Conflict Between Philosophical Beliefs About Language Arts Instruction and District Mandates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metafora Konseptual Dalam Lukas Graham 3 the Purple Album: Analisis Semantik Kognitif

Volume 9, No. 2, September 2020 p–ISSN 2252-4657 DOI 10.22460/semantik.v9i2.p85-92 e–ISSN 2549-6506 METAFORA KONSEPTUAL DALAM LUKAS GRAHAM 3 THE PURPLE ALBUM: ANALISIS SEMANTIK KOGNITIF Afni Apriliyanti Devita 1, Tajudin Nur 2 1 Fakultas Ilmu Budaya Universitas Padjadjaran, Jl. Raya Bandung Sumedang KM.21, Hegarmanah, Kec. Jatinangor, Kabupaten Sumedang, Jawa Barat 45363 2 Fakultas Ilmu Budaya Universitas Padjadjaran, Jl. Raya Bandung Sumedang KM.21, Hegarmanah, Kec. Jatinangor, Kabupaten Sumedang, Jawa Barat 45363 1 [email protected] 2 [email protected] Received: December 19, 2019; Accepted: September 5, 2020 Abstract This study is a cognitive semantik analysis regarding the use of metaphors in song lyrics. The method used is the descriptive qualitative. Lukas Graham is a band from Denmark. The data were taken from 10 songs of Lukas Graham’s 3 The Purple Album. The aims of this study are to discuss (1) metaphorical characteristics in Lukas Graham’s 3 The Purple Album, (2) metaphorical types in Lukas Graham’s 3 The Purple Album, and (3) image schemes contained in Lukas Graham’s 3 The Purple Album. The theory used are the conceptual metaphor of Lakoff and Johnson (2003) as the main theory and the image scheme of Croft & Cruse (2004). The result showed 21 data of conceptual metaphor with 15 ontological metaphors, 2 orientational metaphors, and 4 structural metaphors. The ontological metaphors is the most dominant in Lukas Graham 3 The Purple Album. The image scheme found in the study were 3 scheme containers, 3 scheme unities, 9 scheme existences, 4 scheme identities, and 2 scheme spaces. -

Reading in the Twentieth Century. INSTITUTION Center for the Improvement of Early Reading Achievement, Ann Arbor, MI

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 479 530 CS 512 338 AUTHOR Pearson, P. David TITLE Reading in the Twentieth Century. INSTITUTION Center for the Improvement of Early Reading Achievement, Ann Arbor, MI. SPONS AGENCY Office of Educational Research and Improvement (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 2000-08-00 NOTE 46p.; CIERA Archive #01-08. CONTRACT R305R70004 AVAILABLE FROM CIERA/University of Michigan, 610 E. University Ave., 1600 SEB, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1259. Tel: 734-647-6940; Fax: 734- 763 -1229. For full text: http://www.ciera.org/library/archive/ 2001-08/0108pdp.pdf. PUB TYPE Information Analyses (070). Reports Research (143) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Educational History; *Educational Practices; Futures (of Society); Instructional Materials; *Reading Instruction; *Reading Processes; *Reading Research; Reading Skills; Teaching Methods IDENTIFIERS *Reading Theories ABSTRACT This paper discusses reading instruction in the 20th century. The paper begins with a tour of the historical pathways that have led people, at the century's end, to the "rocky and highly contested terrain educators currently occupy in reading pedagogy." After the author/educator unfolds his version of a map of that terrain in the paper, he speculates about pedagogical journeys that lie ahead in a new century and a new millennium. Although the focus is reading pedagogy, the paper seeks to connect the pedagogy to the broader scholarly ideas of each period. According to the paper, developments in reading pedagogy over the last century suggest that it is most useful to divide the century into thirds, roughly 1900-1935, 1935- 1970, and 1970-2000. The paper states that, as a guide in constructing a map of past and present, a legend is needed, a common set of criteria for examining ideas and practices in each period--several candidates suggest themselves, such as the dominant materials used by teachers in each period and the dominant pedagogical practices. -

Vocabulary Studies: Summarized, Reviewed, Critiqued, and Offered in an Historical Perspective

