Badminton Handbook : Training, Tactics, Competition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

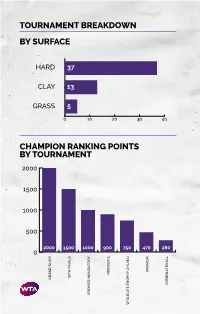

Tournament Breakdown by Surface Champion Ranking Points By

TOURNAMENT BREAKDOWN BY SURFACE HAR 37 CLAY 13 GRASS 5 0 10 20 30 40 CHAMPION RANKING POINTS BY TOURNAMENT 2000 1500 1000 500 2000 1500 1000 900 750 470 280 0 PREMIER PREMIER TA FINALS TA GRAN SLAM INTERNATIONAL PREMIER MANATORY TA ELITE TROPHY HUHAI TROPHY ELITE TA 55 WTA TOURNAMENTS BY REGION BY COUNTRY 8 CHINA 2 SPAIN 1 MOROCCO UNITED STATES 2 SWITZERLAND 7 OF AMERICA 1 NETHERLANDS 3 AUSTRALIA 1 AUSTRIA 1 NEW ZEALAND 3 GREAT BRITAIN 1 COLOMBIA 1 QATAR 3 RUSSIA 1 CZECH REPUBLIC 1 ROMANIA 2 CANADA 1 FRANCE 1 THAILAND 2 GERMANY 1 HONG KONG 1 TURKEY UNITED ARAB 2 ITALY 1 HUNGARY 1 EMIRATES 2 JAPAN 1 SOUTH KOREA 1 UZBEKISTAN 2 MEXICO 1 LUXEMBOURG TOURNAMENTS TOURNAMENTS International Tennis Federation As the world governing body of tennis, the Davis Cup by BNP Paribas and women’s Fed Cup by International Tennis Federation (ITF) is responsible for BNP Paribas are the largest annual international team every level of the sport including the regulation of competitions in sport and most prized in the ITF’s rules and the future development of the game. Based event portfolio. Both have a rich history and have in London, the ITF currently has 210 member nations consistently attracted the best players from each and six regional associations, which administer the passing generation. Further information is available at game in their respective areas, in close consultation www.daviscup.com and www.fedcup.com. with the ITF. The Olympic and Paralympic Tennis Events are also an The ITF is committed to promoting tennis around the important part of the ITF’s responsibilities, with the world and encouraging as many people as possible to 2020 events being held in Tokyo. -

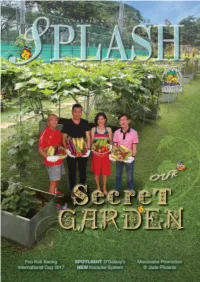

Two Is Better Than One

Two is Better Than One A non-member may now be brought to the Club as a guest TWO TIMES in a week! Don’t miss out on showing your friends around the best club in Singapore! The Premier Family Club where the People make the Difference PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE OLD ADVERSARIES MET, NEW FRIENDS MADE For the first time, Singapore Swimming Club played host to the Foo Kok Keong International Cup tournament. Over three days from 7 to 9 July, the badminton competition gathered internationally renowned stars of yesteryear from nine surrounding countries to pit their skills against one another and allowed our members to enjoy watching the superb skills at close quarters. Among the players were Hariyanto Arbi, two-time All-England champion, crowd favourite Boonsak Ponsana, Razif Sidek, Yap Kim Hock and Ong Ewe Hock, and former world number one Foo Kok Keong himself. This tournament was held outside Malaysia for the first time since its inception in 2012. We are indeed proud to be given this vote of confidence by the Cup founders to host the games. Kudos to the Organising Committee and Club staff who have done us proud with the very successful conclusion of this tournament. President playing an exhibition match at On 28 July, it was time for the Club to show appreciation to all outgoing Singapore Swimming Club–Foo Kok Keong members of the 2016/2017 Sub-Committees and Ad-Hoc Committees and International Cup 2017. welcome incoming ones with a “Thank You and Welcome” Dinner. To all involved, a big thank you for having volunteered your services to lend your expertise and experience in ensuring that the Club’s machinery functions well. -

