Resources and Collections Associated with the Peirce Edition Project the Max H. Fisch Library Is a Large and Complex Cluster Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Prologue to Charles Sanders Peirce's Theory of Signs

In Lieu of Saussure: A Prologue to Charles Sanders Peirce’s Theory of Signs E. San Juan, Jr. Language is as old as consciousness, language is practical consciousness that exists also for other men, and for that reason alone it really exists for me personally as well; language, like consciousness, only arises from the need, the necessity, of intercourse with other men. – Karl Marx, The German Ideology (1845-46) General principles are really operative in nature. Words [such as Patrick Henry’s on liberty] then do produce physical effects. It is madness to deny it. The very denial of it involves a belief in it. – C.S. Peirce, Harvard Lectures on Pragmatism (1903) The era of Saussure is dying, the epoch of Peirce is just struggling to be born. Although pragmatism has been experiencing a renaissance in philosophy in general in the last few decades, Charles Sanders Peirce, the “inventor” of this anti-Cartesian, scientific- realist method of clarifying meaning, still remains unacknowledged as a seminal genius, a polymath master-thinker. William James’s vulgarized version has overshadowed Peirce’s highly original theory of “pragmaticism” grounded on a singular conception of semiotics. Now recognized as more comprehensive and heuristically fertile than Saussure’s binary semiology (the foundation of post-structuralist textualisms) which Cold War politics endorsed and popularized, Peirce’s “semeiotics” (his preferred rubric) is bound to exert a profound revolutionary influence. Peirce’s triadic sign-theory operates within a critical- realist framework opposed to nominalism and relativist nihilism (Liszka 1996). I endeavor to outline here a general schema of Peirce’s semeiotics and initiate a hypothetical frame for interpreting Michael Ondaatje’s Anil’s’ Ghost, an exploratory or Copyright © 2012 by E. -

A Philosophical Commentary on Cs Peirce's “On a New List

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts A PHILOSOPHICAL COMMENTARY ON C. S. PEIRCE'S \ON A NEW LIST OF CATEGORIES": EXHIBITING LOGICAL STRUCTURE AND ABIDING RELEVANCE A Dissertation in Philosophy by Masato Ishida °c 2009 Masato Ishida Submitted in Partial Ful¯lment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2009 The dissertation of Masato Ishida was reviewed and approved¤ by the following: Vincent M. Colapietro Professor of Philosophy Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Dennis Schmidt Professor of Philosophy Christopher P. Long Associate Professor of Philosophy Director of Graduate Studies for the Department of Philosophy Stephen G. Simpson Professor of Mathematics ¤ Signatures are on ¯le in the Graduate School. ii ABSTRACT This dissertation focuses on C. S. Peirce's relatively early paper \On a New List of Categories"(1867). The entire dissertation is devoted to an extensive and in-depth analysis of this single paper in the form of commentary. All ¯fteen sections of the New List are examined. Rather than considering the textual genesis of the New List, or situating the work narrowly in the early philosophy of Peirce, as previous scholarship has done, this work pursues the genuine philosophical content of the New List, while paying attention to the later philosophy of Peirce as well. Immanuel Kant's Critique of Pure Reason is also taken into serious account, to which Peirce contrasted his new theory of categories. iii Table of Contents List of Figures . ix Acknowledgements . xi General Introduction 1 The Subject of the Dissertation . 1 Features of the Dissertation . -

Peirce for Whitehead Handbook

For M. Weber (ed.): Handbook of Whiteheadian Process Thought Ontos Verlag, Frankfurt, 2008, vol. 2, 481-487 Charles S. Peirce (1839-1914) By Jaime Nubiola1 1. Brief Vita Charles Sanders Peirce [pronounced "purse"], was born on 10 September 1839 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to Sarah and Benjamin Peirce. His family was already academically distinguished, his father being a professor of astronomy and mathematics at Harvard. Though Charles himself received a graduate degree in chemistry from Harvard University, he never succeeded in obtaining a tenured academic position. Peirce's academic ambitions were frustrated in part by his difficult —perhaps manic-depressive— personality, combined with the scandal surrounding his second marriage, which he contracted soon after his divorce from Harriet Melusina Fay. He undertook a career as a scientist for the United States Coast Survey (1859- 1891), working especially in geodesy and in pendulum determinations. From 1879 through 1884, he was a part-time lecturer in Logic at Johns Hopkins University. In 1887, Peirce moved with his second wife, Juliette Froissy, to Milford, Pennsylvania, where in 1914, after 26 years of prolific and intense writing, he died of cancer. He had no children. Peirce published two books, Photometric Researches (1878) and Studies in Logic (1883), and a large number of papers in journals in widely differing areas. His manuscripts, a great many of which remain unpublished, run to some 100,000 pages. In 1931-58, a selection of his writings was arranged thematically and published in eight volumes as the Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce. Beginning in 1982, a number of volumes have been published in the series A Chronological Edition, which will ultimately consist of thirty volumes. -