DOCUMENT RESUME 1. .ED 219 717 CS 006 716 AUTI&R Barnes, Nancy Marie Van- Stavern; Barnes, James Albert, Jr. TITLE Vocabulary Studies: Summarized, Reviewed, Critiqued, and Offered in an Historical Perspective. PUB DATE [75] NOTE 101p. \_ EDRS PRICE' ' MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Child Language; Literatureyeviews; Oral Language; Primary Education; *Reading Research; *Structural Analysis (Linguistics); Textbook Content; *Vocabulary; *Vocabulary Development; *Word Frequency; *Word Lists ABSTRACT To offer a historical perspective on vocabulary studies, this paper presents summaries, reviews, and critiques of vocabulary studies in chronological order of publication. The only variance from this format bre published rebuttals and/or critiques, which are presented immediately following the original studies. The paper is divided into two parts. Part one presents the "Early Studies: Pre-1950" and contains the studies thatwere published before 1950. Part two presents "More Recent Studies: Post-1950" and contains the studies published since 1950. No attempt is made to classify the studies except in historical sequence. Basically the studies are concerned with the reading, writing, and spoken vocabulary of yourTh children, in grades one, two, and three. Also, "original"'and primary sources are used, not secondary. Thepaper concludes With a summation of the studies, noting that while.the earlier studies were mainly concerned with an analysis of vocabulary through frequency word counts and comparison of previously published lists, the last three decades from the 1950s to the present give evidence of a shift in emphasis to a linguistic analysis of the language. An extensive bibliogtaphy is included. (HOD) ***********************************************************************t * keproductions supplied by EDRS are the best thatcan be made A * * from the original document. -

Październik 09/2018

2zł Jesień niesie ze sobą ponury czas, świat za ok- nami traci swoje barwy, a nas dopada jesien- na chandra. Nauka i lekcje przychodzą nam z coraz więk- szą trudnością, ale w ten czas humor poprawi nowe wydanie Szkolnej Gazetki SQLPress. Zapraszamy do miłej lektury, obfitej w wiele ciekawych tematów. Redaktor naczelna Październik 09/2018 1 2 Absolwent Dietetyki SALON MATURZYSTY Absolwent Dietetyki ma bardzo szerokie możliwości poszukiwania Żywienie człowieka to jedna z dziedzin nauki, które przeżywają ostatnio zatrudnienia. Zwykle kieruje swoje pierwsze kroki do publicznych i prawdziwy renesans. Od kilkunastu lat ludzie zyskują coraz większą niepublicznych placówek ochrony zdrowia. Gdy zyska już doświad- świadomość żywieniową, dzięki ogólnemu rozwojowi branży spożywc- czenie zawodowe oraz osiągnie pierwsze sukcesy, otwiera własny zej. Wraz z systematycznym zwiększaniem oferty na rynku żywie- gabinet dietetyczny, w którym przyjmuje pacjentów i prowadzi kon- niowym, rosną budżety przeznaczane na marketing tej branży. Paradok- sultacje dietetyczne. W swojej pracy współdziała z lekarzami i tera- salnie - o wiele trudniej zrobić teraz zdrowe zakupy niż przed laty, kiedy lista produktów spożywczych w sklepach była bardzo uboga. Te wszys- peutami. tkie uwarunkowania sprawiają, że ludzie potrzebują fachowej pomocy i edukacji w dziedzinie dietetyki. Oto niektóre akademie w których możesz studiować dietetykę: Gdański Uniwersytet Medyczny Uniwersytet Medyczny im. K. Marcinkowskiego w Poznaniu Uniwersytet Medyczny w Białymstoku Wydział Nauk o Zdrowiu Kandydat na Dietetykę W zależności od wybranej uczelni, kandydaci przechodzą różne Uniwersytet Medyczny w Łodzi procedury rekrutacyjne. Najczęściej spotykanym kryterium przyję- cia na te studia jest konkurs świadectw ze szczególnym uwzględnieniem biologii, chemii oraz języków obcych. Przedmioty te są fundamentem wiedzy przyszłych dietetyków, dlatego warto postarać się już w szkole średniej o dobre wyniki matury. -

Open a World of Possible: Real Stories About the Joy and Power of Reading © 2014 Scholastic 5 Foreword