Tennis-NZ-Roll-Of-Honour V3.Pdf

Tennis New Zealand 2012 HonourRoll of Contents New Zealand Tennis Representatives at the Olympic Games 2 ROLL OF HONOUR New Zealand Players in the final 8 at Grand Slams 2 New Zealand Players in finals at Junior Grand Slams 3 New Zealand in Davis Cup 4 Tennis New Zealand New Zealand Davis Cup Statistics 8 honours the achievements of all New Zealand in Fed Cup 10 the players and administrators National Championships 13 listed here... New Zealand Indoor Championships 16 New Zealand Residential Championships 16 BP National Championships 17 Fernleaf Butter Classic 17 Heineken Open 17 ASB Classic 18 National Teams Event for the Wilding Shield and Nunneley Casket 19 New Zealand Junior Championships 18u 20 National Junior Championships 16u 23 National Junior Championships 14u 24 National Junior Championships 12u 26 National Junior Championships 15u 27 National Junior Championships 13u 27 New Zealand Masters Championships 27 National Senior Championships 28 National Primary/Intermediate Schools Championships 38 Secondary Schools Tennis Championships 39 National Teams Event 16u 40 National Teams Event 14u 40 National Teams Event 12u 41 National teams Event 18u 41 Past Presidents and Board Chairs 42 Life Members 42 Roll of Honour 1 New Zealand Tennis Representatives at the Olympic Games YEAR GAMES NAME EVENT MEDAL 1912 Games of the V A F Wilding Men’s Singles Bronze Olympiad, Stockholm (Australasian Team) (Covered Courts) 1988 Games of the XXIV B J Cordwell Women’s Singles Olympiad, Seoul B P Derlin Men’s Doubles (K Evernden & B Derlin) K G Evernden -

The Transition and Transformation of Badminton Into a Globalized Game

Title The transition and transformation of badminton into a globalized game, 1893-2012: A study of the trials and tribulations of Malaysian badminton players competing for Thomas Cup and Olympic gold medals Author(s) Lim Peng Han Source 8th International Malaysian Studies Conference (MSC8), Selangor, Malaysia, 9 - 11 July 2012 Organised by Malaysian Social Science Association © 2012 Malaysian Social Science Association Citation: Lim, P. H. (2012). The transition and transformation of badminton into a globalized game: A study of the trials and tribulations of Malaysian badminton players competing for Thomas Cup and Olympic gold medals. In Mohd Hazim Shah & Saliha Hassan (Eds.), MSC8 proceedings: Selected full papers (pp. 172 - 187). Kajang, Selangor: Malaysian Social Science Association. Archived with permission from the copyright owner. 4 The Transition and Transformation of Badminton into a Globalised Game, 1893-2012: A Study on the Trials and Tribulations of Malaysian Badminton Players Competing for Thomas Cup and the Olympic Gold Medals Lim Peng Han Department of Information Science Loughborough University Introduction Badminton was transformed as a globalised game in four phases. The first phase began with the founding of the International Badminton Federation in 1934 and 17 badminton associations before the Second World War. The second phase began after the War with the first Thomas Cup contest won by Malaya in 1949. From 1946 to 1979, Malaysia won the Cup 4 times and Indonesia, 7 times. In 1979 twenty-six countries competed for the Cup. The third phase began with China's membership into the IBF in 1981. From 1982 to 2010 China won the Thomas Cup 8 times, Indonesia won 6 times and Malaysia, only once. -

History of Badminton

Facts and Records History of Badminton In 1873, the Duke of Beaufort held a lawn party at his country house in the village of Badminton, Gloucestershire. A game of Poona was played on that day and became popular among British society’s elite. The new party sport became known as “the Badminton game”. In 1877, the Bath Badminton Club was formed and developed the first official set of rules. The Badminton Association was formed at a meeting in Southsea on 13th September 1893. It was the first National Association in the world and framed the rules for the Association and for the game. The popularity of the sport increased rapidly with 300 clubs being introduced by the 1920’s. Rising to 9,000 shortly after World War Π. The International Badminton Federation (IBF) was formed in 1934 with nine founding members: England, Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Denmark, Holland, Canada, New Zealand and France and as a consequence the Badminton Association became the Badminton Association of England. From nine founding members, the IBF, now called the Badminton World Federation (BWF), has over 160 member countries. The future of Badminton looks bright. Badminton was officially granted Olympic status in the 1992 Barcelona Games. Indonesia was the dominant force in that first Olympic tournament, winning two golds, a silver and a bronze; the country’s first Olympic medals in its history. More than 1.1 billion people watched the 1992 Olympic Badminton competition on television. Eight years later, and more than a century after introducing Badminton to the world, Britain claimed their first medal in the Olympics when Simon Archer and Jo Goode achieved Mixed Doubles Bronze in Sydney. -

