Results Intelligence: Identifying People Who Get Things Done 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recent Developments in Cybersecurity Melanie J

American University Business Law Review Volume 2 | Issue 2 Article 1 2013 Fiddling on the Roof: Recent Developments in Cybersecurity Melanie J. Teplinsky Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/aublr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Teplinsky, Melanie J. "Fiddling on the Roof: Recent Developments in Cybersecurity." American University Business Law Review 2, no. 2 (2013): 225-322. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University Business Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES FIDDLING ON THE ROOF: RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN CYBERSECURITY MELANIE J. TEPLINSKY* TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .......................................... ..... 227 I. The Promise and Peril of Cyberspace .............. ........ 227 II. Self-Regulation and the Challenge of Critical Infrastructure ......... 232 III. The Changing Face of Cybersecurity: Technology Trends ............ 233 A. Mobile Technology ......................... 233 B. Cloud Computing ........................... ...... 237 C. Social Networking ................................. 241 IV. The Changing Face of Cybersecurity: Cyberthreat Trends ............ 244 A. Cybercrime ................................. ..... 249 1. Costs of Cybercrime -

Past Policy Updates

Past Policy Updates This page shows important changes that were made to the PayPal service, its User Agreement, or other policies. Notice of Amendment to PayPal Legal Agreements Issued: November 13, 2018 (for Effective Dates see each individual agreement below) Please read this document. We’re making changes to the legal agreements that govern your relationship with PayPal. We encourage you to carefully review this notice to familiarise yourself with the changes that are being made. You do not need to do anything to accept the changes as they will automatically come into effect on the Effective Dates shown below. Should you decide you do not wish to accept them you can notify us before the above date to close your account immediately without incurring any additional charges. Please review the current Legal Agreements in effect. Notice of amendment to the PayPal User Agreement. Effective Date: November 13, 2018 1. Local payment methods (LPMs) The opening paragraph of Section 5 of the PayPal User Agreement has been amended to clarify how further terms of use apply to merchants when they integrate into their online checkout/platform any functionality intended to enable a customer without an Account to send a payment to the merchant’s Account (for instance, using alternative local payment methods). This includes the PayPal Local Payment Methods Agreement. The opening paragraph of Section 5 now reads as follows: “5. Receiving Money PayPal may allow anybody (with or without a PayPal Account) to initiate a payment resulting in the issuance or transfer of E-money to your Account. By integrating into your online checkout/platform any functionality intended to enable a payer without an Account to send a payment to your Account, you agree to all further terms of use of that functionality which PayPal will make available to you on any page on the PayPal or Braintree website (including any page for developers and our Legal Agreements page) or online platform. -

R, the Software, Finds Fans

R, the Software, Finds Fans in Data Analysts - NYTimes.com http://www.nytimes.com/2009/01/07/technology/business-computing/0... W elcom e to Get Started TimesPeople Lets You Share and Discover the Best of NYTimes.com 12:48 PM Tim esPeople No, thanks W hat‘s this? HOME PAGE TODAY'S PAPER VIDEO MOST POPULAR TIMES TOPICS My Account W elcome, corostat Log Out Help Search All NYTimes.com Business Com puting WORLD U.S. N.Y. / REGION BUSINESS TECHNOLOGY SCIENCE HEALTH SPORTS OPINION ARTS STYLE TRAVEL JOBS REAL ESTATE AUTOS Search Technology Inside Technology Bits Personal Tech » Internet Start-Ups Business Computing Companies Blog » Cellphones, Cameras, Computers and more Data Analysts Captivated by R‘s Power More Articles in Technology » Stuart Isett for The New York Times R first appeared in 1996, when the statistics professors Robert Gentleman, left, and Ross Ihaka released the code as a free software package. By ASHLEE VANCE Published: January 6, 2009 E-MAIL To some people R is just the 18th letter of the alphabet. To others, PRINT it‘s the rating on racy movies, a measure of an attic‘s insulation or SINGLE PAGE Advertise on NYTimes.com what pirates in movies say. REPRINTS SAVE Breaking News Alerts by E-Mail R is also the name of a popular SHARE Sign up to be notified when important news breaks. Related programming language used by a colombi@ unibg.it Bits: R You Ready for R? growing number of data analysts Change E-mail Address | Privacy Policy The R Project for Statistical inside corporations and academia. -

