[Sample B: Approval/Signature Sheet]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

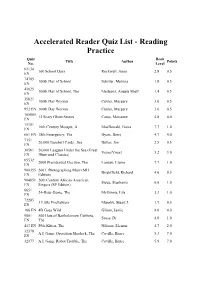

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No. Level 61130 100 School Days Rockwell, Anne 2.8 0.5 EN 74705 100th Day of School Schiller, Melissa 1.8 0.5 EN 41025 100th Day of School, The Medearis, Angela Shelf 1.4 0.5 EN 35821 100th Day Worries Cuyler, Margery 3.0 0.5 EN 952 EN 100th Day Worries Cuyler, Margery 3.0 0.5 105005 13 Scary Ghost Stories Carus, Marianne 4.8 4.0 EN 11101 16th Century Mosque, A MacDonald, Fiona 7.7 1.0 EN 661 EN 18th Emergency, The Byars, Betsy 4.7 4.0 7351 20,000 Baseball Cards...Sea Buller, Jon 2.5 0.5 EN 30561 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Great Verne/Vogel 5.2 3.0 EN Illustrated Classics) 65532 2000 Presidential Election, The Landau, Elaine 7.7 1.0 EN 900355 2061: Photographing Mars (MH Brightfield, Richard 4.6 0.5 EN Edition) 904851 20th Century African American Sigue, Stephanie 6.6 1.0 EN Singers (SF Edition) 6651 24-Hour Genie, The McGinnis, Lila 3.3 1.0 EN 72205 3 Little Firefighters Murphy, Stuart J. 1.7 0.5 EN 166 EN 4B Goes Wild Gilson, Jamie 4.6 4.0 9001 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins, Seuss, Dr. 4.0 1.0 EN The 413 EN 89th Kitten, The Nilsson, Eleanor 4.7 2.0 32378 A.I. Gang: Operation Sherlock, The Coville, Bruce 5.3 7.0 EN 32377 A.I. Gang: Robot Trouble, The Coville, Bruce 5.9 7.0 Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No. -

Festive Funnies

FINAL-1 Sat, Dec 7, 2019 5:24:40 PM tvupdateYour Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment For the week of December 15 - 21, 2019 Festive Funnies Homer from INSIDE “The Simpsons” •Sports highlights Page 2 •TV Word Search Page 2 •Family Favorites Page 4 •Hollywood Q&A Page14 Cuddle up for a festive, fun-filled night on Fox, when TV’s funniest animated families are featured in four new Christmas specials that air on Sunday, Dec. 15. The festive episode of “The Simpsons” is the show’s 20th Christmas special, while “Bless the Harts” is celebrating its first. Add to that a “Bob’s Burgers” special and one from “Family Guy,” and you’ve got a full night of holiday fun. WANTED MOTORCYCLES, SNOWMOBILES, OR ATVS GOLD/DIAMONDS ✦ 40 years in business; A+ rating with the BBB. ✦ For the record, there is only one authentic CASH FOR GOLD, Bay 4 Group Page Shell PARTS & ACCESSORIES We Need: SALESMotorsports & SERVICE 5 x 3” Gold • Silver • Coins • Diamonds MASS. MOTORCYCLEWANTED1 x 3” We are the ORIGINAL and only AUTHENTIC SELLBUYTRADEINSPECTIONS Score More CASH FOR GOLD on the Methuen line, above Enterprise Rent-A-Car Sales This Winter at 527 So. Broadway, Rte. 28, Salem, NH • 603-898-2580 1615 SHAWSHEEN ST., TEWKSBURY, MA CALL (978)946-2000 TO ADVERTISE PRINT • DIGITAL • MAGAZINE • DIRECT MAIL Open 7 Days A Week ~ www.cashforgoldinc.com 978-851-3777 WWW.BAY4MS.COM FINAL-1 Sat, Dec 7, 2019 5:24:42 PM COMCAST ADELPHIA 2 Sports Highlights Kingston CHANNEL Atkinson Sunday 1:30 p.m. ESPN NFL Live Live 6:00 p.m. -