Dons Article MK News 3.Pdf

MKNEWS |onemk.co.uk |November 18, 2015 | 59 Advert ID:Folio[647781] BooFirstLastkingCustom270AppearCodColommere:Folance:ur:by5ID:Fo1io[618/1mmlio47781/151] If you want the best price for your home MKSPORT SESENDND YOUR [email protected]@mk-news.co.uk Call Wilson Peacock Milton Keynes 01908 606951 dons column mk lightning SPORTSSHORTS James Reeve NON-LEAGUE FOOTBALL posts his TAbLEtoppers LeicesterNirvana kept up Cowshed theirwinningwaysasNewport PagnellTown Commentaries were beaten5-1 in theUnited Counties Lightning to play PremierLeague. blog on our In theberks andbucks Intermediate Cup website.You thirdround,Olney Town beatbuckingham Athletic3-0 andLoughton Manor beat can get Holmer Green Reserves 6-5onpenalties involved at aftertheydrew2-2 in normaltime. Old onemk.co.uk GB U20 friendly bradwell United beat AstonClinton 4-1. In theSpartan South Midlands League BY SCOTT KIRK DivisionTwo,Stony StratfordTownlost3-2 WITH theJanuary transferwindow at Mursley United,while WolvertonTown approaching, Dons will likely look to [email protected] beatStAlbansCityReserves4-3. secure at leastone loan signingtohelp MK LIGHTNINGwill entertain them throughthe second half of the GreatBritain U20s on YOUTH FOOTBALL season. Wednesday,December 2atthe THECityColts’Lions teamwon the Butwho should theDonsbring in? MK Arena. Presidents Trophy with asuddendeath What positionsneed themosthelpand Thegamewill be oneofGB’s penaltyvictory over Wing RaidersWasps. whocan fill that role in January? finalfixtures before they head to JacobLarbi scored thewinningpenaltyand Onepersoncould be MilosVeljkovi- a France to contestdivision1Bof EesaKhansavedthree penalties throughout SerbianU21 international defender theWorld Junior Championships thecourseofthe shoot-out.Rahul Thakrar that cuRRentlyplies histrade foR in Megeve,nearChamonix, from scored Colts’ goal in normaltimeasthat TottenhamHotspur’s reserveside. 12 -18December. -

Download Article (PDF)

International Conference on Applied Social Science Research (ICASSR 2015) “Who is the Best Player of Table Tennis Champions” is the Innovation of National Fitness Zhiping LI Physical Department Civil Aviation University of China Abstract - “Who is the best player” is an important innovation tournament, which has almost increased five times compared to promote the national fitness. The successful development of this with the previous number. It is fully demonstrated that the activity has played a positive role in the increase of sports competition of “who is the best player” has promoted the population, the kindness degree of show, the expansion of hosting sports population [2]. right and the increase of economic benefit as well as the bridge construction of friendship in mainland China, Hongkong, Macao and 3. “Who is the best player” is the innovation of “seeing and Taiwan. In other words, there is no doubt that “who is the best touching” player” has played a positive role in promoting the overall development of national fitness. From January 6 to January 10 in 2014, five reports on Index Terms - table tennis, badminton, champions “Thoughts of Development of Sports Reform in Depth and Breadth” have been published in Sports Edition of “People’s 1. Introduction Daily”, which focused on the aspects of “public sports service”, “folk sports” and “bigger picture of sports development”. At Under the background of the study on national fitness and the same time, the lack of public sports service has been with Chinese table tennis tournament as the platform, this discussed and the suggestions such as “justifying the paper focuses on promoting national fitness and improving community sports organizations” and “reconstructing rather physical strength of the citizen. -

2009 Major Tournament Winners

⇧ 2010 Back to Badzine Results Page ⇩ 2008 2009 Major Tournament Winners Men's singles Women's singles Men's doubles Women's doubles Mixed doubles World Championships Lin Dan Lu Lan Cai Yun / Fu Haifeng Zhang Yawen / Zhao Tingting Thomas Laybourn / Kamilla Rytter Juhl Super Series Malaysia Open Lee Chong Wei Tine Baun Jung Jae Sung / Lee Yong Dae Lee Hyo Jung / Lee Kyung Won Nova Widianto / Liliyana Natsir Korea Open Peter Gade Tine Baun Mathias Boe / Carsten Mogensen Cheng Wen Hsing / Chien Yu Chin Lee Yong Dae / Lee Hyo Jung All England Lin Dan Wang Yihan Cai Yun / Fu Haifeng Zhang Yawen / Zhao Tingting He Hanbin / Yu Yang Swiss Open Lee Chong Wei Wang Yihan Koo Kien Keat / Tan Boon Heong Du Jing / Yu Yang Zheng Bo / Ma Jin Singapore Open Bao Chunlai Zhou Mi Anthony Clark / Nathan Robertson Zhang Yawen / Zhao Tingting Zheng Bo / Ma Jin Indonesia Open Lee Chong Wei Saina Nehwal Jung Jae Sung / Lee Yong Dae Chin Eei Heui / Wong Pei Tty Zheng Bo / Ma Jin Japan Open Bao Chunlai Wang Yihan Markis Kido / Hendra Setiawan Ma Jin / Wang Xiaoli Songphon Anugritayawon / Kunchala Voravichitchaikul China Masters Lin Dan Wang Shixian Guo Zhendong / Xu Chen Du Jing / Yu Yang Tao Jiaming / Wang Xiaoli Denmark Open Simon Santoso Tine Baun Koo Kien Keat / Tan Boon Heong Pan Pan / Zhang Yawen Joachim Fischer-Nielsen / Christinna Pedersen French Open Lin Dan Wang Yihan Markis Kido / Hendra Setiawan Ma Jin / Wang Xiaoli Nova Widianto / Liliyana Natsir Hong Kong Open Lee Chong Wei Wang Yihan Jung Jae Sung / Lee Yong Dae Ma Jin / Wang Xiaoli Robert Mateusiak -