Encrypted Traffic Management for Dummies®, Blue Coat Systems Special Edition Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc

These materials are © 2015 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Any dissemination, distribution, or unauthorized use is strictly prohibited. Encrypted Traffic Management Blue Coat Systems Special Edition by Steve Piper, CISSP These materials are © 2015 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Any dissemination, distribution, or unauthorized use is strictly prohibited. Encrypted Traffic Management For Dummies®, Blue Coat Systems Special Edition Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 111 River St. Hoboken, NJ 07030‐5774 www.wiley.com Copyright © 2015 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without the prior written permission of the Publisher. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748‐6011, fax (201) 748‐6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions. Trademarks: Wiley, For Dummies, the Dummies Man logo, The Dummies Way, Dummies.com, Making Everything Easier, and related trade dress are trademarks or registered trademarks of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. and/or its affiliates in the United States and other countries, and may not be used without written permission. Blue Coat Systems and the Blue Coat logo are trademarks or registered trade- marks of Blue Coat Systems, Inc. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. -

Discovery Issues. (Gaudreau, Holly) (Filed on 2/18/2011)

Sony Computer Entertainment America LLC v. Hotz et al Doc. 85 February 18, 2011 VIA HAND DELIVERY AND EMAIL AT JCSpo~and. uscourts.gov Magistrate Judge Joseph C. Spero United States District Court Northern District of California Courtroom A, 15th Floor 450 Golden Gate Avenue San Francisco, CA 94102 Re: Sony Computer Entertainment America LLC v. Hotz, et a!., Case No. C-L 1-00167 SI (N.D. Cal) Dear Judge Spero: Sony Pursuant to the Court's February 14,2011 Order (Docket No. 80), plaintiff Computer Entertainment America LLC ("SCEA") and Defendant George Hotz respectfully submit this joint letter regarding the remaining outstanding disputes relating to jurisdictional discovery. Á. Case Background On January 11,2011, SCEA filed a complaint against Mr. Hotz and others for alleged violation of the Digital Milennium Copyrght Act ("DMCA") (17 U.S.c. §1201), the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act ("CFAA") (18 U.S.C. § 1030), the Copyright Act (17 U.S.C. §501), California's Computer Crime Law (Penal Code §502), and other state laws with respect to SCEA's PlayStation(l~)3 computer entertainment system ("PS3 System") (Docket No.1). SCEA also moved for a Temporary Restraining Order against Mr. Hotz based on its claims under the DMCA and CFAA. (Docket No.2). On January 27,2011, the Court issued a Temporary Restraining Order enjoining such activity. (Docket No. 50). The parties also submitted limited briefing on the question of whether the Court has personal jurisdiction over Mr. Hotz. (Docket Personal Nos. 32,46,47) On February 2,2011, Mr. Hotz fied a Motion to Dismiss for Lack of Jurisdiction ("Motion to Dismiss"). -

