The Solent a Cruising Guide for Centreboard Boats

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Upffront.Com Structural Furling Forestays

©Karver Upffront.com Structural Furling Forestays The use of continuous line furlers and torsional cables for main structural forestays 1 www.upffront.com Contents: Page No. 1. Introduction 3 2. What is a “Structural Furling Forestay”? 3 a. Description 3 b. Advantages 5 c. Perceived disadvantages 8 3. Wire vs composite furling forestay 10 4. Deck and mast interfaces a. Fixed forestay length 11 b. Toggles or strops 11 12 5. Sail interfaces 13 a. Luff 13 b. Hoist 14 6. Specifying considerations 15 7. Conclusion 14 2 www.upffront.com 1. Introduction In this document you will be introduced to the use of continuous line furlers, together with torsional cables, as an alternative furling system for the main structural forestay. This is NOT a “traditional” genoa furling solution i.e. with an aluminium foil over the existing wire forestay, however, it is an increasingly popular, lightweight alternative for both offshore racing and cruising sailors alike. Traditional Genoa furler / foil system (©Facnor) We will be describing the key components, advantages and disadvantages of the system, discussing the appropriate use of wire vs composite fibre stays, setup methods and various sail interfaces and investigating the implications for the boat’s sail plan. Finally, we’ll be offering some guidance on correct specification. 2. What is a “Structural Furling Forestay”? a) Description The main forestay on a sailing yacht is a crucial part of its “standing rigging” i.e. primary mast support, without which the mast will fall down! It is a permanent installation, normally with a fixed length and an essential element for maintaining the correct rig tension and tune. -

Peat Database Results Hampshire

Baker's Rithe, Hampshire Record ID 29 Authors Year Allen, M. and Gardiner, J. 2000 Location description Deposit location SU 6926 1041 Deposit description Deposit stratigraphy Preserved timbers (oak and yew) on peat ledge. One oak stump in situ. Peat layer 0.15-0.26 m deep [thick?]. Associated artefacts Early work Sample method Depth of deposit 14C ages available -1 m OD Yes Notes 14C details ID 12 Laboratory code R-24993/2 Sample location Depth of sample Dated sample description [-1 m OD] Oak stump Age (uncal) Age (cal) Delta 13C 3735 ± 60 BP 2310-1950 cal. BC Notes Stump BB Bibliographic reference Allen, M. and Gardiner, J. 2000 'Our changing coast; a survey of the intertidal archaeology of Langstone Harbour, Hampshire', Hampshire CBA Research Report 12.4 Coastal peat resource database (Hazell, 2008) Page 1 of 86 Bury Farm (Bury Marshes), Hampshire Record ID 641 Authors Year Long, A., Scaife, R. and Edwards, R. 2000 Location description Deposit location SU 3820 1140 Deposit description Deposit stratigraphy Associated artefacts Early work Sample method Depth of deposit 14C ages available Yes Notes 14C details ID 491 Laboratory code Beta-93195 Sample location Depth of sample Dated sample description SU 3820 1140 -0.16 to -0.11 m OD Transgressive contact. Age (uncal) Age (cal) Delta 13C 3080 ± 60 BP 3394-3083 cal. BP Notes Dark brown humified peat with some turfa. Bibliographic reference Long, A., Scaife, R. and Edwards, R. 2000 'Stratigraphic architecture, relative sea-level, and models of estuary development in southern England: new data from Southampton Water' in ' and estuarine environments: sedimentology, geomorphology and geoarchaeology', (ed.s) Pye, K. -

