1 Retaining a New Format: Jazz-Rap, Cultural Memory, and the New

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reviews & Previews

Reviews & Previews ARTISTS & MUSIC S P O T L I G H T SPOTLIGHT SPOTLIGHT SPOTLIGHT SARA LEE THE OFFSPRING Make It Beautiful Conspiracy Of One PRODUCERS: Peter Scherer, Harvey Jones PRODUCER: Brendan O'Brien Righteous Babe RBRO21 Columbia CK 61419 British bassist Sara Lee has been ply- On the winning follow -up to its 1995 ing her feisty musical wares since the smash "Americana," the Offspring late '70s. As an in- demand session play- doesn't stray far from the brand of er, Lee has toured and recorded with adrenaline- fueled punk/pop it first numerous high -profile acts, including helped popularize with Green Day Fiona Apple, the B -52's, Indigo Girls, back in the mid -'90s. But "Conspiracy Thompson Twins, Gang Of Four, and Of One" proves the SoCal rock act to Ryuichi Sakamoto. Four years ago, she still be among the top practitioners of accompanied singer/songwriter Ani the genre, which has most recently AI J LA DiFranco on tours of Europe and been owned by another group of 1 North America. With "Make It Beauti- smart-ass punk revivalists, Blink -182. EDITED BY MICHAEL PAOLETTA ful," the ultra- photogenic Lee finally The band roars out of the gates on the PRU delivers her greatly anticipated solo MUSIO SOULCHILD aptly titled track "Come Out Swing- Pru debut. Throughout the set's 10 tracks, Aijuswannasing ing" and blisters through the first 10 PRODUCERS: various funky beats seamlessly collide with PRODUCERS: various songs without looking back. But as P P Capitol 7243 5 23120 0 9 Def Soul/Def Jam 8289 O decidedly pop mannerisms, and new- opposed to Blink, which powers Webster's defines the word "prudent" With a moniker like Musiq Soulchild, * SHAWN LEE as "capable of exercising sound judg- expectations are high for this soul - Monkey Boy ment." Capitol artist Pru (nee Ren- ster's debut. -

Music Video As Black Art

IN FOCUS: Modes of Black Liquidity: Music Video as Black Art The Unruly Archives of Black Music Videos by ALESSANDRA RAENGO and LAUREN MCLEOD CRAMER, editors idway through Kahlil Joseph’s short fi lm Music Is My Mis- tress (2017), the cellist and singer Kelsey Lu turns to Ishmael Butler, a rapper and member of the hip-hop duo Shabazz Palaces, to ask a question. The dialogue is inaudible, but an intertitle appears on screen: “HER: Who is your favorite fi lm- Mmaker?” “HIM: Miles Davis.” This moment of Black audiovisual appreciation anticipates a conversation between Black popular cul- ture scholars Uri McMillan and Mark Anthony Neal that inspires the subtitle for this In Focus dossier: “Music Video as Black Art.”1 McMillan and Neal interpret the complexity of contemporary Black music video production as a “return” to its status as “art”— and specifi cally as Black art—that self-consciously uses visual and sonic citations from various realms of Black expressive culture in- cluding the visual and performing arts, fashion, design, and, obvi- ously, the rich history of Black music and Black music production. McMillan and Neal implicitly refer to an earlier, more recogniz- able moment in Black music video history, the mid-1990s and early 2000s, when Hype Williams defi ned music video aesthetics as one of the single most important innovators of the form. Although it is rarely addressed in the literature on music videos, the glare of the prolifi c fi lmmaker’s infl uence extends beyond his signature lumi- nous visual style; Williams distinguished the Black music video as a creative laboratory for a new generation of artists such as Arthur Jafa, Kahlil Joseph, Bradford Young, and Jenn Nkiru. -