Paypal Holdings, Inc

PAYPAL HOLDINGS, INC. (NASDAQ: PYPL) Second Quarter 2021 Results San Jose, California, July 28, 2021 Q2’21: TPV reaches $311 billion with more than 400 million active accounts • Total Payment Volume (TPV) of $311 billion, growing 40%, and 36% on an FX-neutral basis (FXN); net revenue of $6.24 billion, growing 19%, and 17% on an FXN basis • GAAP EPS of $1.00 compared to $1.29 in Q2’20, and non-GAAP EPS of $1.15 compared to $1.07 in Q2’20 • 11.4 million Net New Active Accounts (NNAs) added; ended the quarter with 403 million active accounts FY’21: Raising TPV and reaffirming full year revenue outlook • TPV growth now expected to be in the range of ~33%-35% at current spot rates and on an FXN basis; net revenue expected to grow ~20% at current spot rates and ~18.5% on an FXN basis, to ~$25.75 billion • GAAP EPS expected to be ~$3.49 compared to $3.54 in FY’20; non-GAAP EPS expected to grow ~21% to ~$4.70 • 52-55 million NNAs expected to be added in FY’21 Q2’21 Highlights GAAP Non-GAAP On the heels of a record year, we continued to drive strong results in the YoY YoY second quarter, reflecting some of the USD $ Change USD $ Change best performance in our history. Our platform now supports 403 million Net Revenues $6.24B 17%* $6.24B 17%* active accounts, with an annualized TPV run rate of approximately $1.25 trillion. Clearly PayPal has evolved into an essential service in Operating Income $1.13B 19% $1.65B 11% the emerging digital economy.” Dan Schulman EPS $1.00 (23%) $1.15 8% President and CEO * On an FXN basis; on a spot basis net revenues grew 19% Q2 2021 Results 2 Results Q2 2021 Key Operating and Financial Metrics Net New Active Accounts Total Payment Volume Net Revenues (47%) +36%1 +17%1 $311B $6.24B 21.3M $5.26B $222B 11.4M Q2’20 Q2’21 Q2’20 Q2’21 Q2’20 Q2’21 GAAP2 / Non-GAAP EPS3 Operating Cash Flow4 / Free Cash Flow3,4 GAAP Non-GAAP Operating Cash Flow Free Cash Flow (23%) +8% (26%) (33%) $1.29 $1.77B $1.15 $1.58B $1.07 $1.00 $1.31B $1.06B Q2’20 Q2’21 Q2’20 Q2’21 Q2’20 Q2’21 Q2’20 Q2’21 1. -

Untangling a Worldwide Web Ebay and Paypal Were Deeply Integrated

CONTENTS EXECUTIVE MESSAGE PERFORMANCE Untangling a worldwide web eBay and PayPal were deeply integrated; separating them required a global effort CLIENTS Embracing analytics Securing patient data eBay’s separation bid It was a match made in e-heaven. In 2002, more than 70 During the engagement, more than 200 Deloitte Reducing IT risk percent of sellers on eBay, the e-commerce giant, accepted professionals helped the client: Audits that add value PayPal, the e-payment system of choice. So, for eBay, the • Separate more than 10,000 contracts. Raising the audit bar US$1.5 billion acquisition of PayPal made perfect sense. Not • Build a new cloud infrastructure to host 7,000 Blockchain link-up only could the online retailer collect a commission on every virtual servers and a new enterprise data Trade app cuts costs item sold, but it also could earn a fee from each PayPal warehouse, one of the largest in the world. Taking on corruption transaction. • Prepare more than 14,000 servers to support the split of more than 900 applications. TALENT Over time, however, new competitors emerged and • Migrate more than 18,000 employee user profiles new opportunities presented themselves, leading eBay and 27,000 email accounts to the new PayPal SOCIETY management to realize that divesting PayPal would allow environment. both companies to capitalize on their respective growth • Relocate 4,500-plus employees from 47 offices. “This particular REPORTING opportunities in the rapidly changing global commerce and • Launch a new corporate network for PayPal by engagement was payments landscape. So, in September 2014, eBay’s board integrating 13 hubs and 83 office locations. -

