40 and 40A High Street, Brentford, London

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A World Flora Online by 2020: a Discussion Document on Plans for the Achievement of Target 1 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation by 2020

CBD Distr. GENERAL UNEP/CBD/SBSTTA/16/INF/38 23 April 2012 ENGLISH ONLY SUBSIDIARY BODY ON SCIENTIFIC, TECHNICAL AND TECHNOLOGICAL ADVICE Sixteenth meeting Montreal, 30 April-5 May 2012 Item 8 of the provisional agenda* GLOBAL STRATEGY FOR PLANT CONSERVATION: WORLD FLORA ONLINE BY 2020 Note by the Executive Secretary 1. In decision X/17 the Conference of the Parties adopted the consolidated update of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation (GSPC) 2011-2020, with sixteen updated global targets for plant conservation, including Target 1 of developing, by 2020, an online Flora of all known plants. 2. This document provides a report for information to the participants of sixteenth meeting of the Subsidiary Body on Scientific, Technical and Technological Advice on steps taken to develop a ―World Flora online‖, its relevance for the implementation of the Convention and for the achievement of the other targets of the GSPC. 3. The document, prepared jointly by the Missouri Botanical Garden, the New York Botanical Garden, the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, and the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, is presented in the form and language in which it was received by the Secretariat. * UNEP/CBD/SBSTTA/16/1. I order to minimize the environmental impacts of the Secretariat’s processes, and to contribute to the Secretary-General’s initiative for a C-Neutral UN, this document is printed in limited numbers. Delegates are kindly requested to bring their copies to meetings and not to request additional copies. UNEP/CBD/SBSTTA/16/INF/38 Page 2 A World Flora Online by 2020: a discussion document on plans for the achievement of Target 1 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation by 2020 Presented to the Sixteenth meeting of the Subsidiary Body on Scientific, Technical and Technological Advice of the Convention on Biological Diversity, Montreal, 30 April – 5 May 2012. -

Acton and Chiswick Circular Trail (ACCT) – 6.5 Miles

Acton and Chiswick Circular Trail (ACCT) – 6.5 miles Acton Town Station – Gunnersbury Park – Strand on the Green – Gunnersbury Station – Chiswick business park - Gunnersbury Triangle Wildlife Reserve – Chiswick Park Station – Acton Green Common – Chiswick Common – Turnham Green Station – Bedford Park garden suburb - Acton Park – Churchfield Road – Crown Street - Mill Hill Road – Acton Town Station Route: Easy – mostly surfaced paths through parks and commons and quiet roads with short sections of main roads. Local Amenities: cafes, pubs, shops at several places. Toilets available at Gunnersbury Park and in some cafes/pubs and an Acton supermarket on route. Bike racks by Acton Town station and shops. Points of Interest: Gunnersbury Park – historic house, museum and park; the new Brentford Football Stadium; Strand on the Green on the Thames with historic houses; the landscaped Chiswick Business Park; London Wildlife Trust’s reserve at Gunnersbury; the garden suburb of Bedford Park; and Acton Park. Transport: Acton Town Station (Piccadilly and District) and local buses. Join or drop out at Kew Bridge rail station or Gunnersbury, Chiswick Park or Turnham Green tube stations. Starting at Acton Town Station. Turn left out of the station and walk past cafes and shops to cross the busy North Circular Road (A406) at lights. Continue ahead on Popes Lane to turn left into Gunnersbury Park (1), walk down the drive and turn 2nd right by a children’s playground, the café & toilets. Before the boating lake, turn left down a path by the side of the house to the Orangery. At the Orangery turn left to walk round the far side of the Horseshoe Lake. -

Buses from Brentford Station (Griffin Park)