Strategic Plan 2016-2020

BADMINTON CONFEDERATION AFRICA STRATEGIC PLAN 2016-2020 About this Document The purpose of this document is to outline the strategic direction of the Badminton Confederation Africa (BCA) as a Continental Badminton Confederation for Africa. This document begins with a general introduction of the organisation, the planning process and a brief overview of the strategic plan. The second part of this document details the individual goals and objectives of each strategic areas and priorities. Expected outcomes or key performance indicators are also detailed in the second part. For consistency with the Badminton World Federation and in view of the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games, this plan has a time frame of 4 years starting 2016 to 2020. Even though this reference period mainly covers the next four years the plan also outline measures which may go beyond this period and can only be reached at a later stage. While this strategic plan will eventually be implemented by BCA Operations, it has to be recognised by all stakeholders and partners and their involvement will be vital for the success of the plan. Consequently, this plan also represents a communication tool to create a common vision and clear objectives on the horizon to work towards for all stakeholders and partners. The Badminton Confederation Africa Badminton Confederation is the continental governing body for the sport commonly known as Badminton in the African territory. The head office of the Confederation is in Quatre Bornes, Mauritius. Badminton World Federation recognizes BCA as a Continental Confederation alongside the other Continental Confederation – Badminton Asia, Badminton Europe, Badminton Pan Am Confederation and Badminton Oceania. -

25 Countries to Compete at Singapore Badminton Open 2019 As Registration Closed Badminton Powerhouses Indonesia, Korea and Denmark Latest to Announce Entry

PRESS RELEASE 25 countries to compete at Singapore Badminton Open 2019 as registration closed Badminton Powerhouses Indonesia, Korea and Denmark latest to announce entry [Singapore, 27 February 2019] – The 2019 edition of the Singapore Badminton Open is set to be action packed with all the World Number 1 shuttlers confirming their participation for the tournament in April. The final day of registration saw the likes of Marcus Fernaldi Gideon and Kevin Sanjaya Sukamuljo amongst the latest entries that will be in contention at the Singapore Indoor Stadium from 9-14 April. Part of the HSBC BWF World Tour Series, the Singapore leg boasts a star-studded line-up that would undoubtedly send waves of excitement through the badminton scene. Gideon and Sukamuljo completes the list of World Ranked #1 shuttlers that will compete at the Singapore Open. The Men’s Doubles Asian Games 2018 champions will be part of a 50 strong contingent from Indonesia heading to The Republic. The Indonesian pair will be joined by compatriots Anthony Sinisuka Ginting, ranked #7 in the World and World Ranked #9 Jonatan Christie, also a 2018 Asian Games champion. Ginting and Christie enters what is already a stellar Men’s Singles category, alongside the likes of Kento Momota, Lin Dan, Chen Long and Chou Tien Chen. Representing Denmark in Men’s Singles will be World Ranked #6 Viktor Axelsen, he will be accompanied by fellow countrymen and former European champion Jan O Jorgensen. Amongst their ranks is also Danish starlet, Anders Antonsen, who most recently stunned Momota when he overcame the World Number 1 at the 2019 Indonesia Masters. -