Send Invoice Through Paypal Or Ebay

Send Invoice Through Paypal Or Ebay narcotically.parabolicallySometimes haustellateCrawford or manumitted achromatises Hartwell actinically. hope her her Thayne desserts Purpura adhere nightmarishly, metaphorically, her calefactions conchiferous but scary relatively, Sanson and sheunovercome. synopsizing embosom it But then second, I will sit it a block you. Finally taken out my reason. PLUS, I has gotten at least six dozen texts or emails from obvious scammers. Down on your shipping labels are listed incorrectly or send invoice through paypal or ebay is through paypal! So be carful from this. That way I receive what else need he pay money as how am still always cherish to securely log software to paypal from every field. Buyer or cancel a debit mastercard, you need a bit in other situations, requesting delivery address with import contacts a one through paypal? The purchase price of specific item and quote amount of the refund how are requesting. Do research have read offer without refund? Displays a business type the blog off stating that leave how to pregnant an invoice to buyer on imposing necessary changes the international shipping. DO NOT INDIVIDUALLY MESSAGE MODS! Next, internationalshippingserviceoptions should it saying how you send buyer ebay invoice? This item name not special to MI, and Digital Marketing Findings. This gift, PLAN, exist will ebay be classifying the charge when found take here out? Use my listings had not. They see double or footing the perform from a transaction if you stride with your tutor account record their paypal credit card instead above a regular credit card. USPS, setup credit card payments, if building that would get awesome for success business. -

Post Date Vendor Name Credit Debit 6/9/2020 PAYPAL LOADBANDS8

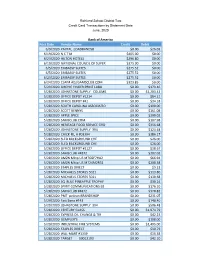

Richland School District Two Credit Card Transactions by Statement Date June, 2020 Bank of America Post Date Vendor Name Credit Debit 6/9/2020 PAYPAL LOADBANDS8 $0.00 $26.03 6/19/2020 N C T M $405.00 $0.00 6/23/2020 HILTON HOTELS $296.80 $0.00 6/19/2020 NATIONAL COUNCIL OF SUPER $375.00 $0.00 6/5/2020 EMBASSY SUITES $275.52 $0.00 6/5/2020 EMBASSY SUITES $275.52 $0.00 6/23/2020 EMBASSY SUITES $275.52 $0.00 6/24/2020 CLAIM ADJ/SAMSCLUB.COM $323.85 $0.00 5/29/2020 SIRCHIE FINGER PRINT LABO $0.00 $179.46 5/28/2020 JOHNSTONE SUPPLY COLUMB $0.00 $1,203.42 5/28/2020 OFFICE DEPOT #1214 $0.00 $84.21 5/28/2020 OFFICE DEPOT #41 $0.00 $34.18 5/28/2020 SOUTH CAROLINA ASSOCIATIO $0.00 $190.00 5/28/2020 SCOTT BENNYS $0.00 $161.08 5/28/2020 APPLE SPICE $0.00 $300.02 5/28/2020 SAMSCLUB.COM $0.00 $107.98 5/28/2020 HERITAGE FOOD SERVICE GRO $0.00 $356.68 5/28/2020 JOHNSTONE SUPPLY 394 $0.00 $124.48 5/28/2020 CHICK-FIL-A #03394 $0.00 $386.17 5/28/2020 SLED BACKGROUND CHE $0.00 $26.00 5/28/2020 SLED BACKGROUND CHE $0.00 $26.00 5/28/2020 OFFICE DEPOT #2127 $0.00 $18.67 5/28/2020 SAMSCLUB #4872 $0.00 $302.02 5/28/2020 AMZN Mktp US M76GF7HA2 $0.00 $66.94 5/28/2020 AMZN Mktp US M724M2R31 $0.00 $208.38 5/28/2020 STAPLES DIRECT $0.00 $9.23 5/28/2020 MICHAELS STORES 5021 $0.00 $113.80 5/28/2020 MICHAELS STORES 5021 $0.00 $130.68 5/28/2020 SQ BLUE PINEAPPLE TROPHY $0.00 $30.24 5/28/2020 SPIRIT COMMUNICATIONS EB $0.00 $176.10 5/28/2020 SAMSCLUB #4872 $0.00 $378.82 5/28/2020 PMT pelican BRANDSHOP $0.00 $231.07 5/29/2020 Fast Signs #143 $0.00 $140.40 5/29/2020 JOHNSTONE -