Peirce, Pragmatism, and the Right Way of Thinking

SANDIA REPORT SAND2011-5583 Unlimited Release Printed August 2011 Peirce, Pragmatism, and The Right Way of Thinking Philip L. Campbell Prepared by Sandia National Laboratories Albuquerque, New Mexico 87185 and Livermore, California 94550 Sandia National Laboratories is a multi-program laboratory managed and operated by Sandia Corporation, a wholly owned subsidiary of Lockheed Martin Corporation, for the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration under Contract DE-AC04-94AL85000.. Approved for public release; further dissemination unlimited. Issued by Sandia National Laboratories, operated for the United States Department of Energy by Sandia Corporation. NOTICE: This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government, nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, nor any of their contractors, subcontractors, or their employees, make any warranty, express or implied, or assume any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represent that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily con- stitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government, any agency thereof, or any of their contractors or subcontractors. The views and opinions expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government, any agency thereof, or any of their contractors. Printed in the United States of America. This report has been reproduced directly from the best available copy. -

Charles S. Peirce's Conservative Progressivism

Charles S. Peirce's Conservative Progressivism Author: Yael Levin Hungerford Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:107167 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2016 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Charles S. Peirce’s Conservative Progressivism Yael Levin Hungerford A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the department of Political Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Boston College Morrissey College of Arts and Sciences Graduate School June 2016 © copyright 2016 Yael Levin Hungerford CHARLES S. PEIRCE’S CONSERVATIVE PROGRESSIVISM Yael Levin Hungerford Advisor: Nasser Behnegar My dissertation explores the epistemological and political thought of Charles S. Peirce, the founder of American pragmatism. In contrast to the pragmatists who followed, Peirce defends a realist notion of truth. He seeks to provide a framework for understanding the nature of knowledge that does justice to our commonsense experience of things. Similarly in contrast to his fellow pragmatists, Peirce has a conservative practical teaching: he warns against combining theory and practice out of concern that each will corrupt the other. The first three chapters of this dissertation examine Peirce’s pragmatism and related features of his thought: his Critical Common-Sensism, Scholastic Realism, semeiotics, and a part of his metaphysical or cosmological musings. The fourth chapter explores Peirce’s warning that theory and practice ought to be kept separate. The fifth chapter aims to shed light on Peirce’s practical conservatism by exploring the liberal arts education he recommends for educating future statesmen. -

Charles Sanders Peirce - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia 9/2/10 4:55 PM

Charles Sanders Peirce - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 9/2/10 4:55 PM Charles Sanders Peirce From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Charles Sanders Peirce (pronounced /ˈpɜrs/ purse[1]) Charles Sanders Peirce (September 10, 1839 – April 19, 1914) was an American philosopher, logician, mathematician, and scientist, born in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Peirce was educated as a chemist and employed as a scientist for 30 years. It is largely his contributions to logic, mathematics, philosophy, and semiotics (and his founding of pragmatism) that are appreciated today. In 1934, the philosopher Paul Weiss called Peirce "the most original and versatile of American philosophers and America's greatest logician".[2] An innovator in many fields (including philosophy of science, epistemology, metaphysics, mathematics, statistics, research methodology, and the design of experiments in astronomy, geophysics, and psychology) Peirce considered himself a logician first and foremost. He made major contributions to logic, but logic for him encompassed much of that which is now called epistemology and philosophy of science. He saw logic as the Charles Sanders Peirce formal branch of semiotics, of which he is a founder. As early as 1886 he saw that logical operations could be carried out by Born September 10, 1839 electrical switching circuits, an idea used decades later to Cambridge, Massachusetts produce digital computers.[3] Died April 19, 1914 (aged 74) Milford, Pennsylvania Contents Nationality American 1 Life Fields Logic, Mathematics, 1.1 United States Coast Survey Statistics, Philosophy, 1.2 Johns Hopkins University Metrology, Chemistry 1.3 Poverty Religious Episcopal but 2 Reception 3 Works stance unconventional 4 Mathematics 4.1 Mathematics of logic C. -

Peirce on the Medievals: Realism, Power and Form Peirce Acerca Dos Medievais: Realismo, Poder E Forma