Department of English and American Studies Queer

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Katerina Hasalova Queer American Television: The Development of Lesbian Characters Master’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Jeffrey Alan Vanderziel, B.A. 2013 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author’s signature Acknowledgement I would like to thank the thesis supervisor Jeffrey Alan Vanderziel, B.A., for his support and inspiration Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................... 1 Historical Overview ......................................................................................... 4 The Early Years: Pre-Stonewall to the 1970s .................................................. 4 The 1980s ................................................................................................... 5 The 1990s ................................................................................................... 8 The 2000s ................................................................................................. 12 The 2010s ................................................................................................. 17 Meet the Creators, Shows and Characters ....................................................... 21 Criteria ...................................................................................................... 21 -

Hearing Voices

FINAL-1 Sat, Dec 28, 2019 5:50:57 PM tvupdateYour Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment For the week of January 5 - 11, 2020 Hearing voices Jane Levy stars in “Zoey’s Extraordinary Playlist” INSIDE •Sports highlights Page 2 •TV Word Search Page 2 •Family Favorites Page 4 •Hollywood Q&A Page14 In an innovative, exciting departure from standard television fare, NBC presents “Zoe’s Extraordinary Playlist,” premiering Tuesday, Jan. 7. Jane Levy (“Suburgatory”) stars as the titular character, Zoey Clarke, a computer programmer whose extremely brainy, rigid nature often gets in the way of her ability to make an impression on the people around her. Skylar Astin (“Pitch Perfect,” 2012), Mary Steenburgen (“The Last Man on Earth”). John Clarence (“Luke Cage”), Peter Gallagher (“The O.C.”) and Lauren Graham (“Gilmore Girls”) also star. WANTED MOTORCYCLES, SNOWMOBILES, OR ATVS GOLD/DIAMONDS ✦ 40 years in business; A+ rating with the BBB. ✦ For the record, there is only one authentic CASH FOR GOLD, Bay 4 Group Page Shell PARTS & ACCESSORIES We Need: SALESMotorsports & SERVICE 5 x 3” Gold • Silver • Coins • Diamonds MASS. MOTORCYCLEWANTED1 x 3” We are the ORIGINAL and only AUTHENTIC SELLBUYTRADEINSPECTIONS Score More CASH FOR GOLD on the Methuen line, above Enterprise Rent-A-Car Sales This Winter at 527 So. Broadway, Rte. 28, Salem, NH • 603-898-2580 1615 SHAWSHEEN ST., TEWKSBURY, MA CALL (978)946-2000 TO ADVERTISE PRINT • DIGITAL • MAGAZINE • DIRECT MAIL Open 7 Days A Week ~ www.cashforgoldinc.com 978-851-3777 WWW.BAY4MS.COM FINAL-1 Sat, Dec 28, 2019 5:50:58 PM COMCAST ADELPHIA 2 Sports Highlights Kingston CHANNEL Atkinson Sunday 11:00 p.m. -

Of Goal "Iextend to You My Heartfelt Thanks for Sending to Me the Wingfoot Last ' Clan

Wounded Goodyear Man Is ToldHis Fighting Days Over; Soon Comes Home David Ferguson In Fierce Battles Of Pacific = = AKRON EDITION = I NAME PROTECT OUR GOOD David S. Ferguson, who left tated home. Uncle Sam tells his job in Dept. 137C, spreader me that because of my present AKRON, OHIO, room, Plant 1, in August, 1942, condition Iam to do no more Vol. 33 WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 25, 1944 No. 43 fighting." David, a statf sergeant, says he has traveled thousands of miles,— both on water and land seeing action in New Ca'e- Goodyear War donia, islands, Chest Fund the Solomon the New Hebrides and all "up and down the line," as he puts it, "ending up on Bougainville is- land." Still Not In Sight Of Goal "Iextend to you my heartfelt thanks for sending to me The Wingfoot last ' Clan. The time tmS- '■&**BmmmW BB' ■«! Iwrote to vou Iwas fighting in ONLY THREE Bk| -.—|flP^ the front lines," says David. Each Gives $10 To United War Chest "We all appreciate the co- operation Goodyear has given DAYS REMAIN our boys. We believe in you, so please do not let us down. "You sneak of medals. What IN CAMPAIGN are my four or five medals in comparison with the sweat, Committee's Opinion Many *^ vBBBBBBB BBrBfew hard work and longhours Good- Don't B_—^P" iHB B wB T year workers put in ? Keep up Understand What the good— spirit and work for one Their Cash Will Buy sause to end this war. "We down here will keep Old As the UnitedWar Chest cam- Glory flying, so Uncle Sam can paign at Goodyear swings into feel proud of our boys." its lastlap, with only three days to go, solicitors Sergeant Ferguson's wife, ' committees and ' - are making a valiant effort to Julia, is emploved in Dept. -

