Pre-registration Main Hallway 9:00 PM 9:30 PM COPPER Pre-registration Main Hallway 9:30 PM 10:00 PM GA WEEKEND Pre-registration plus GOLD, SILVER and COPPER Main Hallway FRIDAY, JUNE 21, 2019 *END TIMES ARE APPROXIMATE. PLEASE SHOW UP AT THE START TIME TO MAKE SURE YOU DON’T MISS ANYTHING! WE CANNOT GUARANTEE MISSED AUTOGRAPHS OR PHOTO OPS. Light Blue: Private meet & greets, Green: Autographs, Red: Theatre programming, Orange: VIP schedule, Purple: Photo ops, Dark Blue: Special Events Photo ops are on a first come, first served basis (unless you're a VIP or unless otherwise noted in the Photo op listing) Autographs for Gold/Silver are called row by row, then by those with their separate autographs, pre-purchased autographs are called first. -

Constructing Community and Cosmos: a Bioarchaeological Analysis of Wisconsin Effigy Mound Mortuary Practices and Mound Construction

CONSTRUCTING COMMUNITY AND COSMOS: A BIOARCHAEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF WISCONSIN EFFIGY MOUND MORTUARY PRACTICES AND MOUND CONSTRUCTION By Wendy Lee Lackey-Cornelison A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILSOPHY Anthropology 2012 ABSTRACT CONSTRUCTING COMMUNITY AND COSMOS: A BIOARCHAEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF WISCONSIN EFFIGY MOUND MORTUARY PRACTICES AND MOUND CONSTRUCTION By Wendy Lee Lackey-Cornelison This dissertation presents an analysis of the mounds, human skeletal remains, grave goods, and ritual paraphernalia interred within mounds traditionally categorized as belonging to the Wisconsin Effigy Mound Tradition. The term ‘Effigy Mound Tradition’ commonly refers to a widespread mound building and ritual phenomenon that spanned the Upper Midwest during the Late Woodland (A.D. 600-A.D. 1150). Specifically, this study explores how features of mound construction and burial may have operated in the social structure of communities participating in this panregional ceremonial movement. The study uses previously excavated skeletal material, published archaeological reports, unpublished field notes, and photographs housed at the Milwaukee Public Museum to examine the social connotations of various mound forms and mortuary ritual among Wisconsin Effigy Mound communities. The archaeological and skeletal datasets consisted of data collected from seven mound sites with an aggregate sample of 197 mounds and a minimum number of individuals of 329. The mortuary analysis in this study explores whether the patterning of human remains interred within mounds were part of a system involved with the 1) creation of collective/ corporate identity, 2) denoting individual distinction and/or social inequality, or 3) a combination of both processes occurring simultaneously within Effigy Mound communities.