PEN OA WORLD OF POssIBLE Real Stories About the Joy and Power of Reading Edited by Lois Bridges Foreword by Richard Robinson New York • Toronto • London • Auckland • Sydney Mexico City • New Delhi • Hong Kong • Buenos Aires DEDICATION For all children, and for all who love and inspire them— a world of possible awaits in the pages of a book. And for our beloved friend, Walter Dean Myers (1937–2014), who related reading to life itself: “Once I began to read, I began to exist.” b Credit for Charles M. Blow (p. 40): From The New York Times, January 23 © 2014 The New York Times. All rights reserved. Used by permission and protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States. The printing, copying, redistribution, or retransmission of this Content without written permission is prohibited. Credit for Frank Bruni (p. 218): From The New York Times, May 13 © 2014 The New York Times. All rights reserved. Used by permission and protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States. The printing, copying, redistribution, or retransmission of this Content without written permission is prohibited. Scholastic grants teachers permission to photocopy the reproducible pages from this book for classroom use. No other part of this publication may be reproduced in whole or in part, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without permission of the publisher. For information regarding permission, write to Scholastic Inc., 557 Broadway, New York, NY 10012. Cover Designer: Charles Kreloff Editor: Lois Bridges Copy/Production Editor: Danny Miller Interior Designer: Sarah Morrow Compilation © 2014 Scholastic Inc. -

Ingham County News $1.00

••• —v^>'•^;^ie-•;^•>••ri:^.s;5^ . Tanto, tlie murderer of the family NOTHING OOINQ ON. Clothing.—L. C. Webb. Legal. at Delhi, wascaptured near the village kawirram Dry Fork Contributed t« m of OkemoB Monday evening, and Arkantaw Coontjr Vapor. NNUAL STATEMENT FOB THE YEAR ondlns December 31sl, A. 0.1888. of the would have been lynched only for the Rain. Acondition and aflalra ot tho Farmers'Mutual Biver rising. Fire Insurance Company, located at Mason, interference of tbeoffloera. 1-4 Off! 1-4 0ff!kp™ orEaniied under the laws of the State of Mich People are clearing up new ground, igan, and doing business In: the County of The chlldrens' concert, which was Ingham In said State. „ ., . Ihdefluately postponed in consequence kggs are scarce, but prospects are RICHARD J. BCLLKK, President. good. ORVit.t.K F. MtLi.ER, Secretary. CLUB ROOM, Jan. 28,1889. of the sickness of Mrs. Sturgi# daugh Postofflce Address of Secretary, Mason. Dan Boyd chopped off three of his TEN THOUSAND DOLLAR pi. Tber^ was a good attendance and ter, will be Riven at the M. E. church XEMBEr.8HIF8. ,ii V some new faces for this year. on Wednesday evening, Feb. 6. A toes with an axe day before yesterday. CASH SALE OF Number of members December 3lst, of prevtouH years 2,583 VOL. XXXI-NO. 6. • Secretary Ives absent. good program is expected, admission Uncle Billy Marsh has the thanks of Number of members added during MASON, MICH.. THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 7.1889. I Under the call "Market Reports," ten cents. The proceeds are to be the ye correspondent for a mess of squir^ the present year WHOLE NO. -