BACK on TRACK LUCKY THIRTEEN >SPENT IT= SPECIAL AT

MONDAY, AUGUST 11, 2014 732-747-8060 $ TDN Home Page Click Here BACK ON TRACK >SPENT IT= SPECIAL AT SARATOGA Struggling to find his form in his native Britain this Alex and JoAnn Lieblong=s I Spent It (Super Saver), term, David Armstrong and Cheveley Park Stud=s who became his freshman sire (by Maria=s Mon)=s first Garswood (GB) winner in his Belmont debut July 2, also became the (Dutch Art {GB}) first graded stakes revived his fortunes winner for Super Saver to cause an upset on when he took the his favored testing GII Saratoga Special S. ground in Deauville=s in professional fashion G1 Prix Maurice de Sunday. The colt was Gheest. Entering this purchased by W D off a fourth in the G2 North for $65,000 at Lennox S. that he the Fasig-Tipton had garnered in 2013 October Sale and, Garswood after breezing in 9 4/5, Scoop Dyga over seven furlongs resold for $600,000 at Glorious from the Eddie Woods Goodwood 12 days ago, the bay was off the bridle I Spent It NYRA Photo consignment at the from the outset, but eventually found his feet and, after Fasig-Tipton Florida gaining the lead approaching the furlong pole, stayed Sale. In his debut, the bay stalked the pace and inched on to best Thawaany (Ire) (Tamayuz {GB}) by a half away late for the victory, earning a 7 Thoro-Graph length. In doing so, he went one better than his sire, number. who was second in this seven years ago. AHe has been I Spent It was away well from the inside and tracked very frustrating in England, but he needs it soft,@ Emma along the rail in third behind leader Nonna=s Boy Armstrong, wife of part-owner David, explained. -

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Book Quiz ID Title Author Pts Level 17352 EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro Basketball Italia, Bob 6.5 1 17354 EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro Golf Italia, Bob 5.6 1 28974 EN 101 Questions Your Brain Has Asked... Brynie, Faith 8.1 6 18751 EN 101 Ways to Bug Your Parents Wardlaw, Lee 3.9 5 14796 EN 13th Floor: A Ghost Story, The Fleischman, Sid 4.4 4 39863 EN 145th Street: Short Stories Myers, Walter Dean 5.1 6 26051 EN 14th Dalai Lama: Spiritual Leader of Tibet, The Stewart, Whitney 8.4 3 53617 EN 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Grace/Bruchac 7.1 1 44803 EN 1776: Son of Liberty Massie, Elizabeth 6.1 9 35293 EN 1812 Nevin, David 6.5 32 44804 EN 1863: A House Divided Massie, Elizabeth 5.9 9 44805 EN 1870: Not with Our Blood Massie, Elizabeth 4.9 6 44511 EN 1900-10: New Ways of Seeing Gaff, Jackie 7.7 1 53175 EN 1900-20: A Shrinking World Parker, Steve 7.8 0.5 53513 EN 1900-20: Linen & Lace Mee, Sue 7.3 1 56505 EN 1900-20: New Horizons (20th Century-Music) Hayes, Malcolm 8.4 1 40855 EN 1900-20: The Birth of Modernism Gaff, Jackie 8.6 1 44512 EN 1910-20: The Birth of Abstract Art Gaff, Jackie 7.6 1 53176 EN 1920-40: Atoms to Automation Parker, Steve 7.9 1 44513 EN 1920-40: Realism and Surrealism Gaff, Jackie 8.3 1 48779 EN 1920s: Luck, The Hoobler, Dorothy/Tom 4.4 3 48780 EN 1930's: Directions, The Hoobler, Dorothy/Tom 4.5 4 44514 EN 1940-60: Emotion and Expression Gaff, Jackie 7.9 1 53177 EN 1940-60: The Nuclear Age Parker, Steve 7.7 1 36116 EN 1940s from World War II to Jackie Robinson, -