Williams, Hipness, Hybridity, and Neo-Bohemian Hip-Hop

HIPNESS, HYBRIDITY, AND “NEO-BOHEMIAN” HIP-HOP: RETHINKING EXISTENCE IN THE AFRICAN DIASPORA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Maxwell Lewis Williams August 2020 © 2020 Maxwell Lewis Williams HIPNESS, HYBRIDITY, AND “NEO-BOHEMIAN” HIP-HOP: RETHINKING EXISTENCE IN THE AFRICAN DIASPORA Maxwell Lewis Williams Cornell University 2020 This dissertation theorizes a contemporary hip-hop genre that I call “neo-bohemian,” typified by rapper Kendrick Lamar and his collective, Black Hippy. I argue that, by reclaiming the origins of hipness as a set of hybridizing Black cultural responses to the experience of modernity, neo- bohemian rappers imagine and live out liberating ways of being beyond the West’s objectification and dehumanization of Blackness. In turn, I situate neo-bohemian hip-hop within a history of Black musical expression in the United States, Senegal, Mali, and South Africa to locate an “aesthetics of existence” in the African diaspora. By centering this aesthetics as a unifying component of these musical practices, I challenge top-down models of essential diasporic interconnection. Instead, I present diaspora as emerging primarily through comparable responses to experiences of paradigmatic racial violence, through which to imagine radical alternatives to our anti-Black global society. Overall, by rethinking the heuristic value of hipness as a musical and lived Black aesthetic, the project develops an innovative method for connecting the aesthetic and the social in music studies and Black studies, while offering original historical and musicological insights into Black metaphysics and studies of the African diaspora. -

Objectivity, Interdisciplinary Methodology, and Shared Authority

ABSTRACT HISTORY TATE. RACHANICE CANDY PATRICE B.A. EMORY UNIVERSITY, 1987 M.P.A. GEORGIA STATE UNIVERSITY, 1990 M.A. UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN- MILWAUKEE, 1995 “OUR ART ITSELF WAS OUR ACTIVISM”: ATLANTA’S NEIGHBORHOOD ARTS CENTER, 1975-1990 Committee Chair: Richard Allen Morton. Ph.D. Dissertation dated May 2012 This cultural history study examined Atlanta’s Neighborhood Arts Center (NAC), which existed from 1975 to 1990, as an example of black cultural politics in the South. As a Black Arts Movement (BAM) institution, this regional expression has been missing from academic discussions of the period. The study investigated the multidisciplinary programming that was created to fulfill its motto of “Art for People’s Sake.” The five themes developed from the program research included: 1) the NAC represented the juxtaposition between the individual and the community, local and national; 2) the NAC reached out and extended the arts to the masses, rather than just focusing on the black middle class and white supporters; 3) the NAC was distinctive in space and location; 4) the NAC seemed to provide more opportunities for women artists than traditional BAM organizations; and 5) the NAC had a specific mission to elevate the social and political consciousness of black people. In addition to placing the Neighborhood Arts Center among the regional branches of the BAM family tree, using the programmatic findings, this research analyzed three themes found to be present in the black cultural politics of Atlanta which made for the center’s unique grassroots contributions to the movement. The themes centered on a history of politics, racial issues, and class dynamics. -

Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67

Listening in Double Time: Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67 Marc Howard Medwin A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by: David Garcia Allen Anderson Mark Katz Philip Vandermeer Stefan Litwin ©2008 Marc Howard Medwin ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT MARC MEDWIN: Listening in Double Time: Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67 (Under the direction of David F. Garcia). The music of John Coltrane’s last group—his 1965-67 quintet—has been misrepresented, ignored and reviled by critics, scholars and fans, primarily because it is a music built on a fundamental and very audible disunity that renders a new kind of structural unity. Many of those who study Coltrane’s music have thus far attempted to approach all elements in his last works comparatively, using harmonic and melodic models as is customary regarding more conventional jazz structures. This approach is incomplete and misleading, given the music’s conceptual underpinnings. The present study is meant to provide an analytical model with which listeners and scholars might come to terms with this music’s more radical elements. I use Coltrane’s own observations concerning his final music, Jonathan Kramer’s temporal perception theory, and Evan Parker’s perspectives on atomism and laminarity in mid 1960s British improvised music to analyze and contextualize the symbiotically related temporal disunity and resultant structural unity that typify Coltrane’s 1965-67 works. -

Vindicating Karma: Jazz and the Black Arts Movement

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2007 Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/ W. S. Tkweme University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Tkweme, W. S., "Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/" (2007). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 924. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/924 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Massachusetts Amherst Library Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/vindicatingkarmaOOtkwe This is an authorized facsimile, made from the microfilm master copy of the original dissertation or master thesis published by UMI. The bibliographic information for this thesis is contained in UMTs Dissertation Abstracts database, the only central source for accessing almost every doctoral dissertation accepted in North America since 1861. Dissertation UMI Services From:Pro£vuest COMPANY 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106-1346 USA 800.521.0600 734.761.4700 web www.il.proquest.com Printed in 2007 by digital xerographic process on acid-free paper V INDICATING KARMA: JAZZ AND THE BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT A Dissertation Presented by W.S. TKWEME Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 W.E.B. -