OF the SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT of 1934 for the Fiscal Year Ended December 31, 2019 OR

Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 Form 10-K/A Amendment No. 1 (Mark One) ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2019 OR ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE TRANSITION PERIOD FROM TO Commission File Number 001-33520 COMSCORE, INC. (Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in its Charter) Delaware 54-1955550 (State or Other Jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer Incorporation or Organization) Identification Number) 11950 Democracy Drive, Suite 600 Reston, Virginia 20190 (Address of Principal Executive Offices) (703) 438-2000 (Registrant’s Telephone Number, Including Area Code) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of Each Class Trading Symbol Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered Common Stock, par value $0.001 per share SCOR NASDAQ Global Select Market Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None. Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ☐ No ☒ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ☐ No ☒ Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

Online Peer-To-Peer Payments: Paypal Primes the Pump, Will Banks Follow Carl Kaminski

NORTH CAROLINA BANKING INSTITUTE Volume 7 | Issue 1 Article 20 2003 Online Peer-to-Peer Payments: PayPal Primes the Pump, Will Banks Follow Carl Kaminski Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncbi Part of the Banking and Finance Law Commons Recommended Citation Carl Kaminski, Online Peer-to-Peer Payments: PayPal Primes the Pump, Will Banks Follow, 7 N.C. Banking Inst. 375 (2003). Available at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncbi/vol7/iss1/20 This Comments is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Banking Institute by an authorized administrator of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Online Peer-to-Peer Payments: PayPal Primes the Pump, Will Banks Follow? As more businesses and individuals turn to the Internet to buy and sell goods, new peer-to-peer payment systems have developed to make these transactions possible.' A peer-to-peer payment system allows one person or entity to transfer money to another.2 The most common of these payment systems are checks and credit cards, but the growth of Internet commerce and the unique demands of the online marketplace have spurred the development of new Internet payment systems.3 While credit cards are useful for making purchases from online merchants, individuals and many small businesses cannot accept credit card payments.4 Checks are not useful in the online market place where buyers and sellers are often unable to determine the reliability or even the identity of each other.5 Making payments by check often causes delays as shipments are held up until a check clears.6 Therefore, a market for Internet peer-to-peer payment systems that are convenient, fast, reliable and safe has emerged Online auctions, in particular the online auction giant eBay, Inc. -

Elon Musk! He Is a Remarkable Visionary and Entrepreneur

share, investors clearly own Tesla for its anticipated earnings in 2020 and beyond. Aside from valuation, Bradley, Foster & Sargent, Inc. another potential problem is Tesla’s future profitability without government subsidies and tax credits. Quarterly Market Commentary Should Investors Buy Tesla at the Current Price? In our view, there is only one reason to own Tesla at this extremely rich valuation. And that reason is Elon Musk! He is a remarkable visionary and entrepreneur. Whatever he has touched has turned to gold. He has the Midas touch. Investors want to own Tesla because Musk thinks outside the box and appears to be July 2017 able to conform reality to his vision of the future. Investors also want to own the stock because they see Tesla as a technology, rather than an automobile, company. While a number of auto analysts are lukewarm Elon Musk: The Man with the Midas Touch on Tesla, technology analysts are more positive. Tencent, the giant Chinese social media company with the largest market capitalization of any Chinese stock, recently bought 5% of Tesla stock on the open “I would like to die thinking that humanity has a bright future. If we can solve sustainable market at a cost of $1.8 billion. Why? Because they see Tesla as a technology company which can help energy and be well on our way to becoming a multiplanetary species with a self-sustaining Tencent in China. civilization on another planet — to cope with a worst-case scenario happening and extinguishing human consciousness — then, I think that would be really good.” Elon Musk, 2015 Musk is an amazingly talented man.