Explore Cape May County's Past

Volume 34, Number 1 Listed on the NJ State Register of Historic Places on September 27, 2016 2019 Explore Cape May County’s Past Celebrating 46 Years of History Education and Preservation WELCOME Historic Cold Spring Village opened to the What were the arduous household tasks the public in May 1981 with a three-fold mission women of the family needed to perform? Many of historic preservation, history education and of them were the very same jobs needed to heritage tourism. Its primary goal is to inform maintain a current home; only they were done visitors about how our ancestors lived and without the advantages of modern technology. worked two centuries ago. Among the many One household chore common to both our lovingly restored buildings where visitors can ancestors and ourselves was washing the fam- learn about the museum from our skilled and ily’s clothes, a task made easier today thanks friendly interpreters are a one-room school, to washing machines and dryers. However, INSIDE a tavern-hotel, a blacksmith shop, a basket- washing clothes in Early America was a daunt- Village Map ........................................................................................................... Page 2 making shop, a woodworking shop and a tin- ing task. Typically, two large, heavy iron caul- "The Cold Spring" ................................................................................................. Page 1 smithing shop. These artisans demonstrate the drons had to be set up outside, suspended from Historic Cold Spring Village Membership ............................................................ Page 3 physically demanding tasks and trades of an iron tripods. The children would take yokes, Building Key .......................................................................................................... Page 3 age long gone. designed for carrying buckets of water filled Calendar of Events 2019 ...................................................................................... -

Relieving Pain in America: a Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research

This PDF is available from The National Academies Press at http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=13172 Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research ISBN Committee on Advancing Pain Research, Care, and Education; Institute of 978-0-309-25627-8 Medicine 382 pages 6 x 9 PAPERBACK (2011) Visit the National Academies Press online and register for... Instant access to free PDF downloads of titles from the NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES NATIONAL ACADEMY OF ENGINEERING INSTITUTE OF MEDICINE NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL 10% off print titles Custom notifcation of new releases in your feld of interest Special offers and discounts Distribution, posting, or copying of this PDF is strictly prohibited without written permission of the National Academies Press. Unless otherwise indicated, all materials in this PDF are copyrighted by the National Academy of Sciences. Request reprint permission for this book Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research Committee on Advancing Pain Research, Care, and Education Board on Health Sciences Policy Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS 500 Fifth Street, N.W. Washington, DC 20001 NOTICE: The project that is the subject of this report was approved by the Governing Board of the National Research Council, whose members are drawn from the councils of the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, and the Institute of Medicine. The members of the committee responsible for the report were chosen for their special competences and with regard for appropriate balance. -

ED431868.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 431 868 CE 077 566 TITLE Focus on Basics, 1998. INSTITUTION National Center for the Study of Adult Learning and Literacy, Boston, MA. SPONS AGENCY Office of Educational Research and Improvement (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 1998-00-00 NOTE 118p. CONTRACT R309B60002 AVAILABLE FROM Focus on Basics, 44 Farnsworth St., Boston, MA 02210-1211; e-mail: [email protected] PUB TYPE Collected Works - Serials (022) JOURNAL CIT Focus on Basics; v2 n1-4 1998 EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Academic Persistence; Adult Basic Education; *Adult Literacy; Educational Change; *Educational Practices; *Educational Research; *Literacy Education; *Outcomes of Education; Program Effectiveness; Student Motivation; *Teaching Methods IDENTIFIERS *General Educational Development Tests ABSTRACT This volume contains the four 1998 quarterly issues of this newsletter that present best practices, current research on adult learning and literacy, and information on how research is used by adult basic education teachers, counselors, program administrators, and policy makers. The following are among the major articles included: "Power, Literacy, and Motivation" (Greg Hart); "The First Three Weeks: A Critical Time for Motivation" (B. Allan Quigley); "Build Motivation by Building Learner Participation" (Barbara Garner); "Staying in a Literacy Program" (Archie Willard); "Stopping Out, Not Dropping Out" (Alisa Belzer); "Where Attendance Is Not a Problem" (Moira Lucey); "Getting into Groups" (Michael Pritza); "The GED [General Educational Development Test]: Whom Does It Help?" (John H. Tyler); "Project-Based Learning and the GED" (Anson M. Green); "Describing Program Practice: A Typology across Two Dimensions" (Barbara Garner); "Retention and the GED" (Jamie D. Barron Jones); "The Spanish GED" (Anastasia K. -

