Are Protected Areas Required to Maintain Functional Diversity in Human-Modified Landscapes?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bhutan Birding the Buddhist Kingdom II & Assam Extension 8Th April to 1St May 2018 (25 Days) Trip Report

Bhutan Birding the Buddhist Kingdom II & Assam Extension 8th April to 1st May 2018 (25 Days) Trip Report Beautiful Nuthatch by David Erterius Trip report compiled by Tour Leaders: David Erterius & Greg de Klerk Rockjumper Birding Tours View more tours to Bhutan Trip Report – RBL Bhutan - Birding the Buddhist Kingdom II & Assam Ext 2018 2 Tour Summary There can hardly be a greater contrast on a birding tour than this tour through Assam and the Buddhist kingdom of Bhutan! We began our tour with an impromptu birding session in the hotel gardens, where we located Yellow-footed Green Pigeon, Indian Cuckoo, Blue-tailed Bee-eater, Coppersmith Barbet, Striated Swallow, Dusky Warbler, Striated Grassbird, Zitting Cisticola, Common Tailorbird and Oriental Magpie-Robin before navigating through the bustling Indian city of Guwahati. Our next stop was a regional waste dump. It is here, among the swathes of trash – which had been fermenting due to the pre-monsoon rains – that we connected with the critically endangered Greater Adjutant. Fittingly, these large grotesque stalks were found scavenging between heaps of waste being moved by excavators in close proximity to the main entrance. We then had the leisure of exploring the surrounding area, which yielded Lesser Whistling Duck, Garganey, Glossy Ibis, Grey-headed Swamphen, Black-winged Stilt, Whiskered Tern, Great Myna, Rosy Pipit, and Citrine and White Wagtails. After our visit to the rolling panoramas of the landfill site, we traversed many kilometres of cultivation and villages – dotted with occasional Black-winged Kite – as we made our way to Nameri. After a quick break in Tezpur, we made the final stretch of the journey to Nameri, collecting Grey-breasted Prinia en route, where we stopped for lunch in the company of a couple of Common Blue-tailed Bee-eater by Keith Hill Mynas. -

Thailand Highlights 14Th to 26Th November 2019 (13 Days)

Thailand Highlights 14th to 26th November 2019 (13 days) Trip Report Siamese Fireback by Forrest Rowland Trip report compiled by Tour Leader: Forrest Rowland Trip Report – RBL Thailand - Highlights 2019 2 Tour Summary Thailand has been known as a top tourist destination for quite some time. Foreigners and Ex-pats flock there for the beautiful scenery, great infrastructure, and delicious cuisine among other cultural aspects. For birders, it has recently caught up to big names like Borneo and Malaysia, in terms of respect for the avian delights it holds for visitors. Our twelve-day Highlights Tour to Thailand set out to sample a bit of the best of every major habitat type in the country, with a slight focus on the lush montane forests that hold most of the country’s specialty bird species. The tour began in Bangkok, a bustling metropolis of winding narrow roads, flyovers, towering apartment buildings, and seemingly endless people. Despite the density and throng of humanity, many of the participants on the tour were able to enjoy a Crested Goshawk flight by Forrest Rowland lovely day’s visit to the Grand Palace and historic center of Bangkok, including a fun boat ride passing by several temples. A few early arrivals also had time to bird some of the urban park settings, even picking up a species or two we did not see on the Main Tour. For most, the tour began in earnest on November 15th, with our day tour of the salt pans, mudflats, wetlands, and mangroves of the famed Pak Thale Shore bird Project, and Laem Phak Bia mangroves. -