Peirce on the Medievals: Realism, Power and Form Peirce acerca dos Medievais: Realismo, Poder e Forma John Boler University of Washington [email protected] Abstract: In the first section, I discuss Peirce’s ambivalence attitude towards medieval thinkers – some high praise, some harsh criticism. In the second, I consider three criticisms Max Fisch mde of my book Charles Peirce and Scholastic Realism. My book had presented Peirce’s realism as if it were a single position from first to last. And I want to adjust that in the light of Fisch’s points. I now want to distinguish his scholastic realism from his on- going development of realism. To this end, I offer a more restricted and precise meaning to “scholastic realism” – roughly an anti-platonism in which the common nature is found as an element in things. That meaning does, I think, remain constant for Peirce; though I agree with Fisch that this is only a part of his developing realism. In the third section, I bring out the connection between the scholastic notion of potentiality and Peirce’s “would- be’s.” Interestingly enough (to me), this is not an influence that Peirce himself acknowledges. I also point out there that Peirce is rather dismissive of the scholastic notion of form, which he thinks is a perversion of Aristotle’s more useful (if vague) position. Keywords: Realism. Potentiality. Form. Matter. Resumo: Na primeira seção, discuto a atitude ambivalente de Peirce para com os pensadores medievais – algumas avaliações elogiosas, algumas críticas duras. Na segunda parte, considero três críticas feitas por Max Fisch ao meu livro Charles Peirce and Scholastic Realism. -

History of ENIAC

A Short History of the Second American Revolution by Dilys Winegrad and Atsushi Akera (1) Today, the northeast corner of the old Moore School building at the University of Pennsylvania houses a bank of advanced computing workstations maintained by the professional staff of the Computing and Educational Technology Service of Penn's School of Engineering and Applied Science. There, fifty years ago, in a larger room with drab- colored walls and open rafters, stood the first general purpose electronic computer, the Electronic Numerical Integrator And Computer, or ENIAC. It spanned 150 feet in width with twenty banks of flashing lights indicating the results of its computations. ENIAC could add 5,000 numbers or do fourteen 10-digit multiplications in a second-- dead slow by present-day standards, but fast compared with the same task performed on a hand calculator. The fastest mechanical relay computers being operated experimentally at Harvard, Bell Laboratories, and elsewhere could do no more than 15 to 50 additions per second, a full two orders of magnitude slower. By showing that electronic computing circuitry could actually work, ENIAC paved the way for the modern computing industry that stands as its great legacy. ENIAC was by no means the first computer. In 1839, an Englishman Charles Babbage designed and developed the first true mechanical digital computer, which he described as a "difference engine," for solving mathematical problems including simple differential equations. He was assisted in his work by a woman mathematician, Ada Countess Lovelace, a member of the aristocracy and the daughter of Lord Byron. They worked out the mathematics of mechanical computation, which, in turn, led Babbage to design the more ambitious analytical engine. -

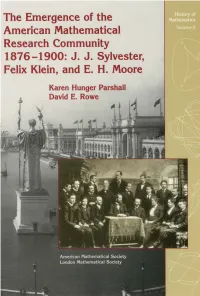

View This Volume's Front and Back Matter

Titles in This Series Volume 8 Kare n Hunger Parshall and David £. Rowe The emergenc e o f th e America n mathematica l researc h community , 1876-1900: J . J. Sylvester, Felix Klein, and E. H. Moore 1994 7 Hen k J. M. Bos Lectures in the history of mathematic s 1993 6 Smilk a Zdravkovska and Peter L. Duren, Editors Golden years of Moscow mathematic s 1993 5 Georg e W. Mackey The scop e an d histor y o f commutativ e an d noncommutativ e harmoni c analysis 1992 4 Charle s W. McArthur Operations analysis in the U.S. Army Eighth Air Force in World War II 1990 3 Pete r L. Duren, editor, et al. A century of mathematics in America, part III 1989 2 Pete r L. Duren, editor, et al. A century of mathematics in America, part II 1989 1 Pete r L. Duren, editor, et al. A century of mathematics in America, part I 1988 This page intentionally left blank https://doi.org/10.1090/hmath/008 History of Mathematics Volume 8 The Emergence o f the American Mathematical Research Community, 1876-1900: J . J. Sylvester, Felix Klein, and E. H. Moor e Karen Hunger Parshall David E. Rowe American Mathematical Societ y London Mathematical Societ y 1991 Mathematics Subject Classification. Primary 01A55 , 01A72, 01A73; Secondary 01A60 , 01A74, 01A80. Photographs o n th e cove r ar e (clockwis e fro m right ) th e Gottinge n Mathematisch e Ges - selschafft, Feli x Klein, J. J. Sylvester, and E. H. Moore. -

