Experiments with Light-Emitting Diodes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fundamentals of Microelectronics Chapter 3 Diode Circuits

9/17/2010 Fundamentals of Microelectronics CH1 Why Microelectronics? CH2 Basic Physics of Semiconductors CH3 Diode Circuits CH4 Physics of Bipolar Transistors CH5 Bipolar Amplifiers CH6 Physics of MOS Transistors CH7 CMOS Amplifiers CH8 Operational Amplifier As A Black Box 1 Chapter 3 Diode Circuits 3.1 Ideal Diode 3.2 PN Junction as a Diode 3.3 Applications of Diodes 2 1 9/17/2010 Diode Circuits After we have studied in detail the physics of a diode, it is time to study its behavior as a circuit element and its many applications. CH3 Diode Circuits 3 Diode’s Application: Cell Phone Charger An important application of diode is chargers. Diode acts as the black box (after transformer) that passes only the positive half of the stepped-down sinusoid. CH3 Diode Circuits 4 2 9/17/2010 Diode’s Action in The Black Box (Ideal Diode) The diode behaves as a short circuit during the positive half cycle (voltage across it tends to exceed zero), and an open circuit during the negative half cycle (voltage across it is less than zero). CH3 Diode Circuits 5 Ideal Diode In an ideal diode, if the voltage across it tends to exceed zero, current flows. It is analogous to a water pipe that allows water to flow in only one direction. CH3 Diode Circuits 6 3 9/17/2010 Diodes in Series Diodes cannot be connected in series randomly. For the circuits above, only a) can conduct current from A to C. CH3 Diode Circuits 7 IV Characteristics of an Ideal Diode V V R = 0⇒ I = = ∞ R = ∞⇒ I = = 0 R R If the voltage across anode and cathode is greater than zero, the resistance of an ideal diode is zero and current becomes infinite. -

Photodiode and LIGHT EMITTING DIODE

Photodiode and LIGHT EMITTING DIODE Presentation by JASWANT KUMAR ROLL NO.-12 rd IT(3 SEM.) 1 About LEDs (1/2) • A light emitting diode (LED) is essentially a PN junction opto- semiconductor that emits a monochromatic (single color) light when operated in a forward biased direction. • LEDs convert electrical energy into light energy. LED SYMBOL 2 ABOUT LEDS (2/2) • The most important part of a light emitting diode (LED) is the semi-conductor chip located in the center of the bulb as shown at the right. • The chip has two regions separated by a junction. • The junction acts as a barrier to the flow of electrons between the p and the n regions. 3 LED CIRCUIT • In electronics, the basic LED circuit is an electric power circuit used to power a light-emitting diode or LED. The simplest such circuit consists of a voltage source and two components connect in series: a current-limiting resistor (sometimes called the ballast resistor), and an LED. Optionally, a switch may be introduced to open and close the circuit. The switch may be replaced with another component or circuit to form a continuity tester. 4 HOW DOES A LED WORK? • Each time an electron recombines with a positive charge, electric potential energy is converted into electromagnetic energy. • For each recombination of a negative and a positive charge, a quantum of electromagnetic energy is emitted in the form of a photon of light with a frequency characteristic of the semi- conductor material. 5 Mechanism behind photon emission in LEDs? MechanismMechanism isis “injection“injection Electroluminescence”.Electroluminescence”. -

Integrated High-Speed, High-Sensitivity Photodiodes and Optoelectronic Integrated Circuits