Avifaunal Diversity of Bibhutibhushan Wildlife Sanctuary, West Bengal, India

Available online at www.worldscientificnews.com WSN 71 (2017) 150-167 EISSN 2392-2192 Avifaunal Diversity of Bibhutibhushan Wildlife Sanctuary, West Bengal, India Shiladitya Mukhopadhyay1,* and Subhendu Mazumdar2 1Post Graduate Department of Zoology, Barasat Government College, North 24 Parganas, India 2Department of Zoology, Shibpur Dinobundhoo Institution (College), Shibpur, Howrah, India *E-mail address: [email protected] ABSTRACT Birds are found in a variety of habitats, performing various functions. They are highly sensitive to even minor perturbation in ecosystems. Documentation of avian assemblages in different ecosystems is, therefore, becoming increasingly important from environmental monitoring perspective. In absence of comprehensive account of birds of Bibhutibhushan Wildlife Sanctuary, West Bengal, India, we made an attempt to document the birds thriving in this protected area. A total of 102 species of birds belonging to 13 orders and 46 families were recorded during the study period (June 2013 – May 2016). Maximum number of species belong to the order Passeriformes (49 species) and minimum under order Anseriformes (1 species). Among the total bird species, 83 species (81.37%) were resident, 15 species (14.71%) were winter visitor, three species (2.94%) were summer visitor and one species (0.98%) was passage migrant. We noted 38 species of birds (including 36 residents and two summer visitors) to breed within the sanctuary. Analysis of feeding guild data revealed that 46.08% were insectivore, 22.55% were carnivore, 15.69% were omnivore, 6.86% were granivore, 5.88% were frugivore, 1.96% were nectarivore and 0.98% were herbivore. Grey-headed Fish Eagle (Icthyophaga ichthyaetus) and Red- breasted Parakeet (Psittacula alexandri) are two Near Threatened (NT) species designated by IUCN. -

K Here for the Full Trip Report

Capped Langur , Small Pratincole , WhiteWhite----wingedwinged Ducks , Gaur , Sultan Tit , Great Hornbill andand Pied Falconet ; Nameri Here a couple of ducks had now turned up , and while we were watching them , a Gaur suddenly came out of the forest for a drink and some fresh grass from the meadow surrounding the lake. We also saw several Wild Boars and a small group of Northern Red Muntjacs here , not to mention a Great Hornbill , Sultan Tits and a small party of Scarlet Minivets. No doubt this was a fantastic place , and there is no telling what could have been seen if more time had been spent here. Back in the camp we enjoyed yet another good meal , before driving a bit up river where this afternoons boat ride was to begin. We didn’t really see all that many birds while rafting on the river , but even so it was a nice experience to watch the beautiful landscape pass by in a leisurely pace – not exactly white water rafting this! Of course , there were a few avian highlights as well , including lots of Small Pratincoles , a couple of Crested Kingfisher and some nice River Lapwings , but we somehow managed to dip out on Ibisbill. We walked back to the camp as the sun was setting , but didn’t add anything new to our list , though a couple of Brown Hawk Owls put on quite a show for Erling , who was the first one to get back. We tried again with some spotlighting in the evening , and heard a calling Oriental Scops Owl not to far from the road but still impossible to see. -

Malaysia & Borneo Trip Report

Malaysia & Borneo Trip Report Rainforest Birds & Mammals th th 8 to 26 June 2015 The scarce and beautiful Jambu Fruit Dove, Taman Nagara by Rosemary Loyd RBT Trip Report Malaysia & Borneo 2015 2 The rare Whitehead’s Trogon, Mt Kinabalu and a male Crested Fireback, Taman Nagara, both by Butch Carter Top Ten Birds as voted by the participants: 1) Whitehead’s Broadbill 2) Whitehead’s Trogon 3) Jambu Fruit Dove 4) Bornean Green Magpie 5) Long-tailed Broadbill 6) Buffy Fish Owl 7) Oriental Dwarf Kingfisher/Hooded Pitta 8) Temminck’s Sunbird 9) Rhinoceros Hornbill 10) Crested Fireback Mammals: 1) Malaysian Tapir 2) Orangutan 3) Proboscis Monkey 4) Small-clawed Otter RBT Trip Report Malaysia & Borneo 2015 3 Tour Leaders: Dennis Yong and Erik Forsyth Tour report compiled by Tour Leader: Erik Forsyth Temminck’s Sunbird by John Clark Tour Summary On this year’s tour we recorded the rare and highly prized Whitehead’s Trogon, Whitehead’s Broadbill (after a long search on Mount Kinabalu) and Garnet, Blue-headed, Black-crowned and Hooded Pittas. Other mouthwatering species seen were Rhinoceros, Wreathed, Wrinkled and Black Hornbills, White- fronted and Black-thighed Falconets, Black-and-red, Black-and-yellow, Long-tailed, Dusky, Green and Banded Broadbills, the stunning Oriental Dwarf, Blue-eared, Blue-banded and Stork-billed Kingfishers, Red-headed, Diard’s, Red-naped and Scarlet-rumped Trogons, Great-billed Heron, Painted and Storm’s Storks, Lesser Adjutant, Wallace’s, Rufous-bellied and Blyth’s Hawk-Eagles, Crested Fireback, Buffy Fish and Brown Wood Owls, the highly sought-after Bornean Bristlehead and Blue Nuthatch, the endangered Straw-headed Bulbul, a whopping eight sightings of Orangutan and several troops of Proboscis Monkey, Malaysian Tapir and Western Tarsier. -