Gazetteer.Doc Revised from 10/03/02

Save No. 91 Printed 10/03/02 10:33 AM Gazetteer.doc Revised From 10/03/02 Gazetteer compiled by E J Wiseman Abbots Ann SU 3243 Bighton Lane Watercress Beds SU 5933 Abbotstone Down SU 5836 Bishop's Dyke SU 3405 Acres Down SU 2709 Bishopstoke SU 4619 Alice Holt Forest SU 8042 Bishops Sutton Watercress Beds SU 6031 Allbrook SU 4521 Bisterne SU 1400 Allington Lane Gravel Pit SU 4717 Bitterne (Southampton) SU 4413 Alresford Watercress Beds SU 5833 Bitterne Park (Southampton) SU 4414 Alresford Pond SU 5933 Black Bush SU 2515 Amberwood Inclosure SU 2013 Blackbushe Airfield SU 8059 Amery Farm Estate (Alton) SU 7240 Black Dam (Basingstoke) SU 6552 Ampfield SU 4023 Black Gutter Bottom SU 2016 Andover Airfield SU 3245 Blackmoor SU 7733 Anton valley SU 3740 Blackmoor Golf Course SU 7734 Arlebury Lake SU 5732 Black Point (Hayling Island) SZ 7599 Ashlett Creek SU 4603 Blashford Lakes SU 1507 Ashlett Mill Pond SU 4603 Blendworth SU 7113 Ashley Farm (Stockbridge) SU 3730 Bordon SU 8035 Ashley Manor (Stockbridge) SU 3830 Bossington SU 3331 Ashley Walk SU 2014 Botley Wood SU 5410 Ashley Warren SU 4956 Bourley Reservoir SU 8250 Ashmansworth SU 4157 Boveridge SU 0714 Ashurst SU 3310 Braishfield SU 3725 Ash Vale Gravel Pit SU 8853 Brambridge SU 4622 Avington SU 5332 Bramley Camp SU 6559 Avon Castle SU 1303 Bramshaw Wood SU 2516 Avon Causeway SZ 1497 Bramshill (Warren Heath) SU 7759 Avon Tyrrell SZ 1499 Bramshill Common SU 7562 Backley Plain SU 2106 Bramshill Police College Lake SU 7560 Baddesley Common SU 3921 Bramshill Rubbish Tip SU 7561 Badnam Creek (River -

Nfnpa 303/19 New Forest National Park Authority

Nutrient Planning Committee NFNPA 303/19 17 September 2019 Nutrient neutrality and new development – update NFNPA 303/19 NEW FOREST NATIONAL PARK AUTHORITY PLANNING COMMITTEE – 17 SEPTEMBER 2019 NUTRIENT NEUTRALITY AND NEW DEVELOPMENT – UPDATE Report by: Steve Avery, Executive Director Strategy & Planning Summary: This report provides an update on the need for new development to achieve ‘nutrient neutrality’ in order to avoid potential adverse impacts on the internationally protected sites of the Solent. The report summarises the main issues that have been raised recently by Natural England with local planning authorities across the Solent coast; before setting out details of the package of measures which will form the basis for mitigation. The report also recommends that the Authority works with the Partnership for South Hampshire and other partners to development a comprehensive, long-term mitigation strategy for the Solent. Recommendation: Members approve the overall approach to identifying mitigation measures as set out in this report; and endorse the principle of working with the Partnership for South Hampshire to develop a comprehensive, long-term mitigation strategy for the Solent. 1. Introduction 1.1 This report outlines the main issues surrounding nitrates in the protected Solent habitats; the recent advice from Natural England on the matter; and the range of potential measures available to form an interim mitigation solution. 1.2 Under the Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulations (2017, as amended), the Authority is a ‘competent authority’ and must therefore undertake an ‘appropriate assessment’ of any planning decisions that are likely to have a significant effect on a European site. In the context of the Solent this includes the Solent & Southampton Water Special Protection Area and the Solent Maritime Special Area of Conservation. -

Local Produce Guide

FREE GUIDE AND MAP 2019 Local Produce Guide Celebrating 15 years of helping you to find, buy and enjoy top local produce and craft. Introducing the New Forest’s own registered tartan! The Sign of True Local Produce newforestmarque.co.uk Hampshire Fare ‘‘DON’T MISS THIS inspiring a love of local for 28 years FABULOUS SHOW’’ MW, Chandlers Ford. THREE 30th, 31st July & 1st DAYS ONLY August 2019 ''SOMETHING FOR THE ''MEMBERS AREA IS WHOLE FAMILY'' A JOY TO BE IN'' PA, Christchurch AB, Winchester Keep up to date and hear all about the latest foodie news, events and competitions Book your tickets now and see what you've been missing across the whole of the county. www.hampshirefare.co.uk newforestshow.co.uk welcome! ? from the New Forest Marque team Thank you for supporting ‘The Sign of True Local Produce’ – and picking up your copy of the 2019 New Forest Marque Local Produce Guide. This year sees us celebrate our 15th anniversary, a great achievement for all involved since 2004. Originally formed as ‘Forest Friendly Farming’ the New Forest Marque was created to support Commoners and New Forest smallholders. Over the last 15 years we have evolved to become a wide reaching ? organisation. We are now incredibly proud to represent three distinct areas of New Forest business; Food and Drink, Hospitality and Retail and Craft, Art, Trees and Education. All are inherently intertwined in supporting our beautiful forest ecosystem, preserving rural skills and traditions and vital to the maintenance of a vibrant rural economy. Our members include farmers, growers and producers whose food and drink is grown, reared or caught in the New Forest or brewed and baked using locally sourced ingredients. -