Sensors and Materials, Vol. 13, No. 4 (2001) 189-206 MYUTokyo S &M0442 Integrated High-Speed, High-Sensitivity Photodiodes and Optoelectronic Integrated Circuits Horst Zimmermann Institut fiirElektrische Mess- und Schaltungstechnik, Technische Universitat Wien, Gusshausstrasse, A-1040 Wien, Austria (Received February 28, 2000; accepted February3, 2001) Key words: integrated circuits, integrated optoelectronics, optical receivers, optoelectronic de vices, PIN photodiode, double photodiode, silicon A review of the properties of photodiodes available through the use of standard silicon technologies is presented and some examples of how to improve monolithically integrated photodiodes are shown. The application of these photodiodes in optoelectronic integrated circuits (OEICs) is described. An innovative double photodiode requiring no process modificationsin complementary metal-oxide sem!conductor (CMOS) and bipolar CMOS (BiCMOS) technologies achieves a bandwidth in excess of 360 MHzand data rates exceeding 622 Mb/s. Furthermore, a new PIN photodiode requiring only one additional mask for the integration in a CMOS process is capable of handling a data rate of 1.1 Gb/s. Antireflection coating improves the quantum efficiencyof integrated photodiodes to values of more than 90%. Integrated optical receivers for data communication achieve a high bandwidth and a high sensitivity. Furthermore, an OEIC for application in optical storage systems is introduced. Author's e-mail address: [email protected] 189 l 90 Sensors and Materials, Vol. 13, No. 4 (2001) 1. Introduction Photons with an energy larger than the band gap generate electron-hole pairs in semiconductors. This photogeneration G obeys an exponential law: aP,0 G( x) = -- exp( -ax), Ahv (1) where xis the penetration depth coordinate, P0 is the nonreflectedportion of the incident optical power, A is the light-sensitive area of a photodiode, hv is the energy of the photon, and a is the wavelength-dependent absorption coefficient. -

Leds As Single-Photon Avalanche Photodiodes by Jonathan Newport, American University

LEDs as Single-Photon Avalanche Photodiodes by Jonathan Newport, American University Lab Objectives: Use a photon detector to illustrate properties of random counting experiments. Use limiting probability distributions to perform statistical analysis on a physical system. Plot histograms. Condition a detector’s signal for further electronic processing. Use a breadboard, power supply and oscilloscope to construct a circuit and make measurements. Learn about semiconductor device physics. Reading: Taylor 3.2 – The Square-Root Rule for a Counting Experiment pp. 48-49 Taylor 5.1-5.3 – Histograms and the Normal Distribution pp. 121-135 Taylor Ch. 11 – The Poisson Distribution pp. 245-254 Taylor Problem 5.6 – The Exponential Distribution p. 155 Experiment #1: Lighting an LED A Light-Emitting Diode is a non-linear circuit element that can produce a controlled amount of light. The AND113R datasheet shows that the luminous intensity is proportional to the current flowing through the LED. As illustrated in the IV curve shown below, the current flowing through the diode is in turn proportional to the voltage across the diode. Diodes behave like a one-way valve for current. When the voltage on the Anode is more positive than the voltage on the Cathode, then the diode is said to be in Forward Bias. As the voltage across the diode increases, the current through the diode increases dramatically. The heat generated by this current can easily destroy the device. It is therefore wise to install a current-limiting resistor in series with the diode to prevent thermal runaway. When the voltage on the Cathode is more positive than the voltage on the Anode, the diode is said to be in Reverse Bias. -

Vacuum Tube Theory, a Basics Tutorial – Page 1

Vacuum Tube Theory, a Basics Tutorial – Page 1 Vacuum Tubes or Thermionic Valves come in many forms including the Diode, Triode, Tetrode, Pentode, Heptode and many more. These tubes have been manufactured by the millions in years gone by and even today the basic technology finds applications in today's electronics scene. It was the vacuum tube that first opened the way to what we know as electronics today, enabling first rectifiers and then active devices to be made and used. Although Vacuum Tube technology may appear to be dated in the highly semiconductor orientated electronics industry, many Vacuum Tubes are still used today in applications ranging from vintage wireless sets to high power radio transmitters. Until recently the most widely used thermionic device was the Cathode Ray Tube that was still manufactured by the million for use in television sets, computer monitors, oscilloscopes and a variety of other electronic equipment. Concept of thermionic emission Thermionic basics The simplest form of vacuum tube is the Diode. It is ideal to use this as the first building block for explanations of the technology. It consists of two electrodes - a Cathode and an Anode held within an evacuated glass bulb, connections being made to them through the glass envelope. If a Cathode is heated, it is found that electrons from the Cathode become increasingly active and as the temperature increases they can actually leave the Cathode and enter the surrounding space. When an electron leaves the Cathode it leaves behind a positive charge, equal but opposite to that of the electron. In fact there are many millions of electrons leaving the Cathode. -