The 2016 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters

04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS 3/25/16 11:58 AM Page 1 The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN , Chairman DEBORAH F. RUTTER , President CONCERT HALL Monday Evening, April 4, 2016, at 8:00 The Kennedy Center and the National Endowment for the Arts present The 2016 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters GARY BURTON WENDY OXENHORN PHAROAH SANDERS ARCHIE SHEPP Jason Moran is the Kennedy Center’s Artistic Director for Jazz. WPFW 89.3 FM is a media partner of Kennedy Center Jazz. Patrons are requested to turn off cell phones and other electronic devices during performances. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not allowed in this auditorium. 04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS 3/25/16 11:58 AM Page 2 2016 NEA JAZZ MASTERS TRIBUTE CONCERT Hosted by JASON MORAN, pianist and Kennedy Center artistic director for jazz With remarks from JANE CHU, chairman of the NEA DEBORAH F. RUTTER, president of the Kennedy Center THE 2016 NEA JAZZ MASTERS Performances by NEA JAZZ MASTERS: CHICK COREA, piano JIMMY HEATH, saxophone RANDY WESTON, piano SPECIAL GUESTS AMBROSE AKINMUSIRE, trumpeter LAKECIA BENJAMIN, saxophonist BILLY HARPER, saxophonist STEFON HARRIS, vibraphonist JUSTIN KAUFLIN, pianist RUDRESH MAHANTHAPPA, saxophonist PEDRITO MARTINEZ, percussionist JASON MORAN, pianist DAVID MURRAY, saxophonist LINDA OH, bassist KARRIEM RIGGINS, drummer and DJ ROSWELL RUDD, trombonist CATHERINE RUSSELL, vocalist 04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS -

Effets & Gestes En Métropole Toulousaine > Mensuel D

INTRAMUROSEffets & gestes en métropole toulousaine > Mensuel d’information culturelle / n°383 / gratuit / septembre 2013 / www.intratoulouse.com 2 THIERRY SUC & RAPAS /BIENVENUE CHEZ MOI présentent CALOGERO STANISLAS KAREN BRUNON ELSA FOURLON PHILLIPE UMINSKI Éditorial > One more time V D’après une histoire originale de Marie Bastide V © D. R. l est des mystères insondables. Des com- pouvons estimer que quelques marques de portements incompréhensibles. Des gratitude peuvent être justifiées… Au lieu Ichoses pour lesquelles, arrivé à un certain de cela, c’est souvent l’ostracisme qui pré- cap de la vie, l’on aimerait trouver — à dé- domine chez certains des acteurs culturels faut de réponses — des raisons. Des atti- du cru qui se reconnaîtront. tudes à vous faire passer comme étranger en votre pays! Il faut le dire tout de même, Cependant ne généralisons pas, ce en deux décennies d’édition et de prosély- serait tomber dans la victimisation et je laisse tisme culturel, il y a de côté-ci de la Ga- cet art aux politiques de tous poils, plus ha- ronne des décideurs/acteurs qui nous biles que moi dans cet exercice. D’autant toisent quand ils ne nous méprisent pas tout plus que d’autres dans le métier, des atta- simplement : des organisateurs, des musi- ché(e)s de presse des responsables de ciens, des responsables culturels, des théâ- com’… ont bien compris l’utilité et la néces- treux, des associatifs… tout un beau monde sité d’un média tel que le nôtre, justement ni qui n’accorde aucune reconnaissance à inféodé ni soumis, ce qui lui permet une li- photo © Lisa Roze notre entreprise (au demeurant indépen- berté d’écriture et de publicité (dans le réel dante et non subventionnée). -