Buses from Buses Brentford from Brentford Station Station (Griffin (Grif fiPark)n Park) 195 Charville Lane Estate D A O Business R W NE Park I R Bury Avenue N OU D TB M AS School IL E L AY GREAT WEST Charville W R QUARTE R Library O T D O D R M - K 4 RD YOR TON ROA RD M O R LAY RF Lansbury Drive BU for Grange Park and The Pine Medical Centre O D A OA E R A D D EW L R N I N Uxbridge County Court Brentford FC G B EY WEST R TL T R Griffin Park NE B Brentford TON RD D O OS IL O R OAD T AM O R A R GREA O H K N D MA D Church Road 4 M A R A A RO O RAE for Botanic Gardens, Grassy Meadow and Barra Hall Park NO EN A B R LIFD D R C SOU OA TH D Library Hayes Botwell Green Sports & Leisure Centre School © Crown copyright and database rights 2018 Ordnance Survey 100035971/015 Station Road Clayton Road for Hayes Town Medical Centre Destination finder Hayes & Harlington Destination Bus routes Bus stops Destination Bus routes Bus stops B K North Hyde Road Boston Manor 195 E8 ,sj ,sk ,sy Kew Bridge R 65 N65 ,ba ,bc Boston Manor Road 195 E8 ,sj ,sk ,sy Kew Road for Kew Gardens 65 N65 ,ba ,bc for Boston Manor Park Kingston R 65 N65 ,ba ,bc Boston Road for Elthorne Park 195 E8 ,sj ,sk ,sy Kingston Brook Street 65 N65 ,ba ,bc Bulls Bridge Brentford Commerce Road E2 ,sc ,sd Kingston Cromwell Road Bus Station 65 N65 ,ba ,bc Tesco Brentford County Court 195 ,sm ,sn ,sz Kingston Eden Street 65 N65 ,ba ,bc ,bc ,by 235 L Brentford Half Acre 195 E8 ,sm ,sn ,sz Western Road Lansbury Drive for Grange Park and 195 ,sj ,sk ,sy E2 ,sc ,sd The Pine -

Kew Bridge Conservation Area Is Small but Distinct

KEW BRIDGE Boundary: Map 27, note that this post-dates the UDP and UDP map Date of Designation: 1st June 2004 Date of Extension: Additional protection to the area: Listed grade l status of Pumping station; other listed buildings; partially in Thames Policy Area and Nature conservation area; partially in buffer zone of Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew: World Heritage Site. Special Architectural and/or Historic Interest The conservation area is based upon the topography and confluence of historic routes at the junction of the Thames crossing point: and their effect; also those of industrial uses of the area, and its workers, on the built environment, in particular the buildings now occupied by the Kew Bridge Steam Museum. The special architectural and historic interest of the area lies in the industrial character created by the pumping station and its associations, and the high quality of architectural style achieved for them: because of their importance and their location. The Bridge itself is important as an architectural landmark. The conservation area is partially residential in character and also displays a degree of commerce, business and industry that grew up in the area. The scale of these, including the fine station building, is small, and immediately adjacent buildings to the conservation area have a retro style. Two large commercial buildings of the middle twentieth century, nearby, which have been over clad and modified to become residential, are outside the conservation area. The pumping station is the dominating building within the area. It was designed by William Anderson, for the Grand Junction Waterworks Company, to extract river water from the Thames. -

Open a PDF List of This Collection

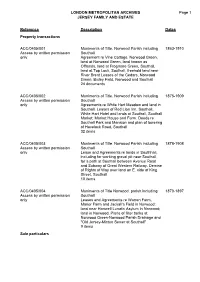

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 JERSEY FAMILY AND ESTATE ACC/0405 Reference Description Dates Property transactions ACC/0405/001 Muniments of Title. Norwood Parish including 1863-1910 Access by written permission Southall only Agreement re Vine Cottage, Norwood Green, land at Norwood Green, land known as Offlands, land at Frogmore Green, Southall, land at Top Lock, Southall, freehold land near River Brent Leases of the Cedars, Norwood Green, Bixley Field, Norwood and Southall 24 documents ACC/0405/002 Muniments of Title. Norwood Parish including 1875-1909 Access by written permission Southall only Agreements re White Hart Meadow and land in Southall. Leases of Red Lion Inn, Southall, White Hart Hotel and lands at Southall, Southall Market, Market House and Farm. Deeds re Southall Park and Mansion and plan of lowering of Havelock Road, Southall 32 items ACC/0405/003 Muniments of Title. Norwood Parish including 1878-1908 Access by written permission Southall only Lease and Agreements re lands in Southhall, including for working gravel pit near Southall, for a path at Southall between Avenue Road and Subway of Great Western Railway. Demise of Rights of Way over land on E. side of King Street, Southall 10 items ACC/0405/004 Muniments of Title Norwood. parish including 1870-1897 Access by written permission Southall only Leases and Agreements re Warren Farm, Manor Farm and Jackall's Field in Norwood; land near Hanwell Lunatic Asylum in Norwood; land in Norwood. Plans of filter tanks at Norwood Green-Norwood Parish Drainage and "Old Jersey-Minton Sewer at Southall" 9 items Sale particulars LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 2 JERSEY FAMILY AND ESTATE ACC/0405 Reference Description Dates ACC/0405/005 Muniments of Title Norwood Parish including 1903-1930 Access by written permission Southall only Sales Particulars - including properties in Southall, Norwood Green, Lampton, Osterley and Hanwell. -