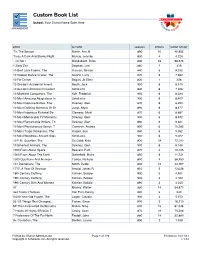

Custom Book List

Custom Book List School: Your District Name Goes Here MANAGEMENT BOOK AUTHOR LEXILE® POINTS WORD COUNT 'Tis The Season Martin, Ann M. 890 10 40,955 'Twas A Dark And Stormy Night Murray, Jennifer 830 4 4,224 ...Or Not? Mandabach, Brian 840 23 98,676 1 Zany Zoo Degman, Lori 860 1 415 10 Best Love Poems, The Hanson, Sharon 840 6 8,332 10 Coolest Dance Crazes, The Swartz, Larry 870 6 7,660 10 For Dinner Bogart, Jo Ellen 820 1 328 10 Greatest Accidental Inventi Booth, Jack 900 6 8,449 10 Greatest American President Scholastic 840 6 7,306 10 Mightiest Conquerors, The Koh, Frederick 900 6 8,034 10 Most Amazing Adaptations In Scholastic 900 6 8,409 10 Most Decisive Battles, The Downey, Glen 870 6 8,293 10 Most Defining Moments Of Th Junyk, Myra 890 6 8,477 10 Most Ingenious Fictional De Clemens, Micki 870 6 8,687 10 Most Memorable TV Moments, Downey, Glen 900 6 8,912 10 Most Remarkable Writers, Th Downey, Glen 860 6 9,321 10 Most Revolutionary Songs, T Cameron, Andrea 890 6 10,282 10 Most Tragic Romances, The Harper, Sue 860 6 9,052 10 Most Wondrous Ancient Sites Scholastic 900 6 9,022 10 P.M. Question, The De Goldi, Kate 830 18 72,103 10 Smartest Animals, The Downey, Glen 900 6 8,148 1000 Facts About Space Beasant, Pam 870 4 10,145 1000 Facts About The Earth Butterfield, Moira 850 6 11,721 1000 Questions And Answers Tames, Richard 890 9 38,950 101 Dalmatians, The Smith, Dodie 830 12 44,767 1777: A Year Of Decision Arnold, James R. -

Six Reasons Why Feral House Mouse Populations Might Have Low Recapture Rates

Wdl. Res., 1994, 21, 559-67 Six Reasons Why Feral House Mouse Populations Might Have Low Recapture Rates Charles J. Krebs, Grant R. Singleton and Alice J. Kenney CSIRO Division of Wildlife and Ecology, PO Box 84, Lyneham, ACT 2602, Australia. Abstract Many feral house mouse populations have low recapture rates (0-20%) in live-trapping studies carried out at 2-4-week intervals. We consider six hypotheses to explain low recapture rates. We radio-collared 155 house mice between September 1992 and May 1993 in agricultural fields on the Darling Downs of south-eastern Queensland during a phase of population increase. Low recapture rates during the breeding season were due to low trappability and during the non-breeding period to nomadic movements. During the breeding season radio-collared mice of both sexes survived well and moved mostly small distances (<ll m). Low trappability has consequences for the precision of population indices that rely on catch per unit effort. Capture-recapture models robust to heterogeneity of trap responses should be used to census feral Mus populations. Introduction One of the most characteristic features of mark-recapture studies of feral house mice (Mus domesticus) is that there is a very low recapture rate of marked individuals. While similar studies of voles and mice have recapture rates of 60-100% when samples are taken every few weeks (Krebs and Boonstra 1984), for feral house mouse populations recapture rates of 0-20% are the norm. Singleton (1987) reported recapture rates of 11-20% for Longworth live-traps at monthly intervals. In southern Queensland Willliams and Wilson (1980) found only 19% of 2253 tagged mice were caught one month later.