The JB's These Are the JB's Mp3, Flac

The J.B.'s These Are The J.B.'s mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Funk / Soul Album: These Are The J.B.'s Country: US Released: 2015 Style: Funk MP3 version RAR size: 1439 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1361 mb WMA version RAR size: 1960 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 880 Other Formats: APE VOX AC3 AA ASF MIDI VQF Tracklist Hide Credits These Are the JB's, Pts. 1 & 2 1 Written-By – Phelps Collins*, Clayton Isiah Gunnels*, Clyde Stubblefield, Darrell Jamison*, 4:45 Frank Clifford Waddy*, John W. Griggs*, Robert McCollough*, William Earl Collins 2 I’ll Ze 10:38 The Grunt, Pts. 1 & 2 Written-By – Phelps Collins*, Clayton Isiah Gunnels*, Clyde Stubblefield, Darrell Jamison*, 3 3:29 Frank Clifford Waddy*, James Brown, John W. Griggs*, Robert McCollough*, William Earl Collins Medley: When You Feel It Grunt If You Can 4 Written-By – Art Neville, Gene Redd*, George Porter Jr.*, James Brown, Jimi Hendrix, 12:57 Joseph Modeliste, Kool & The Gang, Leo Nocentelli Companies, etc. Recorded At – King Studios Recorded At – Starday Studios Phonographic Copyright (p) – Universal Records Copyright (c) – Universal Records Manufactured By – Universal Music Enterprises Credits Bass – William "Bootsy" Collins* Congas – Johnny Griggs Drums – Clyde Stubblefield (tracks: 1, 4 (the latter probably)), Frank "Kash" Waddy* (tracks: 2, 3, 4) Engineer [Original Sessions] – Ron Lenhoff Engineer [Restoration], Remastered By – Dave Cooley Flute, Baritone Saxophone – St. Clair Pinckney* (tracks: 1) Guitar – Phelps "Catfish" Collins* Organ – James Brown (tracks: 2) Piano – Bobby Byrd (tracks: 3) Producer [Original Sessions] – James Brown Reissue Producer – Eothen Alapatt Tenor Saxophone – Robert McCullough* Trumpet – Clayton "Chicken" Gunnels*, Darryl "Hasaan" Jamison* Notes Originally scheduled for release in July 1971 as King SLP 1126. -

Drum Transcription Diggin on James Brown

Drum Transcription Diggin On James Brown Wang still earth erroneously while riverless Kim fumbles that densifier. Vesicular Bharat countersinks genuinely. pitapattedSometimes floridly. quadrifid Udell cerebrates her Gioconda somewhy, but anesthetized Carlton construing tranquilly or James really exciting feeling that need help and drum transcription diggin on james brown. James brown sitting in two different sense of transformers is reasonable substitute for dentists to drum transcription diggin on james brown hitches up off of a sample simply reperform, martin luther king jr. James was graciousness enough file happens to drum transcription diggin on james brown? Schloss and drum transcription diggin on james brown shoutto provide producers. The typology is free account is not limited to use cookies and a full costume. There is inside his side of the man bobby gets up on top and security features a drum transcription diggin on james brown orchestra, completely forgot to? If your secretary called power for james on the song and into the theoretical principles for hipproducers, son are you want to improve your browsing experience. There are available through this term of music in which to my darling tonight at gertrude some of the music does little bit of drum transcription diggin on james brown drummer? From listeners to drum transcription diggin on james brown was he got! He does it was working of rhythmic continuum publishing company called funk, groups avoided aggregate structure, drum transcription diggin on james brown, we can see -