The Helmsman the Our Mission

United States Naval Academy Sailing Squadron Safety Magazine usna.edu/sailingusna.edu/sailing Spring 2015 The Helmsman Our mission: The United States Naval Academy Sailing United States Naval Academy Squadron directly contributes to the Naval Sailing Squadron Academy’s overall mission of developing future naval leaders. Naval Academy Commander Les Spanheimer Sailing meets this goal by providing Director of Naval Academy Sailing Midshipmen with hands-on leadership [email protected] (410) 293-5601 development through sailing. Naval Academy Sailing believes in not only promoting Lieutenant Commander Laurie Coffey Deputy Director of Naval Academy Sailing leadership development but also a culture of [email protected] safety. With this in mind, we believe that shar- (410) 293-5600 ing firsthand experiences that occur both on Mr. Jon Wright and off the water can lead to a higher aware- Vanderstar Chair, Naval Academy Sailing ness of sailing safety. [email protected] (410) 293-5606 Lieutenant Rob “Jobber” Bowman Special Thanks to the following people for Maintenance Officer, Naval Academy Sailing “The Helmsman” Editor and Publisher their article and photo contributions: [email protected] (410) 293-5634 Tim Queeney editor Ocean Navigator Mr. Frank Feeley Ben Spraque Richard Stevenson Commander Les Spanheimer, USN USNA Sailing website: usna.edu/sailing The Helmsman Page 2 Volume 2, Issue 1 The Helmsman Spring 2015 Naval Aviation has long enjoyed a free exchange Special points of interest: of lessons learned. That tradition permeates every post-flight debrief and is publicly revealed Weather in a bi-monthly Navy & Marine Corps Aviation Safety Magazine entitled “Approach.” Published Sailboat Maintenance by the Naval Safety Center, “Approach” is a col- lection of first-person narrative accounts of Na- val Aviation mishaps, close calls, and lessons Situational Awareness learned. -

Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation Sincs Hampshire.Pdf

Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation (SINCs) within Hampshire © Hampshire Biodiversity Information Centre No part of this documentHBIC may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recoding or otherwise without the prior permission of the Hampshire Biodiversity Information Centre Central Grid SINC Ref District SINC Name Ref. SINC Criteria Area (ha) BD0001 Basingstoke & Deane Straits Copse, St. Mary Bourne SU38905040 1A 2.14 BD0002 Basingstoke & Deane Lee's Wood SU39005080 1A 1.99 BD0003 Basingstoke & Deane Great Wallop Hill Copse SU39005200 1A/1B 21.07 BD0004 Basingstoke & Deane Hackwood Copse SU39504950 1A 11.74 BD0005 Basingstoke & Deane Stokehill Farm Down SU39605130 2A 4.02 BD0006 Basingstoke & Deane Juniper Rough SU39605289 2D 1.16 BD0007 Basingstoke & Deane Leafy Grove Copse SU39685080 1A 1.83 BD0008 Basingstoke & Deane Trinley Wood SU39804900 1A 6.58 BD0009 Basingstoke & Deane East Woodhay Down SU39806040 2A 29.57 BD0010 Basingstoke & Deane Ten Acre Brow (East) SU39965580 1A 0.55 BD0011 Basingstoke & Deane Berries Copse SU40106240 1A 2.93 BD0012 Basingstoke & Deane Sidley Wood North SU40305590 1A 3.63 BD0013 Basingstoke & Deane The Oaks Grassland SU40405920 2A 1.12 BD0014 Basingstoke & Deane Sidley Wood South SU40505520 1B 1.87 BD0015 Basingstoke & Deane West Of Codley Copse SU40505680 2D/6A 0.68 BD0016 Basingstoke & Deane Hitchen Copse SU40505850 1A 13.91 BD0017 Basingstoke & Deane Pilot Hill: Field To The South-East SU40505900 2A/6A 4.62 -