Diodes As Rectifiers +

Diodes as Rectifiers As previously mentioned, diodes can be used to convert alternating current (AC) to direct current (DC). Shown below is a representative schematic of a simple DC power supply similar to a au- tomobile battery charger. The way in which the diode rectifier is used results in what is called a half-wave rectifier. 0V 35.6Vpp 167V 0V pp 17.1Vp 0V T1 D1 Wallplug 1N4001 negative half−wave is 110VAC R1 resistive load removed by diode D1 D1 120 to 12.6VAC − stepdown transformer + D2 D2 input from RL input from RL transformer transformer (positive half−cycle) Figure 1: Half-Wave Rectifier Schematic (negative half−cycle) − D3 + D3 The input transformer steps the input voltage down from 110VAC(rms) to 12.6VAC(rms). The D4 D4 diode converts the AC voltage to DC by removing theD1 and negative D3 goingD1 and D3 part of the input sine wave. The result is a pulsating DC output waveform which is not ideal except for17.1V simplep applications 0V such as battery chargers as the voltage goes to zero for oneD2 have and D4 of every cycle. What we would D1 D1 v_out like is a DC output that is more consistent;T1 a waveform more like a battery what we have here. T1 1 D2 D2 C1 Wallplug R1 Wallplug R1 We need a way to use the negative half-cycle of theresistive sine load wave to to fill in between the pulses 50uF 1K 110VAC 110VAC created by the positive half-waves. This would give us a more consistent output voltage. -

Lecture 3: Diodes and Transistors

2.996/6.971 Biomedical Devices Design Laboratory Lecture 3: Diodes and Transistors Instructor: Hong Ma Sept. 17, 2007 Diode Behavior • Forward bias – Exponential behavior • Reverse bias I – Breakdown – Controlled breakdown Æ Zeners VZ = Zener knee voltage Compressed -VZ scale 0V 0.7 V V ⎛⎞V Breakdown V IV()= I et − 1 S ⎜⎟ ⎝⎠ kT V = t Q Types of Diode • Silicon diode (0.7V turn-on) • Schottky diode (0.3V turn-on) • LED (Light-Emitting Diode) (0.7-5V) • Photodiode • Zener • Transient Voltage Suppressor Silicon Diode • 0.7V turn-on • Important specs: – Maximum forward current – Reverse leakage current – Reverse breakdown voltage • Typical parts: Part # IF, max IR VR, max Cost 1N914 200mA 25nA at 20V 100 ~$0.007 1N4001 1A 5µA at 50V 50V ~$0.02 Schottky Diode • Metal-semiconductor junction • ~0.3V turn-on • Often used in power applications • Fast switching – no reverse recovery time • Limitation: reverse leakage current is higher – New SiC Schottky diodes have lower reverse leakage Reverse Recovery Time Test Jig Reverse Recovery Test Results • Device tested: 2N4004 diode Light Emitting Diode (LED) • Turn-on voltage from 0.7V to 5V • ~5 years ago: blue and white LEDs • Recently: high power LEDs for lighting • Need to limit current LEDs in Parallel V R ⎛⎞ Vt IV()= IS ⎜⎟ e − 1 VS = 3.3V ⎜⎟ ⎝⎠ •IS is strongly dependent on temp. • Resistance decreases R R R with increasing V = 3.3V S temperature • “Power Hogging” Photodiode • Photons generate electron-hole pairs • Apply reverse bias voltage to increase sensitivity • Key specifications: – Sensitivity -

CSE- Module-3: SEMICONDUCTOR LIGHT EMITTING DIODE :LED (5Lectures)