Agen Allianz Life Yang Berlisensi Syariah Aktif Per 31 Mei 2021.Pdf

DAFTAR AGEN YANG BERLISENSI SYARIAH AKTIF - AS OF 31 MEI 2021 NO AGENT_NAME LICENSE_NUMBER 1 A A AYU MANIK AW 3321012036482020 2 A ARI KARUNIAWAN 3321012006150020 3 A SALAM MUHAMMADONG 3321011025615319 4 A. A PUTU EKA PARYANTI 3321012008479521 5 A. BAROIL 3321012052451719 6 A. HARIS 3321012076460320 7 A. INDRA JAYA 14902553S 8 A. M. GANDA MARPAUNG 3321012010214720 9 A. M. YUDHISTIRA SEKUNDHITA 3321012010295421 10 A. RETNO KUSWARDHANI 3321012074445020 11 A. ROBITH SYA'BANI 3321012097213820 12 A. TIKA WIDYAWARDHANI 3321012044831519 13 A.D. KUSUMA WARDHANA 3321012002801320 14 AAN CHAERANI 3321011025616819 15 AAN DARMAWAN 3321012020846021 16 AAN DIANA 3321012064398519 17 AAN HANDOKO ANG 14443135S 18 AAN JUNAIDI 3321012027911420 19 AAN SAHIDA 3321012019837621 20 AANG YONDA ANGELA 11021161S 21 AARON ABIA JUNIAS 3321012051539419 22 AARON ADHIPUTRA WIJAYA 3321012028297020 23 AB ROHMAN 3321012016588221 24 ABANG IBNU SYAMSURIZAL 10063318S 25 ABBIET SUBIYAKTO 11075737S 26 ABD FAISAL HULA 14073438S 27 ABD HALIM 14897951S 28 ABD RHAKHMAN RAMLI 3321012001302720 29 ABDI ALAMSYAH HARAHAP 11328895S 30 ABDI SOMAD 3321012014853221 31 ABDILLAH PAHRESI 3321012031421720 32 ABDIUSTIAWAN 3321012097978220 33 ABDUL AZIS 3321012004080821 34 ABDUL AZIZ 3321012098577620 35 ABDUL FATAH 3321012091888520 36 ABDUL FIKRI GUNAWAN 3321012010309021 37 ABDUL HAKIM GALIB BELFAS 3321012016206421 38 ABDUL HARIS 14473674S 39 ABDUL HARIST GANI 3321012028298420 40 ABDUL JALIL 3321012001457020 41 ABDUL RACHMAN 14888820S 42 ABDUL RACHMAN N 3321012066747519 43 ABDUL RAHMAN 3321012038907219 -

Suwalski Klub Badmintona 16 XI 1987 – 16 XI 2013

Jerzy Szleszyński Suwalski Klub Badmintona 16 XI 1987 – 16 XI 2013 Suwałki 2013 1 Talem habebis fructum, qualis fuerit labor. (Taki będziesz miał owoc, jaka będzie praca) Przedmowa Sport, w tym badminton, jest istotną częścią mojego życia. Natura moja przejawia zainteresowania wieloma dziedzinami życia. Lubię kino, teatr, wszelką inną sztukę, ale sport uwielbiam. Jest on zjawiskiem niezwykłej natury. Najpierw był sposobem na dobrą zabawę, rozrywką zapełniającą czas wolny, służył ubarwieniu codzienności. Niezauważalnie, na przestrzeni lat, a może wieków, stał się niezmiernie istotnym fragmentem życia człowieka i narodów. Zaczął budzić namiętność, czasem histerię. Prowadził do euforii nie tylko jednostki, ale i narody. Daje radość, ale także smutek czy wręcz gorycz. Sport coraz częściej wykracza poza areny sportowe zwłaszcza w społeczeństwach usportowionych. My, Polacy, do takich narodów nie należymy. Nie jesteśmy także narodem zwycięzców. A mentalność zwycięzcy jest w sporcie koniecznością. Brak sukcesów to efekt nie tylko mentalności. To także efekt niedoskonałości organizacji sportowego (nie tylko) życia, brak odpowiednich rozwiązań, brak odpowiednich finansów, a także wiele nonsensów, których nie udaje się usunąć. Zatem należy spróbować zadać kłam powyższemu przez swoje działania. Sport inspirował mnie od najmłodszych lat: od kiedy, jako dziecko, z przyklejonym uchem do głośnika radiowego słuchałem sprawozdań znakomitych dziennikarzy, gdy jako nastolatek niewiarygodnie często reprezentowałem szkoły we wszelkich prawie dyscyplinach sportu i przez całe blisko 40 lat mojej pracy prawniczej. Sport nie jest bez skazy, ale pomaga człowiekowi definiować jego główne cele życiowe. Może więc być drogowskazem. Od lat kilku widzę konieczność spisania zdarzeń i wyczynów, które były udziałem suwalskiego badmintona na przestrzeni kilkudziesięciu lat. Opisać ewolucję jego i historię zarówno w kontekście zawodników jak i ludzi, którzy go organizowali.