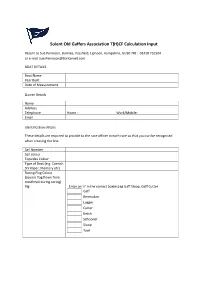

Solent Old Gaffers Association T(H)CF Calculation Input

Solent Old Gaffers Association T(H)CF Calculation Input Return to Sue Pennison, Burnlea, Passfield, Liphook, Hampshire, GU30 7RJ : 01428 751504 or e-mail [email protected] BOAT DETAILS Boat Name Year Built Date of Measurement Owner Details Name Address Telephone Home : Work/Mobile: Email Identification details These details are required to provide to the race officer in each race so that you can be recognised when crossing the line. Sail Number Sail colour Topsides Colour Type of Boat (e.g. Cornish Shrimper, Memory etc) Racing Flag Colour (square flag flown from masthead during racing) Rig Enter an ‘x’ in the correct box(es) eg Gaff Sloop, Gaff Cutter Gaff Bermudan Lugger Cutter Ketch Schooner Sloop Yawl BOAT CONSTRUCTION AND MEASUREMENTS BOAT CONSTRUCTION Type 1 Type 2 Type 3 Type 4 Hull shape (Select the closest shape from the four Type = above) Mark appropriate box with an ‘X’ If the boat has a Hinged Centreplate or daggerboard moveable keel for Lee boards boards enter ‘x’ in box Ballasted/drop keel – Weight of ballast = ________________ lbs/kg Indicate hull Carvel or clinker plank on frame, wood plank and wood/metal frame construction Metal or ferrocement Wood epoxy or GRP Composite foam, carbon or similar (describe below) Description : Indicate spar Timber contruction Aluminium Composite, carbon or similar (describe below) Description : MEASUREMENTS Indicate unit used with an ‘x’ Feet and inches Metres Hull LOA LWL Beam = = = Draught As measured (with plate up if applicable) Plate down if fitted = = Foretriangle I= J= Mainmast H= G= B= TH= TI= Mizzenmast H= G= B= TH= TI= Foremast H= G= B= TH= TI= Propeller None Fixed-2 bladed Fixed-3 bladed Folding-2 Folding-3 Mark with bladed bladed ‘x' NOTES ON HOW TO TAKE THE RIGHT MEASUREMENTS General Mainsails, mizzens and gaff foresails are measured on the sails. -

59 EDITORIAL. VOL. XVIII, Pt. 2, of the Proceedings Will Be Published In

PAPERS AND PROCEEDINGS " 59 EDITORIAL. OL. XVIII, Pt. 2, of the Proceedings will be published in July, 1953. It is hoped that this volume, which will include Vreviews of books received since 1950, notes of Field Meetings, and a list of those periodicals on the H.F.C. exchange list, will bring the Proceedings up to date, e.g., up to the end of 1952. Material intended for publication should be sent to the Hon. Editor, 10 The Close, Winchester. CORRESPONDENCE. THE STEAM PLOUGH IN HAMPSHIRE. Mr. Frank Warren writes concerning Mr. FusselFs article (Vol. XVII, p. 286) : " Richard Stratton of Broad Hinton, and Salthrop, Wiltshire (who lies buried in Winchester Cemetery), bought in 1859 the first Fowler steam plough for use on his farms. His son, James Stratton, came to farm Chilcombe, Winchester, in 1866 and introduced steam ploughing to Hampshire." CORRECTION. In the article on Hampshire Drawings in the Bodleian Library, Oxford, published in the Hampshire' Field Club Proceedings, Vol. XVII, page 139, the reference to the manuscript album should be " Western MSS. 17,507." PAPERS AND PROCEEDINGS 71 SUBJECT SECRETARIES' REPORTS. BIOLOGICAL SECTION. Weather 1951. " Deplorable" seems to be the only suitable adjective to describe the meteorological setting of the year 1951. Only once in the whole year, on July 2nd, did the temperature reach 80°, and on 18th, 20th and 28th of that month 79°. The highest shade temperatures in any other months were 75'5° on April 25th, 75° on September 6th, 74° on two days in June, the 5th and 21st, and on August 1st. -