Thailand Custom Tour 29 January -13 February, 2017

Tropical Birding Trip Report THAILAND JANUARY-FEBRUARY, 2017 Thailand custom tour 29 January -13 February, 2017 TOUR LEADER: Charley Hesse Report by Charley Hesse. Photos by Charley Hesse & Laurie Ross. All photos were taken on this tour When it comes to vacation destinations, Thailand has it all: great lodgings, delicious food, scenery, good roads, safety, value for money and friendly people. In addition to both its quantity & quality of birds, it is also one of the most rapidly evolving destinations for bird photography. There are of course perennial favourite locations that always produce quality birds, but year on year, Thailand comes up with more and more fantastic sites for bird photography. On this custom tour, we followed the tried and tested set departure itinerary and found an impressive 420 species of birds and 16 species of mammals. Some of the highlights included: Spoon-billed Sandpiper and Nordmann’s Greenshank around Pak Thale; Wreathed Hornbill, Long-tailed & Banded Broadbills inside Kaeng Krachan National Park; Rosy, Daurian & Spot-winged Starlings at a roost site just outside; Kalij Pheasant, Scaly-breasted & Bar-backed Partridges at a private photography blind nearby; Siamese Fireback and Great Hornbill plus Asian Elephant & Malayan Porcupine at Khao Yai National Park; countless water birds at Bueng Boraphet; a myriad of montane birds at Doi Inthanon; Giant Nuthatch at Doi Chiang Dao; Scarlet-faced Liocichla at Doi Ang Khang; Hume’s Pheasant & Spot-breasted Parrotbill at Doi Lang; Yellow-breasted Buntings at Baan Thaton; and Baikal Bush-Warbler & Ferruginous Duck at Chiang Saen. It was a truly unforgettable trip. www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Tropical Birding Trip Report THAILAND JANUARY-FEBRUARY, 2017 29th January – Bangkok to Laem Pak Bia After a morning arrival in Bangkok, we left the sprawling metropolis on the overhead highways, and soon had our first birding stop at the Khok Kham area of Samut Sakhon, the neighbouring city to Bangkok. -

Assam Extension I 17Th to 21St March 2015 (5 Days)

Trip Report Assam Extension I 17th to 21st March 2015 (5 days) Greater Adjutant by Glen Valentine Tour leaders: Glen Valentine & Wayne Jones Trip report compiled by Glen Valentine Trip Report - RBT Assam Extension I 2015 2 Top 5 Birds for the Assam Extension as voted by tour participants: 1. Pied Falconet 4. Ibisbill 2. Greater Adjutant 5. Wedge-tailed Green Pigeon 3. White-winged Duck Honourable mentions: Slender-billed Vulture, Swamp Francolin & Slender-billed Babbler Tour Summary: Our adventure through the north-east Indian subcontinent began in the bustling city of Guwahati, the capital of Assam province in north-east India. We kicked off our birding with a short but extremely productive visit to the sprawling dump at the edge of town. Along the way we stopped for eye-catching, introductory species such as Coppersmith Barbet, Purple Sunbird and Striated Grassbird that showed well in the scopes, before arriving at the dump where large frolicking flocks of the endangered and range-restricted Greater Adjutant greeted us, along with hordes of Black Kites and Eastern Cattle Egrets. Eastern Jungle Crows were also in attendance as were White Indian One-horned Rhinoceros and Citrine Wagtails, Pied and Jungle Mynas and Brown Shrike. A Yellow Bittern that eventually showed very well in a small pond adjacent to the dump was a delightful bonus, while a short stroll deeper into the refuse yielded the last remaining target species in the form of good numbers of Lesser Adjutant. After our intimate experience with the sought- after adjutant storks it was time to continue our journey to the grassy plains, wetlands, forests and woodlands of the fabulous Kaziranga National Park, our destination for the next two nights. -