THE CHARACTER of the LANDSCAPE 2.39 the Thames

THE CHARACTER OF THE LANDSCAPE 2.39 The Thames enters the Greater London Area at Hampton. From Hampton to Erith, the river fl ows through the metropolis; an urban area even though much of the riverside is verdant open space, particularly in the fi rst stretch between Hampton and Kew. 2.40 The character of the river is wonderfully varied and this chapter concentrates on understanding how that variety works. We have deliberately avoided detailed uniform design guidelines, such as standard building setbacks from the water’s edge. At this level, such guidelines would tend to stifl e rather than encourage the variety in character. Instead we have tried to highlight the main factors which determine the landscape character and propose recommendations to conserve and enhance it. 2.41 Landscape Character Guidance LC 1: New development and new initiatives within the Strategy area should be judged against the paramount aim of conserving and enhancing the unique character of the Thames Landscape as defi ned in the Strategy. The River 2.42 Although, being a physical boundary, the river is often on the periphery of county and local authority jurisdictions, it is essentially the centre of the landscape. The Thames has carved the terraces and banks that line its course, the valley sides drain down to its edges and the water acts as the main visual and physical focus. It is a dynamic force, constantly changing with the tide and refl ecting the wind and the weather on its surface. 2.43 Downstream of the great expanse of water at the confl uence with the Wey, the Thames fl ows from west to east – the Desborough Cut by-passing the large meander near Shepperton. -

Our Feltham Rediscovering the Identity of a Post-Industrial Town

London Borough of Hounslow ৷ Feltham ৷ 2019 Our Feltham Rediscovering the Identity of a Post-Industrial Town An Interactive Qualifying Project Report submitted to the Faculty of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science by: Meredith Forcier ৷ BME ৷ ‘20 Hannah Mikkila ৷ ME ৷ ‘20 Kyle Reese ৷ RBE/CS ৷ ‘20 Jonathan Sanchez ৷ ME/RBE ৷ ‘20 Nicholas Wotton ৷ MA ৷ ‘20 Advisors: Professor Fabio Carrera & Professor Esther Boucher-Yip https://sites.google.com/view/lo19-of/home [email protected] | [email protected] This report represents the work of WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of completion of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its website without editorial or peer review. For more information about the projects program at WPI, please see http://www.wpi.edu/academics/ugradstudies/project-learning.html Abstract The London Borough of Hounslow is implementing a fifteen-year revitalization plan for Feltham. Through interviews and community engagement, our project highlighted the elements that make up the identity of the town to be incorporated in the next steps in the redesign of the town center. The team created a website that incorporates project deliverables, a comprehensive list of bibliographical sources, an Encyclopedia of important town assets, a walking tour of key elements of town identity, and a promotional video. ii Acknowledgments There were many people who made the completion of this project possible. It has been a long journey since we began work on the project in January 2019, but a few people have been there all along the way to help us. -

1822: Cain; Conflict with Canning; Plot to Make Burdett the Whig Leader

1 1822 1822: Cain ; conflict with Canning; plot to make Burdett the Whig leader; Isaac sent down from Oxford, but gets into Cambridge. Trip to Europe; the battlefield of Waterloo; journey down the Rhine; crossing the Alps; the Italian lakes; Milan; Castlereagh’s suicide; Genoa; with Byron at Pisa; Florence; Siena, Rome; Ferrara; Bologna; Venice; Congress of Verona; back across the Alps; Paris, Benjamin Constant. [Edited from B.L.Add.Mss. 56544/5/6/7.] Tuesday January 1st 1822: Left two horses at the White Horse, Southill (the sign of which, by the way, was painted by Gilpin),* took leave of the good Whitbread, and at one o’clock (about) rode my old horse to Welwyn. Then [I] mounted Tommy and rode to London, where I arrived a little after five. Put up at Douglas Kinnaird’s. Called in the evening on David Baillie, who has not been long returned from nearly a nine years’ tour – he was not at home. Wednesday January 2nd 1822: Walked about London. Called on Place, who congratulated me on my good looks. Dined at Douglas Kinnaird’s. Byng [was] with us – Baillie came in during the course of the evening. I think 1 my old friend had a little reserve about him, and he gave a sharp answer or two to Byng, who good-naturedly asked him where he came from last – “From Calais!” said Baillie. He says he begins to find some of the warnings of age – deafness, and blindness, and weakness of teeth. I can match him in the first. This is rather premature for thirty-five years of age. -

Regeneration and ED Strategy 2016

Draft for adoption Ss1234 1 London Borough of Hounslow London Borough of Hounslow Regeneration and Economic Development Strategy 2016 - 20 Contents 1. Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... 3 2. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 4 3. Context ......................................................................................................................................... 6 4. Vision and Strategies ................................................................................................................. 9 5. Objectives .................................................................................................................................. 12 6. Objective 1 – Growing Business ........................................................................................... 17 7. Objective 2 – Improving Connectivity ............................................................................... 35 8. Objective 3 – Place-making ................................................................................................. 40 A. Town centres ........................................................................................................................ 40 B. Context and character of the borough’s places ..................................................... 52 C. Sustainable mixed communities .................................................................................... -