Andreas Gus Hansen CV

CV Andreas Gus Hansen Senast uppdaterad 2021-04-29 09:18 Personal data Age 33 Andreas G. Hansen CV Education Year School Education 2011 Nørgaards Højskole Film Acting 2011-2012 New York Film Academy Acting For Film & TV Stage Year Production Character/Role Prod. Company Director 2019 Idomeneo, Royal Danish Soldier Det Kongelige Teater Robert Carsen Opera Film/TV Production Character/Role Prod. Company Director Mistake (short film) Lars (supporting) Two Trick Pony Joe Withers Blot et Bånd (short film) Big Brother (lead) NEXT Marianna Bjørgheim The Investigation (TV series) Andreas (guest) Miso Film Tobias Lindholm The Sommerdahl Murders (TV Carl / P:H:A Assistent (guest) Sequoia Carsten Myllerup series) Shit Happens (short film) Lead Jesper Holm Pedersen KBH Film- og Fotoskole Dreaming in Mono (mini series) 'Mad' Mads Steen (supporting) Happy Fiction Jens Jonsson Sida 1/3 Ronnie Looks at the Stars Brian Odense Filmværksted Jesper Quistgaard (novel film) Video/Music video Production Artist Song Role New Land Lukas Graham Not A Damn Thing Changed Friend Karma Film Tina Dickow Fancy Hero David Fincher Justin Timerlake ft Jay-Z Suit and Tie Guy in casino Radical Media P!NK Blow Me (one last kiss) Hero Team Karate Dúné Victim Of The City Guy Commercial Production Character/Role Prod. Company Director Lego Adult LEGO Rasmus Mateus Collection Friend in group Belckout Josefin Malmén VVS Branchen VVS'er Entrance Film Tobias Kampmann Arla Jörd Hero Provocateur Meeto Kronborg Cocio Friend Hobby Film Martin Åkerhage Volvo Grandson Smuggler / Gatehouse Miles Jay NCAA Student Chelsea Productions Nadav Kander Spar Købmand Friend to Hero Another CPH Martin Høgsted Norwegian Airlines Traveling passenger Bacon Productions Miracle Whip Hero Parachute Productions Dan Monick Other Year Production Position Prod. -

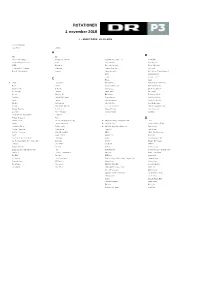

Rotation Master P3.Xlsx

ROTATIONER 1. november 2018 = ADDET SIDEN 24-10-2018 P3s Uundgåelige Jade Bird Uh Huh A B MØ Blur Phlake, Mercedes Waited All Summer Post Malone, Swae Lee Sunflower Troye Sivan, Charli XCX 1999 Zara Larsson Ruin My Life KOPS Salvation Dermot Kennedy Power Over Me 5 Seconds Of Summer Valentine Twenty One Pilots My Blood Bastille, Marshmello Happier Lukas Graham Not a Damn Thing Changed Benal Lampeskærm C Sigrid Sucker Punch Elisha Loyal Robyn Ever Again Karl William Høje strå (Dunhammer) Bette Darling Nephew, Nik & Jay Rejsekammerater Dominic Fike 3 Nights Alex Vargas Silent Treatment Nicklas Sahl Planets Dean Lewis Be Alright Halsey Without Me Barselona Fra Wien til Rom Ava Max Sweet But Psycho Grace Carter Why Her Not Me Khalid Better Elias Boussnina Candy [Radio Edit] Medina Væk mig nu Alice Merton Why So Serious Nosaint Nocturnal Delirium Silk City, Dua Lipa Electricity [Radio Edit] Maggie Rogers Give a Little Lukas Graham Love Someone L Devine Peer Pressure Ariana Grande breathin Christine And The Queens 5 dollars Thøger Dixgaard Pæn D Selma Judith Kind of Lonely [Radio Edit] Kendrick Lamar, Anderson .Paak Tints Jungle Heavy, California Little Dragon Lover Chanting [Edit] Alexander Oscar Coffee Table Ellie Goulding, Diplo, Swae Lee Close to Me Scarlet Pleasure Superpower Freja Kirk Fine Things Artifact Collective Ways [Radio Edit] HRVY I Wish You Were Here Yulez Major Friend Kwamie Liv New Boo Calvin Harris, Sam Smith Promises Aisle Favorite Bad Habit Au/Ra, Alan Walker, Tomine Harket Darkside IVYxM Slippin' On Trouble Jamaika Abu Debe RoseGold Selena Imagine Dragons Natural Askling So Precious Bugzy Malone, Rag'n'Bone Man Run Communions Is This How Love Should Feel? The 1975 Love It If We Made It NAO, SiR Make It Out Alive Ray BLK Run Run ROSALÍA Malamente St. -