NHBSS 046 1J Meckvichai Ne

NAT. HIST. BULL. SIAM Soc. 46: 55 --6 2, 1998 NEST CHARACTERISTICS OF COPPERSMITH BARBETS (MEGALAIMA HAEMACEPHALA INDICA ,LATHAM , 1790) Wina Meckvichai 1 ABSTRACT ppersmith C'O ppersmith Barbets are 町opical treet 'O p dweIIers which live in decidu 'O us f'O rests ,gardens 'O r even in t 'O wns. On 出e Chulal 'O ngk 'O m University carnpus ,they actively breed in 出e dry seas 'O n during January-March. B 'O th the males and fem aI es excavate dead and dry branches 'O f Samanea saman , Delonix regia ,Terminalia catappa ,Pel 加tω ,op 凶horu 官 mpteroc ω'arpum , 叫n叫,Pa~成出kμiωas伊pe, 釘Cαt回旧叫s叫a仏, 争S'pa ωth 加odea 叩cam叩lfJ加 an 叩z Each Each yea 釘r 血ey excavat 巴 several new h'O les but '0凶 y 'O n巴 h'O le 鴎serveωs 悩as 白巴 nes “t. The 'O thers are are used as spare nests and ro 'O sting h'O les. Th e entrances 'O f出eh 'O les 釘 e nearly circular ,3.2- 4.8 4.8 cm di in 制 neter ,are always 'O n 出eundersides 'O f sl 'O ping branches ,and aII 'O w 'O nly 'O ne bird t 'O enter at a time. The h 'O les are excavated t 'O f'O rm as 'O ck-shaped chamber 5.5 --6 .9 cm wide and 14.2 ← 26.0 cm deep. Th e preferred nest branches are 21.6-4 6.5 cm in circumference ,2-241 kg/cm 2 in hardness ,and c'O ntain 9.75-12 .4 1% m 'O isture. -

DIVERSITY of BIRDS ACROSS LAND USE and HABITAT GRADIENTS in FORESTS, RUBBER AGROFORESTS and RUBBER PLANTATIONS of NORTH SUMATRA Asep Ayat1,* and Hesti L

Indonesian Journal of Forestry Research Vol. 2, No. 2, October 2015, 103-120 ISSN: 2355-7079 / E-ISSN: 2406-8195 DIVERSITY OF BIRDS ACROSS LAND USE AND HABITAT GRADIENTS IN FORESTS, RUBBER AGROFORESTS AND RUBBER PLANTATIONS OF NORTH SUMATRA Asep Ayat1,* and Hesti L. Tata2 1Burung Indonesia, Jalan Dadali 32, Bogor 16161, Indonesia 2Forest Research and Development Center, Jl. Gunung Batu 5, Bogor, Indonesia Received: 31 March 2014, Revised: 10 May 2014, Accepted: 11 October 2015 DIVERSITY OF BIRDS ACROSS LAND USE AND HABITAT GRADIENTS IN FORESTS, RUBBER AGROFORESTS AND RUBBER PLANTATIONS OF NORTH SUMATRA. Birds play a pivotal role in the ecosystem, but in disturbed areas their roles may be limited due to the changes of their natural habitats. This paper studies the birds' habitats in Simalungun and Asahan Districts, North Sumatra. The study was conducted in four habitats: natural forest, rubber agroforests, rubber monoculture plantations and emplacement areas. The birds were observed using descriptive survey methods by implementing a quick biodiversity survey, data were collected along one km transect. The results showed that in total, 142 species of birds from 42 families were observed in the four habitats. Natural forests had the highest diversity of bird species, followed by rubber agroforests, emplacement areas and rubber plantations, with a Shannon-Wiener index of 3.8, 3.6, 3.0 and 2.9, respectively. Regarding the IUCN red list species, 12 bird species of near- threatened status and 2 species of vulnerable status were recorded. Based on CITES categories, one species was listed in the Appendix I, 12 species were classified in Appendix II and 26 bird species were protected under Indonesian regulations. -