If You Require Further Information About This Agenda Please Contact: Anthony Lumley on 020 8583 2248 Or [email protected]

If you require further information about this agenda please contact: Anthony Lumley on 020 8583 2248 or [email protected] LOCAL STRATEGIC PARTNERSHIP A meeting of the Local Strategic Partnership will be held at the Civic Centre, Lampton Road, Hounslow on Thursday, 14 September 2006 at 6:00 pm MEMBERSHIP Councillor Mark Bowen – London Borough of Hounslow Satvinder Buttar – Hounslow Racial Equality Council CS Ali Dizaei– Metropolitan Police John Foster – Hounslow Primary Care Trust Gerard Hollingworth – London Fire Brigade Mark Gilks – London Borough of Hounslow Rory Gillert – Hounslow Voluntary Sector Forum Russell Harris – West London Business Christine Hay – Hounslow Primary Care Trust Robert Innes – London West Learning & Skills Council Councillor Peter Thompson – London Borough of Hounslow AGENDA 1. Apologies for Absence 2. Minutes (Pages 1 - 5) To confirm the minutes of the meeting held on 8 March 2006 3. Local Area Agreement Performance Report for Quarter 1 (Pages 6 - 12) Report by Councillor Peter Thompson 4. Community Plan (Pages 13 - 83) (a) Performance Update March 2006 (b) Consultation Plan (c) Framework and Content – Discussion Paper (d) Consultation Questionnaire 5. LSP Awayday Update (Pages 84 - 90) 6. LSP Stakeholder Conference Feedback (Pages 91 - 94) 7. Brentford Plan (Pages 95 - 197) 8. Any Urgent Business 9. Date of Next Meeting Meetings of the LSP are currently scheduled to be held at the Civic Centre at 6.00pm on the following dates: • Wednesday 14 December 2006 • Thursday 15 March 2007 • Thursday 14 June 2007 but please bring your diary to the meeting as it may be necessary to arrange some additional dates. -

Trade Marks Manual

Trade Marks Manual Intellectual Property Office is an operating name of the Patent Office Contents New applications .........................................................................................................3 The classification guide ..............................................................................................9 The classification addendum ..............................................................................31 Classification desk instructions ........................................................................... 55 The examination guide ...............................................................................................84 Addendum ........................................................................................................257 Certification and collective marks ........................................................................... 299 International examination guide .............................................................................. 317 Register maintenance .............................................................................................. 359 Tribunal section ....................................................................................................... 372 Trade Marks Manual 1 1. Preliminary check of the application form We check every application to make sure that it meets the requirements for filing stated in the Act and Rules. Some requirements are essential in order to obtain a filing date. Others are not essential for filing date -

At a Meeting of the Children and Young People Scrutiny Panel Held on Monday, 16 February 2015 at 7:00 Pm at the Committee Room 1, Civic Centre, Lampton Road, Hounslow

At a meeting of the Children and Young People Scrutiny Panel held on Monday, 16 February 2015 at 7:00 pm at the Committee Room 1, Civic Centre, Lampton Road, Hounslow. Present: Councillor Linda Green (Chair) Councillor Tony Louki (Vice-Chair) Councillors Candice Atterton, Harleen Atwal Hear, Samia Chaudhary, Mel Collins, Tony Louki, Paul Lynch and Alan Mitchell Zara Qureshi and Robert Was Apologies for Absence Councillor Peter Carey. Kamal Ahmad and Jacqui Corley 150. Apologies for absence, declarations of interest or any other communications from Members Apologies had been received from Jacqui Corley, Co-opted Member and Kamal Ahmad, Co- opted Member. Councillor Atterton had sent apologies for lateness. Alan Adams and Jacqui McShannon had an alternative meeting and gave apologies. Jacqui McShannon did join the meeting for a short time subsequently. Ian Duke gave apologies as he was unwell. The Chair invited any declarations of interest or other communications from members. For Item 5: ‘Arts Provision for Young People’, Councillor Mitchell declared that he wished to talk about the Dramatic Edge project in the London Borough of Richmond and should declare that he had contact with the project in the past and had hosted their events. 151. Minutes of the meeting held on 3 December 2014 The Chair noted that the minutes had been issued late and checked that all members had had the opportunity to read the minutes. It was noted as something to be corrected for the future that the names of the former youth co-opted members had been shown on the agenda front sheet.