CSE-Module- 3:LED PHYSICS CSE- Module-3: SEMICONDUCTOR LIGHT EMITTING DIODE :LED (5Lectures) Light Emitting Diodes (LEDs) Light Emitting Diodes (LEDs) are semiconductors p-n junction operating under proper forward biased conditions and are capable of emitting external spontaneous radiations in the visible range (370 nm to 770 nm) or the nearby ultraviolet and infrared regions of the electromagnetic spectrum General Structure LEDs are special diodes that emit light when connected in a circuit. They are frequently used as “pilot light” in electronic appliances in to indicate whether the circuit is closed or not. The structure and circuit symbol is shown in Fig.1. The two wires extending below the LED epoxy enclose or the “bulb” indicate how the LED should be connected into a circuit or not. The negative side of the LED is indicated in two ways (1) by the flat side of the bulb and (2) by the shorter of the two wires extending from the LED. The negative lead should be connected to the negative terminal of a battery. LEDs operate at relative low voltage between 1 and 4 volts, and draw current between 10 and 40 milliamperes. Voltages and Fig.-1 : Structure of LED current substantially above these values can melt a LED chip. The most important part of a light emitting diode (LED) is the semiconductor chip located in the centre of the bulb and is attached to the 1 CSE-Module- 3:LED top of the anvil. The chip has two regions separated by a junction. The p- region is dominated by positive electric charges, and the n-region is dominated by negative electric charges. -

Bipolar Junction Transistor As a Detector for Measuring in Diagnostic X-Ray Beams

2013 International Nuclear Atlantic Conference - INAC 2013 Recife, PE, Brazil, November 24-29, 2013 ASSOCIAÇÃO BRASILEIRA DE ENERGIA NUCLEAR - ABEN ISBN: 978-85-99141-05-2 BIPOLAR JUNCTION TRANSISTOR AS A DETECTOR FOR MEASURING IN DIAGNOSTIC X-RAY BEAMS Francisco A. Cavalcanti1,2, David S. Monte1,2, Aline N. Alves1,2, Fábio R. Barros2, Marcus A. P. Santos2, and Luiz A. P. Santos1,2 1 Departamento de Energia Nuclear Universidade Federal de Pernambuco Av. Prof. Luiz Freire, 1000 50740-540 Recife, PE [email protected] 2 Centro Regional de Ciências Nucleares do Nordeste (CRCN-NE / CNEN) Av. Prof. Luiz Freire, 1 50740-540 Recife, PE [email protected] ABSTRACT Photodiode and phototransistor are the most frequently used devices for measuring ionizing radiation in medical applications. The cited devices have the operating principle well known, however the bipolar junction transistor (BJT) is not a typical device used as a detector for measuring some physical quantities for diagnostic radiation. In fact, a photodiode, for example, has an area about 10 mm square and a BJT has an area which can be more than 10 thousands times smaller. The purpose of this paper is to bring a new technique to estimate some physical quantities or parameters in diagnostic radiation; for example, peak kilovoltage (kVp), deep dose measurements. The methodology for each type of evaluation depends on the energy range of the radiation and the physical quantity or parameter to be measured. Actually, some characteristics of the incident radiation under the device can be correlated with the readout signal, which is a function of the electrical currents in the electrodes of the BJT: Collector, Base and Emitter. -

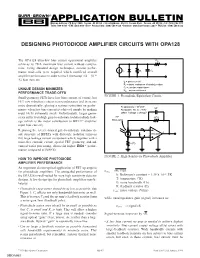

Designing Photodiode Amplifier Circuits with Opa128

® DESIGNING PHOTODIODE AMPLIFIER CIRCUITS WITH OPA128 The OPA128 ultra-low bias current operational amplifier RS achieves its 75fA maximum bias current without compro- mise. Using standard design techniques, serious perfor- I R C mance trade-offs were required which sacrificed overall P J J amplifier performance in order to reach femtoamp (fA = 10–15 A) bias currents. IP = photocurrent RJ = shunt resistance of diode junction CJ = junction capacitance UNIQUE DESIGN MINIMIZES R = series resistance PERFORMANCE TRADE-OFFS S FIGURE 1. Photodiode Equivalent Circuit. Small-geometry FETs have low bias current, of course, but FET size reduction reduces transconductance and increases noise dramatically, placing a serious restriction on perfor- Responsivity ≈ 109V/W 5pF mance when low bias current is achieved simply by making Bandwidth: DC to ≈ 30Hz input FETs extremely small. Unfortunately, larger geom- Offset Voltage ≈ ±485µV etries suffer from high gate-to-substrate isolation diode leak- HP 109Ω age (which is the major contribution to BIFET® amplifier 5082-4204 input bias current). Replacing the reverse-biased gate-to-substrate isolation di- 2 6 OPA128LM ode structure of BlFETs with dielectric isolation removes 3 this large leakage current component which, together with a 8 noise-free cascode circuit, special FET geometry, and ad- 109Ω vanced wafer processing, allows far higher Difet ® perfor- mance compared to BIFETs. FIGURE 2. High-Sensitivity Photodiode Amplifier. HOW TO IMPROVE PHOTODIODE AMPLIFIER PERFORMANCE An important electro-optical application of FET op amps is √ for photodiode amplifiers. The unequaled performance of eOUT = 4k TBR the OPA128 is well-suited for very high sensitivity detector k: Boltzman’s constant = 1.38 x 10–23 J/K ° designs. -