CSHPM Bulletin, November 2016

BULLETIN November/Novembre 2016 Number/le num´ero 59 WHAT’S INSIDE Articles Announcements ................................................................................................ 3 Interact with MAA Convergence [Janet Beery] .............................................................. 7 Joint AMS/MAA Meetings in Atlanta........................................................................ 9 Quotations in Context [Mike Molinsky] ...................................................................... 13 Grattan-Guinness Archival Research Travel Grants [Karen Parshall] ...................................... 14 Ohio Section 100th Annual Meeting [David Kullman]....................................................... 18 Three Societies in Edmonton [David Orenstein] ............................................................. 19 COMHISMA12 in Marrakech [Gregg de Young] ............................................................. 20 Jim Kiernan (1949–2014) [Walter Meyer]..................................................................... 22 Reports From the President [Dirk Schlimm] ........................................................................... 2 Executive Council Meeting CSHPM/ SCHPM............................................................... 9 2017 Call for Papers............................................................................................ 10 Annual General Meeting HSSFC [Amy Ackerberg-Hastings] ............................................... 15 AGM of CSHPM/SCHPM [Patricia Allaire] ................................................................ -

What Hath ENIAC Wrought?

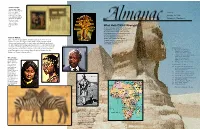

Historic Images At near right, pages from The Four Gospels, a treasure of the Tuesday, Vatican Collection. King Tut, to the right January 30, 1996 of it, and the Sphinx on the cover, are among Volume 42, Number 18 the images most requested via the African Studies Program’s Web site. What Hath ENIAC Wrought? As the celebration of its 50th Anniversary counts down to February 14, this issue presents a short history of the invention that changed world communications (pp. 4-7), and two Compass features on one of the most popular offspring of Out of Africa ENIAC: the Penn African Studies Over 250,000 times a month, someone calls up the Penn African Program’s online resource (pp. 8-9). Studies Program Web Page, rich in images of the vast and varied Please see the back cover for African continent as well as in texts, maps and scholarly exchanges. more images of Africa. As described in the Compass feature on pages 8-9, the Program is now © The Smithsonian 1994 a resource for Philadelphia teachers as well as for advanced scholars throughout the world. These samples, necessarily in black and white, In this Issue show some of the range that has brought commendation from the 2 Bulletins; PPSA Notice; Chair for Dr. Doherty; Library of Congress among others. Penn's Way Final Figures 3 Thanks to the Blizzard Crews; New JA: Dr. Perlmutter Africa Today Careers in Academia; Stunning in color HERS for Penn Women on the Web are women from the 4 ENIAC at 50: A Short History Afar region of 8-12 Compass Features Ethiopia, near right, and from 8-9 The Best On-line Resource the Djbouti on Africa; Local Schools Access Republic,wearing Africa through Penn typical jewelry. -

Carolyn Eisele's Place in Peirce Studies 327 from Mathematics and Science

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector HISTORIA MATHEMATICA 9 (1982) 326-332 CAROLYNEISELE'S PLACE IN PEIRCE STUDIES BY KENNETH LAINE KETNER INSTITUTE FOR STUDIES IN PRAGMATICISM, TEXAS TECH UNIVERSITY, LUBBOCK, TEXAS 79409 SUMMARIES Carolyn Eisele's unique, ongoing career as a scholar is sketched, and the importance of her contributions to Peirce Studies and other fields is emphasized. The essay concludes with a series of suggestions about how to interpret Peirce's works based on themes related to the pioneering efforts of Dr. Eisele. Carolyn Eisele poursuit une carribre originale dont nous prdsentons un aperqu. Nous mettons en 6vidence l'importance de sa contribution 2 notre connaissance de Peirce ainsi que son apport dans d'autres domaines. Notre essai se conclue par une sbrie de suggestions sur l'interpr&tation que l'on peut donner aux oeuvres de Peirce en se basant sur quelques th&nes issus des efforts de cette pionniere qu'est Carolyn Eisele. Es wird die einzigartige Karriere von Carolyn Eisele als Wissenschaftlerin skizziert und dabei die Bedeutung ihrer Beitr;ige zu Peirce-Studien wie auf anderen Gebieten betont. Der Essay schliei3t tit einer Reihe von Vorschllgen dazu, wie die Werke von Peirce in Verbindung mit den bahnbrechenden Bemiihungen von Frau Dr. Eisele zu interpretieren seien. The essays collected here honor two remarkable American scholarly careers, those of Charles Sanders (some add Santiago) Peirce and of a major interpreter of Peirce's works, Carolyn Eisele. We intersect with Eisele's career at a time when she has completed two major projects--her edition of Peirce's math- ematical works in The New Elements of Mathematics by Charles S.