Paseo Post Intercambios Paseo

F E B R E R O 2 0 1 9 | N º 2 PASEO POST INTERCAMBIOS PASEO PRIMARIA SE ESTRENA EN PASEOPOST LA EDUCACIÓN NO ES CAPACITAR PERSONAS PARA LA EMPRESA , SINO FORMAR PERSONAS Foto de :http://audioforo.com/2017/10/08/la-educacion-en-espana/ Foto de: https://conscientemente.net/escribir-hace-bien-la-escritura-como-practica-meditativa-y-terapeutica/ E N S A L E S I A N O S P A S E O INTERCAMBIOS PASEO A r i a d n a C a l v o e I r e n e C i s n e r o s | E d i t a d o p o r : Carmen Silva Al comienzo de este curso, alumnos de tercero y cuarto de la E.S.O, y también primero y segundo de bachillerato, tuvieron la oportunidad de experimentar un intercambio escolar con alumnos extranjeros. Los alumnos de tercero, viajaron hasta un colegio situado en Ruan, una ciudad del noroeste de Francia. Meses después, alumnos franceses asistieron a nuestro colegio durante unos días. Todos coinciden en que fue una gran experiencia y la volverían a repetir. Los alumnos de bachillerato estuvieron en un colegio de Boston. Boston, es la capital del Estado de Massachusetts, y una de las ciudades más antiguas de los Estados Unidos.Las familias de estos alumnos, acogieron después a los estudiantes norteamericanos, para completar el intercambio. Un colegio de Dublín, próximo al mar, ha sido el destino de los estudiantes de cuarto de la E.S.O. ''Para mí, el intercambio con Irlanda ha sido una manera de aprender otra cultura y conocer cómo es estudiar en ese país, ya que cuando vas de turismo es algo que no sueles ver. -

Repor T Resumes

REPOR TRESUMES ED 017 400 RE 000 985 GUIDE FOR REMEDIAL READING IN THE ELEMENTARYSCHOOL, GRADES TWO THROUGH EIGHT. BY- SLICK, ELINOR AND OTHERS EVANSVILLEVANDERBURGH SCHOOL CORP., IND. PUB DATE EDRS PRICE MF -$0.50 HC -$4.16 102P. DESCRIPTORS- *CURRICULUM GUIDES, *REMEDIAL READING,*READING MATERIAL SELECTION, READING DIAGNOSIS, ELEMENTARY GRADES, JUNk)R HIGH SCHOOLS, AUDIOVISUAL AIDS, ORAL READING,READING COMPREHENSION, WORD RECOGNITION, DIAGNOSTIC TESTS,VOCABULARY DEVELOPMENT, THE REMEDIAL READING PROGRAM OF THE EVANSVILLEVANDERBURGH SCHOOL CORPORATION IS CONCERNED WITH INDIVIDUAL STUDENTS WHOSE READING LEVEL INDICATESA DISCREPANCY BETWEEN PERFORMANCE AND CAPACITY FORLEARNING. THE GUIDE WAS DESIGNED FOR USE IN GRADES 2THROUGH 8 AND IS DIVIDED INTO THREE AREAS -- (I) DIAGNOSIS, INCLUDING SELECTED INTELLIGENCE TESTS, SELECTED READING TESTS, AND USEOF REPORTING OF RESULTS? (11) MATERIALS AND FACILITIES, INCLUDING AUDIOVISUAL AIDS, AND (III) TECHNIQUESFOR TEACHING VOCABULARY, INCREASING COMPREHENSION, IMPROVING ORALREADING ABILITIES, AND MOTIVATING RECREATIONAL READING.AN ANECDOTAL RECORD, A WEEKLY PLAN SHEET, AND A YEAR -ENDCHECK SHEET ARE SUGGESTED AS AIDS. A BIBLIOGRAPHY OFPROFESSIONAL BOOKS AS WELL AS BOOKS FOR CHILDREN IN GRADES 1 THROUGH 6ARE INCLUDED. THE APPENDIX CONTAINS VARIOUS DATAAND INFORMATIONAL SHEETS. (JM) 5a U.S. DEPARTMENTOFFICE OF HEALTH, OF EDUCATIONEDUCATION & WELFARE I THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCEDEXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSONSTATEDPOSITION DO OR OR NOT ORGANIZATION POLICY. NECESSARILY ORIGINATING REPRESENTIT.OFFICIALPOINTS OFFICE OF VIEW OF EDUCATION OR OPINIONS GUIDEfor fi ELEMENTARYREMEDIALin the READING SCHOOL GRADESTwo throughEIGHT eLtcg,Ee.,hvoife. EVANSVILLE-VANDERBURGHEVANSVILLE, SCHOOL INDIANA CORPORATION GUIDEfor ELEMENTARYREMEDIALin theREADING SCHOOL Produced by CommitteesSchool Year of1966-1967 Teachers During the THE BOARD OF SCHOOL TRUSTEES Mr.Dr. AlbertWilliamC.Vice-President K.Mr. -