Cathodoluminescence in Semiconductor Structures Under Local Tunneling Electron Injection Petr Polovodov

Cathodoluminescence in semiconductor structures under local tunneling electron injection Petr Polovodov To cite this version: Petr Polovodov. Cathodoluminescence in semiconductor structures under local tunneling electron injection. Optics [physics.optics]. Ecole Doctorale de l’Ecole Polytechnique, 2015. English. tel- 01346834v2 HAL Id: tel-01346834 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01346834v2 Submitted on 23 Jul 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Thèse présentée pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR DE L'ÉCOLE POLYTECHNIQUE Spécialité : Physique Par Petr POLOVODOV Cathodoluminescence in semiconductor structures under local tunneling electron injection Soutenue le 21 décembre 2015 devant le jury composé de : M. Fabrice Charra CEA/Saclay, Gif sur Yvette Rapporteur M. Philippe Dumas CINaM, Marseille Rapporteur M. Razvigor Ossikovski LPICM, Ecole Polytechnique, Palaiseau Examinateur M. Oleg Tereshchenko Rzhanov Institute of Semiconductor Examinateur Physics, Novosibirsk, Russie M. Yves Lassailly LPMC, Ecole Polytechnique, Palaiseau Directeur de thèse M. Jacques Peretti LPMC, Ecole Polytechnique, Palaiseau Co-Directeur de thèse 2 ACNOWLEGEMENTS I have defended my PhD thesis in physics. This is the accomplishment of myself but several persons have contributed to this work. First of all, I am grateful to François Ozanam and Mathis Plapp, successive Directors of the Laboratory, who allowed me to perform my PhD work at the LPMC in the best possible conditions. -

Low-Voltage Cathodoluminescent Phosphors a 20-Year Chronology of Low-Voltage Cathodoluminescence Efficiency by Lauren E

Low-Voltage Cathodoluminescent Phosphors A 20-year chronology of low-voltage cathodoluminescence efficiency by Lauren E. Shea hosphors have been used for the display of information since the invention of the cathode-ray tube (CRT) by Karl Ferdinand Braun in 1897 (1). With the P development of color television, an effort spanning approximately thirty years, came the most significant advances in phosphor technology. The most noteworthy was the shift to the all-sulfide system, and discovery of the red, rare-earth oxysulfide phosphors 3+ (e.g., Y2O2S:Eu ) (2). White brightness efficiency of phosphor screens also improved significantly: 15 lm/W in FIG. 1. Efficiency of red phosphor powders (lettered squares) and screens (numbered diamonds) as a function of electron accelerating voltage. Y O :Eu - A, I, S (12); G (13); N (20); O, U, 5, 9 (14); W (21); YVO :Eu - B, L, 1951 to over 35 lm/W in 1979, as a 2 3 4 Q (13); F (18); P, X, 7, 10 (14); Y2O2S:Eu - C, J, R (22); D(12); H, Y (20); K, V (21); M, T, 3, 6, 11 (14); 8 result of new phosphor formulations (23); ZnCdS:Ag, In - 1 (16); ZnCdS:Ag, In + SnO2 - 2 (17); LaInO3:Eu - 4 (15); unspecified - E (18). and improved screening techniques (3). Today, a primary focus of research toire d’Electronique de Technologie et reported in earlier years, and (4) has in the area of luminescence is phosphor d’Instrumentation (LETI) (5). Many progress been made? development and improvement for FEDs are being designed for operation in ≤ low-voltage ( 1 kV) emissive flat-panel the 5-10 kV range.