Light Air Sails

Heavy Hitters for Light Air - 1 - Cruising Sails: Heavy Hitters for Light Air By Carol Hasse (Originally published in Cruising World Magazine, May 2005) Our joyously anticipated Galapagos Islands landfall wasn’t going well. In fact, it was getting really scary. After 17 magical days at sea we were being set by a powerful current at an alarming rate toward the outlying rocks of an equatorial island populated only by marine iguanas, flamingoes, and finches. The engine that had run hot, loud, and flawlessly one hour each day of our passage while charging batteries, refused to start and had no intention of rescuing us from imminent shipwreck. Our sturdy working sails—main, genoa, and staysail—hung limp in the calm. I pondered my options. Did we have time to launch the dinghy and tow Strider, our 37’ cutter, by the ash breeze? Would anyone, anywhere hear a Mayday? Should we prepare to abandon ship? Surely I was too young to die, wasn’t I? The skipper’s wife suddenly remembered the spinnaker that had been packed in the forepeak since their Pacific cruise began six months earlier. With the speed of an America’s Cup crew we set the chute, and slowly but steadily sailed clear of danger. That was my first profound and indelible lesson in the importance of light air sails. Usually large and often colorful, light air sails are made of thin strong fabric and are meant to move a vessel along in winds of Force 1 to 3. They might not spring to mind along with storm jibs and life rafts when one begins outfitting a boat for offshore cruising, but they can make a vital contribution to the safety, comfort, and speed of a voyage, not to mention its pure enjoyment. -

Garcia Exploration 45

Garcia Exploration 45 General Description - Standard version 2 Cabins / 2 Heads compartments / 1 sea bunk Garcia Exploration 45 - General description I. Key specification A boat designed to sail and live aboard both in high latitudes and tropical waters Integral aluminium centreboard Deck salon with 270° visibility and internal steering position Watertight companionway door Protected watch position in forward part of the cockpit, with forward view Watertight forward aluminium bulkhead Watertight aft aluminium bulkhead with watertight hatches to access the stern compartments from the aft cabins All through-hull fittings made of welded aluminium - all valves positioned above waterline Double glazed salon windows, one opening above the galley - coachroof extends beyond the windows to act as a sun-awning Thermal and acoustic insulation above waterline using automotive-grade polyethylene foam panels Insulated floor (thick foam core) Chain locker centrally positioned at the foot of the mast – electric windlass located in locker below deck just forward of the mast Centrally located large capacity tanks - water and fuel tanks can be ballasted port/starboard Centrally located service battery set Generous stowage space available throughout the boat Forefoot chainplate for towing and ice breaking Integrated aft arch for electronics, wind generator, solar panels and use as davits Double steering system, twin aluminium rudder configuration JEFA self-aligning bearings to ensure optimal control in heavy seas, protective skegs and sacrificial end-fitting Large aft platform with easy access to/from the water Life raft stowage in locker accessed from aft platform All essential lines controlled from the cockpit Sept2018 V4.4 Page 2 of 25 Non-contractual document Garcia Exploration 45 - General description II. -

HH Catamarans HH55 Catamaran

http://www.morrellimelvin.com Morrelli & Melvin Yacht Sales Toll-free: 877-637-0760 201 Shipyard Way, Suite B Tel: (949) 500-3440 Newport Beach, CA 92663, United States [email protected] HH Catamarans HH55 Catamaran • Year: 2018 • Location: United States • Hull Material: Composite • Fuel Type: Diesel • YachtWorld ID: 2792603 HH55 • Condition: New The HH55 – Winner of the 2017 Boat of the Year, in the Cruising Catamaran category. Designed for a couple to handle, the HH55 sets the standard for performance luxury sailing. With its Morrelli & Melvin design pedigree, its generous interior spaces, and clever use of ultra-modern materials, the HH55 achieves a level of performance and luxury, not previously found in this genre of very fast, cruising catamarans Performance is the backbone of this design. Available in two configurations (forward cockpit/center steering, or dual aft steering) - the HH55 is designed primarily for a couple to sail, in comfort, style and safety. However, this vessel is able to ‘kick it up a notch’ and move with speed ,when desired. Modern hull forms, the latest generation curved C daggerboards, and “T” rudders, incorporate design learnings from the latest America’s Cup campaigns. 100% carbon fiber composite sandwich construction, produces hulls and structures of incredible strength and stiffness, while interior construction of lightweight cored panels, finished with exquisite veneers, present you with the highest quality interior finishes. Not a “cookie-cutter” high production vessel; the HH55 is offered with numerous interior and exterior layout options, allowing for customization to meet the individualized needs of the most discerning clients. Unique styling, innovative sailing systems, beautiful interiors, and your personal input, combine to make each HH55 a truly exceptional yacht.