Avifauna of Chandrampalli Dam, Chincholi, Gulbarga District Karnataka

IMPACT: International Journal of Research in Applied, Natural and Social Sciences (IMPACT: IJRANSS) ISSN(E): 2321-8851; ISSN(P): 2347-4580 Vol. 2, Issue 4, Apr 2014, 1-10 © Impact Journals AVIFAUNA OF CHANDRAMPALLI DAM, CHINCHOLI, GULBARGA DISTRICT KARNATAKA MANJUNATH & BHASKAR N JOSHI Department of Zoology, Gulbarga University, Gulbarga, Karnataka, India ABSTRACT The study involves avifauna of Chandrampalli dam (Chincholi taluk, Gulbarga district). The objective of the study included evaluate of species composition, relative abundance and distribution of avifauna of the chosen area. Line and point transect technique method were used for the survey purpose. A total of 51 species of birds belonging to 11 orders and 26 families were recorded. The Species consisting 34 resident, 8 winter and summer migrants were identified. Among the birds recorded in this study, 25 species were insectivorus, 9 omnivorus, 6 piscivorous, 2 carnivorus, 10 frugivorus, and 8 grainivorus. KEYWORDS: Avifauna, Chandrampalli Dam, Gulbarga INTRODUCTION Biodiversity at present is better understood for birds in many respects than any other major group of organisms because they probably inspire more extreme interest in humans, are often spectacular, relatively easily observed and not too cryptic to identify. Avifauna is one of the most important ecological indicators to evaluate the quality of habitats. Most of the birds are useful to mankind. Birds play a useful role in the control of insect of pests of agricultural crops, as predators of rodents, as scavengers, as seed dispensers and as pollinating agents. Therefore birds are reared not only for preserving ecological balance but also for products of economic importance such as downs feather. -

NESTING BEHAVIOUR of the COPPERSMITH BARBET - a Brief Study Project Overview

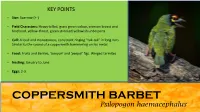

KEY POINTS • Size: Sparrow (+-) • Field Characters: Heavy-billed, grass green colour, crimson breast and forehead, yellow-throat, green streaked yellowish underparts • Call: A loud and monotonous, consistent ringing “tuk-tuk” in long runs. Similar to the sound of a coppersmith hammering on his metal • Food: Fruits and Berries, ‘banyan’ and ‘peepal’ figs. Winged termites • Nesting: January to June • Eggs: 2-3 COPPERSMITH BARBET Psilopogon haemacephalus NESTING BEHAVIOUR OF THE COPPERSMITH BARBET - A Brief Study Project Overview Details • Species: Coppersmith Barbet • Location: Pune, Maharashtra • Duration: March to April • Observation timings: Early mornings and late afternoons • Records: Observations on daily basis. Records done every week • Equipment Used: Nikon D5600 & Tamron 150-600mm + Tripod Observations • Week 1: The Barbet chick has a dull plumage and a whitish throat. The male and female do the feeding part simultaneously (Most of the times female). Beak is not developed. • Week 2: The chick has developed brighter colours than before and voluntarily gives a call to its parents for food. Breast spots have developed. Sex differentiation not possible yet. • Week 3: The chick’s beak is sharper and the instinct to peck is more rigorous. Incidents like pecking the parents’ stomach, pulling off feathers can be seen more often. Voluntarily calls for food. OBSERVATIONS • Week 4: The chick has developed a faint whitish cap on its head. Will develop red colour after maturity. Still not sure of the gender. No more calls to its parents. No indication of flight training yet. • Week 5: Colours have developed faintly. Not able to distinguish the sex. Peeps out of the hole and tries to come out and hang on the branch. -

Caged in the City: an Inventory of Birds for Sale in Ha Noi and Ho Chi Minh City, Viet Nam 1 TRAFFIC REPORT

TRAFFIC CAGED IN THE CITY: REPORT An inventory of birds for sale in Ha Noi and Ho Chi Minh City, Viet Nam SEPTEMBER 2017 James A. Eaton, Minh D. T. Nguyen, Madelon Willemsen, Jessica Lee and Serene C. L. Chng TRAFFIC Report: Caged in the city: An inventory of birds for sale in Ha Noi and Ho Chi Minh City, Viet Nam 1 TRAFFIC REPORT TRAFFIC, the wild life trade monitoring net work, is the leading non-governmental organization working globally on trade in wild animals and plants in the context of both biodiversity conservation and sustainable development. TRAFFIC is a strategic alliance of WWF and IUCN. Reprod uction of material appearing in this report requires written permission from the publisher. The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of TRAFFIC or its supporting organizations con cern ing the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views of the authors expressed in this publication are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect those of TRAFFIC, WWF or IUCN. Published by TRAFFIC. Southeast Asia Regional Office Suite 12A-01, Level 12A, Tower 1, Wisma AmFirst, Jalan Stadium SS 7/15, 47301 Kelana Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia Telephone : (603) 7880 3940 Fax : (603) 7882 0171 Copyright of material published in this report is vested in TRAFFIC. © TRAFFIC 2017. ISBN no: 928-983-3393-74-9 UK Registered Charity No.