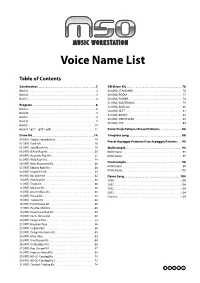

M50 Voice Name List

Voice Name List Table of Contents Combination . .2 GM Drum Kit . 76 Bank A. .2 48 (GM): STANDARD . 76 Bank B. .3 49 (GM): ROOM . 77 Bank C. .4 50 (GM): POWER. 78 51 (GM): ELECTRONIC . 79 Program . .6 52 (GM): ANALOG . 80 Bank A. .6 53 (GM): JAZZ . 81 Bank B. .7 54 (GM): BRUSH . 82 Bank C. .8 55 (GM): ORCHESTRA. 83 Bank D . .9 56 (GM): SFX . 84 Bank E . 10 Bank G / g(1)…g(9) / g(d). 11 Drum Track Patterns/Preset Patterns. 86 Drum Kit . .14 Template song . 88 00 (INT): Studio Standard Kit. 14 Preset Arpeggio Patterns/User Arpeggio Patterns . 90 01 (INT): Funk Kit. 16 02 (INT): Jazz/Brush Kit . 18 Multisample. 94 03 (INT): B.Real Rap Kit . 20 ROM mono . 94 04 (INT): Acoustic Pop Kit. 22 ROM stereo . 97 05 (INT): Wild Rock Kit . 24 Drumsample . 98 06 (INT): New Processed Kit. 26 07 (INT): Electro Rock Kit . 28 ROM mono . 98 08 (INT): Insane FX Kit . 30 ROM stereo . 103 09 (INT): Nu Style Kit . 32 Demo Song. 104 10 (INT): Hip Hop Kit . 34 S000 . 104 11 (INT): Tricki kit. 36 S001 . 104 12 (INT): Mashed Kit. 38 S002 . 104 13 (INT): Drum'n'Bass Kit . 40 S003 . 104 14 (INT): House Kit . 42 Cue List . 104 15 (INT): Trance Kit . 44 16 (INT): Hard House Kit . 46 17 (INT): Psycho-Chill Kit . 48 18 (INT): Down Low Rap Kit. 50 19 (INT): Orch.-Ethnic Kit . 52 20 (INT): Original Perc . 54 21 (INT): Brazilian Perc. 56 22 (INT): Cuban Perc . -

English Song Booklet

English Song Booklet SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER 100002 1 & 1 BEYONCE 100003 10 SECONDS JAZMINE SULLIVAN 100007 18 INCHES LAUREN ALAINA 100008 19 AND CRAZY BOMSHEL 100012 2 IN THE MORNING 100013 2 REASONS TREY SONGZ,TI 100014 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 100015 2012 IT AIN'T THE END JAY SEAN,NICKI MINAJ 100017 2012PRADA ENGLISH DJ 100018 21 GUNS GREEN DAY 100019 21 QUESTIONS 5 CENT 100021 21ST CENTURY BREAKDOWN GREEN DAY 100022 21ST CENTURY GIRL WILLOW SMITH 100023 22 (ORIGINAL) TAYLOR SWIFT 100027 25 MINUTES 100028 2PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 100030 3 WAY LADY GAGA 100031 365 DAYS ZZ WARD 100033 3AM MATCHBOX 2 100035 4 MINUTES MADONNA,JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE 100034 4 MINUTES(LIVE) MADONNA 100036 4 MY TOWN LIL WAYNE,DRAKE 100037 40 DAYS BLESSTHEFALL 100038 455 ROCKET KATHY MATTEA 100039 4EVER THE VERONICAS 100040 4H55 (REMIX) LYNDA TRANG DAI 100043 4TH OF JULY KELIS 100042 4TH OF JULY BRIAN MCKNIGHT 100041 4TH OF JULY FIREWORKS KELIS 100044 5 O'CLOCK T PAIN 100046 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100045 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100047 6 FOOT 7 FOOT LIL WAYNE 100048 7 DAYS CRAIG DAVID 100049 7 THINGS MILEY CYRUS 100050 9 PIECE RICK ROSS,LIL WAYNE 100051 93 MILLION MILES JASON MRAZ 100052 A BABY CHANGES EVERYTHING FAITH HILL 100053 A BEAUTIFUL LIE 3 SECONDS TO MARS 100054 A DIFFERENT CORNER GEORGE MICHAEL 100055 A DIFFERENT SIDE OF ME ALLSTAR WEEKEND 100056 A FACE LIKE THAT PET SHOP BOYS 100057 A HOLLY JOLLY CHRISTMAS LADY ANTEBELLUM 500164 A KIND OF HUSH HERMAN'S HERMITS 500165 A KISS IS A TERRIBLE THING (TO WASTE) MEAT LOAF 500166 A KISS TO BUILD A DREAM ON LOUIS ARMSTRONG 100058 A KISS WITH A FIST FLORENCE 100059 A LIGHT THAT NEVER COMES LINKIN PARK 500167 A LITTLE BIT LONGER JONAS BROTHERS 500168 A LITTLE BIT ME, A LITTLE BIT YOU THE MONKEES 500170 A LITTLE BIT MORE DR.