Nov Dec 2018

1 HD – NOV. & DEC. 2018 Mumford and FFFIIILLLEEE TTTIIITTTLLLEEE AAARRRTTTIIIISSSTTT Slaves FFFIIILLLEEE TTTIIITTTLLLEEE 16754 Chokehold 16772 I Gave You All Sons New Songs 16852 Christmas Bonus Aegis 16879 If You See Her Lany Charli XCX feat. Children's Gary 16822 1999 Troye Sivan 16755 Climb Climb Sunshine Mountain Song 16958 Ikaw Lamang Valenciano Ellie Goulding ft. 16736 8 Letters Why Don't We 16853 Close To Me Diplo and Swae L 16880 I'll Never Love Again Lady Gaga 16737 A Little Love Goes A Long Way Do Re Mi 16756 Clueless Sam Mangubat 16881 I'm Still Here Sia Children's David Mariah Carey 16823 A No No 16854 Come Follow Me Song 16773 In Our Hands Pomeranz Children's GMA Christmas Michael Bolton 16824 A Peanut Sat Song 16855 Completely 16882 Ipadama Ang Puso Ng Pasko Station ID Children's Sarah Camila Cabello 16825 A Sailor Went To Sea Song 16856 Consequences 16774 Isa Pang araw Geronimo Hans St Paul and The Jex De Castro 16826 Ako Ako Dimayuga 16757 Convex Broken Bones 16883 Isang Gabing Pag-ibig Kry stal Brimner & 16827 Alibi Bradley Cooper 16858 Dalawang Pag-ibig Nya Sheena Belar 16775 Isang Pangako Ato Arman 16739 All Day Long Garth Brooks 16860 Di Makatulog SUD 16776 It's All Over Now Rod Stewart Children's Janine Tenoso Sheena Easton 16828 Ally Bally Bee Song 16862 'Di Na Muli 16884 It's Christmas Al Over The World Rod Stewart ft Children's Ladi Gaga 16829 Always Remember Us This Way 16758 Didn't I Bridget Cady 16878 I've Got The Joy Joy Joy Song Children's Lady Gaga, Children's 16741 Angels Watching Over Me Song 16863 Diggin' My Grave Bradley Cooper 16885 Jelly On A Plate Song Nick Jonas feat. -

Janet and John: Here We Go Free

FREE JANET AND JOHN: HERE WE GO PDF Mabel O'Donnell,Rona Munro | 40 pages | 03 Sep 2007 | Summersdale Publishers | 9781840246131 | English | Chichester, United Kingdom Janet and John Series by Mabel O'Donnell Unfortunately we are currently unable to provide combined shipping rates. It has a LDPE 04 logo on it, which means that it can be recycled with other soft plastic such as carrier bags. We encourage you to recycle the packaging from your World of Books purchase. If ordering within the UK please allow the maximum 10 business days before Janet and John: Here We Go us with regards to delivery, once this has passed please get in touch with us so that we can help you. We are committed to ensuring each customer is entirely satisfied with their puchase and our service. If you have any issues or concerns please contact our customer service team and they will be more than happy to help. World of Books Ltd was founded inrecycling books sold to us through charities either directly or indirectly. We offer great value books on a wide range of subjects and we have grown steadily to become one of the UK's leading retailers of second-hand books. We now ship over two million orders each year to satisfied customers throughout the world and take great pride in our prompt delivery, first class customer service and excellent feedback. While we do our best to provide good quality books for you to read, there is no escaping the fact that it has been owned and read by someone else before you.